Open Journal of Business and Management

Vol.03 No.04(2015), Article ID:60156,14 pages

10.4236/ojbm.2015.34034

Social Responsibility Practices in the Marketing of Loans by Microfinance Companies in Ghana, the Views of the Customer

Yaw Brew1,2, Junwu Chai1, Samuel Addae-Boateng1,2, Solomon Sarpong3,4

1School of Management & Economics, University of Electronic Science & Technology of China, Chengdu, China

2Faculty of Business and Management Studies, Koforidua Polytechnic, Koforidua, Ghana

3School of Computer Science, University of Electronic Science & Technology of China, Chengdu, China

4Department of Statistics, University for Development Studies, Navrongo, Ghana

Email: y.brew@yahoo.com

Copyright © 2015 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 12 August 2015; accepted 5 October 2015; published 8 October 2015

ABSTRACT

Microfinance companies provide loans and other facilities like savings, insurance, and transfer services to poor low-income household and microenterprises. It is expected that by the nature of their customers and services, microfinance companies will be strictly socially responsible in dealing with customers to protect and preserve their rights, but this is not always the case. This research observes the views and concerns of customers about the social responsibility practices of microfinance companies in Ghana, especially, the customer’s right to be informed, to be safe, to choose, and to be heard. The sample is drawn from two major cities, the Accra Metropolis and Kumasi Metropolis of Ghana, and the respondents constitute past and present customers of microfinance companies providing services under the Tier-2 category of microfinance institutions in Ghana. The analysis of the data shows that respondents perceive microfinance companies having transacted with not doing much to ensure that the customer’s rights are protected. Based on the analysis and results of the survey, recommendations are made to managers of microfinance companies and the Ghana Association of Microfinance companies.

Keywords:

Social Responsibility, Microfinance, Loans, Customers’ Rights

1. Introduction

The marketing concept is a philosophy of customer service and mutual gain. Its practices lead the economy by an invisible hand to satisfy many and changing needs of many consumers. When the number of firms in an industry increases, competition also increases, which in most of the time result in aggressive marketing and sales tactics.

The number of microfinance firms in Ghana has been increasing at a faster rate over the last decade with firms springing up in almost every corner in the cities and towns. As at March 2014, the number of microfinance companies operating in the country with the Bank of Ghana’s approval was 394, which represented a little over one hundred percent jump since 2012, [1] . By June 2014, the Bank of Ghana had licenced about 435 microfinance companies and declined 120 applications, with over 200 more pending [2] . As the number of microfinance firms increases, competition also becomes keen and some firms fall into the trap of employing all sorts of unethical practices in getting customers and prospective customers to patronise their services.

Microfinance encompasses the provision of financial services and the management of small amounts of money through a range of products and a system of intermediary functions that are targeted at low income clients. Microfinance refers to the provision of small loans and other facilities like savings, insurance, transfer services to poor low-income household and microenterprises. Microcredit also refers to a small loan to a client made by a bank or other institutions [3] [4] .

It is expected that by the nature of their customers and services, microfinance companies will be strictly socially responsible in dealing with customers and prospective customers to protect and preserve their rights, but this is not always the case.

The main objective of this research was to study the social responsibility practices of the microfinance companies in Ghana, from the perspective of customers. Specifically, the four basic rights of customers:

1. The right to be informed;

2. The right to be safe;

3. The right to choose;

4. The right to be heard.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Nature of Marketing

The marketing concept is a philosophy of customer service and mutual gain. It assumes that the achievement of a company’s goals depends on the determination of a target market needs and wants and delivering of the desired satisfactions more effectively and efficiently than what competitors do. According to Kotler et al. [5] the marketing concept starts with a well-defined market, focuses on customer needs, coordinates all the marketing activities affecting customers and makes profits by creating long-term customer relationships based on customer value and satisfaction. Under the marketing concept, customer focus and value are paths to sales and profits.

Marketing has been defined by different scholars and professional bodies in different ways, in the view of Dibb et al. [6] marketing consists of individual and organizational activities that facilitate and expedite satisfying exchange relationships in a dynamic environment through the creation, distribution, promotion and pricing of goods, services and ideas. To Jobber [7] marketing is the achievement of corporate goals through meeting and exceeding customer needs better than the competition. Kurtz and Boon [8] posits that marketing is the process of planning and executing the conception, pricing, promoting and distribution of ideas, goods, and services, organisation, and events to create and maintain relationships that will satisfy individuals and organisational objectives. Kotler and Armstrong [9] opine that marketing is the process by which companies create value for customers and build strong customer relationships in order to capture value from customers in return. According to the American Marketing Association [10] , marketing is the activity, set of institutions, and processes for creating, communicating, delivering, and exchanging offerings that have value for customers, clients, partners, and society at large. Also, the Chartered Institute of Marketing UK [11] , marketing is the management process responsible for identifying, anticipating and satisfying customer requirements efficiently and profitably. Kotler et al. [5] , state that marketing is a social and managerial process by which individuals and groups obtain what they need and want through creating and exchanging products, and value with others.

From the above definitions the following can be deduced:

Marketing should be embraced by companies who wish to be successful as a management concept and not an activity. If a business is to succeed, then all employees and departments must make the customer their business; in other words, they should place the customer at the centre of all their decisions.

Identifying and anticipating customer needs require organizations to constantly research and develop products and services that best suit customers’ current and future needs. Firms cannot afford to be in tune with the customer today and out of date with the customer tomorrow.

Profitably means organizations should engage in providing products and services that satisfy customers’ needs at a price that customers will appreciate and also be able to make profit. It is of no use to provide goods and services to customers at a price that the firm cannot realize profit neither in the short term or long term.

2.2. Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR)

It is an obvious and undeniable fact from literature that today’s businesses are required to be ethically and morally upright (socially responsible) in managing its affairs with its stakeholders. It is in this vein that Kotler [12] suggested that marketers and management of firms should go beyond the “marketing concept” philosophy and practice what he calls “societal marketing concept”, which takes into consideration the environment and indeed the interests of consumers and the society as a whole in facilitating the flow of goods and services. This is to say that the long term growth and survival of a business does not rest solely on financial gains such as profits but also on prudent management and the satisfaction of the needs of various stakeholders of the business. Thus com- panies or businesses must think and act responsibly.

Despite the growing concern toward the issue of social responsibility, the concept is an ambiguous one with unclear boundaries and debatable legitimacy [13] - [15] and has been defined in various ways. According to The European Commission [16] , most definitions of corporate social responsibility describe it as a concept whereby companies integrate social and environmental concerns in their business operations and in their interaction with their stakeholders on a voluntary basis. Being socially responsible means not only fulfilling legal expectations, but also going beyond compliance and investing “more” into human capital, the environment and the relations with stakeholders.

According to Pirsch et al. [17] , CSR is the company’s “status and activities” regarding its responsiveness to its perceived societal obligations as they apply to all company stakeholders.

CSR is the alignment of business operations with social values. CSR consists of integrating the interests of stakeholders―all those affected by a company’s conduct into the company’s business policies and actions. CSR focuses on the social, environmental, and financial success of a company―the so-called triple bottom line with the goal to positively impact society while achieving business success [18] .

According to Mackenzie [19] , companies see non-compliance with corporate responsibility standards as a significant source of risk to their reputations with customers, employees and other stakeholders. Mackenzie further argues that corporate responsibility is not just perceived to be about avoiding risk. Companies also see strong performance in this area as a source of opportunity to strengthen trust in their brands and to enhance employee motivation. As stated by Singhapakdi [20] , in the long run, ethics and social responsibility should have positive impacts on the success of the organisation, because ethical judgements are likely to influence the consumer acceptance or rejection of a company’s products.

2.3. Ethical CSR

Carroll [21] [22] , suggested four categories of social responsibilities that society expects businesses to assume, which further influenced his definition of CSR. The social responsibility of business encompasses the economic, legal, ethical, and discretionary expectations that society has of organizations at a given point in time. Carroll’s economic responsibilities included being profitable for shareholders, while providing economic benefits to other corporate stakeholders, such as fair-paying jobs for employees and good quality, fairly-priced products for customers. Legal responsibilities involve conducting business legally. Ethical responsibilities go beyond the law by avoiding harm and social injury; respecting people’s moral rights, and doing what is right, just, fair and caring. Lantos [16] stresses that ethical CSR is morally mandatory even if the business might not benefit from it.

Ethical CSR is sometimes framed as a way to respect stakeholders’ rights, [23] . Of special interest to marketers are president John F. Kennedy’s “Consumers’ Bill of Rights”, in 1962, in which he enumerated four basic consumer rights; the right to be safe, to be informed, to choose, and to be heard [5] [23] .

2.3.1. The Right to Be Safe

Businesses should ensure that their products and services are safe to use. This consumer’s right is covered by legislation in many countries.

2.3.2. The Right to Be Informed

Consumers have the right to information necessary for making informed purchasing choices, in addition to the right to protection against intentionally misleading, deceitful or fraudulent products and service information, labelling and marketing.

2.3.3. The Right to Choose

In theory this should encourage competition, but if of course there is competition, marketers will be trying to influence consumer choice. Therefore the right to choose could be seen as less important provided customers are fully informed: however the right to choose might also be interpreted as the right to choose without being unduly pressurized, thus discouraging unsolicited marketing and pressurized selling.

2.3.4. The Right to Be Heard

Consumers have the right to have their concerns heard and considered fully and fairly in accordance with laws governing the providers and development of goods and services. That is the right to make complaints and know that those complaints will be quickly and fairly answered.

2.4. Overview of Microfinance in Ghana

The concept of microfinance is not new in Ghana. Traditionally, people have saved with and taken small loans from individuals and groups within the context of self-help to start businesses or farming ventures. Available evidence also suggests that the first Credit Union in Africa was established in Northern Ghana in 1955 by Canadian Catholic Missionaries. “Susu”, which is one of the current microfinance methodologies, is thought to have originated in Nigeria and spread to Ghana in the early twentieth century [3] [4] .

The term microfinance refers to a development tool that grants or provides financial services and products such as very small loans, savings, micro-leasing, micro-insurance, and money transfer to assist the very or extremely poor in growing or establishing their businesses. It is mostly used in developing economies where small and medium enterprises do not have access to other sources of financial assistance [24] .

Microfinance encompasses the provision of financial services and the management of small amounts of money through a range of products and a system of intermediary functions that are targeted at low income clients. Microfinance refers to provision of small loans and other facilities like savings, insurance, transfer services to poor low-income household and microenterprises. Microcredit also refers to a small loan to a client made by a bank or other institutions [3] [4] .

In Ghana, the term microfinance is understood as a sub-sector of the financial sector, comprising mostly of different financial institutions who use a particular financial method to reach out to the poor and small businesses. Microfinance sector in Ghana comprises various types of institutions and these have been grouped into four (4) categories. These are:

1. Formal suppliers such as savings and loans companies, rural and community banks, as well as some development and commercial banks;

2. Semi-formal suppliers such as credit unions, financial non-governmental organisations (FNGOs), and cooperatives;

3. Informal suppliers such as “Susu” collectors and clubs, rotating and accumulating savings and credit associations (ROSCAs and ASCAs), traders, moneylenders and other individuals;

4. Public sector programmes that have developed financial and nonfinancial services for their clients [3] [4] .

3. Research Problem and Objectives

Research has shown that as the number of competing firms in an industry increase, competition among the firms become keen and aggressive. In such situations firms are expected to benefit from customer loyalty by the continuous provision of services that ensure customer satisfaction. However, it appears that in the face of increasing competition some microfinance firms adopt unethical marketing practices that affect the rights of their customers or clients.

The following questions were asked by the researchers to help give direction and scope to the research as a way of addressing the research problem:

1. Do microfinance firms adequately inform customers and ensure customers understand information about loans and other financial transactions?

2. Do microfinance firms adequately ensure the safety of customers in loans and other financial transactions?

3. Do firms adequately provide the means for the customer to complain and see to it that complaints are resolved?

4. Do microfinance firms provide reasonable variety of services to ensure customers make their choice in loan acquisition and payment?

4. Methodology

This survey was limited to assessing customers’ views on the social responsibility practices of microfinance companies with regards to customers’ right to information, choice, safety and the right to be heard. The research employed the survey method in selecting respondents for the study. The sample was drawn from two major cities, the Accra Metropolis and Kumasi Metropolis of Ghana, which constitute the most populous and commercially centered business areas of the country. Accra doubles as the regional capital of the Greater Accra region and the capital city of Ghana, and Kumasi is the regional capital of the Ashanti region. The Accra metropolis recorded a figure of 1,848,614 and the Kumasi metropolis recorded a figure of 2,035,064 during the 2010 Population and Housing Census [25] . The large population as well as rigorous commercial activities in the two cities have resulted in the establishment of many financial institutions including several microfinance institutions.

The data used were collected from 562 respondents from the Accra and Kumasi metropolis of Ghana, a sub- Saharan economy in Africa. The respondents constitute past and present customers of microfinance companies providing services under the Tier-2 category of microfinance institutions operating in Ghana. Out of this number, 272 representing 48.4% were from the Accra metropolis and 290 (51.6%) were from the Kumasi metropolis.

Convenience and Purposive sampling techniques were used in the administration of questionnaires in these two regional capital cities. Questions were carefully posed in relation to the Ghana Association of Microfinance Companies (GAMC), Members’ Code of Conduct [26] in other to establish whether microfinance companies are being socially responsible. The questionnaire had a total of 35 questions and it was made up of both close-ended and open-ended questions. The questionnaires were personally administered; this offered the researchers the chance to personally seek the consent of the respondents by reading out the consent statement which was boldly written on the questionnaire before the collection of the data, and also, to personally explain some of the questions to respondents who lacked comprehension.

The use of convenience and purposive sampling techniques are consistent with the works of Addae-Boateng et al. [27] - [29] , Brew et al. [30] [31] , Quaye et al. [32] , and suggestions by De Vos [33] and Saunders et al. [34] .

The reliability of the data used for empirical analysis was assessed. The reliability of the data was assured by the use of Cronbach’s alpha (numerical value of 0.5 is considered appropriate to show consistency). For this research data, the alpha value for the customer’s right to be informed is 0.817, the customer’s right to be safe is 0.738, the customer’s right to choose is 0.608, and the customer’s right to be heard is 0.774.

Data collected were sorted, edited, counted and analysed using frequencies, percentages, means and standard deviations. The responses were also subjected to Principal Component Analysis (PCA) using ones as prior communality estimates. The number of components was extracted using the principal axis method. In order to normalise the variation among the variables, Varimax (Orthogonal) Rotation with Kaiser Normalisation was used.

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Demographic Characteristics of Respondents

Table 1 presents the socio-demographic characteristics of the sample used for the research. Among the total number of 562 respondents 61.4% of them were men and 38.6% were women. Almost 30% of the respondents had a bachelor or a Higher National Diploma (HND) qualification, about 26% had Secondary/High school, 24.2% of respondents had Middle school qualification, 10.5% had either technical or vocational qualification while 9.8%

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of respondents.

of respondent had other qualifications. Majority of the respondents (60.5%) were between the ages of 31 - 50 years, 16.5% were between 21 - 30 years, 7.7% were 20 years or less while 15.3% of the respondents were 51 years and above.

5.2. The Customer’s Right to Be Informed

The researchers wanted to know the perceptions of customers about whether microfinance firms adequately provide them with the necessary information concerning loan transactions. As displayed in Table 2, most of the respondents, representing 73.5% agreed with the statement that the loan agreement (contract) was explained to them thoroughly in a medium that they understood before they signed it. More than 19% of the respondents do not agreed with the statement while 7.4% neither disagreed nor agreed with the statement. There were similar responses when respondents were asked whether they were made aware of how they would pay back the loans they took, 67.3% agreed with the statement, but 15.8% disagreed and 16.9% neither agreed nor disagreed.

This suggests that most microfinance firms are behaving well in ensuring that irrespective of the educational level of the customer, the appropriate communication medium is employed so that customers can understand the loan agreement and especially how the loan can be paid back. Also some firms are not using the appropriate media in explaining the loan contract (loan agreement) to the customers, especially how the loans they took would be paid pack.

The respondents’ pre-knowledge of the processing fee and the amount to be paid were also considered; 57.8% respondents agreed that they were made aware that they will pay a processing fee on the loan, 33.4% disagreed with the statement and 8.8% of respondents neither agreed nor disagreed. We wanted to know whether respondents were actually made aware of the amount to be paid as the loan processing fee and the result shows that 58.3% respondents agreed that they were aware of the amount to be paid as the processing fee before the loan was processed, but 33.6% of the respondents disagreed while 8.1% neither disagreed nor agreed.

From the analysis, more than 40% respondents cannot agreed to the fact that they were made aware of a loan processing fee to be paid and the amount to pay. This obviously is not a moral behaviour that a firm should portray. 48.6% of the respondents agreed with the statement that they were made aware of the nature of the interest to be paid for taking the loan, whether flat rate or reducing rate, but 45.4% disagreed with the statement while 6% neither agreed nor disagreed. In responding to the statement as to whether respondents were made aware of the total amount to be paid by the end of the loan period, (that is the principal plus the interest), 49.7% of the respondents agreed with the statement, 37.3% respondents disagreed and 13% respondents neither agreed nor disagreed.

From the analysis, more than 50% respondents are unable to agree with the statement that the microfinance firms they contracted a loan from informed them of the nature of interest on the loan be it a flat rate or a reducing rate and also the total amount to be paid by the end of the loan period.

Table 2. Respondents’ responses to statements about their right to be informed.

The researchers were interested to know if respondents paid any hidden charges in acquiring loans. 40.9% of the respondents agreed that they paid for other charges that they were not aware before signing the loan contract but 42% respondents disagreed that they were made to pay other charges, while 17.1% are not sure whether they paid for other charges or not.

In assessing whether microfinance firms deliver what they promise, 44.6% of the respondents agreed with the statement that microfinance firms deliver on their promises as they portray in their advertisements but 34.6% of the respondents disagreed with the statement, while 20.8% of the respondents neither agreed nor disagreed. Respondents’ views on whether microfinance firms are honest in providing information to customers was evaluated and 53.6% of the respondents agreed with the statement, 25.6% disagreed with the statement that microfinance firms are honest in providing adequate information to customers who wants to take loans from them while 20.8% respondents neither agreed nor disagreed.

Further Analysis

In order to discover or reduce the dimensionality of the data set without sacrificing accuracy or originality; verify new meaningful underlying or hidden patterns within the observed variables in the data, and classify them according to how much of the information stored in the data they account for; we performed exploratory factor analysis. This analysis helped us to identify the number and nature of the latent factors. Using factor loadings of 0.50 and above, the factor scores were selected.

The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure of sampling adequacy value for the factor analysis was 0.83. Also, the Bartlett’s test of sphericity had a chi-square value of 2515.12 with p-value = 0.00.

Using the eigenvalue-greater-than one principle, two factors were retained. These two factors explained about 64% of the variation in the data. The first factor had an eigenvalue of 4.318 explaining about 48% of the variation in the data. Also, the second factor had an eigenvalue of 1.37 and it explained about 16% of the variation in the data.

Much cannot be deduced from the screen plot as it was smooth after component 2, suggesting that only components 1 and 2 account for meaningful variance. This indicates that only these two components should be retained and interpreted.

As displayed in Table 3, from the factor loadings of the rotated component matrix, it was observed that the items; awareness of the interest rate on loan, awareness of the loan processing fee, awareness of the loan processing fee amount, awareness of the loan collection process, thorough explanation of the loan agreement, and awareness of the total loan amount to be paid (Principal Amount and Interest), loaded on factor 1. Hence, factor 1 was called “Loan Transaction Information”. Also, that the statements with regards to: hidden charges, fulfilment of promises portrayed in advertisement, and honesty in providing information, loaded on factor 2. Even though, the item hidden charges, loaded on factor 2, the value was negative. Factor 2 was called General information.

These factors are latent in the sense that they are assumed to actually exist in the responses to the items on the questionnaire, but cannot be measured directly. However, they do exert an influence on the responses to the items that constitute the customer’s right to be informed.

5.3. The Customers’ Right to Be Safe

Customers’ views on whether firms adequately ensure their comfort and safety in loans and other financial tran- sactions were considered. The analysis, as shown in Table 4, indicates that more than 58% of the respondents did not agree with the statement that most of the questions they were asked before the loan was granted were personal and it made them uncomfortable, 23.9% of the respondents agreed that they were asked personal questions which made them uncomfortable and 17.3% of the respondents neither agreed nor disagreed with the statement.

Respondents were asked to respond to a statement whether they felt cheated after contracting a loan. 62% did not agree they felt cheated after taking the loan, 17% agreed they were cheated and 20.4% of the respondents neither agreed nor disagreed with the statement. When respondents were asked if the loan they contracted made them worried because the interest on the loan was too high, 34.2% agreed with the statement but 45.2% disagreed while 20.6% of the respondents neither agreed nor disagreed. This means more that 54% respondents cannot disagree that the interest charged on the loan was too high and that made them worried.

About 52.2% of the respondents disagreed with the statement that the company failed to realize from its assessment that they (the customer) could not repay the loan, 27.9% neither agreed nor disagreed and 19.9% agreed with the statement. Lapses in the loan repayment ability assessment can over burden the customer and deprive him or her, the quality financial advice that they can benefit from credit managers of microfinance com- panies. It is in the interest of these microfinance companies to ensure proper assessment even when loan deductions would be coming from the customers’ source of income (salary).

When respondents were asked whether they have suffered disgrace before as a result of not being able to pay their loan on time, 63.2% of the respondents disagreed that they had been disgraced in any way by the company,

Table 3. Factor loadings of rotated component matrix of responses for customer’s right to be informed.

Table 4. Respondents’ responses to statements about the customer’s right to be safe.

20.6% of the respondents agreed with the statement that they have suffered disgrace from the firm before and 16.2% of the respondents neither agreed nor disagreed with the statement. More than 57% of the respondents disagreed with the statement that the workers of the company talked to them rudely because they were finding it difficult to pay their loan on time, 18.2% agreed with the statement while 24.4% of the respondents neither agreed nor disagreed with the statement. In addition, 29.2% of the respondents agreed that they are now more indebted than before taking the loan but 51.1% of the respondents disagreed with the statement while 19.7% neither agreed nor disagreed.

Further Analysis

The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure of sampling adequacy value for the factor analysis was 0.67. Also, the Bartlett’s test of sphericity had a chi-square value of 1517.23 with p-value = 0.00.

Using the eigenvalue-greater-than-one principle, two factors were retained. These two factors explained about 66% of the variation in the data. The first factor had an eigenvalue of 2.89 explaining about 42% of the variation in the data. Also, the second factor had an eigenvalue of 1.74 and it explained about 24% of the variation in the data.

Much cannot be deduced from the screen plot as it was flat after component 2, suggesting that only components 1 and 2 account for meaningful variance. This indicates that only these two components should be retained and interpreted.

From the factor loadings of the rotated component matrix, as shown in Table 5, it was observed that the items: Failure to detect customers inability to pay back loan, Disgrace for not being able to pay back loan on time, and Worker(s) talked to me rudely for not paying for the loan on time, loaded on factor 1. Hence, factor 1 was named “Payment Inability”. Also, items Personal and uncomfortable questions, I felt cheated after the loan, I was worried because of high interest rate on the loan, and I am more indebted after taking the loan than before loaded on factor 2. Factor 2 was called Dissonance.

These factors are latent in the sense that they are assumed to actually exist in the responses to the items on the questionnaire, but cannot be measured directly. However, they do exert an influence on the responses to the items that constitute the customers’ right to be safe.

5.4. The Customer’s Right to Choose

Respondents’ views on the customer’s right to choose were examined and as shown in Table 6, more than 31%

Table 5. Factor loadings of Rotated Component Matrix of responses for the customers’ right to be safe.

Table 6. Respondents’ responses to statements about the customer’s right to choose.

of the respondents were of the view that the firms do not have different time periods from which one can decide to pay back the loan, but 50.4% of the respondents disagreed with the statement while 18% neither agreed nor disagreed. Also, 52.2% of the respondents were of the opinion that the firm lacks different payment options or modes through which customers can pay back loans, but 25.8% have an opposite view and 22% of the respondents did not agree nor disagree with the opinion.

More than 45% of the respondents agreed with the statement that the penalty charged to surrender a loan is so high that customers have to painfully comply with the agreed payment schedule even if the loan could be paid off, 38.2% disagreed with the statement while 16.4% neither agreed nor disagreed. In addition, 48.5% of the respondents are of the opinion that they were compelled into taking a particular loan package because there were no options available for them, but 35.6% of respondents have an opposite view, while 15.9% neither agreed nor disagreed with the view. In a related score, 28.5% of the respondents later found out that there was a better package but they had already taken the loan, but 53.4% disagreed that they later found out there was a better, and 18.1% neither agreed nor disagreed with the statement.

Further Analysis

The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure of sampling adequacy value for the factor analysis was 0.50. Also, the Bartlett’s test of sphericity had a chi-square value of 262.16 with p-value = 0.00.

Using the eigenvalue-greater-than one principle, two factors were retained. These two factors explained about 56% of the variation in the data. The first factor had an eigenvalue of 1.63 explaining about 33% of the variation in the data. Also, the second factor had an eigenvalue of 1.17 and it explained about 23% of the variation in the data. Much cannot be deduced from the screen plot as it was smooth after component 2, suggesting that only components 1 and 2 account for meaningful variance. This indicates that only these two components should be retained and interpreted.

The factor loadings are presented in Table 7. From the rotated component matrix, it was observed that items: Absence of different loan payback periods, and Unknown loan package loaded on factor 1. Hence, factor 1 was called “Available loan packages”. Also, items, lack of loan payment options, prohibitive loan surrender penalty charge, and I was compelled into taken the loan loaded on factor 2. Factor 2 was called “lack of options”.

These factors are latent in the sense that they are assumed to actually exist in the responses to the items on the questionnaire, but cannot be measured directly. However, they do exert an influence on the responses to the items that constitute customers’ right of choice.

5.5. The Customer’s Right to Be Heard

As shown in Table 8, more than 57% of the respondents agreed with the statement that workers of microfinance companies are always ready to listen to complaints when a customer goes to the office to make a complaint but 26.3% disagreed, while 16% neither agreed nor disagreed with the statement. Likewise, 55% of the respondents agreed with the statement that workers are always ready to listen to a complaint when called on their office phone, 28.1% disagreed with the statement while the remaining 16.9% respondents neither agreed nor disagreed. Similarly, 55.7% agreed it is often very easy to get through to workers on their office line, but 27.5% disagreed with the statement and 16.8% neither agreed nor disagreed.

Table 7. Factor loadings of rotated component matrix of responses for the customer’s right to choose.

Table 8. Responses to the statement the customer’s right to be heard.

When respondents were asked whether workers follow through complaints and resolve problems on time when reported, 55% agreed and 27.9% disagreed with the statement while 17.1% neither agreed nor disagreed. In addition, 60.1% of respondents were of the view that workers are always ready to help solve a complaint, 24% disagreed that workers follow through complaints and resolve problems on time when reported while 15.9% neither agreed nor disagreed.

Further Analysis

The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure of sampling adequacy value for the factor analysis was 0.77. Also, the Bartlett’s test of sphericity had a chi-square value of 1503.06 with p-value = 0.00. Using the eigenvalue-greater-than one principle, two factors were retained. These two factors explained about 68% of the variation in the data. The first factor had an eigenvalue of 3.00 explaining about 49% of the variation in the data. Also, the second factor had an eigenvalue of 1.15 and it explained about 19% of the variation in the data. Much cannot be deduced from the screen plot as it was smooth after component 2, suggesting that only components 1 and 2 account for meaningful variance. This indicates that only these two components should be retained and interpreted.

The factor loadings are presented in Table 9. From the rotated component matrix, it was observed that items: workers are always ready to listen to complaints in their office, workers are always ready to listen to complaints on the telephone, and it is easy to get through the office line, loaded on factor 1. Hence, factor 1 was called “complain making”. Also, items workers readiness to solve problems, and prompt complaint and Problem resolution, loaded on factor 2. Factor 2 was called “complaints resolution”.

These factors are latent in the sense that they are assumed to actually exist in the responses to the items on the questionnaire, but cannot be measured directly. However, they do exert an influence on the responses to the items that constitute the customer’s right to be heard.

5.6. Effect of CSR on Future Loan Transaction Behaviour of Customers

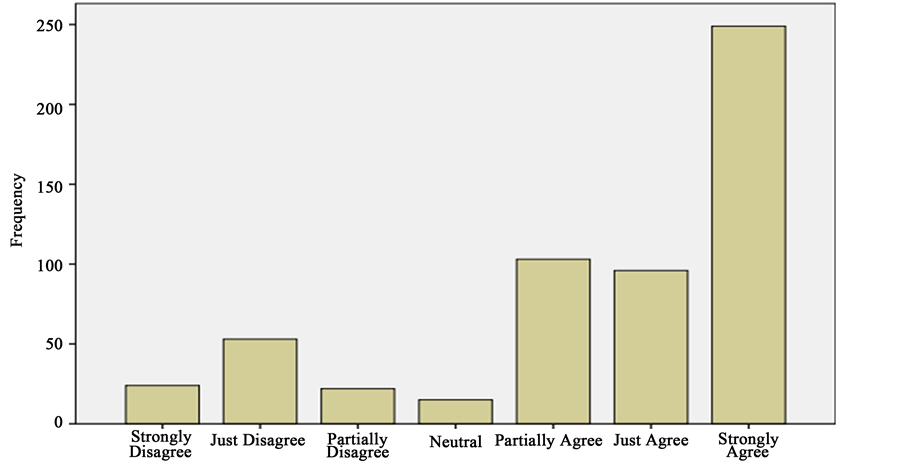

We wanted to know whether respondents would continue to contract loans from microfinance companies whom they know to be socially irresponsible but offer loans with relatively lower interest rates. As shown in Figure 1 and Table 10, more than 79% of the respondents agreed that in the future they will not transact with a firm that is not socially responsible even if their interest rate is relatively low, 17.6% disagreed with the statement and would transact with microfinance companies who are not socially responsible if their interest rate is relatively low while 2.7% neither agreed nor disagreed with the statement.

Table 9. Factor loadings of rotated component matrix of responses for the customer’s right to be heard.

Table 10. Effect of CSR on customers’ future transaction behaviour.

Figure 1. The effect of social responsibility on customers’ future transaction behavior.

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

6.1. The Customer’s Right to Be Informed

Obviously, from the analysis of the data collected, there is a deficiency in the adequacy of information that most microfinance companies provide their customer or client.

Management should ensure that all the important terms and conditions of a loan are clearly stated and the employees are well abreast with these terms and conditions as and when changes are done. Particular attention should be given to the medium, and the information given so as to be well understood by the customer(s). We further recommend that communication of the terms and conditions of a loan must be done face-to-face. Also, a printed copy of the terms and conditions of the loan should be given to the customer(s) to enhance better understanding and as a reference.

6.2. The Customer’s Right to Be Safe

The customer service employees must be trained regularly to facilitate their ability to handle customers in a more humane manner. The responses from the respondents show that they are not happy with the attitude of the service providers. In lieu of this, a structured list of important and appropriate questions should be readily available to help employees do a good assessment of customers. This, to a large extent, will help to offer good financial advice to protect the customer from over indebtedness which may lead to bad debts for the company. Management should take steps to charge a reasonable interest on loans so as not to create the impression that the company is extorting the poor customer.

6.3. The Customer’s Right to Choose

It is the right of the customer to decide and choose. This right should not be undermined by any company. From the responses, most of the respondents are of the view that the microfinance companies they have transacted did not do much to ensure the customer’s right of choice. Most respondents see the companies as not having different loan payment options and different time periods for paying back loans. Others also have the view that the penalty charged to surrender a loan is very high. Customers also complain that they feel compelled into taking a particular package because there is no other options. Also, some customers later realize that there are better loan packages that suit their situation.

In order to maintain customers and still be viable, management should introduce different options that customers can choose from to pay back loans that they have taken. Management should ensure that prohibitive loan surrender charges are avoided. Furthermore, all available loan options should be made known to customers and should not be assumed the customer knows.

6.4. The Customer’s Right to Be Heard

From the analysis, it can be observed that, some of the respondents do not agree that microfinance companies take adequate measures to ensure that the customer’s right to be heard is respected, hence this aspect of customer service delivery should be given the needed attention.

We also recommend that management put in place innovative measures to encourage customer feedback. This will enable management to know and understand their customers well, hence facilitating better service.

Certainly, the importance of the customer’s right to be informed, to be safe, to chose, and to be heard cannot be overemphasized, especially when the social responsibility practices of a company are to be assessed from the point of view of the customer. Management of microfinance companies must have a policy in place to ensure the continuous training of employees in areas, such as product or service knowledge, customer assessment, customer service, and handling of challenging customers. Senior management support and involvement in ensuring ethical and moral behaviour in the running of the company are recommended. In this age of competition, any unethical behaviour from management or employees may result in the company losing the customer(s).

The Ghana Association of Microfinance Companies (GAMC) should continuously and vigorously sensitize and educate the public on the need for customers to do business with their member companies. The association should help brand their member companies well by ensuring compliance to ethical standards and continuous education. The association must vigorously continue in building a reputable and enviable image in the industry so as to attract non-member companies.

7. Limitations and Further Research

This study is limited to the views and concerns of customers of Tier-2 microfinance companies in Ghana. Results are not generalizable to the entire microfinance sector. Further research could include other categories of microfinance companies.

Cite this paper

YawBrew,JunwuChai,SamuelAddae-Boateng,SolomonSarpong,11, (2015) Social Responsibility Practices in the Marketing of Loans by Microfinance Companies in Ghana, the Views of the Customer. Open Journal of Business and Management,03,349-363. doi: 10.4236/ojbm.2015.34034

References

- 1. (2014) Number of Licensed Microfinace Companies Hit Almost 400.

http://www.myjoyonline.com/business/2014/march-7th/number-of-licensed-microfinance-companies - 2. (2014) BoG Backs Down on Microfinance Freeze.

http://business.peacefmonline.com/pages/finance/201406/203917.php - 3. Asiama, J. and Osei, V. (2007) Working Paper. A Note on Microfinance in Ghana. Bank of Ghana.

http://www.bog.gov.gh/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=382:a-note-on-microfinance-in-ghana&catid=125:sector-study-reports&Itemid=249 - 4. Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning—Ghana (MoFEP—Ghana) General Background on Global Microfinance Trends.

http://www.mofep.gov.gh/sites/default/files/pages/microfinance_0.pdf - 5. Kotler, P., Armstrong, G., Sauders, J. and Wong, V. (2002) Principles of Marketing. 3rd Edition, Pearson Education, Essex, England.

- 6. Dibb, S., Simkin, L., Pride, M.W. and Ferrell, O. (2001) Marketing: Concepts and Strategies. 4th Edition, Houghton Mifflin, Boston.

- 7. Jobber, D. (2004) Principles and Practice of Marketing. 4th Edition, McGraw-Hill International, London.

- 8. Kurtz, D. and Boone, E. (2006) Priciples of Marketing. 12th Edition, Thomson Higher Education, Ohio, USA.

- 9. Kotler, P. and Armstrong, G. (2012) Principles of Marketing. 14th Edition, Pearson Education Limited, Essex, England.

- 10. American Marketing Association (2013) Definition of Marketing.

http://www.ama.org/AboutAMA/Pages/Definition-of-Marketing.aspx - 11. The Chartered Institute Of Marketing (2009) Marketing and the 7Ps.

http://www.cim.co.uk/marketingresources - 12. Kotler, P. (1997) Marketing Management: Analysis, Planning, Implementation, and Control. 9th Edition, Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River.

- 13. Pirsch, J., Gupta, S. and Grau, S.L. (2007) A Framework for Understanding Corporate Social Responsibility Programs as a Continuum: An Exploratory Study. Journal of Business Ethics, 70, 125-140.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10551-006-9100-y - 14. Ralston, E.S. (2010) Deviance or Norm? Exploring Corporate Social Responsibility, European Business Law Review, 22, 397-410.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/09555341011056177 - 15. Galbreath, J. (2009) Building Corporate Social Responsibility into Strategy. European Business Law Review, 21, 109-127.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/09555340910940123 - 16. Lantos, G.P. (2001) The Boundaries of Strategic Corporate Social Responsibility. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 18, 595-632.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/07363760110410281 - 17. Carroll, A.B. (1999) Corporate Social Responsibility: Evolution of a Definitional Construct. Business Socity, 38, 268-295.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/000765039903800303 - 18. European Commission (2001) Promoting a European Framework for Corporate Social Responsibilities. COM, Brussels, 366.

- 19. Mackenzie, C. (2007) Boards, Incentives and Corporate Social Responsibility: The Case for a Change of Emphasis. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 15, 935-943.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8683.2007.00623.x - 20. Singhapakdi, A. (1999) Perceived Importance of Ethics and Ethical Decisions in Marketing. Journal of Business Research, 45, 89-99.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0148-2963(98)00069-1 - 21. Carroll, A.B. (1979) A Three-Dimensional Conceptual Model of Corporate Performance. The Academy of Management Review, 4, 497-505.

- 22. Carroll, A.B. (1991) The Pyramid of Corporate Social Responsibility: Toward the Moral Management of Organizational Stakeholders. Business Horizons, 34, 39-48.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0007-6813(91)90005-G - 23. Lantos, G.P. (200) The Ethicality of Altruistic Corporate Social Responsibility. List of Journal Abbreviations, 19, 205-232.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/07363760210426049 - 24. Kimenyi, M.S., Wieland, R.C. and Von Pischke, J.D. (1998) Strategic Issues in Microfinance. Ashgate Publishing, Aldershot.

- 25. Ghana Statistical Service (2012) 2010 Population and Housing Census Final Results Ghana Statistical Service.

http://www.statsghana.gov.gh/docfiles/2010phc/2010_POPULATION_AND_HOUSING_CENSUS_FINAL_ RESULTS.pdf - 26. Ghana Association of Microfinance Companies (GAMC) (2011) Members Code of Conduct. Members Code of Conduct. www.gamcapex.og

- 27. Addae-Boateng, S., Xiao, W. and Brew, Y. (2014) Governance Issues in Family Businesses. International Journal of Economics, Commerce and Management, II, 1-28.

- 28. Addae-Boateng, S., Wen, X. and Brew, Y. (2015) Contractual Governance, Relational Governance, and Firm Performance?: The Case of Chinese and Ghanaian and Family Firms. American Journal of Industrial and Business Management, 5, 288-310.

http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ajibm.2015.55031� - 29. Addae-Boateng, S., Ayittah, S.K. and Brew, Y. (2013) Problems and Prospects of Selling in Reseller Markets in the Fast Moving-Consumer-Goods (FMCG) Industry Using the Sales Force; the Case of Y&K Investments Limited, Koforidua, Ghana. Journal of Business Management, 5, 124-139.

- 30. Brew, Y., Junwu, C. and Addae-Boateng, S. (2015) Corporate Social Responsibility Activities of Mining Companies: The Views of the Local Communities in Ghana. American Journal of Industrial and Business Management, 5, 457-465.

http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ajibm.2015.56045 - 31. Brew, Y., Junwu, C. and Addae-Boateng, S. (2015) Mining Communities’ Perceptions of Corporate Social Responsibility in Ghana. International Journal of Economics, Commerce and Management, III, 514-528.

- 32. Quaye, I., Abrokwah, E., Sarbah, A. and Osei, J.Y. (2014) Bridging the SME Financing Gap in Ghana: The Role of Microfinance Institutions. Open Journal of Business and Management, 2, 339-353.

http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ojbm.2014.24040 - 33. De Vos, A.S. (1998) Research at Grass Roots: A Primer for the Caring Professions. 1st Edition, Van Schaik Publishers, Pretoria.

- 34. Saunders, M.N.K., Lewis, P. and Thomhill, A. (2012) Research Methods for Business Students. 6th Edition, Financial Times/Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River.