Incidence of Urinary Tract Infections and Its Aetiological Agents among Pregnant Women in Karnataka Region ()

1. Introduction

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are the second most common infections in community practise. Incidence of UTI is higher in women than men, 40% to 50% of whom will suffer at least one clinical episode during their lifetime [1]. The increase risk factor for UTI in women may be due to short urethra, absence of prostatic secretions, pregnancy and easy contamination of urinary tract with faecal flora [2]. Approximately 90% of pregnant women develop ureteral dilation, which will persist until delivery [3]. And it may contribute to increased urinary stasis and ureterovesical reflux. Additionally, the physiological increase in plasma volume during pregnancy decreases urine concentration and up to 70% of pregnant women develop glycosuria, which is considered to encourage bacterial growth in the urine [3,4]. Thus UTIs are the most common bacterial infections during pregnancy, with pyelonephritis being the most common severe bacterial infections complicating pregnancy. Among the pregnant women approximately 4% to 10% will have asymptomatic bacteriuria (ASB), and 1% to 4% will develop acute cystitis and 1% to 2% may develop severe acute pyelonephritis during the second half of pregnancy [5].

Women with a history of UTIs are at increased risk of having a UTI during pregnancy and other risk factors for UTIs during pregnancy include lower socio economic status, individual hygiene, sickle cell trait and anaemia, increased parity or age, and lack of prenatal care. The functional urinary tract abnormalities and diabetes mellitus can also increase susceptibility to UTIs during pregnancy [6].

Infections, particularly in pregnancy and in elderly may be asymptomatic, if the UTIs are untreated during pregnancy, it increases 20% to 40% elevated risk for pyelonephritis, premature delivery, and fetal mortality, ASB doubles the risk of preterm labor and/or low birth weight. UTIs during 3rd trimester increase the relative risk for mental retardation or developmental delay, as well as fetal death [6].

The members of family Enterobacteriaceae, are the most frequent pathogens detected, causing 84.3% of the UTIs [7]. The organisms causing UTIs during pregnancy are the same as those found in non pregnant patients. E. coli accounts for 80% - 90% infections [8], about 85% of community acquired UTIs, 50% of nosocomial UTIs and more than 80% of uncomplicated pyelonephritis [9]. These E. coli may be endogenous flora of the colon, first colonize the periurethral area and vaginal introitus, then ascend to the bladder and from the bladder to the renal pelvis by receptor mediated ascending process. The process involves both host and bacterial factors, namely tissue receptors and expression of bacterial attachment factors [10]. A vacuolating cytotoxin expressed by uropathogenic E. coli, elicits defined damage to kidney epithelium [11]. The medically equal important enterobacteriaceae genus Klebsiella accounts for 6% to 17% of all nosocomial UTIs and shows an even higher incidence in specific groups of patients at risk [12]. Proteus mirabilis is a common cause of UTI in individuals with long term urinary catheters in place or individuals with complicated UTIs. P. mirabilis despite its antibiotic sensitivity can be difficult to clear by antibiotic treatment. It has been hypothesised that bacteria within a stone matrix are protected by antibiotic treatment [13]. Some UTIs are caused by other less common types of bacteria [14].

Therefore, physiological, hormonal and anatomical change during the pregnancy leads to express different types of receptors in the urinary tract which enhances the specificity of infection. It has been demonstrated that the untreated asymptomatic bacteriuria increased the frequency of premature delivery and neonates with low birth weight [15] and it was also likely to cause acute pyelonephritis at a rate of 20% to 30% [14,16,17]. Thus it is important to identify UTI infections by aggressive screening and treatment for ASB during pregnancy which is essential to avoid such complications. This study focuses on the detection and incidence of UTI among pregnant women of Southern and Northern parts of Karnataka, South India. It also focuses on the incidence, types of etiological agents at different periods of pregnancy.

2. Materials and Methods

The study was conducted on the pregnant women suspected with UTI attending outpatient departments of Govt and Private hospitals/clinics and pathological laboratories in Gulbarga, Belgaum and Bangalore cities of Karnataka, South India. The samples were collected from December 2009 to August 2010. Freshly voided midstream urine sample were collected in a sterile wide mouth container from the individuals preliminary routine urine tests positive for pus cells and albumin. All the urine samples were processed within one hour after the collection for aerobic bacterial culture. If delayed, samples were refrigerated and processed within 4 - 6 hours. Over all 417 urine samples were collected from the women with different stages of pregnancy. All chemicals required for culture media and reagents were procured from HiMedia laboratories Pvt Ltd., Mumbai.

2.1. Microscopic Study

One of the diagnosis criteria of UTI was based on microscopic findings of more than 10 pus cells/ high power field (40×) in urine were included in the study.

2.2. Isolation and Identification of Uropathogens

Semiquantitative urine culture using a calibrated loop was used to isolate bacterial pathogens on nutrient agar plates. Isolated colonies were further characterised based on cultural characteristics by growing on differential media, such as MacConkeys agar and blood agar [18]. Following the recommendations of Kass [19] in distinguishing genuine infection from contamination, culture of a single bacterial species from urine sample at a concentration of >105 CFU/ml. Only a single positive culture per patient was included in the analysis.

The plates were incubated at 37˚C for 24 hrs and extended to 48 hrs in culture (growth) negative cases. Further, the isolates were identified by cultural, morphological and biochemical tests. The method used in the identification and characterisation of isolated bacteria included Gram staining, motility test and biochemical tests like, TSI and IMViC according to Cheesbrough [20,21]. Isolated and characterized uropathogens were then preserved in nutrient broth containing 25% glycerol at −20˚C.

3. Results

Of the 417 urine samples examined in this study, 206 were found to contain significant bacteriuria. Urine microscopy revealed >10 pus cells/high power (40×) field. Overall incidence of UTI in pregnant women was found to be 49.4%.

Overall incidence of UTI in relation to age ranged from 44% to 53%, women in the age groups 21 - 25 and 36 - 40 years showed highest incidence (53%) respectively (Table 1).

Based on parity (number of pregnancy), women in their 3rd and above pregnancy had a greater number of UTI (54.8%), followed by first pregnancy (48.4%) and the lowest incidence of UTI (43.3%) was seen in the second pregnancy (Table 2).

The prevalence of UTI by gestational age (age of pregnancy) is lowest in 3rd month (25%) followed by 29% in 5th month and highest of 70.2% in 7th month of pregnancy (Table 3). While, the incidence of UTI by trimester as shown in Table 4, women in their 3rd and 2nd trimester had a greater number of UTI cases having an

Table 1. Incidence of UTI in relation to age distribution in pregnant women.

Table 2. Incidence of UTI by parity (no: of pregnancy).

Table 3. Incidence of UTI by gestational age (age of pregnancy).

Table 4. Incidence of UTI by trimester period.

incidence of 54.1% and 43.3% respectively than in the first trimester (25%).

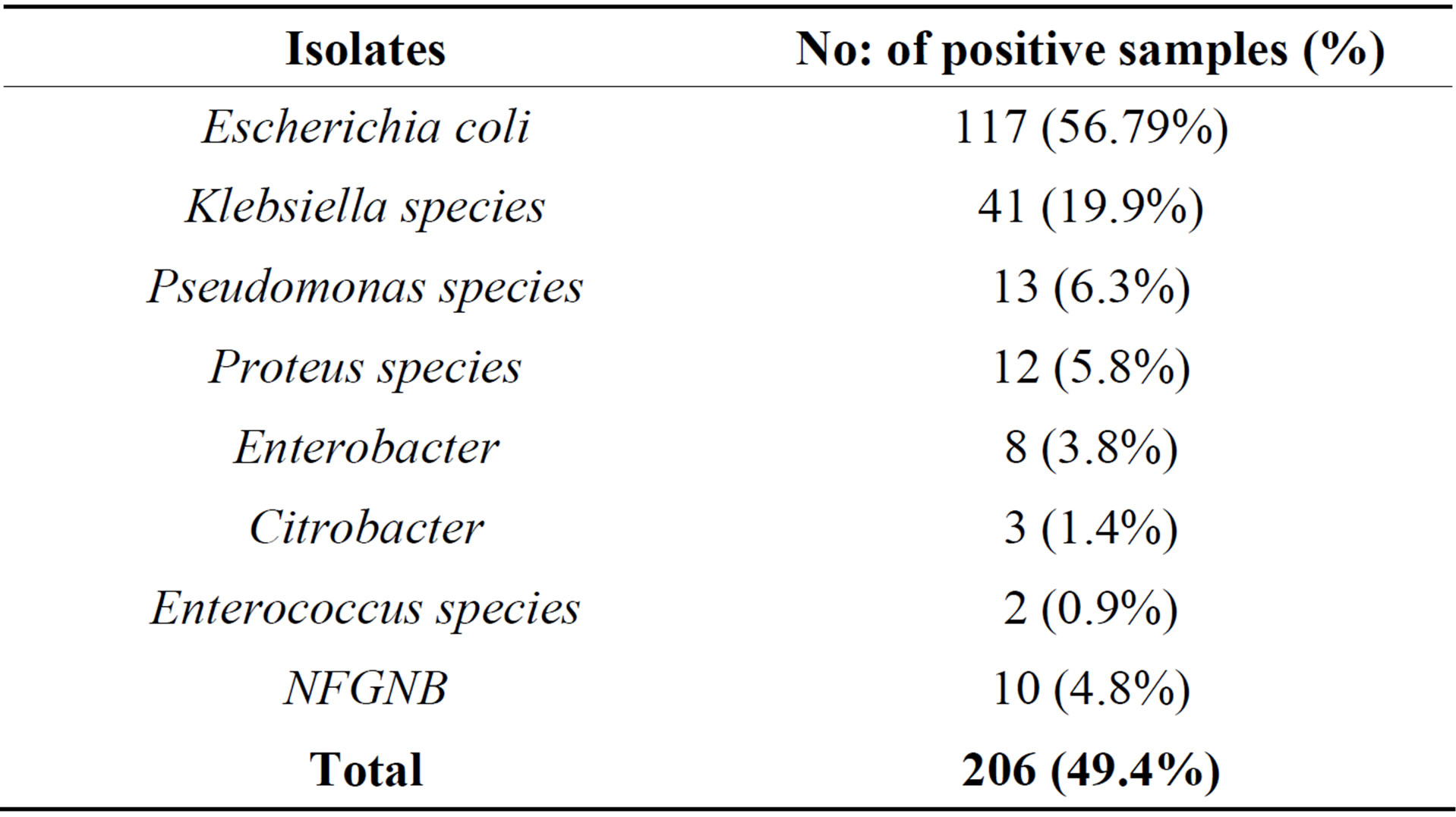

Among 206 bacterial isolates obtained from 417 urine samples, majority of the isolates (99%) were Gram negative bacteria which included Escherichia coli (56.79%), Klebsiella sps (19.9%), Pseudomonas sps (6.3%), Proteus sps (5.8%), Enterobacter sps (3.8%), Citrobacter sps (1.4%), Enterococcus sps (0.9%), and other NFGNB (4.8%) as shown in Table 5.

The frequency of isolation of different organisms was found to be similar with respect to the age of pregnancy and age of pregnant women (Tables 6 and 7).

4. Discussion

Bacteriuria, either symptomatic or asymptomatic, is common in pregnancy. If left untreated; 20% - 30% of asymptomatic bacteruria will lead to acute pyelonephritis. This may result in low birth weight of infants, premature delivery cases and occasionally, stillbirth, so it is a serious threat for the mother and foetus [22]. UTIs during pregnancy may increase the risk of cerebral palsy or mental retardation. Therefore, careful monitoring of the UTI infections among pregnant women becomes necessary [6].

Pregnant women are more susceptible to UTI because of increased urinary content of amino acids, vitamins, and other nutrients, which encourage the persistence of infection [23]. Physiological increase in plasma volume during pregnancy decreases urine concentration and most of (70%) pregnant women develop glycosuria which is considered to encourage bacterial growth in urine [3]. In addition, some maternal defence mechanisms are less effective during pregnancy [24].

The incidence rate of UTIs in pregnant women in this study population was found to be 49.4% which is nearly to par with figures in Nigeria by Okonko et al., [25] who reported an incidence rate of 47.5% in pregnant women However, the prevalence rate of UTI has been reported to be comparatively less in other countries like 38% in Iran, 28.5% in Pakistan, 14.2% Saudi Arabia, 10.6% in Turkey, 30% from Yemen [26]. The finding of this study is lesser than the incidence rate of 58% and71.6% in a similar study among pregnant women in two different towns of Nigeria [27,28]. This may be due to poor personal and environmental hygiene, low socio economical status, lacked awareness of health care. Reports from India on the incidence of UTIs in the non pregnant women vary from 10% - 40%, from Aligarh 10.8% [29], 16.3% from Tamilnadu [30] and 40.4% from Imphal, Manipur [31].

Table 5. Frequency of bacteria isolated from pregnant women with UTI.

Table 6. Incidence of bacterial isolates in different trimester period.

NFGNB-Non fermentative gram negative bacilli.

Table 7. Frequency of bacterial isolates in UTI cases in relation to month of pregnancy.

This study also shows that 54.8% of women who had UTI were in their 3rd pregnancy and above with high incidence rate. Our results on incidence of UTI by parity revealed that the higher incidence was found in women who were in their 3rd pregnancy and above. Our results are almost comparable to the results reported by Okonko 2009 [25] from Nigeria, except in first pregnancy. So, parity is one of the possible factors affecting the prevalence and incidence rate of UTI among pregnant women.

Due to progressive obstruction of the urinary tract, it is expected that the highest frequency of UTIs is in 3rd trimester rather than 2nd and 1st trimester. This study reporting very less incidence of UTI among the women in there 1st trimester (25%) compared to the reports from Nigeria (42.5%) [25], however, it is slightly more when compared to reports from Yemen (17.1%) [26]. However, incidence rate of UTI in 2nd trimester (43.3%) and 3rd trimester (54.15%) of our study are comparable with reports from Nigeria by Okonko [25] and lower incidence was reported by Al Haddad 34.1% and 48.8% respectively [6]. From earlier reports and our own results revealed that more than 50% incidence of UTI in pregnant women occurs in the 6th and 7th month of there pregnancy. Our results regarding the age of infection, gestation and parity concur with the other reports [25,26]. Increased parity, age and gestational age increases the risk of UTI in pregnant women Mainly Gram negative bacteria belonging to Enterobacteriaceae were isolated from urine samples of pregnant women. The most predominant uropathogen was Escherichia coli accounting for 56.79% was seen in our study in comparison to most frequently isolated organism in Britain (65.1%) and in two US studies by Sahm et al., in 2001 [32]. This finding is similar to other reports which suggest that gram negative bacteria, particularly E. coli are the commonest pathogens isolated from patients with UTI [27,33]. The incidence of E. coli in our study was higher when compared with the Nigerian studies reporting 42.10% [25] and 51% [34]. Most of the studies conducted in Africa and Arab countries showed less than 50% isolation of E coli from the UTI patients but reported a higher percentage (29%) of S aureus as second most frequently isolated bacteria from UTI cases. Reports from other developing or developed countries were the isolation of Gram positive bacteria as uropathogen is very low <10% [29-31]. It is interesting to note that no single species of S aureus was isolated in this study however less than 1% of uropathogen belongs to Enterococcus sps.

The second commonest uropathogen isolated in our study was Klebsiella species (19.9%), Pseudomonas species (6.3%), Proteus sps (5.8%). This was similar to other studies [35-39]. Other pathogens isolated were Enterobacter (3.8%), Citrobacter (1.4%), Enterococcus sps (0.9%) and NFGNB (4.8%). In contrast to this finding, one study from Aurangabad showed Klebsiella as the most common isolate followed by Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus [40].

Our results agree with reports from research workers in other countries, with minor differences, which could be due to differences in the environment, social habits of the community, the standard of personnel hygiene and differences in health care [41-43].

5. Conclusion

UTI in pregnancy is associated with significant morbidity for both mother and baby. Our results revealed that higher incidence rate of UTI (49.4%) in pregnant women tested compared to other studies earlier reported may be due to the urine samples that were collected only from pregnant women with signs and symptoms of UTI. It was also observed that E. coli was the most frequently isolated organism, prevalence rate was higher in 3rd trimester and highest infection rate was observed in 7th month of pregnancy, concluding that old age pregnancy and increased parity are prone for UTI apart from individual hygiene and economical status. This study highlights the need to raise awareness of UTI and to expand services for prevention t of UTI during pregnancy by maintaining hygienic conditions.

NOTES