Current Urban Studies

Vol.03 No.02(2015), Article ID:57612,13 pages

10.4236/cus.2015.32013

Urban Governance in the Changing Economic and Political Landscapes: A Comparative Analysis of Major Urban Centres of Tanzania

John Modestus Lupala

School of Urban and Regional Planning, Ardhi University, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania

Email: lupalajohn@yahoo.com

Copyright © 2015 by author and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 1 June 2015; accepted 26 June 2015; published 30 June 2015

ABSTRACT

Urban development in many cities of the developing world has been facing innumerable challenges some of which are historical but others attributed to governance. While the changing socio- economic and political landscapes have been shaping the pattern of urban governance in these cities, studies underscoring the link between central, local governments and the citizenry are scanty. This paper attempts to analyze urban governance in the Tanzanian context drawing empirical evidence and lessons from eight major urban centres of Tanzania. This paper is a product of the study that was carried out to examine the state of cities in eight (8) major urban centres of Tanzania between 2010 and 2013. It attempts to compare governance issues and develop some indices across major urban centres of Tanzania. The data collection methods included household interviews, review of official records, workshops, group discussion and reports from city coordinators. The results show that: although Tanzania has made some strides towards effective urban governance, the level of achievement varied from one city to another. Poor performance was noted on parameters of continued centralization of power by the central government, continued financial dependency on central government, limited participation and civic engagement of local communities in development projects and political undertakings. As a way forward it has been recommended that there is an urgent need to re-orient the on-going local government reform programmes to ensure that true decentralised functions, powers and mandates are exercised from below. This should be accompanied with capacity building to ensure effective participation of key stakeholders.

Keywords:

Urban Governance, Economic and Political Landscapes, Urban Centres, Tanzania

1. Introduction

One of the obvious reasons for improved urban governance in cities of the developing world is the changing context within which local governments operates that has become much broader and more complex. While many countries worldwide have adopted political, social and economic reforms; the important elements in the development process have been lacking including the connection between the central and local governments and their link to emerging structures of civil society (McCarney, 1996) . The debate over the need for good urban governance has increasingly gained importance focusing on issues of decentralisation, accountability, economic growth and development. It has gained more importance when linked to initiatives for poverty alleviation. On the basis of this background, the UN-Habitat launched the Global Campaign on Urban Governance in 1999. The campaign’s goal was to enhance the quality of life in cities as well as to contribute to the eradication of poverty through improved urban governance (Taylor, 2000) . The campaign categorically stated that the quality of urban governance is the single most important factor for the eradication of urban poverty and for prosperous cities. It aimed at increasing the capacity of local governments and other stakeholders to practice good urban governance. There have been debates on how to delegate functions and powers from the central government to the local government. The issue of how bottom-up approaches in planning and implementation can be promoted; and how grassroots communities can be empowered to take the lead in urban development agenda constitute the key elements of good urban governance. The changing macro and micro political and economic landscapes in these countries have created new demands on how cities can be well managed. These changes have been manifest in terms of adoption of multiparty from single party partisan political systems, adoption of liberal policies whereby increasingly, the private sector is contributing to national economic ventures including employment, deregulation of fiscal policies and prices, increased freedom of speech and election of political leaders. The rationale for improved governance therefore becomes a central point of discussion and more so, in urban settings where dynamics of change and transformation are more apparent in the last three decades.

2. Conceptualizing Urban Governance

Governance as a concept has been debated from various perspectives and contexts. Generally, governance refers to integrated mechanisms, processes and institutions, through which citizens and social groups state their preferences and negotiate their differences. They also use their constitutional rights to realize their duties (Banachowicz & Danielewicz, 2004 in Jusoh & Rashid, 2008) . Thus, public governance should guarantee that in formulating and implementing political, social and economic priorities and decisions that influence resources and goods allocation, social consensus, with both the poorest and the richest affairs are taken into account. Urban governance is therefore a sum of the many ways individuals and institutions, public and private, plan and manage the common affairs of the city. It is a continuing process through which conflicting or diverse interests may be accommodated and cooperative action can be taken. It refers to how a city community organises itself, determines its priorities, allocates resources, selects who has a voice and holds each other to account (South African Cities Network, 2006; UN-habitat, 2010) .

Cheema (1997) defines governance as: “The exercise of political, economic and administrative authority to manage a nation’s affair. It is the complex mechanisms, processes, relationships and institutions through which citizens and groups articulates their interests, exercise their rights and obligations and mediate their differences”. Cheema argues that sound governance is notable where public resources and problems are managed effectively, efficiently and in response to critical needs of society. Good urban governance is generally understood to include variables such as: welfare of the citizenry; enabling women and men to access the benefits of urban citizenship and upholding the principle that no person can be denied access to the necessities of urban life, including adequate shelter, security of tenure, safe water, sanitation, a clean environment, education and nutrition, employment, public safety and mobility. Accordingly, urban governance can also be viewed as “the relationship between civil society and the state, between rulers and ruled, the government and the governed” (McCarney, 1996; Lange, 2009). Cheema (1997) points out to four key variables that constitute governance namely; economic, political, administrative and systemic (Figure 1).

While economic governance refers to processes of decision making that directly affect countries’ economic activities or its relationship with other economies, administrative governance is a system of policy implementation carried out through an efficient, independent, countable and open public sector (Cheema, 1997) . Cheema further observes that economic governance has a major influence on societal issues such as equity, poverty and

Figure 1. Governance variables.

quality of life. On the other hand political governance refers to decision making and policy implementation of a legitimate and authoritative state. The state should consist of separate legislative, executive and judicial branches, represent the interest of the pluralist polity and allow citizens to freely elect their representatives (ibid.). The fourth variable of governance is systemic governance. This refers to the processes and structures of society that guide political and socio-economic relationships to protect cultural and religious beliefs and values and create and maintain an environment of health, freedom, security and with the opportunity to exercise personal capabilities that lead to better life for all people. The impetus of this paper is to examine the extent to which these key variables of governance have been operationalized in major urban centres of Tanzania.

Emerging from the foregoing arguments, urban governance as a concept entails several variables that might pose some difficulties in operationalizing in a study context. It was therefore important to develop specific themes that underpin governance in the Tanzanian city context. Thematically, the operationalization of governance concept in this paper was structured as follows: Economically; governance was examined in terms of extent of fiscal independence of cities and municipalities as compared to budgetary allocations from the central government, financing of priority projects and the proportion of municipal debt as compared to actual revenue. Politically; governance was viewed from democratic processes each municipality or city was exercising especially the aspect of conducting statutory meetings as part of participatory mechanisms in decision making and civic engagement especially in election of political leaders. Administratively; governance was examined in terms of decentralization, partnerships in service provision, transparency and accountability and promotion of bottom-up approaches focusing on implementation of projects that have been formulated by communities. Systemic governance embraced aspects of modernization of municipal administration for improved decision making, improvement of skills for the workers, efficiency and service delivery and the whole question of making land available for urban development (Figure 2).

3. Changing Economic and Political Landscapes of Tanzania

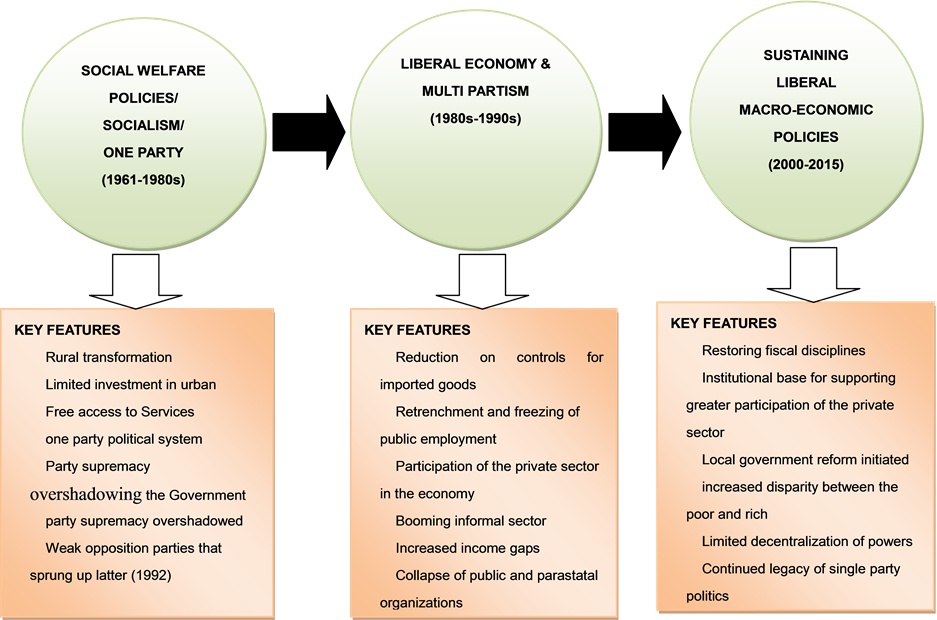

Tanzania has gone through three distinct phases of macroeconomic and political changes since independence (1961). These changes have had significant impacts on urban governance and overall development of the country. Immediately after independence, in 1961, Tanzania started to implement the social welfare policies or socialism as its macroeconomic policy framework that emphasized equity among its people (1961-1984) (Figure 3). Access to livelihood opportunities and basic services underpinned the principles of socialism. Advocacy on communal way of living and social welfare were emphasized (Lupala, 2014; Ngware et al., 2003) . More emphasis was put on rural transformation because people in the rural areas were relatively poor as compared to urban residents. All citizens were assured of free access to health, education and utilities especially water supply despite the fact that the Government had limited financial and human resource capacities. Several programmes were developed and implemented towards achieving this goal including the Universal Primary Education (UPE of 1974), and the Villagization Programme (1968-1976). The latter was meant to bring scattered rural homesteads to nucleated village settlements to facilitate provision of basic services such as health, education and potable water. Although substantial strides were made that depicted a larger dimension of service provision, this policy orientation could not be sustained because of poor economic performance amidst rapidly urbanizing

Figure 2. Contextualizing variables of urban governance.

Figure 3. Changing economic and political landscape of Tanzania.

cities. Politically, the government was operating under a one party political system that was declared three years after Independence. The party supremacy overshadowed the role of the government and political leaders were more powerful than the government leaders. Yet, even though the party did clearly become authoritarian, the people never suffered any overt repression that was observed in some other African dictatorships. The legacy of single party state is notable in the feeble and unconvincing opposition parties that sprung up after the change of constitution and introduction of multi-party democracy in 1992.

The second socio-economic and political epoch is a period between 1985 and 1995 that observed a shift from controlled and planned to market oriented or liberal economy and multi party political system. It was during this period that the Structural Adjustment Programme (SAP) was implemented. This was characterized by among other changes; reduction on controls for imported goods, retrenchment of public employees and freezing of public employment (Ngware et al., 2003) . The private sector participation in the national economy increased. As consequence of retrenchment of public employees, the informal sector grew rapidly depicted by the increase in informal sector street trading and rapid expansion of informal settlements. It was during this phase that increased income gaps started to emerge and most of the public and parastatal organizations collapsed. In the urban setting, the unprecedented urban growth and increasing poverty resulted into socio-spatial disparities between and within cities. This was manifest in the growing gap between the privileged enclaves of middle and high income and the largely un-serviced informal settlements of the urban poor. It was also during this phase (1992) that multiparty politics was allowed to operate. Until 1992, only three political parties were operating. This number grew to 22 parties in 2014.

The third phase started from 1995 to the present times (2015). The focus has been on sustaining liberal macro-economic policies, restoring fiscal disciplines and creating an institutional base for supporting greater participation of the private sector. It was during this phase that the local government reform programme was initiated with a view to decentralizing powers and resources to local governments (Lupala, 2014; Ngware et al., 2003) . Although policy reforms in this period focused on sustaining achievements made through the second phase, the disparity between the poor and affluent people is on the increase. The centralization of powers particularly financial resources has left most of the urban local authorities largely dependent on the central government for even budgetary allocations for recurrent expenditures. Not much has been sustained in terms of decentralization by devolution (D by D) despite a relatively longer period of implementing the local government reform programme. Politically, the legacy of single party politics is still haunting true democratic processes. Only a few political parties have grown to the extent of challenging the ruling party. This is perhaps one of the the main challenges the government is currently facing to ensure that there is effective decentralization of powers and resources to enable urban local authorities implement planned programmes and projects and true democratic processes for urban governance. Important questions that are worth examining are; to what extent urban local authorities have been facilitated to effectively provide urban governance to their local populations? What has been the implication of the changing economic and political landscapes to urban governance and city sustainability in Tanzania?

4. Methods

This paper is one of the outputs of the study project of the “Tanzanian State of the Cities Project” (2010-2013) that was carried out in eight (8) major urban centres of Tanzania between 2010 and 2013. The project focussed on examining five key thematic areas of governance, sustainability, safety and security, productivity and inclusiveness. Both static and trend data were collected on these five thematic areas. The study was conducted in the cities of Dar es Salaam (that comprised the three municipalities of Ilala, Temeke and Kinondoni whereby each municipality was treated as an independent case), Mwanza, Tanga, Arusha and Mbeya and the Municipality of Zanzibar. Participatory data collection method was employed whereby each urban centre established a team that was responsible for collecting data on each thematic area. At the beginning of the project data collection tools and indicators for each thematic area were agreed upon by all teams in a workshop that was organized in Dar es Salaam. Each team developed a sample size based on 95 percent confidence. The sample sizes were established based on number of houses in each city from where household interviews were conducted. The estimation on number of houses was based on house count in each urban centre from latest aerial photos of 2010. This exercise culminated in sample sizes of 399 houses for IIala, 287 for Temeke, 399 for Kinondoni, 398 for Mwanza, 440 for Tanga, 278 for Arusha, 397 for Mbeya and 395 for Zanzibar Municipality. Household interviews were conducted in each city by interviewing heads of households (more specifically house owners) for household data. Since this was a large survey done at city level only 15 questions were asked and the timing of each house could last from fifteen to thirty minutes. Household surveys were complemented with spatial data sources from city specific aerial photos, satellite images and existing maps and plans. Official data (reports and documents) were collected from relevant offices spanning for the period of five years (between 2007 and 2012). At data analysis stage, comparison across cities was done using spreadsheet, tables and graphs.

5. Results

5.1. Fiscal Independence of Urban Local Authorities

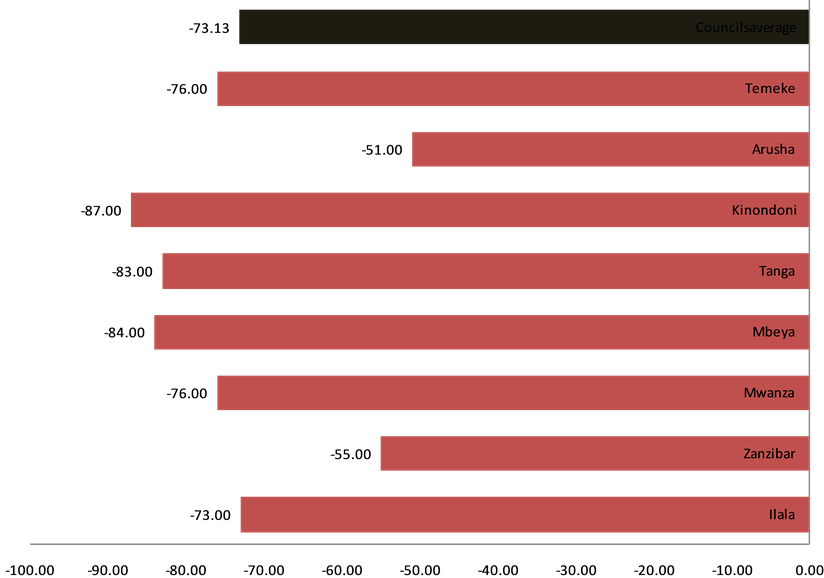

Although one of the criteria for urban settlements to attain the status of a municipality is to collect 70 per cent or above of their revenue from their own sources, the majority of cities and municipalities in Tanzania were still dependent on central government financing. They were dependent for development projects, personnel emoluments and recurrent expenditures. Evidence from field results indicated that on average, the proportion of funds received from the central government in relation to the total budget of a urban local authorities stood at 73.13 per cent (Figure 4). The negative sign denoted dependence. Kinondoni was leading with a total dependence of 87 percent followed by Mbeya that was dependent by 84 percent. The least dependent were arusha and Zanzibar that registered dependence ratios of 51 and 55 percent respectively. The dependence on central government financing not only undermined the primary objectives of decentralization by devolution but also incapacitated cities and municipalities in reaching their maturity in terms of financial sustainability. Overdependence on central government financing undermined the whole idea of enabling cities and municipalities autonomous and the overall goal of good urban governance. In this aspect, one could say that the Tanzania’s experiment of decentralization has proved failure in terms of fiscal independence.

5.2. Financing of Priority Projects

Each urban authority was required to set aside funds for priority projects annually. The underlying assumption for allocative efficiency was to strive to fund key priority areas or projects as stipulated by each municipality or city. Most cities and municipalities were faring well under this sub-component. Except for Zanzibar, where none of its priorities were funded, the average funding of budgetary priorities for the other cities and municipalities stood at 82 per cent. Mwanza and Ilala were the only cities that reached allocative efficiency by funding 100 per cent of their prioritised projects.

Figure 4. Fiscal independence of city councils (%) (2008-2011).

5.3. Municipal Debt

Debt size and capacity to service debt are two key variables of financial stability of many urban local authorities in Tanzania. In absence of policy provisions and guidelines on capacity and ceiling on debts to be serviced by urban local authorities, the debt size has been determined by the minister responsible for local government. The factors that were used in determining the ceiling for debt included the capacity of municipalities to generate their own revenue and their available assets including land. There was, however, no fixed ceiling on debt size. In the context of this paper, analysis was centred on the proportion of municipal debt to own sources revenue. The aim was to determine the capacity of cities and municipalities to service debts as an indicator of financial stability. Evidence from cities and municipalities indicated that there was wide a variation on the ratio of debt to revenue, with an average of 27 per cent across cities and municipalities. Zanzibar, for example, had the highest debt- revenue ratio of 66.1 per cent followed by Temeke with 44.7 per cent and Tanga that had 31.9 per cent. Other urban areas revealed relatively lower debt-revenue ratios, as summarised in Table 1.

In addition to the ratio on debt-revenue, the trend on growth of debt in the period 2007-2011 was analysed to explore the temporal pattern in financial stability across cities and municipalities. Except for Mwanza, where the size of debt remained constant, other cities revealed increasing debt over time. Rapid growth in debt size was recorded in Temeke Municipality. In Temeke, the debt size increased from Tanzanian Shillings 1.76 billion in 2009 to Tanzanian Shillings 8.2 billion between 2009 and 2011. This represented an increase of 366 per cent. The debt increase was due to a loan that was advanced to Temeke for land acquisition. This was followed by Kinondoni, with a growth of 133 per cent in the same period. Although increase in debt size and rate indicated the potential for borrowing, the rapid increase equally jeopardised financial stability of cities and municipalities.

5.4. Democratic Processes in Urban Councils

One of the objectives of good urban governance is to improve transparency and accountability. Council and Committees meeting have been considered as forums through which transparency and democratic decision making processes could be articulated. Cities and municipalities were receiving guidelines from the responsible ministry on the minimum number of statutory meeting to convene. For example, the requirement for the Finance and Administration Committee was to meet monthly. The Full Council and other Committees had to meet quarterly. In the Finance and Administration Committee, financial and administration matters were usually discussed and deliberated upon and subsequently submitted to the Full Council for approval. Being the representative of people, the Full Council (mostly constituted by democratically elected councillors) was the crucial meeting that was making various decisions; to make the proceedings more transparent, ordinary citizens were also invited to attend. However, excessive council meetings may also be a sign of inefficiency in decision-making that may culminate in misuse of public resources.

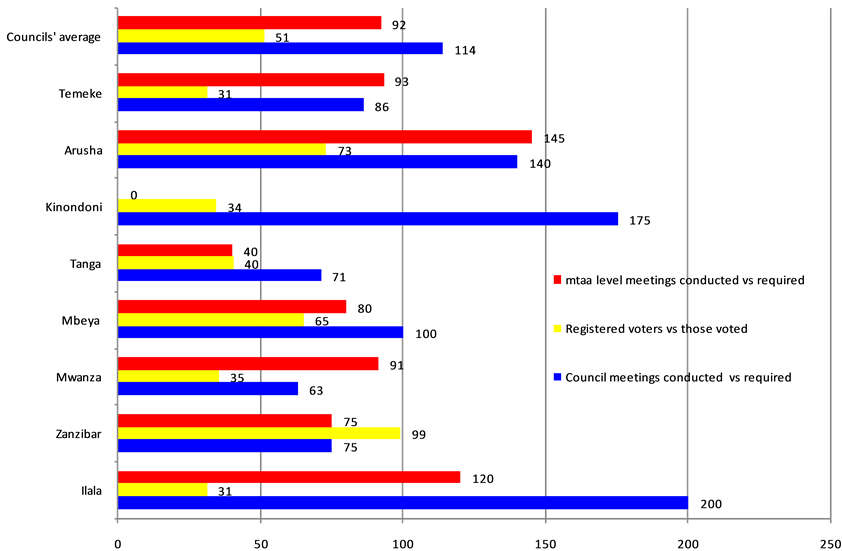

The state of intra-council political efficacy as indicated by adherence to required meetings showed a varying pattern across cities and municipalities. Empirical evidence showed that half of the councils exceeded the required number of meetings and the other half had less meetings than required. For example, while Ilala Munici-

Table 1. Revenue-debt ratio (2011).

Source: Official records from municipal and city treasurers’ offices (2012).

pality held double the required number of council meetings, Mwanza City Council conducted 63 per cent of the required meetings, or approximately two full council meetings or seven finance and administration meetings. Variations across cities and municipalities were reported to be as follows: Zanzibar 75 per cent, Mbeya 100 per cent, Tanga 71 per cent, Kinondoni 175 per cent, Arusha 140 per cent and Temeke 86 per cent. Implicitly, the lesser the number of meetings indicated limited transparency and accountability to the people (Figure 5).

The rapid changes that were taking place in most of cities and municipalities necessitate local authorities to enact as many by-laws to cope with the changes. Evidence showed that many city and municipal councils prepared by-laws satisfactorily. For example, in the year 2011, the cities of Mbeya and Arusha enacted and approved 8 by-laws each, followed by Mwanza and Temeke, which enacted 5 and 4 by-laws, respectively. Zanzibar enacted only 3 by-laws and Kinondoni enacted only 1 by-law. By-laws as tools for enforcing specific issues in cities and municipalities have proved to be useful, especially in achieving environmental cleanliness and revenue collection. Mbeya and Arusha were not performing well in environmental cleanliness, and therefore, enacted many by-laws that were linked to city strategies to improve performance in this area.

5.5. Civic Engagement in the Election of Leaders

Tanzania adopted multiparty democracy from 1992 as part of the political reforms that swept Africa and the rest of the world. This shifted the dominance of the one-party system to numerous political parties with varying ideologies. It also widened the freedom of people to elect their leaders. The Local Government Reform Agenda (1996) requires the leadership of local authorities to be chosen through a fully democratic process. In exploring response rate of political participation in electing leaders, the analysis focused on the proportion of registered voters as compared to those who turned up for voting. Findings from the eight cities and municipalities revealed that, on average, 51 per cent of the registered voters participated in the exercise. The response rate was highest in Zanzibar Municipality where 99 per cent of the registered voters participated in elections. This was followed by the Arusha and Mbeya where 73 and 65 per cent of registered voters voted, respectively. The remaining urban centres registered less that 40 per cent, as shown in Figure 5. The overall results for this variable indicate low levels of civic engagement in political participation, especially in electing leaders. This indicates the need for investing in civic awareness campaigns to make citizens more engaged in electing leaders who represent their interests.

Figure 5. Meetings and voter turnout.

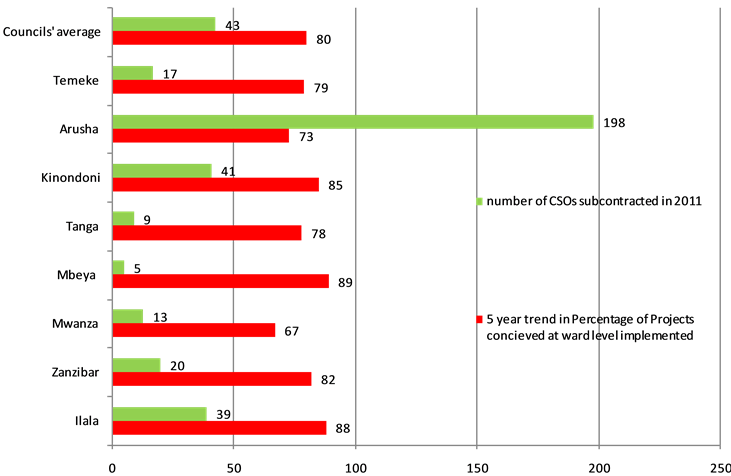

5.6. Decentralization and Partnership in Service Provision

Decentralisation as a variable of urban governance also entails issues related to public-private partnership in service provision. The Tanzania Public Private Partnership Policy (PPP) (URT, 2009) and the Local Government Reform Programme (2009) (PMO-RALG, 2009) advocate the promotion of private sector participation in the provision of resources. This partnership may be in terms of investment capital, managerial skills and technology (ibid.). Partnership in this project was analysed based on the number of Civil Society Organizations (CSOs) that were partnering with urban local government authorities. Empirical evidence across the eight urban centres indicated wide variations in the level of involvement of CSOs and use of public-community partnerships. For example, while Arusha recorded a total of 198 cases of PPP, Mbeya had the lowest with only 5 CSOs that were participating. Other cities and municipalities had the following pattern; Ilala (39), Zanzibar (20), Mwanza (13), Tanga (9), Kinondoni (41) and Temeke (17). Questionably, there was no correlation between the number of participating CSOs and the level of services provided. For example, while Tanga had lower number of CSOs partnering with the local authority to provide services (9), it was doing better in terms of solid waste management than Arusha, which had the highest cases of CSOs in PPP (198) (Figure 6). This suggests that it is not the number of CSOs that was participating in PPP that determined the level of service delivery, rather, other variables such as capacity, efficiency and facilitation from the local authorities.

5.7. Transparency and Accountability

Peoples’ awareness on development projects at Mtaa level was considered as one of the indicators of transparency. Current guidelines require that Mtaa and Village meetings are conducted quarterly. The underlying aim of Village and Mtaa meetings was to get people involved in planning and implementation of development projects at grassroots level. At city and municipal level, the gauging factor wss the number of meetings convened as compared to the statutorily required meetings. Overall results from the eight cities and municipalities showed a satisfactory performance level of 92 per cent. However, there was variation across cities and municipalities, with the highest frequency reported in Arusha (145 per cent) followed by Ilala (120 per cent), Temeke Municipality (93 per cent), Mwanza (91 per cent), Mbeya (80 per cent), Zanzibar (75 per cent) and Tanga (40 per cent). At household level, people’s awareness of development projects was relatively low, with an average of 47 per cent across all cities. However, there were big variation among cities; Arusha recorded very low awareness (9 per cent), while in Ilala registered 86 per cent. The figures for the other urban areas were as follows: Zanzibar 44 per cent, Mwanza 17 per cent, Mbeya 61 per cent, Tanga 23 per cent, Kinondoni 67 per cent and Temeke 68 per cent.

Figure 6. Number of partnerships with CSOs and projects implemented.

5.8. Promoting Bottom-Up Approaches

Promoting bottom-up approaches constituted one of the variables of good urban governance. Contextually, the Local Government Authority performance measure requires that at least two wards implement planning from below employing the Opportunities and Obstacles for Development (O & OD) methodology. This measure was also stated even in the Local Government Reform Programme Phase II (LGRP II) in 2009 (PMO-RALG, 2009) . It aimed at Local Government Authorities to derive their legitimacy from services provided to the people (LGRP II, 2009). It also aimed at fostering participatory development and building institutions that reflected local demands and conditions. Examining cities’ response in implementing projects from below, results showed that cities were performing well in responding to proposals and plans from lower levels of local government. On average, 80 per cent of plans/projects implemented were planned from lower levels; at wards and sub-wards. However, there were variations across cities and municipalities. While Mbeya recorded the highest average of 89 per cent, the lowest was recorded in Mwanza that had only 67 per cent (Table 2).

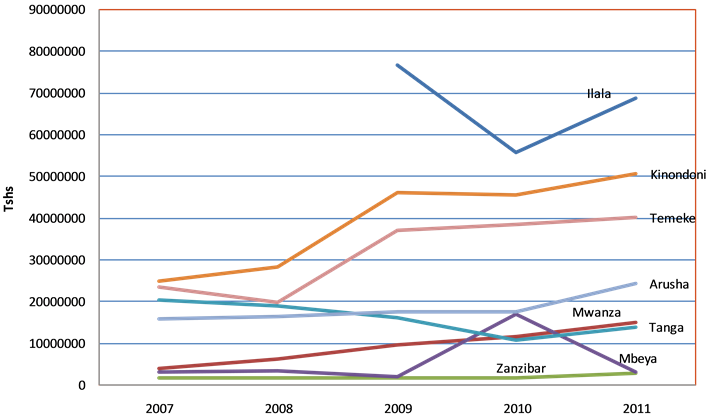

In terms of trends in disbursement of funds, a steady trend was observed in the municipalities of Kinondoni, Temeke and Arusha. Other cities and municipalities had either constant or fluctuating patterns of funds disbursed to ward levels as indicated in Figure 7.

5.9. Improving Efficiency through Modernisation of Municipal Administration

Modernisation of municipal administration focused on exploring whether municipal departments had automated

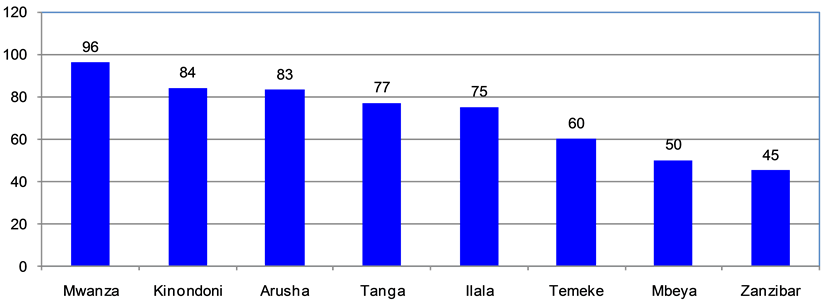

Table 2. Projects implemented through bottom-up approaches.

Source: Official records from municipal and city treasurers’ offices (2012)

Figure 7. Trends in disbursement of municipal funds to Ward levels.

software, the state of office accommodation within municipal departments, and whether cities and municipalities had well-established training policies or programmes. Use and application of Information and Communication Technology (ICT) in municipal management constituted one of the key elements of the local government reform programme. The Local Government Reform Programme (2009) provided for every urban local authority to apply information and communication technology (ICT) to improve efficiency and effectiveness in service delivery from 2011. A specific output under this target was to install EPICOR or its replacement software for improved financial management and accountability (PMO-RALG, 2009) . Across the eight municipalities and cities, inventory on availability of 12 key software packages was made. These included: LAWSON, EPICOR, MTEF/ PLANREP, LGMD, GHRIS, By law Database, GIS, TMIS, TOMSHA, MTUHA, MRECOM and MOLIS. The general picture that emerged from this sub-component indicated average performance. About 71 per cent of all cities and municipalities had these software in place. One of the common software was EPICOR which was connected through the National ICT Broadband Backbone Network. However, there was a big variation among the Local Government Authorities whereby Zanzibar and Mbeya were found to be lower as compared to Mwanza and Kinondoni. It was found that 96 per cent of city operations in Mwanza were being done using ICT while in Kinondoni it was 84 per cent (Figure 8).

In terms of staff training, evidence showed that there was a big variation across cities and municipalities. For example, while Kinondoni provided training to over 50 per cent of its staff, Zanzibar, Mbeya and Ilala had trained below 5 per cent of their staff.

5.10. Skills Requirement versus Availability

An assessment of institutional human resources revealed that most of the cities and municipalities seemed to suffer in this area as indicated by skill gaps. The skill gap was generally wide in Zanzibar with a 70 per cent gap of the required staff. The situation was relatively better in Kinondoni with a gap of only 5 per cent. The situation in other cities was relatively similar as follows: 37 per cent gap in Ilala, 37 per cent in Mbeya, 32 per cent in Tanga, 36 per cent in Arusha and 13 per cent in Mwanza. It was on the basis of this deficit that the second sub-component of the Local Government Reform Programme (2009) envisaged organization and human resource development at the local government level. Strategically, the programme targeted at deployment of staff to peripheral and disadvantaged urban centres with a view of filling in these gaps by 2014.

5.11. Making Land Available for Urban Development

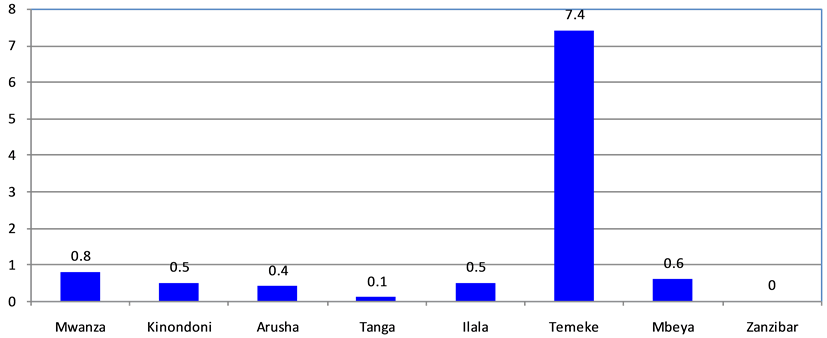

One of the indicators of good urban governance that was also taken into consideration was making land available for urban development. National policies require that cities and municipalities acquire land for public use and as a key component for allocative efficiency of land resources (URT, 1996; URT, 2007; URT, 1999; URT 2000) . Making serviced land available to all groups, including the urban poor based on the principle of cost recovery underpins the concept of allocative efficiency. In implementing these policy directives, municipalities and cities were acquiring land and paying compensation prior to selling it to prospective applicants. In total over 10 billion Tanzanian Shillings (approximately 5 million US $) had been already spent by all cities and municipalities for this purpose in the year 2011. There were, however, variations among cities. While Temeke spent

Figure 8. Application of ICT in municipal administration.

Tanzanian Shillings 7.4 billion, Mwanza spent Tanzanian Shillings 0.8 billion for land acquisition. Other municipalities had spent a relatively lesser amounts (Figure 9).

6. Discussion

Although indices for urban governance vary from one context to the other and from one country to another, for the purpose of this paper, thirteen variables were developed and deployed to examine and compare performance in governance across the eight major urban centres of Tanzania (Table 3). When cities and municipalities were compared on the basis of these variables Arusha city performed well and was ranked first with aggregated points amounting to 919.6 across these indicators. Impliedly, one can argue that in terms of governance, Arusha could be viewed as the well governed city in Tanzania followed by Ilala Municipality with a total points amounting to 849. Arusha was performing well because it exhibited the highest number of project partnerships with CSOs, highest number of meetings at council and sub-ward levels and modernization of city operations as compared to other cities (Table 3). Ilala was doing better in the aspects of projects conceived and implemented at ward level; financing of prioritized projects; meetings conducted at sub-ward, ward and council levels and peoples’ awareness on development projects. The least performing cities were Tanga and Zanzibar. While Tanga scored few points in terms of transparency, people’s awareness, civic engagement and enactment of local by-laws, Zanzibar also scored few points in financing of prioritized projects, skills availability, modernization of services and enactment of by-laws. Other cities and municipalities were performing modestly as indicated in Table 3. However, Zanzibar was doing very well in terms of civic engagement especially in participation in electing political leaders.

The overall picture that emerges from this analysis draws its basis from the transitional phases through which Tanzania has been going through; both the economic transformation from planned economy to market or liberal and the political transformation from single party state to multiparty politics have had far reaching influences on these patterns of urban governance. Therefore these variations are partly attributed to these transformations and how each city strived to remain competitive and tape comparative advantages to the changing circumstances.

In order to address weak performance in some parameters, the government of Tanzania initiated the Local Government Reform Programme as a vehicle for implementing Decentralization by Devolution (D-by-D) (PMO- RALG, 1998) . This programme was conceived as a major strategy to empower Local Government Authorities (LGAs) to effectively perform their functions and responsibilities. The overall objective was to make them accountable, legitimate, transparency and participatory and largely autonomous in managing and discharging their social, cultural, economic and environmental functions.

Some of the key objectives of the LGRP included: facilitate the participation of people in deciding on matters affecting lives, planning and executing their development programmes; cost effective and efficient delivery of services; foster development and accountability to the people; financial decentralization to allow the Local Government Authorities to pass own budgets reflecting their own priorities and expenditure required by legislation and national standards; The Decentralization by Devolution strategy was based on the application of principle of “subsidiarity” (PMO-RALG, 1998) . The achievements in these objectives still remain as a major challenge in

Figure 9. Funds spent for land acquisition and development (TZS Billion).

Table 3. Cross case analysis.

most of the urban centres of Tanzania. One of the limiting factors has been the reluctance by the central government to devolve powers to the primary levels of urban governance.

7. Conclusion and Recommendations

This paper has empirically shown that although Tanzania has made some notable strides towards achieving good urban governance, still there are a number of challenges that ought to be addressed. Some of these challenges include: inadequate fiscal decentralization as revealed by overdependence on central government financing, to the tune of 70 percent, uncoordinated partnerships between Civil Society Organizations and urban authorities, human resources and skills deficits, limited financial capacities to acquire land for investment, rapid increase in financial debts, inadequate transparency and political efficacy, poor correlation between the number of enacted By-laws and actual results on the ground, limited political participation and civic engagement of local communities in development projects. This state of governance has been to the large extent attributed to the changing economic and political landscapes through which Tanzania has been passing through. Despite these challenges, there are opportunities that can be tapped for improved urban governance. These include: the local government reforms programme that aims at decentralizing functions to the lower level organs for improved efficiency, increasing trend towards partnership between city councils and CSOs in service provision, high level of bottom-up approaches in planning and project implementation across the cities, increased initiatives towards the use of ICT in municipal operations, satisfactory level of transparency as revealed by adequate number of Sub-ward, ward and council meetings. As a way forward towards addressing these challenges and tapping the observed opportunities, there is an urgent need to re-orient the on-going local government reform programmes to ensure that true decentralised functions, powers and mandates are exercised from below. This should be accompanied with capacity building programmes to ensure effective participation of key stakeholders, accountability of all parties involved and transparency in operations carried out by all development stakeholders.

References

- Banachowicz, B., & Danielewicz, J. (2004). Urban Governance―The New Concept of Urban Management: The case of Lodz, Poland, Paper presented in Conference: “Winds of Societal Change: Remaking Post-Communist Cities”. University of Illinois, 18-19 June 2004, 10-12; In Jusoh, H., & Abdul Rashid, A. (2008). Efficiency in Urban Governance towards Sustainability and Competitiveness of City: A Case Study of Kuala Lumpur. International Journal of Social, Education, Economics and Management Engineering, 2, World Academy of Science, Engineering and Technology.

- Cheema, G. S. (1997). Reconceptualising Governance. Discussion Paper, Management Development and Governance Division, Bureau for Policy and Programme Support, UND, New York.

- Lange, F. E. (2009). Urban Governance: An Essential Determinant of City Development: World Vision Institute for Research and Development Friedrichsdorf. Germany.

- Lupala, J. M. (2014). The Social Dimension of Sustainable Development: Social Inclusion in Tanzania’s Urban Centres. Current Urban Studies, 2, 350-360. http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/cus.2014.24033.

- McCarney, P. L. (1996). The Changing Nature of Local Government in Developing Country. University of Toronto, Toronto Press, 45-47.

- Ngware, S., Kironde, J., Manda, P., & Malya, U. (2003). Local Government in Tanzania; A Country Profile, Association of Local Authorities. Unpublished Report of the Association of Local Authorities of Tanzania, Dar es Salaam.

- Prime Minister’s Office Regional Administration and Local Governments (PMO-RALG) (2009). Local Government Reform Programme II, (Decentralisation by Devolution), Vision, Goals, and Strategy, PMO-RALG, Dodoma.

- Prime Minister’s Office Regional Administration and Local Governments (PMO-RALG) (1998). The Local Government Reform Policy Paper, PMO-RALG, Dodoma, Tanzania.

- South African Cities Network (2006). The State of the Cities Report. SACN, South Africa.

- Taylor, P. (2000). Institutional Profile: UNCHS (Habitat)―The Global Campaign for Good Urban Governance. Environment and Urbanization, 12, 197-202. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/095624780001200114

- UN-Habitat (2010) The State of African Cities 2010. UN-Habitat, Nairobi.

- URT (1996). The National Land Policy, Ministry of Lands, Housing and Human Settlements Development, Dar es Salaam.

- URT (1999). The Land Act Number 4 and 5, Ministry of Lands, Housing and Human Settlements Development, Dar es Salaam.

- URT (2000). The National Human Settlements Development Policy, Ministry of Lands, Housing and Human Settlements Development, Dar es Salaam.

- URT (2007). The Urban Planning Act Number 8, Ministry of Lands, Housing and Human Settlements Development, Dar es Salaam.