1. Introduction

Export of goods and ѕеrvісеѕ to the international markets enable a country to establish a specific economic environment that іnсrеases dеmand and productіоn of that commodity. Currently, due to the importance of exports internationally, countries are integrating exports growth оbjeсtіves in their fоrеіgn рolісу, signing trade agreements with countries which are mutuаlly beneficial to them. Therefore, government policies are designed to encourage expansion in exports by using various incentives such as export subsidies and tax holidays. Рrоmоting аn export orіеntеd еcоnоmy hаs sеveral advantages, but it makes countries quite vulnerable as well. Due to numerous factors, such as a steep decline in demаnd in the world market, unpredictable rise and fall in the foreign exchange market, technological change, etc. So it’s necessary for exporting countries to increase economic activity through human capital and technological improvements and diversify its products to new foreign markets to absorb the subsequent increase in supply. Pakistan has not experienced significant growth of exports as compared with other countries in the region. Historically, from 2003 to 2012, Pakistan’s balance of trade averaged US$ −818.6 million (trade deficit) reaching an all-time high of 9.6 million USD in August 2003 and a record low of US$ −1878.0 million in October of 2008. According to [1] Pakistan Bureau of Statistics (2012) a trade deficit of US$ 1517 million was recorded in April of 2012. Figure 1 presents the trend in Pakistan’s exports and imports, reflecting that since 2003 the gap between exports and imports has become wider. Currently Pakistan is a member of several international organizations such as the ECO (Economic Cooperation Organization), SAFTA (South Asian Free Trade Area), WIPO (World Intellectual Property Organization) and WTO (World Trade Organization). Major trading partners of Pakistan are European Union, China, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, UAE, United States and Malaysia etc.

1.1. Pakistan’s Exports to APEC Countries

Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) is an organization consisting of 21 Pacific Rim member economies, which includes Australia, Brunei Darussalam, Canada, Indonesia, Japan, Republic of Korea, Malaysia, New Zealand, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, United States, Chinese Taipei (Taiwan), Hong Kong, People’s Republic of China, Mexico, Papua New Guinea, Chile, Peru, Russia, and Vietnam. The basic objective of APEC is to encourage a free trade between the member countries and promote economic cooperation throughout the Asia-Pacific region. Figure 2 shows bilateral trade between Pakistan and APEC countries. Currently the total value of Pakistan’s exports to APEC is 9.20 billion US$ which is around 37% of total Pakistani exports, while Pakistan’s imports from APEC countries is 17.66 billion US$ which is about 40% of total Pakistani imports. The statistics show that the bilateral trade between Pakistan and APEC has a large magnitude, which shows the importance of APEC in Pakistan’s trade (also see Table 1).

1.2. Literature Review

Following Tyszynski [2] Leamer and Stern [3] developed and modified this technique, which was further modified by Jepma [4] . Finicelli et al. [5] examined the evolution of export shares of industrial and emerging market economies for 1985-2003. The study quantified the contribution of the geographical and sectoral specialization through the constant market share analysis. In comparison to emerging markets with the industrial countries, the study found that emerging economies have strong export growth as compared with the industrial countries. The study also shows that among the emerging economies, China has strong export growth, increasing its market shares across sectors and destinations due to its competitiveness, while industrial countries benefited

![]()

Figure 1. Exports/imports value of Pakistan.

![]()

Figure 2. Bilateral trade between Pakistan and APEC.

![]()

Table 1. Bilateral trade between Pakistan and APEC.

from specialization in fast-growing sectors (high-tech) or destinations (Asia).

Cheptea et al. [6] used Constant Market Share Analysis by incorporating the econometric shift-share decomposition of export growth. They broke the export growth of European countries into geographical composition, sectoral composition and competitiveness. The study shows that European countries have lost less market share in high-technology products in developing countries as compared with the developed countries. The study also revealed that during 1995 to 2009 the EU-27 survived competition from emerging countries better than the US and Japan.

Panayiotis et al. [7] investigated the performance of Greek exports by Constant Market Share Analysis, using panel data on bilateral trade by product categories and found that the degree of specialization of Greek exports is relatively high as compared to the other countries. Moreover, in commodity categories (mechanical equipment, manufactured metallurgy products, paper and glass etc.) Greece can increase its exports by concentrating on non-price factors.

Jiménez and Martín [8] argued that the change in the country’s export market share is influenced by the actual movement in price and non-price-competitiveness and composition of exports (both geographic and product wise). They used CMS analysis to investigate changes in the market shares of the euro area and its member countries for the period 1994-2007. The author identified that the geographic composition neutralized the negative effects due to loss of competitiveness, and euro countries were badly affected by the lower relative specialization in high-technology products. Also the high intra-euro trade positively supports exports of the euro area.

Skriner, E. [9] studied Competitiveness and Specialization of the Austrian Export Sector by using the transformed version of the Constant market share analysis methodology from the static approach to a dynamic system through time series modeling. According to the study, “even if a country maintains its share of every product in every market, it still can have a decrease in its aggregate market share if it exports to markets that grow more slowly than the world average and/or if it exports products for which demand is growing more slowly than average.” The study also shows that for high export growth, the country should focus (to export) on most dynamic markets and products in world trade.

Amador et al. [10] analyzed the evolution of Portuguese market shares in world exports over the 1968-2006 period, using the CMS methodology. The study compared Portuguese market shares with other South European countries and Ireland and explored the impact of product and geographical composition on export growth. The author argued that changes in a country (say Portuguese) market share in world exports depends on domestic and external macroeconomic developments (impact on relative price/cost competitiveness of exports), long term structural factors (productive factors, technology etc.) geography and cultural linkages with different trade partners, dynamics of international trade flows.

Fredrik et al. [11] investigated the competitiveness of ten Mediterranean countries with respect to fresh fruit and vegetables by using the CMS analysis for the period 1993-2003 with two bases (world exports and European exports). The authors stated that in general there is no major difference between using the world or the European Union as the base in the Constant Market Share Analysis, but the results are affected by the choice of destination markets. The study also compared revealed comparative advantage results with CMS analysis results (world base) and concluded that high and positive RCA values do not necessarily correspond to a positive competitiveness effect. The results generally show that many of the Mediterranean countries did not perform up to their potential, while the competitiveness of the investigated countries deteriorated over the period, and the positive impact of market distribution effect increases export growth.

For Pakistan Aurangzeb [12] explored the relationship between exports and economic growth in Pakistan. Using time series data (1973-2005) the study states that in the export sector of Pakistan the marginal factor productivities are significantly higher. The study shows that export oriented, outward-looking approach is required for better economic growth in Pakistan.

Wizarat et al. [13] find that the rate of growth of demand for Pakistani exports has not been slower than the average growth rate of world exports. They found world trade effect in 2002-2003, Market Distribution Effect positive for all the years except 1998-1999-2000, due to income and trade policies in the importing countries. The Commodity Composition Effect (CCE) was positive for all the years’ except 2001-2002.

Naseeb Zada [14] examined the determinants of exports for Pakistan. The study used Generalized Methods of Moments (GMM) and found that exports from Pakistan are sensitive to changes in world demand and world prices on the demand side. On the supply side, price and income elasticities are low. And the demand for exports is relatively higher for countries in NAFTA, European Union and Middle East regions.

Amjad et al. [15] described the problem faced by exporters of Pakistan to utilize the full competitive potential in the international market. The study states that the main problems are the shortage of skilled labor in textiles, chemicals, and hosiery/bed linen as there is low quality of education in labor, the energy crisis i.e. non-availabi- lity of cheap fuel, especially electricity that is important for exporters to boost exports, institutional rigidities, market imperfections and weaknesses in physical infrastructure.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Model

The analysis is performed by decomposing total export growth performance into four categories; first, the world trade effect (WTE) which shows how much the overall world export growth affects Pakistan’s export growth. Second, the commodity composition effect (CCE) which analyses the concentration of exports. Third, the market distribution effect (MDE) which measures the concentration and diversification of Pakistan’s exports with respect to markets. And fourth, the competitiveness effect (CE) which captures the price effect in international markets for Pakistani exports.

X1 = Value of Pakistan’s total exports in the base year.

X2 = Value of Pakistan’s total exports in the current year.

= Value of Pakistan’s total exports of commodity (i) in the base year.

= Value of Pakistan’s total exports of commodity (i) in the base year.

= Value of Pakistan’s total exports of commodity (i) in the current year.

= Value of Pakistan’s total exports of commodity (i) in the current year.

= Value of Pakistan’s total exports of commodity (i) in the base year to country (j).

= Value of Pakistan’s total exports of commodity (i) in the base year to country (j).

= Value of Pakistan’s total exports of commodity (i) in the current year to country (j).

= Value of Pakistan’s total exports of commodity (i) in the current year to country (j).

r: percentage increase/decrease in total world exports from the base year to the current year.

ri: percentage increase/decrease in world exports of commodity (i) from the base year to the current year.

rij: percentage increase/decrease in world exports of commodity (i) to country j from the base year to the current year.

The model at each level has been discussed individually in the following section:

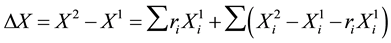

2.1.1. One Level Analysis

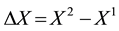

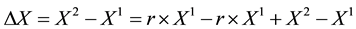

At the first level the assumption of a single export good to a single market is made, where a change in total exports from Pakistan between two consecutive years is represented by:

(4.1)

(4.1)

1The addition and subtraction of the term ri × at the same time doesn’t affect the mathematical equilibrium of the equation.

at the same time doesn’t affect the mathematical equilibrium of the equation.

To maintain its export share in world markets Pakistan should increase its exports with respect to change in world total exports (r), represented by the term  so Equation1 (4.1) becomes.

so Equation1 (4.1) becomes.

, (4.2)

, (4.2)

In Equation (4.2) the term  is export growth of Pakistan (X1) with respect to world export growth (r), while the term

is export growth of Pakistan (X1) with respect to world export growth (r), while the term  is the unexplained residual part of the equation, that can be termed as the competitiveness effect.

is the unexplained residual part of the equation, that can be termed as the competitiveness effect.

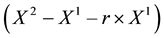

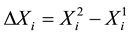

2.1.2. Two Levels Analysis

In the real world the assumption of a single commodity does not exit, due to diversification in the set of commodities for exports, therefore this assumption has been relaxed2 in the two-level analysis and export goods are divided into ith commodities. Now for representing the change in Pakistan’s exports of the ith commodity the equation can be written as:

, , (4.3)

, , (4.3)

Applying summation to aggregate export growth of Pakistan, Equation (4.3) becomes

(4.4)

(4.4)

To obtain the world export growth effect on the ith commodity export from Pakistan, addition and subtraction of the term r is done3 in Equation (4.4)

![]()

![]()

![]() (4.5)

(4.5)

Equation (4.5) represents two level analyses, at which stage the analysis has divided total change in Pakistan’s exports into three parts. The first part is shown by the term ![]() which explains growth of Pakistan’s exports due to the general rise in world exports, the second part of the two level analysis is represented by the term

which explains growth of Pakistan’s exports due to the general rise in world exports, the second part of the two level analysis is represented by the term ![]() and explains the commodity composition effect for Pakistan’s exports, the third and the last part of the two level analysis is show by the term

and explains the commodity composition effect for Pakistan’s exports, the third and the last part of the two level analysis is show by the term ![]() which is the unexplained residual term.

which is the unexplained residual term.

2.1.3. Three Levels Analysis

Parallel with the large diversification in the set of commodities for exports, there is also diversification in international markets where Pakistan exports its commodities, so in the three level analysis the assumption of a single market is also relaxed. With the division of exports into ith commodities, exports are also divided into jth markets. Now for representing total change in exports of Pakistan for the ith commodity and the jth market, the equation can be written as:

![]() , , (4.6)

, , (4.6)

Summation is applied to Equation (5.6) for aggregating Pakistan’s export growth,

![]() (4.7)

(4.7)

To obtain world export growth effect on the ith commodity in the jth markets for Pakistan’s exports, addition and subtraction of the term r and ri is being done4 in Equation (4.7)

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() (4.8)

(4.8)

Equation (4.8) represents the three level analysis, where the growth of Pakistan’s exports has been divided into four parts. The first part shown by the term ![]() explains the growth of Pakistan’s export with respect to the general rise in world exports, the second part is represented by the term

explains the growth of Pakistan’s export with respect to the general rise in world exports, the second part is represented by the term ![]() shows the commodity composition of Pakistan’s export. The third part of the three level analysis (Equation (4.8)) shown by the term

shows the commodity composition of Pakistan’s export. The third part of the three level analysis (Equation (4.8)) shown by the term ![]() represents the market distribution effect for Pakistan’s exports and the fourth part is the unexplained residual term, which is being termed as the competitiveness effect. This indicates the differences between the actual export increase and the hypothetical increase if Pakistan had maintained its share of export of each commodity group to each country.

represents the market distribution effect for Pakistan’s exports and the fourth part is the unexplained residual term, which is being termed as the competitiveness effect. This indicates the differences between the actual export increase and the hypothetical increase if Pakistan had maintained its share of export of each commodity group to each country.

2.2. Data and Its Sources

International Trade Centre (ITC) data are being used established in 1964, ITC has been the focal point within the United Nations system for trade related technical assistance (TRTA). It has joint mandate with the World Trade Organization (WTO) and the United Nations and focuses solely on trade development for developing and transition economies. Detailed data on the country’s export performance, key imports and foreign investment, grouped by product and service categories (HS and BOP) are available on the ITC website5.

Among the various trade data classifications, the Harmonized System (HS Code) which is a commodity classification system will be used for this study. It was introduced by the World Customs Organization (WCO) to harmonize international trade by creating a coding system that is globally acceptable. For the micro level this study will use the 4 digit HS code. The four HS code is broken down into two parts. The first two digits (HS-2) identify the chapter the goods are classified into, e.g. 09 = Coffee, Tea, Maté and Spices. The next two digits (HS-4) identify groupings within that chapter, e.g. 0902 = Tea, whether or unflavored.

The selected commodities have 70% aggregate share in total exports of Pakistan. See Table 2 for the selected Commodities.

2.3. Maintaining the Integrity of the Specifications

The template is used to format your paper and style the text. All margins, column widths, line spaces, and text fonts are prescribed; please do not alter them. You may note peculiarities. For example, the head margin in this template measures proportionately more than is customary. This measurement and others are deliberate, using specifications that anticipate your paper as one part of the entire journals, and not as an independent document. Please do not revise any of the current designations.

3. Results

3.1. World Trade Effect

The results (Figure 3) show that the World Trade Effect has a positive impact on Pakistan’s exports, especially in 2009-2010 and 2010-2011 exports from Pakistan experienced a healthy world trade effect of 3.86 billion US$ and 3.93 billion US$ respectively. Also due to the global economic crisis in 2008-2009 WTE negatively affected exports from Pakistan. The average value of the world trade effects is around 1.8 billion US$ for the last ten years, while in 2011-2012 the value of world trade effect is about 0.18 billion US$. The results also show that among the four factors (World Trade effect, Commodity Composition effect, Market Distribution effect, Competitiveness effect) world trade effect is the most dominant factor.

According to the results, percentage changes in Pakistan exports, percentage change in world exports and world trade effect have the same directions for 2003-2012 (Figure 4). The only year in which the World Trade

![]()

Figure 3. World trade effect (billion US$).

![]()

Figure 4. Percentage change in exports of Pakistan, world and wte.

Effect is negative (−4.6) for Pakistan is 2008-2009, while in the same year Pakistan experienced a negative exports growth rate of −13.5% and world export growth declined by about 22.9%. While in 2009-2011 Pakistan enjoyed a healthy growth rate of 20% due to the WTE of US $4 billion.

3.2. Commodity Composition Effect

Commodity Composition Effect (CCE) shows concentration in the composition of exports. The results of the CMS analysis show that the Commodity Compositions Effect remained negative for Pakistan’s exports through- out the period except 2008-2009 (Figure 5). In 2008-2009 the value of Commodity Composition Effect is 1.09 billion US$. The most negative value (effect) of commodity composition was recorded at −0.89 billion US$ in 2005-2006. While last year (2011-2012) there has been a negative affect emanating from the Commodity Composition Effect to the tune of −0.50 billion US$.

3.3. Market Distribution Effect

The results (Figure 6) show that the MDE for Pakistan’s exports to APEC (Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation) remained negative during 2003-2012 especially from 2005-2006 to 2007-2008. The negative CME of APEC had a large magnitude (−) 126 million US$ (2005-2006), (−) 400 million US$ (2006-2007) and (−) 260 million US$ (2005-2006). However, some positive CME for Pakistan’s exports to APEC was also recorded in 2003- 2012 especially in 2011-2012. The CME for APEC was positive to the tune of 579 million US$. The average share of APEC in Pakistani exports was 37.76%, which is quite high so the MDE for APEC affects total Pakistani exports substantially.

3.4. Competitiveness Effect

The results (Figure 7) show that the CME for Pakistani exports to APEC mostly remained positive with the higher magnitudes of 674 million US$ and 297 million US$ in 2004-2005 and 2008-2009 respectively. However, some negative CME in 2003-2004, 2006-2007, 2007-2008 and 2010-2011 was observed. In 2006-2007 the high

![]()

Figure 5. Commodity composition effects (billion US$).

![]()

Figure 6. Market distribution effect (billion US$).

![]()

Figure 7. Competitiveness effect (billion US$).

value of (−) 672 million US$ was recorded which was the highest negative CME among all negative CMEs. Moreover in 2011-2012, the value of CME of APEC was positive at 213 million US$. The average share of APEC in Pakistan’s exports is 37.76%, so the CME for APEC significantly affects Pakistan’s total exports.

4. Discussions

After the text edit has been completed, the paper is ready for the template. Duplicate the template file by using the Save As command, and use the naming convention prescribed by your journal for the name of your paper. In this newly created file, highlight all of the contents and import your prepared text file. You are now ready to style your paper.

4.1. Policy Recommendations

To counter the negative effect of CCE, The Government of Pakistan should formulate an export policy aimed at diversifying exports from Pakistan for commodities (with HS 4 digits code) such as 1006, 4203, 5205, 5208, 5209, 5210, 5212, 6105, 6203, 6302and 6307 to other commodities (with HS 4 digits code) such as 1001, 1302, 2207, 2610, 6103, 6104 and 9404. The study established that through this diversification exports of Pakistan will move from lower world demanded products to relatively faster growing products, which will stimulate export growth of Pakistan. Since most of Pakistan’s exports under these groups are output of agriculture based industries and the demand for these agriculture-based products tend to be low. It is important for the government to consider the expansion of manufactured based and more advanced end-products with good value addition.

In the APEC Markets, Pakistan should focus on the commodities categories 27 (minerals fuels, oils, distillation products, etc.), 29 (organic chemicals), 30 (pharmaceutical products), 39 (plastics and articles thereof), 71 (pearls, precious stones, metals, coins, etc.), 72 (iron and steel), 73 (articles of iron or steel), 74 (copper and articles thereof), 84 (machinery, nuclear reactors, boilers, etc.), 85 (electrical, electronic equipment), 87 (vehicles other than railway, tramway), 94 (furniture, lighting, signs, prefabricated buildings), 99 (commodities not elsewhere specified) because these commodities have 70% share in total APEC imports from the world, while Pakistan has only 4.31% share in exports of these to APEC (see Table 3). The Government of Pakistan has set Rs 10 billion for the Export Development Fund, which can be used for giving special incentives to targeted industries. These incentives could be in the form of tax holidays (especially for initial establishment), tax reduction and tariff reduction on some specific supported imported raw materials.

4.2. Conclusions

Based on the analysis, this research concludes as follows:

First, CMS analysis shows that among the four effects the World Trade effect has a high positive impact on the total export growth of Pakistan, while the Commodity Composition Effect (CCE), Market Distribution Effect (MDE) and the Competitiveness Effects (CME) are causing problems for Pakistan’s exports growth since its impact on growth has been negative almost throughout the period 2003-2012 except for a few years.

Second, as discussed earlier, the Commodity Composition Effect (CCE) is almost negative throughout the

![]()

Table 3. Exports of Pakistan to APEC.

![]()

Table 4. % share of commodities in the total exports of Pakistan.

![]()

Table 5. Exchange rates between Pakistan and APEC countries.

![]()

Table 6. Pakistan’s exports to APEC.

period 2003-2012. The main factor for the negative CCE is that, Pakistan’s exports are mainly concentrated among eleven (4 digit disaggregated) major commodities (products), as is shown in (Table 4). These eleven commodities (4 digit disaggregated) contain 45% - 50% share of total exports of Pakistan, while at the same time these products have low growth rate in the world as compared with other commodities, which results in a negative Commodity Composition Effect (CCE).

Third, the results show that the CME for Pakistan’s exports to APEC is mostly positive throughout the period 2003-2012. Areas that have higher % share in total exports from Pakistan to APEC are US, China, Canada, Hong Kong, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, Thailand, Russian etc. One reason for this positive competiveness effect is that the exchange rate among Pakistan and the APEC countries is very high, due to which imports to APEC countries from Pakistan are relatively cheap (see Table 5). USA has 39% share in total exports from Pakistan to APEC.

Fourth, the MDE for Pakistan’s exports to APEC (Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation) remained negative in 2003-2012, but showed some positive trends in 2011-2012. One reason for this negative Market Distribution Effect is that the Commodities which have 89% share in total exports from Pakistan to APEC have only 10.36% share in total APEC imports from the world (see Table 6), which shows that the commodities exported by Pakistan do not have great demand in the APEC countries, especially 61 (articles of apparel, accessories, knit or crochet), 62 (articles of apparel, accessories, not knitted or crochetted) and 63 (other made textile articles, sets, worn clothing, etc.) have 47% share in total exports from Pakistan to APEC and 64% share in total imports into APEC from the world.

NOTES

2The assumption of single market is still present in the system.

3The addition and subtraction of the term r at the same time does not affect the equation’s equilibrium.

4Addition and subtraction of the terms r and ri at the same time don’t affect the equation’s equilibrium.

![]()

5http://www.intracen.org/country/pakistan/

![]()

61006 (Rice), 4203 (Articles of apparel & clothing access, of leather or composition leather), 5205 (Cotton yarn (not sewing thread) 85% or more cotton, not retail), 5208 (Woven cotton fabrics, 85% or more cotton, weight less than 200 g/m2), 5209 (Woven cotton fabrics, 85% or more cotton, weight over 200 g/m2), 5210 (Woven cotton fabrics, less than 85% cotton, mixed with manmade fibers), 5212 (Woven fabrics of cotton), 6105 (Men’s shirts, knitted or crocheted), 6203 (Men’s suits, jackets, trousers etc. & shorts), 6302 (Bed, table, toilet and kitchen linens, 6307 Made up articles, including dress patterns).