Integrating Curriculum Design Theory into ESP Course Construction: Aviation English for Aircraft Engineering ()

1. Introduction

English for Specific Purposes (ESP) teaching and research started in the 1960s and ’70s in China, but developed quickly over the past decades. This is because of the fact that all trades and professions need composite talents who have not only a good grasp of English skills, but also a conscious command of professional or field knowledge. In aviation, English has long been generally accepted as the de facto medium of communication. This is especially true in international airports and airlines. Chinese EFL (English as a foreign language) learners are well motivated and particularly interested in ESP. The boom in ESP teaching, in both college education and continuing education, is a natural result of the growing societal demand for English skills, the rapid development of the field of applied linguistics, and advances in educational psychology. In this context of rapid growth, ESP teaching definitely needs to develop its own methodology and curriculum separate from those of general ESL learning, because it has different objectives, content target learners, and goals than the broader field.

Designing an English language curriculum is of especially importance for ESP instructors. According to Nunan (1993), the teacher can only fulfill his or her responsibility to develop strong curriculum material if given the time, the skills and support to do so. While the support may come in the form of curriculum models and guidelines, it may also include companies (in the aviation context, which will be assumed henceforth, airlines and other companies involved in the aviation industry) that need English language training for staff and require individuals who can act in a curriculum advisory position.

Such support must not be seen as existing in isolation from the curriculum. The key issues in ESP curriculum design are 1) fostering the ability to communicate successfully in occupational settings; 2) balancing content language acquisition and general language acquisition; 3) designing materials that will work in both heterogeneous and homogenous learner groups; and 4) developing materials (Nunan, 1987: p. 75).

2. ESP Curriculum Design in the Chinese Context

In the Chinese context, curriculum or course design and construction need to consider a wide range of factors: the learners’ background, their present knowledge and lacks, the duration of the learning period, learner expectations, the knowledge and skill of the teachers, the curriculum designer’s strengths and limitations, and the principles of teaching and learning. In this paper, these factors are analyzed in three sub-processes: environment analysis, needs analysis and the application of principles. Teaching English as a Foreign Language (TEFL) is an activity with a significant history at various levels of education in China, and TEFL methodologies and pedagogy are well developed and have been extensively applied. However, as an English Language Teaching (ELT) activity ESP curriculum design definitely needs to be conducted in a way that reflects the unique characteristics of this activity.

2.1. Environment Analysis

The Sino-European Institute of Aviation Engineering (SIAE) was jointly setup in 2007 as a joint effort of the Civil Aviation University of China (CAUC) in Tianjin and four of French aviation colleges: GEA (Groupement des écoles d’aéronautique), ENSMA (École nationale supérieure de mécanique et d’aérotechnique), ENAC (École nationale de l’aviation civile), and ISAE (Institut supérieur de l’aéronautique et de l’espace). SIAE represents an attempt to train local aviation engineers in a multicultural environment, and also to bring the benefits of the French engineer training system to China and train Chinese aviation engineers to expand their knowledge and capabilities. Hundreds of students have been enrolled at SIAE since its establishment. Three majors are offered: aircraft structure and materials, operation and maintenance of propulsion systems, and electronic systems and on-board equipment. The working language in the classroom is mainly English with Chinese and French as auxiliary languages.

It was originally hoped that SIAE students would receive an engineering diploma after six years of study― three years of preparatory courses and three years of engineer training. This introductory and professional training is undertaken by professors from both Chinese and French universities and experts from European aviation enterprises. The education resources and models used by the French engineer training system are introduced to provide effective education and meet the increasing need for senior aviation engineers in China.

Students at SIAE are an academic elite selected from among first-year students at CAUC if their marks on college entrance exam are above a certain line. They take an English test to get admission to SIAE, and are on or above the intermediate level in English fluency as they begin their ESP course.

2.2. Needs Analysis

“Needs analysis is the cornerstone of ESP” and its proper application should result in a “focused course” (Dudley-Evans & St John, 1998: p. 121). By “focused course” we mean that more attention is given to the design and construction of it and that related departments will coordinate and cooperate for the preparation of it. Based on the curriculum design process of Nation & Macalister (See Figure 1), an attempt is made here to adopt a framework

for ESP course design that employs needs analysis as its starting point, aiming―in the processes of curriculum development, course design, and evaluation of the effectiveness and efficiency of implementing the needs-based course―to highlight the expectations of Chinese authorities, of the customers of the aviation companies and of the learners themselves. Room still exists for CAUC to improve the present curriculum framework. Feedbacks show that students expect longer time to express themselves for aircraft engineering purposes. The revision of the existing ESP curriculum seems extremely timely; in fact, opting for curriculum renewal periodically can be invaluable in the attempt to ensure that a course remains aligned with the learners’ needs (Jackson, 2005). In quest of better solutions to this issue, the role of needs analysis in any ESP curriculum should not be underestimated (Munby, 1978; Hutchinson & Waters, 1987; Robinson, 1991; Flowerdew & Peacock, 2001; Hamp-Lyons, 2001).

Learners’ needs can be divided into necessities, lacks and wants. In our present context, we can discover each of these by a variety of means: by testing; questioning and interviewing; recalling previous performance; consulting employers, teachers and others involved; collecting materials such as textbooks and manuals that the learners will have to read and analyzing; and investigating the situations where the learners will need to use English. The best and most practical way to design an ESP course is to base it on what the learners’ request. Below is an extensive but not necessarily exhaustive list of some of the main areas where the engineers may need to make use of their English language skills in professional life.

• Reading technical manuals in English;

• Reading journals in the fields of aeronautics, electronics, information technology, business, and so on;

• Writing and reading a wide variety of emails, faxes, letters and other professional communications;

• Writing CVs;

• Writing formal reports;

• Receiving foreign visitors and engaging in both informal and informal communication;

• Telephone conversations of both a technical and a commercial nature;

• Attending meetings;

• Negotiating new business or contracts for the company;

• Overseas travel;

• Giving formal presentations and responding to questions;

• Attending international conferences.

Obviously some of these items will be more or less important for learners depending on the exact nature of the career path they follow. However, to be as “practical” as possible it is advisable for students to develop language skills equal to communication in all the above contexts. This is the aim of the first year English program at SIAE. The program is intended to provide learners with a wide range of English skills, including reading, writing, listening, and speaking skills, appropriate to various professional situations.

2.3. The Application of Principles

2.3.1. Content Difficulty

The difficulty of the English content these learners are exposed to should reflect the level and focus of their normal courses. College students in aircraft engineering are not studying middle school English or English for general purposes. They need university-level content, and content that is tailored to the field and their future needs and goals. This means that the ESP instructor must be not only skilled in the English language, but also familiar to a certain extent with aircraft technology or at least the content of a good, relevant text. The instructor needs to be able to explain or translate quite a number of terms in this field, knowing that most of the students will be familiar with the concepts under their Chinese names. Therefore, while language skill is one thing to an ESP instructor and content familiarity is quite another, yet in this context it is necessary.

2.3.2. ESP Curriculum Design

Curriculum must be content-rich and useful to the students stretching their area knowledge in its own right. This does not mean that the texts used always need to be complicated: rather, they need to be balanced, providing not only plenty of language points and key words and expressions for general English, but also specialized terminology for the aviation industry.

2.3.3. Classification of Aviation English as an ESP Course

Exercises intended to increase knowledge of the material should be correct and authentic, with regard to the information they present on both the aviation industry and the English language, as well as the way they present it. This means an end to trivial tasks such as in-class games or discussions, and a major shift to focus on real-world comprehension, inference, and debating. Tasks should not only review and reinforce students’ area knowledge, but also stimulate students’ desire for more information.

In general, aviation English can be defined as a comprehensive but specialized subset of English related broadly to aviation, including the “plain” language used for radiotelephony communications when technical or jargonistic phraseology does not suffice. Not restricted to controller and pilot communications, aviation English can also include the use of English relating to any other aspect of aviation: the language needed by pilots for briefings, announcements, and flight deck communication; the language used by aircraft engineers, flight attendants, dispatchers, managers and officials within the aviation industry; or even the English studied by students themselves, in aeronautical and/or aviation universities and programs. Aviation English can be seen as a subdivision of ESP, of the same kind as business English; and English for aircraft engineering, to be very specific, is a subset of aviation English as an ESP course. The diagram (See Figure 2) may help the reader to understand the further subdivisions that can be applied to aviation English as an ESP course:

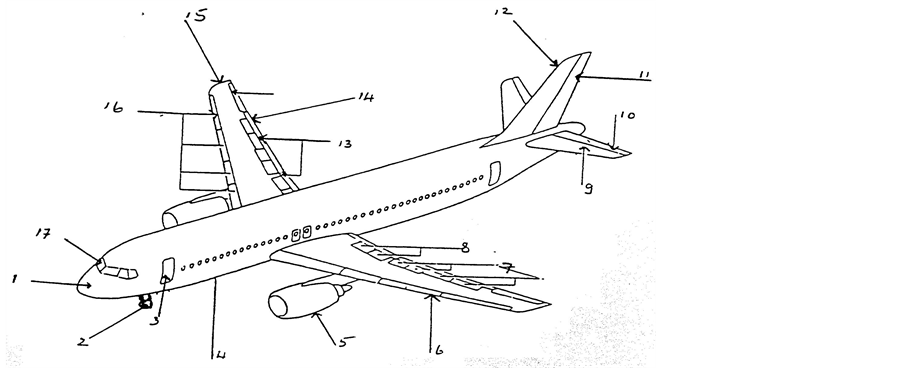

Research on language teaching and learning should be used to guide decisions on curriculum design and content selection, in this as other L2 fields. A very large body of research has been conducted on the nature of language and language acquisition, which can guide practitioners’ choices regarding what to teach and how to sequence it (Diaz-Rico, 2008; Greenberg, 2004). The principles that can be derived from this research include the importance of graphic teaching and direct teaching, repetition and thoughtful processing of material, taking account of individual differences and learning styles, and learner attitudes and motivation. The latter will be strong and have a positive effect on learning if the learner has a clear, conscious purpose for learning English. For example, a course for maintenance staffs could focus on fuselage constructions and the names for parts of aircraft systems (See Figure 3) that they will need to know in English.

2.3.4. A Case Example of Aviation English Class Activities

Awareness of class activities is an important part of curriculum design. During the development of the curriculum materials, ESP instructors should be able to foresee how their lectures and class activities will be planned

Figure 2. Subdivision of aviation English as an ESP course1.

1. radome; 2. landing gear; 3. door; 4. fuselage; 5. nacelle; 6. leading edge; 7. spoilers; 8. speedbrakes; 9. tailplane; 10. elevator; 11. rudder; 12. fin; 13. flaps; 14. trailing edge; 15. wing tip; 16. slats; 17. windshield.

Figure 3. Parts of an airplane.

and organized. Take the Figure 3, for example. For a class covering the vocabulary in the figure, a teacher might plan and develop teaching material as follows:

Task: Students will be required to read through their part of the text, making sure they understand the underlined vocabulary and how the words are pronounced. Each of them will then explain the structure and purpose of the component they have just read about to the group.

Student A: The modern aircraft has five basic structural components: fuselage, wings, empennage (tail structures), power plant (propulsion system), and undercarriage. Fuselage: The word fuselage is based on the French word fuseler, which means “to streamline”. The fuselage must be strong and streamlined, since it must withstand the forces that are created in flight. According to its arrangement, the fuselage is the main body structure to which all other components are attached. It contains the cockpit or flight deck, passenger compartment, and cargo compartment. While the wings produce most of the lift, the fuselage also produces a little lift. A bulky fuselage can also produce a lot of drag. For this reason, the fuselage is streamlined to decrease the drag. We usually think of a streamlined car as being sleek and compact―it does not present a bulky obstacle to the oncoming wind. A streamlined fuselage has the same attributes. It has a sharp or rounded nose with a sleek, tapered body, so that the air can flow smoothly around it.

Student B: Wings: The wings (See Figure 4) are the most important part of the aircraft for producing lift. Wings vary in design depending upon the aircraft’s type and purpose. Most airplanes are designed so that the outer tips of the wings are higher than where the wings attach to the fuselage. This upward angle is called the dihedral and helps keep the airplane from rolling unexpectedly during flight. The wings also carry the fuel for the airplane.

Student C. Tail structures: The empennage or tail assembly provides stability and control for the aircraft. The empennage is composed of two main parts: the vertical stabilizer (fin), to which the rudder is attached, and the horizontal stabilizer, to which the elevators are attached. These stabilizers help keep the airplane pointed into the wind. When the tail end of the airplane tries to swing to either side, the wind pushes against the tail surfaces, returning it to its proper place. The rudder and elevators allow the pilot to control the yaw and pitch motion of the airplane, respectively.

Students D and E will go on explaining the other parts of the aircraft, such as “landing gear” and “flight controls (See Table 1)”.

It is very important that curriculum designers make the connection between language learning theory and the practice of designing lessons and courses. In the case of this English course for aircraft engineering, we listed important terms together so that students could compare these words and better remember them, along with their definitions and functions:

The curriculum design model in Figure 1 has “Goals” as its center. This is because it is essential to decide why a course is being taught and what the learners need to get from it. Goals can be expressed in general terms and be given more detail later on, when considering the content of the course.

3. Content Arrangement for Improvement of Students’ Language Skills

3.1. Course Planning

A group needs analysis will be made at the beginning of each course, and sessions will be planned according to participants’ methodological awareness and aviation background. As far as teaching methodology is concerned, the following areas should be considered before adopting a methodology:

• Task design;

• Phonology (focusing on the discrimination and production of English sounds and their differences from those of Chinese and French, as students also learn French as a foreign language);

• Listening skills (for gist, specific information, and inference);

• Daily English for aircraft engineers;

• Using DVD materials or video clips to improve comprehension and language skills;

• Sourcing, creating, and exploiting teaching materials presenting the concepts and terminology of aircraft engineering;

• Teaching and learning evaluation.

Aviation English for aircraft engineering may cover areas such as aircraft structures and systems, airport layout, flight operations and flight safety, standard and nonstandard phraseology and terminology, and/or incidents and accidents. The balance of course content may reflect the needs and backgrounds of the participants.

Specific materials, for example, from manuals on regional aircraft, helicopters, engine components, fuel systems, aircraft reconfigurations such as cargo conversions, or complex avionics integration projects, should be employed in language teaching for aircraft engineering.

3.2. Modules

3.2.1. Time Allocation

At SIAE, the ratio of time provided for instruction in aviation English to that for general English is about 1 to 4. In order to improve aircraft engineering students’ language ability, however, we are designing a course with a down-to-earth time allocation (See

Table 2).

The learners have indicated that they desire more opportunity to interact with their ESP instructor, in addition to attending general English class. Recent experiences show that students of aircraft engineering are highly motivated to attend ESP class, meaning that more time should be devoted to it.

3.2.2. Language Skills

The key skills needed to function in a language in a professional engineering context include grammar, pronunciation, listening, speaking and technical writing. This part of the course is intended to consolidate students’ awareness and mastery of English structure and grammar, with a special focus on PSI (pronunciation, stress and intonation). To develop and improve their spoken language skills, students are encouraged to participate in conversations on various subjects related to everyday life, both in classroom discussion and in formal debates, using vocabulary from aeronautical engineering. To improve their technical writing skills, students are taught both formal and informal expressions and ways of communicating.

3.2.3. ESP Knowledge

Students of aircraft engineering may acquire ESP knowledge via the Introduction to Aeronautical English. This book provides students with a basic, core English vocabulary for exploring the world of civil aviation, and allows them to develop their comprehension of written and spoken English in a context suffused with knowledge of aircraft engineering. The four major themes are aviation history, aircraft structure, aerodynamics, and the airport environment.

3.3. Placement and Advancement in the Program

All 100 participants chosen by SIAE were assigned a learning level (intermediate, or high intermediate) based on their performance in the Admission English Test, which is a standardized test normally administered, scored, and analyzed by ESP instructors at SIAE. They were put into four groups on the basis of the scores they got in the Admission English Test: Classes A, B, C, and D.

Other specially prepared diagnostic tests were used after learners were placed in their classes to test their mastery of various language skills. Learners must demonstrate that they have successfully met the instructional objectives set for the current level and achieve a certain TOEFL score before they can complete their study in China and go to France for further education. Exit examinations are also administered: these are achievement tests designed by the ESP teachers in order to measure learning outcomes.

3.4. Learner Evaluation

In addition to traditional achievement tests and quizzes, learner progress is also measured with alternative forms of assessment that are more qualitative in nature, such as portfolios, focused observations using checklists, self Table 2. Time allocation for an aviation English course.

Table 3. Summary of global grading.

and peer assessment, interviews, projects, oral presentations, and evaluation of conference presentation. Tests take place in the last week of the module following the one being tested. Each of the first two averages will count for 25% of the global grade (See Table 3).

4. Conclusion

This paper has discussed the definitions of ESP, addressed the relationship between aviation English and ESP, and explored aviation English curriculum design and the organization of materials in the Chinese context. Next, a case of this illustrative and communicative approach to teaching aviation English is considered. The content of the paper was based on both authors’ professional experience as ESP and ELT instructors designing and delivering content-based language programs in aviation linguistics and Aviation English for engineers at CAUC. Where possible, these issues have been discussed in the light of pertinent current academic literature. We hope that the discussion in this paper can provide some insights into the challenges facing ELT instructors acting as ESP curriculum developers whether in China or elsewhere in the world.

NOTES

*The publication of this paper is a partial fulfillment of the program: 2012ZD39.

1Note: ELT―English Language Teaching; EMT―English as a Mother Tongue; EFL―English as a Foreign Language; ESL―English as a Second Language; ESP―English for Specific Purposes; EGP―English for General Purposes; EOP―English for Occupational Purposes; EST―English for Science and Technology.