The Study of the Impact of Microfinance on Small and Medium Scale Enterprises (SMEs) in Sierra Leone: A Case Study of ECOBANK Microfinance Sierra Leone ()

1. Introduction

The revolution, of microfinance, urban and rural, started in Germany some 150 - 200 years ago from small informal beginnings as part of an emerging self-help movement: with the first thrift society established in Hamburg in 1778; the first community bank in 1801; and the first urban and rural cooperative credit associations in 1850 and 1864, respectively (Seibel, 2006) [1] . The provision of legal status, prudential regulation, and, effectively delegated supervision played a crucial role in their further development, starting with the Prussian Savings Banks Decree in 1838 and the Cooperative Act of the German Reich in 1889, the first cooperative law in the world. Their success has been spectacular. With 39,000 branches, these two types of (micro-)finance institutions now comprise 51.5% of all banking assets in Germany (Dec. 1997 data) and seem far healthier than the big national banks. (Seibel, 2006 [1] ; Seibel 2003 [2] )

The story of Germany is preceded by the earlier, but sadder story of the Irish charities or Irish funds, respectively, which emerged in the 1720s in response to a tremendous increase in poverty (Seibel, 2006) [1] . They started with interest-free loans from donated resources. After a century of slow growth, a boom was initiated by a special law in 1823, which turned charities into financial intermediaries by allowing them to collect interest-bearing deposits and charge interest on loans. Around 1840, around 300 funds had emerged as self-reliant and sustainable institutions, with high-interest rates on deposits and loans. They were so successful that they became a threat to the commercial banks, which responded with financial repression: getting the government to put a cap on interest rates in 1843. The Loan Funds lost thus their competitive advantage, which caused their gradual decline until they finally disappeared in the 1950s. (Seibel, 2006 [1] ; Seibel 2003 [2] )

However, the revolutions in rural and microfinance seem to be recurrent events. One such revolution started in the

1970s, when Shaw and McKinnon (1973) [3] at Stanford University propagated, pertaining to financial systems, the crucial importance of Money and Capital in Economic Development; and a group of scholars around Dale Adams (1984) [4] at Ohio State University, pertaining to rural financial systems, exposed the dangers of Undermining Rural Development with Cheap Credit (Seibel, 2006) [1] . Microfinance is thus not a recent development, and it is a temporary solution for poor countries (Seibel, 2006) [1] .

Microcredit is centered on small-loan facilities for poor people while microfinance is a comprehensive approach that embraces a range of financial services for poor people (Mago, 2013 [5] ; Helms 2006 [6] ). It could be argued that among developing or middle-income countries, microfinance takes root as a poverty mitigation tool and is, therefore, more prevalent in poorer countries (Westley, 2005 [7] ; Allaire et al., 2009 [8] ). There is an increased demand for microfinance because of its ability to meet the capital needs of the poor who could not meet the stiff conditions of accessing loans from the banks that required collateral as an “insurance” against the loan given to their customers; operating in the unregulated, informal sector of the economy (Henry et al., 2003 [9] ; Robinson, 2001 [10] ). The difference between the project size and the microcredit size is generally financed through co-financing schemes with traditional banks (Bourlès & Cozarenco, 2018) [11] .

With the help of the World Bank and other donors, microfinance institutions have vigorously spearheaded strategies mainly for ensuring that small enterprises are catered for through financial loans with low-interest rates. In Sierra Leone, small businesses form the backbone of the economy. Microfinance has a pivotal role to play in the growth of small businesses. The MFIs have been of great importance in West African nations, especially for small firms engaged in the retail sector by providing financial services and boosting their earnings, and empowering society.

Finance in West Africa had been quite scarce and the presence of micro-Finance institutions in these nations had filled the void that was left by commercial banks by providing small loans at the lowest interest rate in the 1980s and 90s. In this context, microfinance institutions have emerged as the viable solution to poverty and empowerment by providing credit and savings services to the multitude of smallholder producers and entrepreneurs to make up the agricultural and entrepreneurial sectors in West Africa. The emergence of micro-finance in Sierra Leone has played a great role in the promotion of small businesses by advancing small loans for business investments. In recent times, Government has also been a key player in the provision of micro-credit to SMEs through the Munafa Funds. Young entrepreneurs are also trained in financial management, especially on how to plan well and access micro-credit for their small business investments. Beneficiaries of microfinance in Freetown Municipality are given advice and training from experts who nurture them with the capability to manage and mobilize resources to develop their small-scale businesses over time. Financial services given by micro-finance institutions in Freetown Municipality significantly play an integral role in helping small-scale business owners leverage their initiative, accelerating the process of building incomes, assets, and economic security. Alleges a large number of small loans are needed to serve the poor people in Sierra Leone.

The inflexible requirements of the commercial banks plus the perception that lending money to low-income businesses was a bad risk contributed to the incapacitated state of the small enterprises to remain inept and hampered in their investment. Over the last decade, however, successful experiences in providing finance to small businesses in Sierra Leone by micro-finance institutions & other players in the market have empirically demonstrated that small businesses, when given access to responsive and timely financial services at lower market rates, with proper business investment advice, could use the micro-credit loans given to them to invest in small scale enterprises to increase income and assets, and later repay their loans at lower interest rates.

The majority of businesses, about 60% percent out of the 100 respondents (SMEs) began their operations between the period 2004 and 2007. It goes on to show that a little over 20% of SMEs who have subscribed to the main MFIs under study, sprung up in the early and late 2000s respectively. This study also identifies that all the respondents (SMEs) started their businesses between 2003-2022. This could be sufficient evidence to support the fact that most SMEs began operations just within the same time frame as the inception of many MFIs within Freetown municipality. Owing to this, one can generally allude to the fact that most of the SMEs sampled for the study were established in the 21st century, a somewhat clear indication of the joint relationship between MFIs and SMEs.

The purpose of this research is to determine the impact of Microfinance on the growth of Small and Medium Scale Enterprises in the Western Urban areas in Sierra Leone.

2. Research Methodology

2.1. Problem Statement

Microfinance has an impact on the growth of Small and Medium Scale Enterprises in the Western Urban areas of Sierra Leone.

2.2. Purpose Statement

The purpose of this research is to determine the effect of Microfinance on the growth of Small and Medium Scale Enterprises in the Western Urban areas in Sierra Leone.

Variables: The independent variable for the research is Microfinance. The dependent is the growth of Small and Medium Scale Enterprises.

The unit of analysis: The unit of analysis for this research is the Medium Scale Enterprises in the Western Urban areas in Sierra Leone.

2.3. Research Question

1) Does the MUNAFA fund have an impact on SMEs’ performance?

2) What is the volume of loans granted by MFIs to SMEs?

3) What are the challenges SMEs in assessing Micro-Credit?

4) What is the rate at which SMEs borrow from MFIs as against other sources of capital?

5) How efficient is the MUNAFA Fund in Supporting Small Businesses?

2.4. Research Method

The Mix Method Approach is used for this research. Data analysis was done using the Mixed Method Approach as the data collected was both quantitative and qualitative in nature. The quantitative data analysis was done by using descriptive statistics and the qualitative data analysis was done using the descriptive research method. A sample size of 120 potential respondents was identified using random sampling techniques. However, only 107 respondents consented to take part in the survey which constituted 89.17% of the total respondents.

2.5. Data Collection

Data collected for the study comprised both primary and secondary data. Primary data consists of data gathered from selected SMEs within the scope of the research field. This was done with the use of an interview guide and well-designed questionnaires. Face-to-face interviews characterized the data-gathering sessions on the field with owners of these selected businesses. Additionally, further information gathered from the individual MFIs was added to the set data gathered as primary data. The secondary data was obtained from the financial records of the two microfinance institutions under study and their existing data on granting loans to SMEs. The study was undertaken using the purposive sampling technique, the research covered strictly the two MFIs and their respective clients.

3. Theoretical Review

The development of financial institutions in Africa can be traced back to the 16th Century when the tribe Yoruba in Nigeria formed Esusu which was a Rotating Savings and Credit Association (RoSCA) (Seibel, 2006) [1] Microfinance, on the other hand, developed gradually and gained expansion from the narrow field of microcredit (Mago, 2013 [5] ; Helms, 2006 [6] ; Elahi and Rahman, 2006 [12] ; Henry et al., 2003 [9] ) [13] . Microfinance as a tool of economic development springs from the banks’ lack of interest in low-income customers and experts who were well-informed about the successes of the market-oriented approach to microfinance in the 1980s and the early 1990s were rather skeptical about downscaling projects (Terberger, 2003) [13] . However, the development of microfinance started on a small scale in 2002 in Sierra Leone, with a number of providers using different models and approaches to provide microfinance (Bayan Global 2002). Sierra Leone is said to have a relatively long history of government initiatives to promote and finance, small and medium enterprises (SMEs). The contributions of these SMEs to the economic development and growth of Sierra Leone are substantial, especially in the area of employment.

Microfinance as a tool of economic development springs from the banks’ lack of interest in low-income customers and experts who were well-informed about the successes of the market-oriented approach to microfinance in the 1980s and the early 1990s were rather skeptical about downscaling projects (Terberger, 2003) [13] .

Hulme and Mosely (1996) [14] focused on the results of institution-building in microfinanceand the conclusion of the research was “The most significant observation must be that non-profit institutions (including public sector and non-governmental organizations) appear to have a comparative advantage over for-profit institutions in providing formal financial sector services to poor people” (Hulme & Mosley, 1996) [14] . Previous research reveals that entrepreneurship generates economic growth (Reynolds et al., 2005 [15] ; Audretsch and Thurik 2001 [16] ; Bourlès & Cozarenco, 2018 [11] ).

There are pieces of evidence in the microfinance literature that proffered microfinance as one of the solutions for global poverty alleviation over the past three decades (Widiarto & Emrouznejad, 2014 [17] ; Koveos & Randhawa, 2004 [18] ; Shaw, 2004 [19] ) and this assertion has brought microfinance into the limelight, particularly in achieving the Millennium Development Goals (MDG) of halving global poverty in 2015 (Widiarto & Emrouznejad, 2014) [17] . Microfinance addresses the banking system’s failure in breaking the vicious circle of poverty (Widiarto & Emrouznejad, 2014 [17] ; Chowdhury & Mukhopadhaya, 2012a [20] ; Conning, 1999 [21] ) by financing the poor who could not meet the rigid conditions of banks’ demands for access to financing; this category of poor people who are referred to as “unbankable” are excluded in accessing financing or loans from the banks as they are classified by the formal banking sector as risky to be provided with loan facilities or financing without collaterals (Simanowitz, 2003 [22] ; Widiarto & Emrouznejad, 2014 [17] ; Di Martino & Sarsour, 2012 [23] ; Vanroose & D’Espallier, 2013 [24] ). In addition, the request of the poor for small loans is deemed unprofitable by the banks (Johnston & Morduch, 2008 [25] ; Widiarto & Emrouznejad, 2014 [17] ).

Morduch (1999) [26] observed that in the past decade, microfinance programs have demonstrated that it is possible to lend to low-income households while maintaining high repayment rates―even without requiring collateral. The programs promise a revolution in approaches to alleviating poverty and spreading financial services, and millions of poor households are served globally. A growing body of economic theory demonstrates how new contractual forms offer a key to microfinance success―particularly the use of group-lending contracts with joint liability high repayment rates have not translated into profits, and studies of impacts on poverty yield a mixed picture. On the other hand, Navajas et al. (2000) [27] research stated that MFIs serve households that are either just below the poverty line―“the richest of the poor”―or just above the poverty line―“the poorest of the rich”―in its strive to be profitable.

Schreiner (2002) [28] developed a framework that encompasses both the poverty approach to microfinance and the self-sustainability approach. The poverty approach assumes that great depth of outreach can compensate for narrow breadth, short length, and limited scope. The self-sustainability approach assumes that wide breadth, long length, and ample scope can compensate for shallow depth. The research further stated the depth of outreach and financial sustainability which is like conflicting objectives thus a trade-off exists: outreach is only attained by sacrificing financial sustainability or by relying more on donations or subsidies. He suggested MFIs strive for breadth, scope, and length aspects of outreach instead of depth (Widiarto & Emrouznejad, 2014 [17] ; Hermes and Lensink, 2011 [29] ; von Pischke, 1996 [30] ; Mersland and Strøm, 2008 [31] ; Hermes et al. (2011) [32] ; and others similarly focused on this trade-off.

Microfinance sustainability is of equal importance as MFI is expected to be operational in the long term for it to have a significant impact on the poor (Widiarto & Emrouznejad, 2014) [17] ; and sustainability is defined as the permanence or the MFI’s ability to sustain its microcredit and other operations as a viable financial institution (Cull et al., 2007 [33] ; Navajas et al., 2000 [27] ; Widiarto & Emrouznejad, 2014 [17] ).

Cull et al. (2007) [33] suggested that MFIs can sustain their profitability by not lending to the poorest, given the higher cost per dollar of loan, but to the “less poor” instead as overall welfare will improve. In addition, this study argued along with Ahmed (2002) [34] , that microfinance is actually a response to the failure of trickle-down development policy to alleviate poverty in most developing countries, owing to asymmetric information (Widiarto & Emrouznejad, 2014) [17] . In addition Cull et al. (2007) [33] observed that Microfinance contracts have proven able to secure high rates of loan repayment in the face of limited liability and information asymmetries, but high repayment rates have not translated easily into profits for most micro finance banks. Profitability, though, is at the heart of the promise that microfinance can deliver poverty reduction while not relying on ongoing subsidies (Widiarto & Emrouznejad, 2014) [17] .

Simanowitz (2007) [35] observed the widespread belief that the social and financial objectives of microfinance operate in opposition to each other and questions the assumption that trade-offs between financial performance and social impact are inevitable and fixed, and provide a framework for increasing performance for social objectives in even the yield-orientated microfinance institutions (MFIs); thus MFI can and should manage objectives trade-off. This is in contrast to the earlier “win-win” vision of MFIs which rapidly reach scale and outreach bringing about positive impacts on large numbers of the world’s poor people, whilst at the same time becoming financially self-sufficient and therefore no longer dependent on external funding. Furthermore, Haq et al. (2010) [36] , Fluckiger & Vassiliev (2007) [37] , and Gutiérrez-Nieto et al. (2009) [38] among others, empirically observed that both outreach and financial sustainability can be pursued in best-practice MFIs (Widiarto & Emrouznejad, 2014) [17] .

Diop et al. (2007) [39] , support the view that the impact of subsidies on the efficiency of microfinance institutions (MFIs) is a key question in the field, given the large volume of subsidies received by Microfinance institutions (MFI) has unique characteristics wherein they face double bottom line objectives of outreach to the poor and financial sustainability while Quayes (2012) [40] observed that the primary justification for subsidizing Microfinance Institutions (MFIs) is their enhancement of social welfare by extending credit to the poor households. Therefore, the recent emphasis on their financial self-sufficiency has created concern, that this may adversely affect the mission of social outreach (Widiarto & Emrouznejad, 2014) [17] .

The advocates of microfinance argue that access to finance can help substantially reduce poverty (Dunford, 2006 [41] ; Littlefield, Morduch, & Hashemi, 2003 [42] ). Research shows that women are more reliable and have higher pay-back ratios. Moreover, women use a more substantial part of their income for the health and education of their children (Pitt & Khandker, 1998 [43] ; Hermes & Lensink, 2011 [29] ).

Research evidence on non-randomized microfinance impact evaluation is mixed (Hermes & Lensink, 2011) [29] [50] and the most popular study in this field is by Pitt and Khandker (1998) [43] on the impact of microfinance in Bangladesh, using household survey data for 1991-92; the findings of this study indicate that the access to microfinance by women increases consumption expenditure. Khandker (2005) [44] , further the study by Pitt and Khandker (1998) [43] using the panel data for 1991-92 and 1999 and observed that the extremely poor benefit more from microfinance than the moderately poor. Roodman and Morduch (2009) [45] contested the results of the foregoing studies showing that the instrumentation strategy may have failed and that results may be driven by variables that were omitted and/or reverse causation problems. Chemin (2008) [46] , following the same trend in the Bangladesh surveys, applies the propensity score matching technique and finds that access to microfinance has a positive impact on expenditures, supply of labour, and school enrollment. Copestake, et al. (2005) [47] on the other hand are less optimistic about the impact of microfinance. Based on data from a survey carried out in collaboration with a village banking program, using a mix of evaluation methods (among which are the difference-in-difference approach and qualitative in-depth interviews) find that it is the “better off” poor rather than the core poor who benefit most from access to microfinance (Hermes & Lensink, 2011) [29] .

Hermes & Lensink, (2011) [29] , observed the disagreement about the contribution of microfinance in the literature on the reduction of poverty impact of microfinance that has propelled huge attention to empirical assessments. Hence researchers have endeavoured to address one or more of the three following questions: 1) does microfinance reach the core of the poor or does it predominantly improve the well-being of the better-off poor; 2) which contribution is seen as the most important (improvement of income, accumulation of assets, empowerment of women, etc.); and 3) do the benefits outweigh the costs of microfinance schemes? (Chemin, 2008 [46] ; Dunford, 2006 [41] ). The latter issue deals with the question of to what extent subsidies to microfinance organizations are justified. Most studies aiming at evaluating the impact of microfinance address the first of the above three issues. Even though several assessments of the impact of microfinance on poverty reduction have been made, there is surprisingly little solid empirical evidence on this issue. The major problem with respect to investigating the impact of microfinance is how to measure its contribution to poverty reduction. Several studies measure the impact of microfinance by comparing recipients of microfinance with a control group that has no access to microfinance. In most cases, these studies apply non-randomized approaches. These approaches may be problematic, however. The changes in the social and/or economic situation of the recipients of microfinance may not be the result of microfinance. For instance, it is well-known that relatively rich agents are less risk-averse than relatively poor agents. This may induce rich agents to apply for microfinance whereas poor agents do not apply, that is, there may be a self-selection bias. In this situation, an ex-post comparison of the income of the two groups may lead to the incorrect conclusion that microfinance has stimulated income. In addition, in order to improve the probability of microfinance being successful, MFIs may decide to develop their activities in relatively more wealthy regions (i.e., nonrandom program placement). Obviously, this biases any comparison between recipients of microfinance and the control group (Armendariz de Aghion & Morduch, 2005 [48] ; Karlan, 2001 [49] ).

Hulme (2000) [50] , observed that Impact assessment (IA) studies are of increasing interest to donor agencies. While the goals of IA studies commonly incorporate both “proving” impacts and “improving” interventions, IAs are more likely to prioritize the proving goal than did the evaluations of the 1980s. Explicitly, IAs are promoted by both the sponsors and implementers of programs so that they can learn what is being achieved and improve the effectiveness and efficiency of their activities. Implicitly, IAs are a method by which sponsors seek to get more information about program effectiveness than is available from the routine accountability systems of implementing organizations. IAs are also of significance to aid agencies in terms of meeting the ever-increasing accountability demands of their governments (in this era of “results” and “value for money”) and for contesting the rhetoric of the anti-aid lobby. While recipient agencies benefit from this, they are one stage removed, and many are likely to see donor-initiated IA as an activity that has limited practical relevance for program activities.

Based on the theoretical review of our study it is crystal clear the literature on microfinance is mixed, however, different approaches have been used to arrive at different results, and in some cases, the same approaches were used as an extension of previous studies. Some studies critic the results of other researchers.

The purpose of this research is to determine the impact of Microfinance on the growth of Small and Medium Scale Enterprises in the Western Urban areas in Sierra Leone. As the study on impact has been significantly endorsed in the Microfinance literature hence its study in Sierra Leone is eminent.

4. Small and Medium Scale Enterprises (SMEs) in Sierra Leone

4.1. Concept of SMEs in Sierra Leone

In Sierra Leone, available data from the Registrars’ General Department indicated that 80% of companies registered are micro, small, and medium enterprises. This target group has been identified as the catalyst for the economic growth of the country as they are a major source of income and employment. Data on this group is however not readily available. The Ministry of Trade and Industry estimated that the Sierra Leonean private sector consisted of approximately 16,000 registered limited companies and 22,000 registered partnerships. Generally, this target group in Sierra Leone is defined as:

1) Micro enterprises―they are businesses that employ up to 5 employees with fixed assets (excluding real estate) not exceeding the value of $10,000;

2) Small enterprises―are businesses that employ between 6 and 29 employees with fixed assets of $100,000; and

3) Medium enterprises―they are business entities that employ between 30 and 99 employees with fixed assets of up to $1 million.

The definition of Small and Medium Enterprises Development Agency in Sierra Leone applies both the “fixed asset and a number of employees” criteria; hence, it defines a Small Scale Enterprise as one with not more than 9 workers with ownership of plant and machinery (excluding land, buildings, and vehicles) not exceeding 10 million Leones (an equivalent of USD 600).

4.2. Purposes of Establishing SME

In establishing SMEs, various objectives are taken into consideration before establishment before the SME becomes operational. When respondents were asked about these objectives; varied objectives were given such as summarised below:

・ To generate income to support their family’s well-being.

・ To serve the community.

・ To support the growth of the Sierra Leonean economy.

・ To create employment opportunities for other Sierra Leoneans.

・ To be self-employed.

5. Discussion

The data collected was analyzed to inform our discussions, conclusions, and recommendations to practice and further research. The study had a sample population of 120 potential respondents identified for the questionnaires. However, only 107 respondents consented to take part in the survey. During data entry and cleaning, it was realized that 9 respondents gave contradicting and inconsistent data which led to the study eliminating them from the analysis of the study data. The remaining 98 respondents were considered valid and their responses were analyzed in the study giving a valid response rate of 81.67% was considered sufficient for the analysis. The questionnaires distributed were divided into two categories, one category for SMEs and the other for MFIs. A total of 120 questionnaires were distributed for responses and from the 120 questionnaires given to respondents, 107 were received representing an overall response rate of 89.17%. However, as the result of 9 respondents contradicting and inconsistent data the data analysis was directed at 98 respondents made up of 2 completed questionnaires from MFIs and 96 questionnaires collected from the SMEs. Table 1 indicates the analysis of valid data collected (valid data refers to the 98 respondents after data clean-up).

The analysis of research questions based on evidence drawn from our respondents was done chronologically and understandably Research Question is referred to as R.Q.

R.Q 1: Does the MUNAFA fund have an impact on SMEs performance?

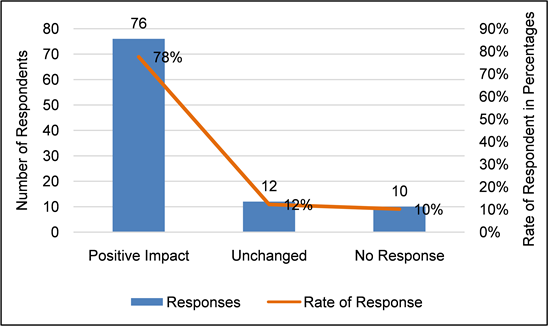

The responses from the respondents show that have a positive impact on the performance of SMEs. When SMEs were asked whether the existence of Munafa Funds has had any impact on their business, it was found that the majority of them, precisely, 78 percent recorded a positive impact as the Munafa Fund assisted the growth of their businesses also lead to the increase in the number of employees, and were able to meet family needs, while 12 percent of businesses remained unchanged but accentuated to stability in their businesses. This analysis is shown in Figure 1. However, none of the respondents indicated a negative effect of the existence of MFIs on their business but all the respondents accentuated stability as a positive indication of MFIs’ impact on SMEs and this helps to reduce the poverty burden. The women respondent within the stability category further explains that with access to the Munafa Fund, they were able to meet the needs of their children in school, provide meals at home, and were able to maintain a stable business. Our findings are consistent with previous research which revealed that access to finance helps substantially reduce poverty (Hassan & Sanchez 2009 [51] ; Dunford, 2006 [41] ; Littlefield, Morduch, & Hashemi, 2003 [42] ).

![]()

Table 1. Analysis of responses (SMES and MFIS).

Source: Designed by researchers (March 2023).

Source: Designed by researchers (March 2023).

Figure 1. Impact of MFIS on SMES.

R.Q 2: What is the volume of loans granted by MFIs to SMEs?

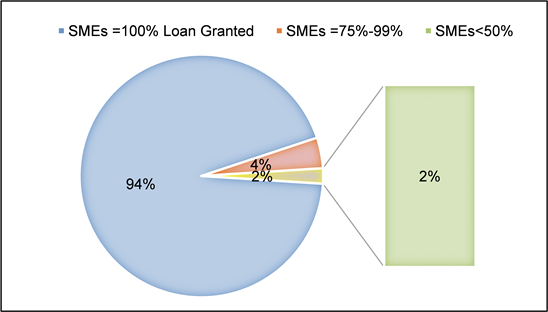

The study shows that the majority of SMEs are granted the total amount they applied for. Ninety-four percent (94%) of the studied sample were granted exactly 100% of the loan they applied for while 4 percent of the SMEs also being granted between 75% - 99% of the loan and the reminding 2 percent of the total sample was given less than 50% of the loan they applied for. The analysis of access to MFIs by SMEs is further shown in Figure 2. However, the general response from the beneficiaries shows a period of uncertainty in the granting of loan facilities.

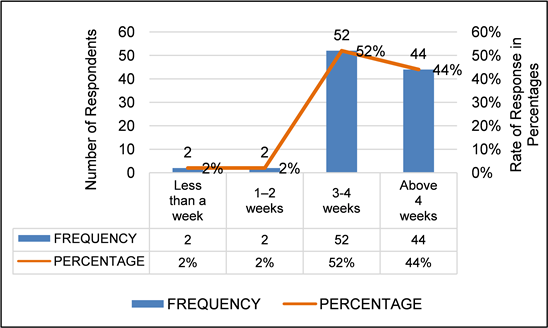

The preceding statistics on the volume of loans granted though encouraging did not point out the actual time taken before these loans applied for are granted. As shown in Table 2 indicates the time taken to access loans at MFIs. Analysis of Table 2 indicates that 2% of beneficiaries take between 2 - 3 weeks to access loans from the MFIs, while 52% percent takes 3 - 4 weeks, 2% percent takes 1 - 2 weeks and 44% percent takes more than 4 weeks to access credit facility from the MFIs. (Figure 3) Evidently, none of the respondents take less than a week to access credit facilities from the MFIs; this may be due to the documentation and authentication of documents associated with accessing credit facilities. However, Hassan & Sanchez (2009) [51] revealed that providing microfinance is associated with high transaction and information costs, and this may be the reason for the delay experienced by SMEs in accessing MFIs but this may require future research.

This study investigated the Customers Level of Satisfaction of SMES in accessing MFIs as it is a perennial problem why Microfinance institutions can lose their customers if their needs are not satisfied (Alaoui & Tkiouat 2019 [52] ; Kanyurhi 2013 [53] ) and these needs can be achieved when perceived quality surpasses customers’ expectations (Parasuraman & Zeithaml 1985) [54] . Customer

Source: Designed by researcher (March 2023).

Figure 2. Volume of loan granted.

Source: Designed by researchers (March 2023).

Figure 3. Access to MFIs credit.

Source: Designed by researchers (March 2023).

satisfaction is considered a key performance indicator and can help MFIs institutions achieve an edge in the market and, thus institutions should be sensitive to how they design the appropriate products and services, as well as the efficiency and effectiveness involved in creating the appropriate products and services (Alaoui & Tkiouat, 2019 [52] , Kralikova, 2015 [55] ; Wright, 2004 [56] ).

According to Alaoui & Tkiouat (2019) [52] , product design should revolve around the following factors:

・ Customer satisfaction is more sensitive to loan conditions than to the quality of service.

・ The incentive system has the strongest impact on service quality.

・ Credit analysis has the strongest impact on loan conditions.

・ Staff training has the strongest impact on staff competencies.

・ The staff competencies have the strongest impact on both product design and market research.

・ The customer’s visit has the strongest impact on the credit analysis

On the other hand, customer satisfaction is significantly related to customers’ experiences and motivations such as the primary reason for associating with MFIs, and the size of credit they seek (Agyei-Boapeah et al., 2020) [57] .

When respondents were asked about their expectations before transacting with MFIs, it became known that each respondent has his/her own expectations in accessing microfinance and their expectations are as follows:

・ To access prompt credit

・ To be assured of getting credit on time and as and when needed

・ To access more funds to expand their business

・ To receive support such as management training and accounting skills to manage their businesses

Figure 4 below shows 68% of customers’ expectations were met, with 9 percent not having their expectations met. The remaining percentage (23%) could

![]() Source: Designed by researcher (March 2023).

Source: Designed by researcher (March 2023).

Figure 4. Met/Unmet/Unknown SMEs level of satisfaction.

hardly tell whether expectations were met or not. Although 68% of customers’ needs were satisfied indicates customer satisfaction was above average and this required an investigation otherwise it is inevitable that the microfinance institution will lose their customers the reason for 22% of the respondent not being able to explain whether their needs were met also required an investigation.

R.Q 3: What are the challenges SMEs in assessing Micro-Credit?

The accessibility to credit facilities was predominantly found in accessing short term with a 54% rating whereas 44% of the respondents indicated they wanted to have a medium-term credit facility from the MFIs and 2 percent requested long-term credit facilities. The majority of the respondents have been successful in almost all of the loans they have applied for. Short-term credits dominate in MFIs, however, microfinance finds it very risky to offer medium and long-term credit as loan defaults are likely to be higher with such facilities. In addition, the need for short-term credits is driven by the fact that most SMEs use their loans to finance recurrent expenditures incurred in the day-to-today running of their business. The access to MFIs through the Munafa Fund even though quite remarkable has numerous challenges which mostly discourage SMEs from accessing credit when the need arises. Available data from the various respondents brought to the fore several challenges they face in accessing the loans. These challenges were categorized into: Delays in Loan Processing, Entire Process being Cumbersome, and Required Collateral displayed in Figure 5. As shown, 55% of respondents had issues with delays in the processing of loans by MFIs with regard to duration which can linger from several weeks into months. The findings also showed that 35% of respondents saw the entire process as quite cumbersome owing to the numerous documentation and other clerical processes SMEs needs to pass through before securing the facility. The remaining ten percent (10%) had difficulty in securing the required collateral.

As common to many schemes, especially with respect to financial institutions, accessing credit facilities come with its own challenges that impede the process

![]() Source: Designed By Researchers (March 2023).

Source: Designed By Researchers (March 2023).

Figure 5. Challenges faced by SMES.

and hinder the full potential of utilization of credits granted however, if such challenges are not addressed considering the sensitivity to how microfinance institutions design their appropriate products and services, as well as the efficiency and effectiveness involved in creating the appropriate products and services (Alaoui & Tkiouat 2019 [52] , Kralikova 2015 [55] ; Wright, 2004 [56] ) the microfinance institutions can lose their customers if their needs are not satisfied (Alaoui & Tkiouat 2019 [52] ; Kanyurhi 2013 [53] ).

R.Q 4: What is the rate at which SMEs borrow from MFIs as against other sources of capital?

SMEs need credit for varied purposes this could either be for business expansion or credit obtained used for other purposes rather than for business expansion. The issue of credit requests and intended purposes received varied responses from SMEs as some needed recapitalization as often as possible. As indicated in Table 3, the research pointed out that 58 percent of respondents did not often need loans as compared to 34 percent who often required loans. The minority consists of 6 percent of respondents who require loans very often. This analysis gives credence to the fact that even though beneficiaries of MFIs do need credit most of the time for their business they do not apply for loans as many times as the need arises. Also, the researchers also found that SMEs hesitate in applying for credit as often as they need them due to the high interest rate associated with the facilities given to them and the difficulties they face in satisfying some prerequisites needed for the credit facility.

R.Q 5: How Efficient is the MUNAFA Fund in Supporting Small Businesses?

The study shows that the majority of the SMEs are gratified for the effectual support of having access to the Munafa Funds. Ninety-four percent (94%) of the SMEs outlined that the support of the Munafa Funds to their businesses has been highly efficient, studied sample was exactly 100% of the loan they applied for with 4 percent of the SMEs also agreeing that it has been efficient. Only 2 percent of the total sample said the support of the Munafa Funds is inefficient. Figure 6 gives an empirical justification for the support SMEs have received from the Munafa Funds.

In 2018, Entrepreneurs du Monde decided to start working in the poorest neighbourhoods of Freetown-Sierra Leone and then in outlying areas. It set up Munafa (“prosper” in several local languages), a social microfinance institution

![]()

Table 3. Rate at which credit is accessed.

Source: Designed by researcher (January 2023).

offering individual loans, a savings account and tailored training. This comprehensive support allows entrepreneurs to develop their businesses and income and improve their living conditions in a sustainable way. Thus, Figure 7 shows the pictorial evidence on the efficient of the Munafa Funds in supporting small business.

![]() Source: Designed by researchers (March 2023).

Source: Designed by researchers (March 2023).

Figure 6. Highly efficient/efficient/inefficient.

![]()

![]()

Figure 7. Pictorial evidence. Designed by (Munafa-Sierra-Leone-Formation.jpg).

Entrepreneurs form groups of 15 to 35 people. After series of initial training sessions, participants can obtain a first loan based on their financing needs and repayment capacity. No guarantor or deposit is required. Twice a month, the group meets with its facilitator. Participants make loan repayments, add to their savings accounts and take part in training in management/sales or on a social theme (education, health, rights, etc.) to strengthen their businesses and help their family and community to move forward on all levels.

On the issue of how credits are utilized for business purposes, respondents gave some indication of situations not relating to business for which credits acquired applied. Below are some of the most frequent purposes for which credits are applied for by some SMEs.

・ Payment of school fees

・ Funerals

・ Housing building project

Data relating to the usage of the loans also indicates to some extent, the non-usage of the credit acquired for the intended purposes, which amounts to misapplication. It became clear that 88 percent of SMEs always felt the need to acquire loans for other purposes, and literally use the loans specifically meant for business for other purposes as shown above. The responses show that 28 percent do not use exactly what they have acquired as loans for solely business use but rather used for settling other pressing social and family issues. Furthermore, the majority of the respondents conceded that the loans they acquire lead to an increase in their capital base for business operations. This shows that the operations of the MFIs lead to improvement in the daily activities of the beneficiaries. However, the non-usage of credit for its intended purpose largely which amounts to credit misappropriation. This is one of the major setbacks in the growth of SMEs as admitted by 40 SME operators. Due to this when respondents were asked to suggest ways by which misappropriation could be minimized or avoided, the following were some of the suggestions given:

・ Educating clients on the proper usage of loans by encouraging beneficiaries to use the credit for the intended purpose.

・ MFIs should increase their rate of inspection of the shops and the daily activities of their clients.

・ By investing in profit-generating businesses that have enough cash flow for repayment of loans given.

It is therefore essential to indicate that favourable structures should be put in place, beyond credit offers, to ensure that SMEs can generate enough income to cater to the needs of their households in order to minimize credit misappropriation.

6. Summary of Key Findings

6.1. Contribution of SMEs within Freetown Municipality

The contribution of the SME sector to the economy in terms of employment creation cannot go unnoticed. The various SME subsectors, such as Manufacturing, Service, Commerce, and others, all play an important role. Commerce, i.e. buying and selling, vastly dominates the SME sector (94%) according to this research. The research reveals that little investment is required to initiate and run such businesses in addition, they do not require any supervisory procedures. The research shows clearly that a large majority of the SMEs i.e. 72% in the Freetown Municipality area are operating at a Micro stage as they hire the services of six or fewer staff in their various businesses. The sector though with a huge potential for growth is however faced with a huge capital constraint. Micro Financial Institutions have come to surmount this money constraint by providing start-up capital, as most respondents indicated MFIs to be their chief source of start-up capital according to the research.

6.2. MFIS Contribution to the Business Activities of SMEs

The research findings establish the enormous contribution of Micro Finance Institutions (MFIs) to the growth of the SME sector to curb the issue of capital constraints since most SME entrepreneurs indicated they could not readily access credit from traditional banks. These contributions are enumerated as follows.

6.2.1. Better Access to Loans

In this research, it was indicated that about 99%loans requests of most SMEs were granted by the MFIs. Most of the SMEs were in the micro stage of operation and some were even newbies in the business, therefore, they required small loans also a lot of the SMEs dealt with more than a single MFI. These loans facilitated to increase in their capital base thus their businesses. MFIs have created an attractive platform that allows Microbusinesses to save the little income they earn on a daily basis with little cost. The savings accumulated are the basis for the number of loans to be granted. With this background, the habit of saving has been improved through such activities of MFIs.

6.2.2. Business, Financial, and Managerial Training

MFIs have provided support services for SMEs in the form of business, financial and managerial training. As most SMEs lack the requisite knowledge and some have little knowledge in financial management, this sort of training had beneficiaries make informed financial decisions. In addition, 86% of the respondents indicated that the general services offered by MFIs have had a progressive result on their various businesses of SMEs.

7. Challenges SMES to Access Loans

The research exposed some of the major challenges SMEs had to overcome in their bid to access meagre loans for their business as most respondents reiterated; these are delay in processing as most documents took a longer time than usual to process.

Cumbersome procedures had to be overcome as most entrepreneurs in this sector were semi-literates and so filling of loan application forms proved to be difficult. Some of the SME respondents find the process of accessing credit as cumbersome and the synopses of these challenges are:

・ In ability to provide the collateral securities in cases where they are demanded.

・ High interest rate was as mentioned as one of the challenges faced in accessing credit. The high interest rates in most cases make clients unable to repay their loans.

The MFIs on their part provided some of the challenges they also face in granting credit. These are:

Problem of repayment of loans:

・ Lack of collateral security required on the part of the SMEs

・ Poor records keeping on the part of the SMEs

・ Lack of transparency in the business accounts and related business information

・ Lack of proper documentation in terms of business registration and a permanent business address.

Credit Utilization Rates:

The research shows that 72% of SME respondents used the loans for the intended purpose and this brought about a major growth in the SME sector. It also stabilizes the operations of the MFIs for progress and better services. However, 28% of respondents misapplied the loans, which meant inability to achieve growth in business. This misapplication of business loans defeats the purpose of MFIs; in the worst case clients would be unable to repay loans there by causes a steady rise in loan percentage default and the need for collateral securities for even meagre loan requests.

8. Conclusion and Recommendations

The research on the impact of MFIs on SMEs revealed an upsurge of Micro Finance Institutions within the Freetown municipality, which proved very progressive, notwithstanding the associated challenges. It is worth noting that the operations of MFIs have curbed the major challenge of the SME sector to a very large extent such as ready access to loans. The research findings also show that the MFIs have contributed to the development of SMEs through the delivery of non-financial service such as Business, Financial and Managerial training programs. Microfinance Institutions have largely established and developed the area of revenue mobilization with their saving schemes which have brought savings to the doorsteps of the clients, the readiness to receive meagre amounts on a daily basis and above all less costly. This has enhanced the savings habit of the sector as little revenue recipients who were unable to save with the commercial or traditional banks are offered a big opportunity to save. This has aided in reinvestment of the capital saved. It is also worth mentioning that MFIs provide better access to loans than the traditional banks to the poor. As the upsurges of MFIs in Freetown Municipality have improved the activities of SMEs tremendously, the research reveals however that MFIs are faced with a few challenges that can undermine their purpose of making loans easily accessible to SMEs. It is worth highlighting these challenges. The research shows that a good number of MFIs required collateral security before loans are granted and this has an adverse effect on SMEs as some are unable to provide the collateral requested. Some members of the SME sector misappropriated their loans for non-business purposes. In the midst of these challenges, the research SMEs within Freetown Municipality has tremendously progress as the sector and has provided entrepreneurs with solid financial support.

We proffer the following recommendations to improve the service of MFIs within Freetown Municipality and also sustain the progress and improve the growth of the SME sector.

The growth of SMEs does not only rely on access to loans but also on the creation of favourable and formidable business environment

The MFIs have a great responsibility of making sure that proper use of loans for the purposes intended as that facilitates business acceleration. This can be achieved by making credits or loans client-oriented and not product-oriented.

Also, appropriate and widespread monitoring activities should be provided for clients who are granted loans to sustain MFI operations and enhance the growth of SMEs.

The MFIs could be swift to measure check successes by considering factors like high rates of loan repayment, client outreach, and financial sustainability, however, these cannot be considered a success if these activities are not replicated in the progress of the SMEs.

The Micro Finance Institutions can research out very profitable business lines and grant loans to clients who have the capacity to capitalize on such business lines in order to reduce default rates.

The MFIs provide business and financial training on a regular basis and in most cases tailor-made toward the training requirements of their clientele.

In addition, recommendations for the future researcher are: an investigation into the default of Microfinance Loan in Sierra Leone; an exploratory research on the slow processing of microfinance and its impact on SMEs.

Research Ethics

There are no foreseen ethical issues involved in this research.