Journal of Water Resource and Protection

Vol.08 No.08(2016), Article ID:67736,10 pages

10.4236/jwarp.2016.88062

An Analysis of the Value of Additional Information Provided by Water Quality Measurement Network

François Destandau, Amadou Pascal Diop

GESTE, UMR MA 8101 Engees-Irstea, Strasbourg, France

Copyright © 2016 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 26 January 2016; accepted 25 June 2016; published 28 June 2016

ABSTRACT

European Community policy concerning water is placing increasing demands on the acquisition of information about the quality of aquatic environments. The cost of this information has led to a reflection on the rationalization of monitoring networks and, therefore, on the economic value of information produced by these networks. The aim of this article is to contribute to this reflection. To do so, we used the Bayesian framework to define the value of additional information in relation to the following three parameters: initial assumptions (prior probabilities) on the states of nature, costs linked to a poor decision (error costs) and accuracy of additional information. We then analyzed the impact of these parameters on this value, particularly the combined role of prior probabilities and error costs that increased or decreased the value of information depending on the initial uncertainty level. We then illustrated the results using a case study of a stream in the Bas-Rhin department in France.

Keywords:

Bayesian Decision Theory, Eutrophication, Value of Information, Water Quality Monitoring Network, Water Resource Management

1. Introduction

Water quality monitoring can be defined as the acquisition of quantitative and representative information about the physical, chemical and biological characteristics of a water body over time and space [1] . Water quality monitoring networks appeared in the 1960s and 70s to assess the overall state of resources. For many years, the number, location and frequency of monitoring were the results of practical and subjective considerations, without any ex-post evaluation of the soundness of the initial choice [2] , leading to the production of data that provided little information [3] . It has only been in recent decades that a reflection on the design of monitoring networks has emerged in order to better reflect specific problems such as eutrophication, salinization, acidification and microbial or heavy metal contamination [2] . This has led to studies that deal, for example, with the optimal location of sampling points [4] - [8] .

Other studies have focused on the quantity of information provided by these networks, where information is defined as a reduction of the uncertainty concerning the intensity and transfer of pollutants. Harmanciogluand Apaslan [9] , for a surface water network, and Mogheirand Singh [10] , for a groundwater network, maximized the quantity of information measured by Shannon’s entropy [11] , under cost constraint. Even though it has been accepted that information has a value since the 1950s, the interest in the economic value of this information is much more recent [12] .

Yokota and Thomson [13] describe the analysis of the value of information as the assessment of the benefit of collecting additional information to reduce or eliminate uncertainty in a specific decision-making context. The analyst must therefore identify the set of possible actions and their consequences according to all of the possible states of nature and assess them on the basis of a common measurement. Moreover, he must characterize uncertainties about the states of nature using probability distributions, as well as information-gathering strategies, their precision and their impact on uncertainties. The Bayesian approach makes it possible to calculate the modification of a probability distribution in view of additional information.

This method has been used for different types of additional information and different objectives: information providing the location of a school of fish or the best model to assess their population dynamics [14] , information limiting the uncertainty of depollution costs and the impact of non-point sources on eutrophication in China [15] and, more explicitly, the value of information provided by satellite-based observation systems to combat eutrophication in the North Sea [16] or the destruction of the Great Barrier Reef [17] .

Concerning the value of information generated by water quality monitoring networks, Bouzit, Graveline and Maton [18] present three case studies to assess the value of new pollution measurement techniques, the first aimed at identifying the origin of the pollution through nitrates in groundwater, the second by defining the contribution of two sources to the presence of pesticides in a water table, and the third by detecting accidental toxic pollution in the Rhine. As for Khader, Rosenberg and McKee [19] , they study the value of a monitoring network that makes it possible to assess the risk of contamination due to an excess of nitrates in water.

In this article, we also address the Bayesian method to assess the economic value of additional information, as presented by Yokota and Thomson [13] . The major contribution of this work is the theoretical modeling of the problem, enabling us to better understand the role of each parameter on the value of information, namely: initial assumptions (prior probabilities) on the states of nature, costs linked to a poor decision (error costs) and accuracy of additional information. This study was in fact only partially based on prior work that mainly emphasized empirical applications. In our article, we first define the value of additional information in relation to the parameters mentioned above in order to deduce their impact on this value. We then illustrate our results using an empirical application aimed at assessing the value of additional information generated by a monitoring station. The primary aim of this monitoring station is to assess the eutrophication risk. This enhanced information will therefore make it possible to choose the best technique for an upstream community wastewater treatment plant. The theoretical model is presented in Section 2, and Section 3 is devoted to the empirical illustration of the results. Section 4 concludes.

2. Theoretical Model

2.1. Additional Information as a Decision-Making Tool

Let us assume an additional piece of information about the water quality provided by a monitoring network. This information can be obtained by adding measurement stations, by positioning them more carefully, by increasing the frequency of these measurements and the number of parameters observed, etc. The objective is to define the economic value of this additional information.

The aim of improving our knowledge about water quality is to be able to act more effectively upon it.

We can imagine two states of nature, one more unfavorable for the environment,  , and one more favorable,

, and one more favorable, .

.

Two actions are possible for the decision maker:  and

and , each one corresponding to one of the states of nature, respectively. Given

, each one corresponding to one of the states of nature, respectively. Given , where x is the cost of action in the state of nature s, we have the following equation:

, where x is the cost of action in the state of nature s, we have the following equation:

(1)

(1)

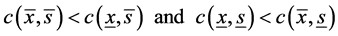

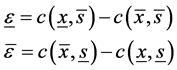

We designate  and

and  as the costs linked to a poor decision (or error costs) by wrongly choosing

as the costs linked to a poor decision (or error costs) by wrongly choosing  and

and , respectively. This is expressed as:

, respectively. This is expressed as:

(2)

(2)

The two error costs are positive. Therefore, neither of the two actions is preferable, regardless of the state of nature. This justifies our search for additional information about the states of nature to reduce the risk of error. The additional information can provide two types of messages,  or

or , indicating that the state of nature “appears” to be

, indicating that the state of nature “appears” to be  or

or .

.

The decision maker will rely on this information to implement his action:

We designate

The probability that this additional information will result in a wrong message is the likelihood function in Bayesian statistics.

2.2. Decision Rule without Additional Information

Additional information only has a value if it allows us to modify the a priori decision (the decision made without additional information). This decision was based on prior probabilities on the states of nature, where p is the prior probability that the state of nature is the most unfavorable:

More precisely, without additional information, a risk-neutral decision maker chooses the action that minimizes the cost expectancy. Therefore,

In the case where

higher error cost due to the choice of

Some authors have attempted to estimate the prior probabilities in a subjective way [18] by questioning the decision makers [16] [17] or by using Monte Carlo simulations [19] . As for us, we question the value of information for all possible prior values.

2.3. Calculation of the Economic Value of Additional Information

The value of information will depend on the economic utility of modifying the decision in view of additional information. By designating

The value of information is written as the sum of utility expectations weighted by the occurrence probability of potential messages that can provide additional information.

According to Bayes’ theorem and our notations (Equation (3) and Equation (4)), we have:

The values of

* 1) For

maker modifies his action a posteriori, i.e., if it conveys the message,

The first two utilities,

* 2) For

maker modifies his action a posteriori, i.e., if it conveys the message,

In this scenario, and for the same reasons as those given in scenario (i), the first utility

2.4. Analysis of the Value of Additional Information

2.4.1. The Value of Additional Information

In Section 2.3 above, we defined the value of information as follows:

If

2.4.2. Impact of the Inaccuracy on the Value of Additional Information

Not surprisingly, we find that information has a higher value when it is more precise.

2.4.3. Impact of Initial Assumptions on the Value of Additional Information

Initial assumptions or a priori probabilities can have a positive or negative influence on the value of information.

If the initial choice is action

In contrast, if the initial choice is

The derivative of

2.4.4. Impact of the Costs of a Poor Decision on the Value of Additional Information

The costs linked to a poor decision or error cost can have a positive or negative influence on the value of information.

If the initial choice is the action

The same reasoning justifies the derivatives of

The derivatives of

maximal value of information (for

The contextualization of the preceding theoretical model will make it possible to illustrate the above results.

3. Empirical Application

3.1. Monitoring Networks in France and in the Bas-Rhin Department

Water quality monitoring networks appeared in France in 1971. Many networks were created over time with different objectives. Some were created before the implementation of the European Water Framework Directive (WFD) in 2007: the National Pollution Survey (Inventaire National du degré de Pollution, INP), the National Basin Network (Réseau National de Bassin, RNB) and the National Complementary Basin Network (RéseauComplémentaire de Bassin, RCB). Others were created afterwards: the Control and Monitoring Network (Réseau de Contrôleet de Surveillance, RCS), the Operational Control Network (Réseau de Contrôle Opérationnel, RCO), the Reference Control Network (Réseau de Contrôle de Référence, RCR), the Survey Control Network (Réseau de Contrôled’ Enquête, RCE) and the Additional Control Network (Réseau de Contrôle Additionnel, RCA). Local networks can be added to these, including the Departmental Interest Network (Réseaud’ Intérêt Départemental) in the Bas-Rhin department (RID 67) that supplements the national networks.

The modification of these networks in 2007 when the WFD was implemented corresponded to a change in the way these networks were designed. Until then, they mainly fulfilled a time-oriented objective, i.e., to measure water quality at a regular frequency at a specific number of measurement stations (generally located on rivers over 10 km long) in order to observe water quality. With the WFD, the objective became space-oriented since information about the quality of each specific water body then became a necessity. This finer spatial grid is accompanied by a rationalization of the measurement frequency that is now linked to observed qualitative problems. A water body that has difficulty in achieving good status will be more closely monitored.

3.2. The Steinbach Measurement Station as a Decision-Making Tool

3.2.1. The Context and Its Formalization

The Steinbach is a stream in the Bas-Rhin department of France. It is 8 km long and flows into the Sauer River, passing through the towns of Dambach, Lembach, Niedersteinbach and Obersteinbach. It is considered to be a water body according to the definition of the European Water Framework Directive and, as a result, has a water quality measurement station that is part of the RID 67, station n˚02045160, located within the city limits of Lembach.

In 2013, a wastewater treatment plant with a population equivalent (PE) of 740 was built in Niedersteinbach in order to collect and treat the effluents of the neighboring communities before discharging them into the Steinbach. Two purification techniques were studied for this treatment plant: activated sludge, which is a biological treatment technique that uses wastewater treatment microorganisms, and a natural lagoon-based wastewater treatment system that uses a bacterial culture to break down organic matter. The activated sludge technique is more costly but more effectively treats the nutrients that can lead to eutrophication when they are discharged into the stream. Eutrophication, which is produced by the proliferation of plants, can have an impact on the fauna and flora by depriving them of oxygen, and generates additional costs to produce drinking water.

When choosing a treatment technique, it is therefore important to know if the environment is sensitive to nutrients and, consequently, if the risk of eutrophication is real. Is it better to use the more costly activated sludge technique to avoid all risks of eutrophication, or the natural lagoon-based system at the risk of having to assume the ecological damage linked to the eutrophication of the water body?

The Steinbach measurement station made it possible to provide information about the sensitivity of the environment so that a well-informed decision could be made.

To calculate the value of this information, we identify:

-two states of nature:

-and two possible actions concerning the choice of the technique to be used at the wastewater plant:

The use of activated sludge will eliminate the risk of eutrophication, regardless of the state of nature:

The use of a natural lagoon-based system will lead to damage linked to eutrophication E of the stream if the environment is sensitive to nutrients:

The costs of a poor decision (Equation (2)) can be expressed as follows:

3.2.2. Value of the Parameters

The Rhin-Meuse Water Agency produces technical datasheets [20] that make it possible to estimate the operating and investment costs for the different treatment techniques according to the population equivalent (PE). For a PE of 740, we have:

Investment cost for lagoon-based system = 676.3 × (740) − 93,858 = ?06,604

Operating cost for lagoon-based system = 3.6501 × (740) + 1117.3 = ?,818/year

Investment cost for activated sludge = 11,023 × (740)0.6159 = ?44,851

Operating cost for activated sludge = 14.454 × (740) + 6433.8 = ?7,130/year

By calculating the constant annuity with a discount rate of 4% and a lifespan of 25 years, we have:

Estimating the damage linked to eutrophication is complicated because it is closely linked to the local context. The water from the Steinbach is not used to produce drinking water, whereas fish farming and recreational fishing could be affected, and the fauna and flora could be subjected to environmental damage. Sutton et al. [21] mention different studies that attempted to estimate this damage. Söderqvist and Hasselström [22] found, for eutrophication in the Baltic Sea, damage of 70 to 800 euros per year and per household. The Aqua Money policy brief [23] for the European Water Framework Directive estimates this damage at between 20 and 200 euros per year and per household for 11 watersheds.

The Steinbach goes through four villages: Dambach (809 inhabitants), Obersteinbach (241 inhabitants), Niedersteinbach (155 inhabitants) and Lembach (1730 inhabitants), with 6%, 77%, 76% and 14% of the municipalities, respectively, located on the water body. We can therefore estimate the number of inhabitants affected by the quality of the water body at 594. With an average household size of 2.3 in France, this means that 258 households are affected, resulting in damage costs of ?8,082 to ?06,647/year basing ourselves on the figures of Söderqvist and Hasselström [22] , and of ?166 to ?1,662/year with Aqua Money [23] .

In order for the information provided by the monitoring station to have value, the damage must be greater than

The aim of this article is not to precisely estimate the damage and, consequently, the value of information, but to instead understand how the parameters influence this value. We illustrate our model with the two upper bounds of the estimates found in the literature, ?1,662 and ?06,647/year.

The error costs (Equation (8)) then become:

3.3. The Value of Information Concerning the Risk of Eutrophication on the Steinbach

Taking the equations used to express the value of additional information described in Equation (6), the error costs given in Equation (9), and the inaccuracy, Equation (3), of 1%, 5% and 10%, Figure 1 shows the evolution of the value of information according to the priori probability that the environment is sensitive to nutrients.

We can see in Figure 1 that when p, the a priori occurrence of eutrophication, is low, the value of information is higher when the damage is greater. In contrast, when p is high, the value of information is higher when the damage is lower.

In fact, if the damage is high (low) and its probability of occurrence is also high (also low), the value of information is low because the choice of opting a priori for activated sludge (natural lagoon-based system) appears to be more appropriate. Additional information in this case therefore provides little information.

In this example, the use of additional information can even lead to a negative value when the additional information is not accurate. In fact, there is a non-null probability that additional information may lead to the modification of a decision that was appropriate a priori.

The greatest a priori uncertainty and, therefore, the greatest value of information is obtained when the damage is high and its probability of occurrence is low, or inversely. The peaks of the graphs in Figure 1 indicate the probability for which uncertainty is a priori maximal for each value of the damage and of the uncertainty of the additional information.

In Figure 2, we can observe the evolution of these “peaks” that express the maximal value of information for different values of the damage.

The limits of these maximal information values for damage that tend towards infinity are, taking Equation (7): ?7,991/year, ?5,706/year and ?2,850/year, respectively, for uncertainties of 1%, 5% and 10%.

4. Conclusions

The European Water Framework Directive is placing increasing demands on the acquisition of information

Figure 1. Value of information according to the ecological damage, the accuracy of additional information and the a priori probabilities on the state of nature.

Figure 2. Maximal value of information according to ecological damage.

about the quality of aquatic environments. In France, the cost of water quality monitoring is estimated at 30 million euros per year. Consequently, a reflection on the rationalization of monitoring networks is necessary. To do this, it is important to estimate the economic value of information produced by a network.

The aim of this article is to contribute to this reflection. To do so, we used the Bayesian framework to define the value of additional information in relation to the following parameters: prior probabilities on the states of nature, costs linked to a poor decision (error costs) and accuracy of additional information. We then analyzed the impact of these parameters on this value, particularly the combined role of prior probabilities and error costs that increased or decreased the value of information depending on the initial uncertainty level. We then illustrated the results using a case study of a stream in the Bas-Rhin department in France.

In the Bayesian framework, the value of information is based on the direct use of this information to influence a decision. The limit of this method is that it does not calculate a value prior to the decision and ignores the future potential uses of the information. In our illustration, this would mean that the Steinbach measurement station would not have any more value once the wastewater station is operational. Nevertheless, even if the Bayesian framework only provides a partial estimation of the value of information, it in no way detracts from its explanatory power.

Knowing the economic value of the information produced by water quality monitoring networks can lead to a cost-benefit analysis to rationalize the design of these networks. To do this, it is also necessary to study the costs of monitoring stations whose calculation is not necessarily direct when certain costs are shared and the frequencies and types of measurements are irregular. However, this is not within the scope of this article.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our deep gratitude to Alain Kieber, head of the Réseaud’ Intérêt Départemental (RID 67) of the Conseil Départemental du Bas-Rhin, for providing us with all of the information necessary to build our case study.

Cite this paper

François Destandau,Amadou Pascal Diop, (2016) An Analysis of the Value of Additional Information Provided by Water Quality Measurement Network. Journal of Water Resource and Protection,08,767-776. doi: 10.4236/jwarp.2016.88062

References

- 1. Sanders, T.G., Ward, R.C., Loftis, J.C., Steele, T.D., Adrian, D.D. and Yevjevich, V. (1983) Design of Networks for Monitoring Water Quality. Water Resources Publication LLC, Highlands Ranch, CO.

- 2. Strobl, R.O. and Robillard, P.D. (2008) Network Design for Water Quality Monitoring of Surface Freshwater: A Review. Journal of Environmental Management, 90, 639-648.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2007.03.001 - 3. Ward, R.C., Loftis, J.C. and McBride, G.B. (1986) The “Data-Rich and Information-Poor Syndrome” in Water Quality Monitoring. Environmental Management, 10, 291-297.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF01867251 - 4. Alvarez-Vazquez, L.J., Martinez, A., Vazquez-Mendez, M.E. and Vilar, M.A. (2006) Optimal Location of Sampling Points for River Pollution Control. Mathematics and Computers in Simulation, 71, 149-160.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.matcom.2006.01.005 - 5. Destandau, F. and Point, P. (2003) Analysecoutefficacitéet discrimination partielle de la redevance. In: Ferrari, S. and Point, P., Eds., Eau et Littoral: Préservation et Valorisation de l’eaudans les Espacesinsulaires, Les Editions Kartala, Paris, 301-330.

- 6. Do, H.T., Lo, S.L., Chiueh, P.T. and Thi, L.A.P. (2012) Design of Sampling Locations for Mountainous River Monitoring. Environmental Modelling & Software, 27, 62-70.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.envsoft.2011.09.007 - 7. Park, S.Y., Choi, J.H., Wang, S. and Park, S.S. (2006) Design of a Water Quality Monitoring Network in a Large River System Using the Genetic Algorithm. Ecological Modelling, 199, 289-297.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2006.06.002 - 8. Telci, I.T., Nam, K., Guan, J. and Aral, M.M. (2009) Optimal Water Quality Monitoring Network Design for River Systems. Journal of Environmental Management, 90, 2987-2998.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2009.04.011 - 9. Harmancioglu, N.B. and Alpaslan, N. (1992) Water Quality Monitoring Network Design: A Problem of Multi-Objective Decision Making. Journal of the American Water Resources Association, 28, 179-192.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-1688.1992.tb03163.x - 10. Mogheir, Y. and Singh, V.P. (2002) Application of Information Theory to Groundwater Quality Monitoring Networks. Water Resources Management, 16, 37-49.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1015511811686 - 11. Shannon C.E. (1948) A Mathematical Theory of Communication. Bell System Technical Journal, 27, 379-423, 623-656.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/j.1538-7305.1948.tb00917.x - 12. Macauley, M. and Laxminarayan, R. (2010) Valuing Information: Methodological Frontiers and New Applications for Realizing Social Benefits. Space Policy, 26, 549-551.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.spacepol.2010.08.007 - 13. Yokota, F. and Thompson, K.M. (2004) Value of Information Analysis in Environmental Health Risk Management Decisions: Past, Present and Future. Risk Analysis, 24, 635-650.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.0272-4332.2004.00464.x - 14. Mantyniemi, S., Kuikka, S., Rahikainen, M., Kell, L.T. and Kaitala, V. (2009) The Value of Information in Fisheries Management: North Sea Herring as an Example. Ices Journal of Marine Science, 66, 2278-2283.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/icesjms/fsp206 - 15. Wu, B. and Zheng, Y. (2013) Assessing the Value of Information for Water Quality Management: A Watershed Perspective from China. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment, 185, 3023-3035.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10661-012-2769-8 - 16. Bouma, J.A., Van der Woerd, H. and Kuik, O. (2009) Assessing the Value of Information for Water Quality Management in the North-Sea. Journal of Environmental Management, 90, 1280-1288.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2008.07.016 - 17. Bouma, J.A., Kuik, O. and Dekker, A.G. (2011) Assessing the Value of Earth Observation for Managing the Coral Reefs: An Example from the Great Barrier Reef. Science of the Total Environment, 409, 4497-4503.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2011.07.023 - 18. Bouzit, M., Graveline, N. and Maton, L. (2013) Assessing the Value of Information of Emerging Water Quality Monitoring. Working Paper, BRGM.

- 19. Khader, A.I., Rosenberg, D.E. and McKee, M. (2013) A Decision Tree Model to Estimate the Value of Information Provided by a Groundwater Quality Monitoring Network. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences, 17, 1797-1807.

http://dx.doi.org/10.5194/hess-17-1797-2013 - 20. Agence de l’eauRhin-Meuse (2007) Les procédésd’épuration des petites collectivités du BassinRhin-Meuse: éléments de comparaison techniques et économiques.

http://cdi.eau-rhin-meuse.fr/GEIDEFile/30228_RM.PDFArchive=170782499896&File=30228+RM_PDF - 21. Sutton, M.A.M., Howard, C.M., Willem Erisman, W., Billen, G., Bleeker, A., Grennfelt, P., Van Grinsven, H. and Grizzetti, B. (2011) The European Nitrogen Assessment. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511976988 - 22. Soderqvist, T. and Hasselstrom, L. (2008) The Economic Value of Ecosystem Services Provided by the Baltic Sea and Skagerrak.

http://www.naturvardsverket.se/Documents/publikationer/978–91–620–5874–6.pdf - 23. Aquamoney (2010) http://www.aquamoney.ecologic-events.de/sites/results.html