International Comparison of Intercity Differences in Premature Deaths: Pyll-Rates in Canada, Finland and Russia 2010 ()

Received 28 April 2016; accepted 12 June 2016; published 15 June 2016

1. Background

Internationally, different parameters describing mortality are used as indicators of health and measures for well- being [1] [2] of a population or its part. Total mortality rate of the population is the weighted average of the mortality of different age groups. Mortality rates are also used as a basis when counting average of expected length of life of a population. Internationally, the mortality statistics can be considered among the most comparable, although the procedures of registering and classifying mortality rates differ in different countries.

Potential years of life lost (PYLL) rate is used for reviewing time of death in relation to life expectancy [1] [3] . It is a sensitive way to describe premature deaths. PYLL-rates are calculated from death certificates or death registers. PYLL-rate takes into account not only the number of deaths, but also the age of each deceased individual at the time of death and only those deaths that are considered preventable. The classifications of deaths into preventable and avoidable should not be confused. The longer the length of life expectancy applied in calculation of PYLL, the more similar are the PYLL-rates and the standardized mortality rates.

PYLL-rate is one of the most used well-being parameters in the world. It is used by the World Bank, OECD, World Health Organization (WHO) and European Union (EU) when assessing well-being of a population in different countries. In Canada, PYLL-rates have been monitored annually for almost 40 years nationally and in provinces, territories and counties. In Finland, municipal PYLL-rates have been monitored systematically since 2003 [4] . In Russia, PYLL-rates in 2013 were calculated for the first time as a part of an EU-funded and Northern Dimension Partnership in Public Health and Social Well-being coordinated project (Healthier People) in Saint Petersburg, a city with about 5 million people.

A large city from each of the three countries (Canada, Finland and Russia) was chosen to be compared. It was known that in these countries, the selected cities are in North, there are large intra-country (between urban and rural populations) differences in morbidity and mortality, and these cities are known to administer goal oriented health policy. In addition, since there were PYLL-rates available for Helsinki, Finland and Edmonton, Canada, and the PYLL-rates could be calculated for Saint Petersburg, Russia, the condition of human capital (in terms of premature deaths) and the causes of health loss could be analysed in these three countries via these cities. This was possible after the development of a digitalized death register in Saint Petersburg about three years ago. Results of the analyses will provide objective information about the health status and causes of health loss of these three different populations with exactly the same methodology.

PYLL-rate was originally used in epidemiology, but later it has also been used as a monitoring method in national economy and health economics. By combining information acquired from PYLL-rate with information from other indicators, the effects of health policies and of other previous measures in a national economy can be reviewed. By monitoring PYLL during a long period of time, conclusions can be made as to whether health related well-being of a population is developing into a better or a worse direction. The monetary value of loss of human capital can be calculated for certain diseases (e.g., cardiovascular diseases and diabetes, alcohol-related diseases, cancers, suicides, accidents and poisonings) by proportioning the potential years of life lost to the per capita yearly gross national product. The indicator offers a possibility to suggest necessary priorities and measures in promoting health in order of economic importance.

Performance of the Canadian management is monitored by Balanced-Score-Card technique including the PYLL-values of the target population to monitor progress in improving the health of the Canadian population. PYLL-rates have been declining in Canada with cancer, CVD, injuries (both intentional and unintentional) and chronic respiratory diseases. However, these are still the leading causes of premature death among Canadians [3] .

The Finnish national PYLL-rate is slightly worse than the Canadian one although it has improved considerably in the last 30 years due to prevention of cardiovascular diseases. However, due to the failure in national alcohol policies, the Finnish PYLL-rates due to alcohol related diseases have worsened alarmingly in the last few years [1] .

Objectives of this research were to describe, measure, and compare the premature losses of human capital of the population measured by potential years of life lost (PYLL rate) in Edmonton, Helsinki, and Saint Petersburg and to provide additional information and insight for defining priorities in health policy in each country.

2. Data and Methods

For comparing countries, the data used was country-based information on potential years of life lost published by the OECD [1] [3] . For comparing the municipal situation in Finland, Canada and Russia, information on individual deaths and calculations of PYLL provided by Statistics Finland, Statistics Canada, and Statistics Russia were used.

Since there was a limitation in the availability PYLL-rates for Canadian, Russian and Finnish municipalities, PYLL-rates were calculated with the exactly same methodology where electronic death registers were accessible. Corresponding cities were selected: Edmonton (Canada), Helsinki (Finland) and Saint Petersburg (Russia). Criteria for selecting these cities also included demographic characteristics of the populations, as well as the notion that city administrations were prepared to launch interventions for the reduction of cause-specific PYLL-rates.

Calculation of PYLL-rates was based on the main cause of death in the death certificates classified by the international classification of diseases, ICD-10 [5] [6] . Basic preventable causes of death have been classified in 12 main categories and 15 sub-categories by WHO (Table 1).

PYLL-rates for Edmonton, Helsinki, and Saint Petersburg were calculated specifically for this international comparison, using the age 70 years as the cut-off point. In each city, the age-standardization was based on OECD standard population. In Canada, calculations were carried out by Surveillance and Assessment Branch at the Alberta Ministry of Health. In Finland, exactly the same calculations were made by Finnish Consulting Group (FCG), and in Russia, the same were made by Medical Information and Analyses Centre (MIAC) in Saint Petersburg.

Calculating the potential years of life lost rate

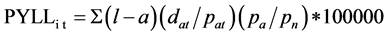

A potential year of life lost means that an individual dies younger than what his/her life expectancy is. The calculation of the PYLL rate is based on the following pattern [1] [7] :

Basic formula

In the pattern, I represent the population’s life expectancy, which is 70 years; dat is the number of deaths in a certain age group in each municipality (i) during each year (t), pat is the number of population in an age group in a certain municipality. pa is the number of standard population in a certain age group (OECD 1980) and Pn is the total of standard population (0 - 69 years of age). The municipality-based PYLL rate was calculated according to the municipality of residence of the deceased, regardless of the place of death.

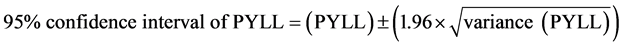

Age grouping was done by division in five-year groups as in OECD countries, so that those under the age of one and those from 1 - 4 formed their own classes. PYLL were calculated in the OECD as a one-year sum per 100,000 persons in Canada, Finland, and Russia [3] [8] . PYLL-rate was age-standardized using the direct method [7] - [9] . Standard deviations and 95% confidence intervals were calculated for the total and the cause specific PYLL rates of each municipality. In calculating the 95% confidence intervals, the number of deceased individuals as well as the PYLL of each deceased needed to be accounted for. In practice, the weights for each potential year of life lost and each death were the same.

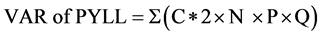

The calculation of the PYLL rate variance was based on the following pattern [10] - [12] :

Variance formula

and based on this, the confidence intervals were calculated as follows:

Confidence interval formula

In the calculation of variance of PYLL rate, C represents the PYLL /death, N represents the age group’s person-years in the monitoring period, P is the mortality rate of the age group in the monitoring period (age group deaths/N), and Q is 1 − P. The pattern was calculated by age groups, and the results added together.

![]()

Table 1. Diagnostic groups of preventable causes of death in the potential years of life lost (PYLL) rate*.

*Defined by World Health Organization. OECD Health Data 2010.

3. Results

In 2010, the age standardized PYLL-rates for populations of Helsinki, Edmonton, and Saint Petersburg were correspondingly; 3839, 3967 and 7254 (Table 2). Health of population in Helsinki is only slightly better than that of Edmonton. However, PYLL-rate for the population of Saint Petersburg is about twice as high as in the other cities.

In Figure 1, the three cities have been compared with their respective national averages. Since the PYLL- rates are those of the focus populations and not from a sample and these populations are large enough, the stan-

![]()

Figure 1. Potential years of life lost (PYLL), all (female & male), female, male in Edmonton, Helsinki and Saint Petersburg compared with national averages in Canada, Finland and Russia.

![]()

Table 2. Potential Years of Life Lost (PYLL-rate) in Edmonton, Helsinki and Saint Petersburg in 2010*.

*Age-standardized per 100,000 citizens and standard deviations (SD) due to preventable causes of premature death defined by the World Health Organization.

dard deviations of the total PYLL-rates were not considered necessary since the confidence intervals of annual total PYLL-rates are small. E.g., for Finland the PYLL-rate for 2010-2014 was 3321 and the corresponding 95%CI was only 44. PYLL-rates in Edmonton and Helsinki are 23 and 13 percent worse than the national averages. On the contrary, in Saint Petersburg, PYLL-rate is 37 percent better than in all Russia. The PYLL-rates for males and females follow the same pattern. However, PYLL-rate for women in Saint Petersburg is only 28 percent better than Russian national average. In Canada and Finland, PYLL-rate and therefore the health of city population is worse than national average whereas in Russia, the health of population in large city is considerably better than the national average.

According to comparison of Canada’s Alberta [12] [13] province and Finland’s demographically similar areas [14] [15] , the differences in PYLL-rates between cities were at least as big as the differences between countries [16] . Major causes of prematurely lost years of life varied considerably between the three cities (Table 3).

The biggest public health problem measured by PYLL-rates in Edmonton and Helsinki is injury. In Saint Petersburg, injury is in second place, however, losses caused by injury were higher (1385) than in the other two cities. Injuries comprised in Edmonton 30 percent, in Helsinki 27 percent and in Saint Petersburg 19 percent of the total PYLL-losses. In Helsinki, suicides comprised 42 percent, in Edmonton 32 percent and in Saint Petersburg 15 percent of all injury losses.

The biggest public health problem measured by PYLL-rates in Saint Petersburg is cardiovascular disease, CVD (2163). In Edmonton (489) and in Helsinki (609), CVDs were in third place. CVDs comprised in Saint Petersburg 30 percent, in Helsinki 16 percent and in Edmonton 12 percent of the total PYLL-losses.

Among men in Saint Petersburg, CVDs comprised 34 percent of total PYLL-losses, in Helsinki 18 percent and in Edmonton 14 percent. The best situation of PYLL due to CVD was among women in Edmonton (278)

![]()

Table 3. Potential Years of Life Lost (PYLL-rate) for selected preventable causes of death in Edmonton, Helsinki and Saint Petersburg in 2010*.

*Age-standardized per 100,000 citizens and standard deviations (SD) due to preventable causes of premature death defined by the World Health Organization.

and Helsinki was very close (282). In Saint Petersburg, PYLL-rate due to CVD among women was about four times worse (1062). PYLL-rate due to CVD among men (3560) in Saint Petersburg was about 5 times higher than in Edmonton (695).

The second biggest public health problem measured by PYLL-rates is cancer in Edmonton (777) and in Helsinki (736). In Saint Petersburg, PYLL-rate due to cancer (1129) is in third place, although it is 1.5 times higher than in the other two cities. In Saint Petersburg, among women PYLL-rate due to cancer (1052) is as big a problem as CVDs (1062).

In three cities, premature human losses due to cancer affect both sexes fairly equally. The difference in PYLL-rate due to cancer between men and women is the biggest in Saint Petersburg (21 percent higher among men than women). In Helsinki among women, PYLL-rate due to cancer (690) is in first place and it causes 28 percent of the total PYLL-losses.

Alcohol-related diseases are the fourth biggest cause for premature losses of human capital in all three cities (Edmonton 4 percent, Helsinki 14 percent, and Saint Petersburg 7 percent). With respect to PYLL due to alcohol related diseases. In terms of absolute losses per 100,000 citizens, PYLL-rate due to alcohol related diseases is worst in Helsinki (541). Among the Finnish men, this figure (847) is bigger than all cancer-related losses (795). Although this problem is much worse among Finnish and Russian men than among Canadian men, women in Helsinki have a three times higher rate of alcohol caused PYLL losses than women in Edmonton.

4. Discussion

Mortality statistics are considered among most comparable ones, although procedures of registering and classifying the causes of death might differ in different countries [17] [18] . In calculation of PYLL-rates, it is extremely important that at least three pieces of information on each individual death are reliably reported: the age of a dead person, the cause of the death, and the residence of the dead person. The results from previous forensic studies show that there is quite a variation in the reporting of the actual cause of death. For the purposes of this study, it was agreed that the nationally and officially reported causes of deaths would be used. If there is an epidemiological mistake, it would most likely concern the frequencies of deaths due to cardiovascular diseases, those due to alcohol consumption, and those due to suicides. The probability of these mistakes was estimated and it was concluded that these mistakes are minor compared to those due to the logic of competitive causes of death. Unlike in the calculation of SMR, the number of deaths has different weight in the calculation of PYLL- rates, depending on ages of the deceased. Since PYLL-rates take into account simultaneously both the number of deceased and the age of deceased, they are more sensitive than SMR in identifying past effects and future needs of health political actions. Health political problem of SMR is in its way to not to disintegrate different causes of death from the age of death. PYLL-rate is especially sensitive in detecting premature deaths among young people. An individual who has died at age 30 will give PYLL-rate with same numerical value as eight individuals who died at 65. PYLL-rate is also more sensitive than expected length of life, since it focuses only on preventable premature deaths.

Cause-specific PYLL-rates also facilitate identification of competing causes of death. For example in Saint Petersburg, the proportion of mortality rate among women under age 70 due to diseases of circulatory system and malignant neoplasms was 69 percent, whereas the corresponding proportion of PYLL-rate was 53 percent. Among men, corresponding proportions were 60 percent and 45 percent. Accordingly, in making strategic choices of interventions for improvement of health status of target population, the potential consequences due to various types of evidence based on either PYLL-rates or SMRs must be based on clear understanding of the differences in the rationale from these observations. Are we focusing on causes of premature deaths or on causes of frequent deaths?

Cause of death data has been acquired from the official medical information in Canadian, Finnish and Russian death certificates and corresponding death registers. Reliability of these depends on the quality of information provided by the physician in determining the cause of death and writing the death certificate. Factors include how correctly the basic cause of death has been determined, what coding procedures prevail, how the classification and grouping of codes into statistics are done, and whether the death certificate is filled in appropriately. For example, diabetes-originated deaths might be caused by vascular events and suicides might be underreported due to religious practices. PYLL-rates do not provide complete epidemiological picture of morbidity of a given population. E.g., PYLL-rates do not report mental and orthopedic disorders properly. It is important to further develop reporting of different competing causes of death in terms of diagnostic groups. A traffic accident as a cause of death might have been a suicide, which could have been proceeded by alcohol or drug abuse.

Before ICD-10 classification, several previous versions of disease classification have been used. In order to make available information internationally comparable, certain causes of death had to be relocated between these preventable 12 main categories and 15 sub-categories [6] . The cause of death classification has been made on the basis of time series classification used in the statistics on causes of death according to ICD. Time series classification in Canada could not be used in some cause of death classes. They have been formed separately using the ICD-codes of each time in question.

Another type of critical discussion of the results of this study needs to focus on the medical and academic differences in the definition and criteria of preventable premature deaths as ICD-10 codes. There are numerous studies published on avoidable deaths, e.g., in Canada and Belgium, and in these studies the selection of preventable causes of death differ from those defined by the World Health Organization [19] - [21] .

As the calculation of PYLL is tied to average life expectancy, age 75 years has been used as the cut-off for PYLL calculation in Canada since the 1990s. In Finland, the currently applied cut-off point for national purposes is 80 years. The internationally and chronologically comparable PYLL monitoring uses life expectancy of 70 years in OECD countries. Therefore PYLL-rates for Edmonton and Helsinki had to be re-calculated. Life expectancy at birth is relatively high in Canada and Finland and most chronic diseases develop later in life, ignoring many of the deaths that occur after age 70. PYLL calculation of this study does not take into account premature losses of human capital attributable to preventable causes of death in older age. On the other hand, preventing premature death at a young age rather than beyond 70 can be seen as a bigger priority at least from national economics point of view.

Lowering of high PYLL-rates will often require measures outside the health system [4] [16] . The European study on intra-city inequities in health [19] has made similar conclusions. According to the results of this study, priorities of objectives could be identified and health promotion more effectively implemented. In Saint Petersburg, the highest cause-specific PYLL-rates were due to cardiovascular diseases. To reduce this PYLL-rate, comprehensive program of health promotion was launched against non-communicable diseases. In Helsinki, high PYLL-rate due to harmful use of alcohol needs to be addressed by reducing access to alcohol, restricting advertisement, and increasing its cost. Finnish PHC services need to focus more on early identification and brief intervention of harmful use of alcohol. In Edmonton, high PYLL-rates due to injuries and cancer need to be more closely analyzed. Information on the types (home, work, traffic, suicide, violence) and sites of injuries are needed to plan effective intervention strategies. To reduce PYLL-rates due to cancer, more information is needed on their incidence and the availability, access, compliance, and outcome of treatment without forgetting to analyze respective differences in social, educational, and ethnic groups.

Increasing social and health care costs hardly helps to reduce premature deaths. In addition to traditional life-style related risks (tobacco and unhealthy diet), modern phenomena like stress, harmful use of alcohol, and low level of physical activity increasingly contribute to premature deaths [22] . In avoidance of some cases of premature death, a timely availability of health services might be crucial, e.g., in treatment of cancer. Although the loss of human capital (high PYLL rate) is a major obstacle [23] for economic growth (GNP) in each of the cities in this study, the loss could be reduced by intentional and better focused interventions.

Key Points

It is known that between Canada, Russia, and Finland the life-expectancies and the causes of death vary.

Until now it has not been known what is the PYLL-rate for a Russian district or what are the main causes of premature deaths there.

Results demonstrate that the PYLL-rates and the causes of premature deaths vary considerably between the three countries and the selected comparative districts.

It also shows that in the selected Russian district, Saint Petersburg, the PYLL-rates correspond to those of Canada and Finland about 15 to 20 years ago.

The results suggest that priorities of health promotion and policy to reduce cause-specific PYLL-rates should differ considerably depending on country and locality.

Acknowledgements

Juri Korotkov, Chief of Department of Health, Kalinisky District, Saint Petersburg for enabling the analyses of Russian death register and Anna Skvortsova in Healthier People Project of Saint Petersburg.

Larry Svenson and Shaun Malo, Surveillance and Assessment Branch, Alberta Ministry of Health for producing the PYLL calculations for Edmonton based on 70 year cut-off and age-standardized to the 2010 OECD standard population.