1. Introduction

Let  be a given real symmetric

be a given real symmetric  matrix. In this paper we consider the problem of finding a low-rank symmetric positive semidefinite matrix which is nearest to

matrix. In this paper we consider the problem of finding a low-rank symmetric positive semidefinite matrix which is nearest to  with regard to a certain matrix norm. Let

with regard to a certain matrix norm. Let  be a given unitarily invariant matrix norm on

be a given unitarily invariant matrix norm on . (The basic features of such norms are explained in the next section.) Let

. (The basic features of such norms are explained in the next section.) Let  be a given positive integer such that

be a given positive integer such that , and define

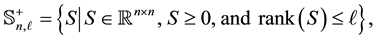

, and define

where the notation  means that

means that  is symmetric and positive semidefinite. Then the problem to solve has the form

is symmetric and positive semidefinite. Then the problem to solve has the form

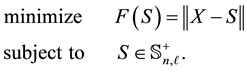

(1.1)

(1.1)

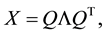

The need for solving such problems arises in certain matrix completion methods that consider Euclidean distance matrices, see [1] or [2] . Since  is assumed to be a symmetric matrix, it has a spectral decom- position

is assumed to be a symmetric matrix, it has a spectral decom- position

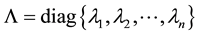

(1.2)

(1.2)

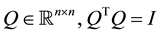

where , is an orthonormal matrix

, is an orthonormal matrix

is a diagonal matrix, and

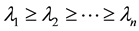

are the eigenvalues of ![]() in decreasing order. If

in decreasing order. If![]() , then

, then ![]() and the spectral decomposition (1.2) coincides with the SVD of

and the spectral decomposition (1.2) coincides with the SVD of![]() . In this case the solution of (1.1) is given by the Eckart-Young-Mirsky theorem. See the next section.

. In this case the solution of (1.1) is given by the Eckart-Young-Mirsky theorem. See the next section.

The rest of the paper assumes, therefore, that![]() . In this case the solution of (1.1) is related to that of the problem

. In this case the solution of (1.1) is related to that of the problem

![]() (1.3)

(1.3)

where

![]()

Let ![]() be a non-negative integer that counts the number of positive eigenvalues. That is

be a non-negative integer that counts the number of positive eigenvalues. That is

![]() (1.4)

(1.4)

Let the diagonal matrix ![]() denotes the positive part of

denotes the positive part of![]() ,

,

![]() (1.5)

(1.5)

(If ![]() then

then![]() , and

, and ![]() is the null matrix.) Then, as we shall see in Section 3, the matrix

is the null matrix.) Then, as we shall see in Section 3, the matrix

![]()

solves (1.3) in any unitarily invariant norm.

If ![]() then, clearly,

then, clearly, ![]() is also a solution of (1.1). Hence in the rest of the paper we assume that

is also a solution of (1.1). Hence in the rest of the paper we assume that![]() . This assumption implies that the diagonal matrix

. This assumption implies that the diagonal matrix

![]() (1.6)

(1.6)

belongs to![]() . The aim of the paper is to show that the matrix

. The aim of the paper is to show that the matrix

![]()

solves (1.1) for any unitarily invariant norm.

Let ![]() be a given real

be a given real ![]() matrix. Then another related problem is

matrix. Then another related problem is

![]() (1.7)

(1.7)

The relation between (1.7) and (1.3) is seen when using the Frobenius matrix norm. Let ![]() be a symmetric matrix and let

be a symmetric matrix and let ![]() be a skew-symmetric matrix. Then, clearly,

be a skew-symmetric matrix. Then, clearly,

![]() (1.8)

(1.8)

Recall also that any matrix ![]() has a unique presentation as the sum

has a unique presentation as the sum ![]() where

where ![]() is symmetric and

is symmetric and ![]() is skew-symmetric. Consequently, for any symmetric matrix,

is skew-symmetric. Consequently, for any symmetric matrix, ![]() say,

say,

![]() (1.9)

(1.9)

Therefore, when using the Frobenius norm, a solution of (1.3) provides a solution of (1.7). This observation is due to Higham [3] . A matrix that solves (1.7) or (1.3) is called “positive approximant”. Similarly, the term “low-rank positive approximant” refers to a matrix that solves (1.1).

The current interest in positive approximants was initiated in Halmos’ paper [4] , which considers the solution of (1.7) in the spectral norm. Rogers and Ward [5] considered the solution of (1.7) in the Schatten-p norm, Ando [6] considered this problem in the trace norm, and Higham [3] considered the Frobenius norm. Halmos [4] has considered the positive approximant problem in a more general context of linear operators on a Hilbert space. Other positive approximants problems (in the operators context) are considered in [7] - [11] . The problems (1.1), (1.3) and (1.7) fall into the category of “matrix nearness problems”. Further examples of matrix (or operator) nearness problems are discussed in [12] - [18] . A review of this topic is given in Higham [19] .

The plan of the paper is as follows. In the next section we introduce notations and tools which are needed for the coming discussions. In Section 3 we show that ![]() solves (1.3). Section 4 considers the solution of (1.1) in Frobenius norm. This involves the Eckart-Young theorem. In the next sections Mirsky theorem extends the results to Schatten-p norms, the trace norm, and the spectral norm. Then it is proved that

solves (1.3). Section 4 considers the solution of (1.1) in Frobenius norm. This involves the Eckart-Young theorem. In the next sections Mirsky theorem extends the results to Schatten-p norms, the trace norm, and the spectral norm. Then it is proved that ![]() solves (1.1) in any unitarily invariant norm. The proof of this claim requires a subtle combination of Ky Fan dominance theorem, a modified pinching principle, and Mirsky theorem.

solves (1.1) in any unitarily invariant norm. The proof of this claim requires a subtle combination of Ky Fan dominance theorem, a modified pinching principle, and Mirsky theorem.

2. Notations and Tools

In this section we introduce notations and facts which are needed for coming discussions. Here ![]() denotes a real

denotes a real ![]() matrix with

matrix with![]() . Let

. Let

![]() (2.1)

(2.1)

be an SVD of![]() , where

, where ![]() is an

is an ![]() orthogonal matrix,

orthogonal matrix, ![]() is an

is an ![]() orthogonal matrix, and

orthogonal matrix, and ![]() is an

is an ![]() diagonal matrix. The singular values of

diagonal matrix. The singular values of ![]() are assumed to be nonnegative and sorted to satisfy

are assumed to be nonnegative and sorted to satisfy

![]() (2.2)

(2.2)

The columns of ![]() and

and ![]() are called left singular vectors and right singular vectors, respectively. These vectors are related by the equalities

are called left singular vectors and right singular vectors, respectively. These vectors are related by the equalities

![]() (2.3)

(2.3)

A further consequence of (2.1) is the equality

![]() (2.4)

(2.4)

Moreover, let ![]() denotes the rank of

denotes the rank of![]() . Then, clearly,

. Then, clearly,

![]() (2.5)

(2.5)

So (2.4) can be rewritten as

![]() (2.6)

(2.6)

Let the matrices

![]() (2.7)

(2.7)

be constructed from the first ![]() columns of

columns of ![]() and

and![]() , respectively. Let

, respectively. Let ![]() be a

be a ![]() diagonal matrix. Then the matrix

diagonal matrix. Then the matrix

![]() (2.8)

(2.8)

is called a rank-k truncated SVD of![]() . (If

. (If ![]() then this matrix is not unique.)

then this matrix is not unique.)

Let ![]() denote the

denote the ![]() entries of the matrices

entries of the matrices![]() , respectively. Then (2.4) indicates that

, respectively. Then (2.4) indicates that

![]() (2.9)

(2.9)

and

![]() (2.10)

(2.10)

where the last inequality follows from the Cauchy-Schwarz inequality and the fact that the columns of ![]() and

and ![]() have unit length.

have unit length.

Another useful property regards the concepts of majorization and unitarily invariant norms. Recall that a matrix norm ![]() on

on ![]() is called unitarily invariant if the equalities

is called unitarily invariant if the equalities

![]() (2.11)

(2.11)

are satisfied for any matrix![]() , and any pair of unitary matrices

, and any pair of unitary matrices ![]() and

and![]() . Let

. Let ![]() and

and ![]() be a given pair of

be a given pair of ![]() matrices with singular values

matrices with singular values

![]()

respectively. Let ![]() and

and ![]() denote the corresponding n-vectors of singular values. Then the weak majorization relation

denote the corresponding n-vectors of singular values. Then the weak majorization relation ![]() means that these vectors satisfy the inequality

means that these vectors satisfy the inequality

![]() (2.12)

(2.12)

In this case we say that ![]() is weakly majorized by

is weakly majorized by![]() , or that the singular values of

, or that the singular values of ![]() are weakly majorized by those of

are weakly majorized by those of![]() . The dominance theorem of Fan [20] [21] relates these two concepts. It says that if the singular values of

. The dominance theorem of Fan [20] [21] relates these two concepts. It says that if the singular values of ![]() are weakly majorized by those of

are weakly majorized by those of ![]() then the inequality

then the inequality

![]() (2.13)

(2.13)

holds for any unitarily invariant norm. For detailed proof of this fact see, for example, [8] , [20] - [23] . The most popular example of an unitarily invariant norm is, perhaps, the Frobenius matrix norm

![]() (2.14)

(2.14)

which satisfies

![]() (2.15)

(2.15)

Other examples are the Schatten p-norms,

![]() (2.16)

(2.16)

and Ky Fan k-norms,

![]() (2.17)

(2.17)

The trace norm,

![]() (2.18)

(2.18)

is obtained for ![]() and

and![]() , while the spectral norm

, while the spectral norm

![]() (2.19)

(2.19)

corresponds to ![]() and

and![]() . The use of Ky Fan k-norms enables us to state the dominance principle in the following way.

. The use of Ky Fan k-norms enables us to state the dominance principle in the following way.

Theorem 1 (Ky Fan dominance theorem) The Inequality (2.13) holds for any unitarily invariant norm if and only if

![]() (2.20)

(2.20)

Another useful tool is the following “rectangular” version of Cauchy interlacing theorem. For a proof of this result see ( [24] , p. 229) or ( [25] , p. 1250).

Theorem 2 (A rectangular Cauchy interlace theorem) Let the ![]() matrix

matrix ![]() have the singular values (2.2). Let the

have the singular values (2.2). Let the ![]() matrix

matrix ![]() be a submatrix of

be a submatrix of ![]() which is obtained by deleting

which is obtained by deleting ![]() rows and

rows and ![]() columns of

columns of![]() . That is,

. That is, ![]() and

and![]() . Define

. Define ![]() and let

and let

![]()

denote the singular values of![]() . Then

. Then

![]() (2.21)

(2.21)

To ease the coming discussions we return to square matrices. In the next assertions ![]() is an arbitrary real

is an arbitrary real ![]() matrix. Combining the interlace theorem with the dominance theorem leads to the following corollary.

matrix. Combining the interlace theorem with the dominance theorem leads to the following corollary.

Theorem 3 Let the ![]() matrix

matrix ![]() be obtained from

be obtained from ![]() by setting to zero all the entries in the last

by setting to zero all the entries in the last ![]() rows and columns of

rows and columns of![]() . Then the inequality

. Then the inequality

![]() (2.22)

(2.22)

holds for any unitarily invariant norm.

Theorem 4 Let the ![]() diagonal matrix

diagonal matrix

![]()

be obtained from the diagonal entries of![]() . Then

. Then

![]() (2.23)

(2.23)

in any unitarily invariant norm.

Proof. There is no loss of generality in assuming that the diagonal entries of ![]() are ordered such that

are ordered such that

![]()

Let the matrix ![]() be defined as in Theorem 3. Then from (2.10) and (2.22) we conclude that

be defined as in Theorem 3. Then from (2.10) and (2.22) we conclude that

![]()

which proves (2.23). ![]()

Corollary 5 The diagonal matrix

![]()

satisfies

![]() (2.24)

(2.24)

in any unitarily invariant norm.

Lemma 6 Let ![]() and

and ![]() be a pair of real symmetric

be a pair of real symmetric ![]() matrices that satisfy

matrices that satisfy

![]()

Then

![]()

in any unitarily invariant norm.

Proof. Using the spectral decomposition of ![]() it is possible to assume that

it is possible to assume that ![]() is a diagonal matrix:

is a diagonal matrix:

![]()

The matrix ![]() is positive semidefinite and, therefore, has non-negative diagonal entries. This observation implies the inequalities

is positive semidefinite and, therefore, has non-negative diagonal entries. This observation implies the inequalities

![]()

and

![]()

while (2.23) gives

![]()

Theorem 7 (The pinching principle) Let the matrix ![]() be partitioned in the form

be partitioned in the form

![]() (2.25)

(2.25)

where ![]() and

and![]() . Let the

. Let the ![]() matrix

matrix

![]() (2.26)

(2.26)

denote the “pinched” version of![]() . Then the inequality

. Then the inequality

![]() (2.27)

(2.27)

holds in any unitarily invariant norm.

Proof. Using the SVD of ![]() we obtain an pair of

we obtain an pair of ![]() orthonormal matrices,

orthonormal matrices, ![]() and

and![]() , such that

, such that

![]() is a diagonal matrix that contains the singular values of

is a diagonal matrix that contains the singular values of![]() . Similarly there exists a pair of

. Similarly there exists a pair of ![]() orthonormal matrices,

orthonormal matrices, ![]() and

and![]() , such that

, such that ![]() is a diagonal matrix that contains

is a diagonal matrix that contains

the singular values of![]() . The related

. The related ![]() matrices

matrices

![]()

are orthonormal matrices, and

![]() (2.28)

(2.28)

is a diagonal matrix. Moreover, comparing ![]() with

with ![]() shows that

shows that

![]() (2.29)

(2.29)

Hence a further use of (2.23) gives

![]()

Equality (2.28) relates the singular values of ![]() with those of the matrices

with those of the matrices ![]() and

and![]() : Each singular value of

: Each singular value of ![]() is a singular value of

is a singular value of![]() . Similarly, each singular value of

. Similarly, each singular value of ![]() is a singular value of

is a singular value of![]() . Conversely, each singular value of

. Conversely, each singular value of ![]() is a singular value of

is a singular value of ![]() or a singular value of

or a singular value of![]() . The last observation enables us to sharpen the results in certain cases. This is illustrated in Lemmas 8-11 below, which seem to be new. We will use these lemmas in the proofs of Theorems 18-21.

. The last observation enables us to sharpen the results in certain cases. This is illustrated in Lemmas 8-11 below, which seem to be new. We will use these lemmas in the proofs of Theorems 18-21.

Lemma 8 (Pinching in Schatten p-norms)

![]() (2.30)

(2.30)

Lemma 9 (Pinching in the trace norm)

![]() (2.31)

(2.31)

Lemma 10 (Pinching in the spectral norm)

![]() (2.32)

(2.32)

Lemma 11 (Pinching in Ky Fan k-norms) Let ![]() and

and ![]() be a pair of positive integers that satisfy

be a pair of positive integers that satisfy

![]()

Then

![]() (2.33)

(2.33)

Proof. The sum ![]() is formed from

is formed from ![]() singular values of

singular values of![]() , while the sum defined by

, while the sum defined by ![]() is composed from the

is composed from the ![]() largest singular values of

largest singular values of![]() .

. ![]()

The next tools consider the problem of approximating one matrix by another matrix of lower rank. Let ![]() by a given matrix with SVD that satisfies (2.1)-(2.8). Let

by a given matrix with SVD that satisfies (2.1)-(2.8). Let ![]() be a given integer, and let

be a given integer, and let

![]()

denote the related set of low-rank matrices. Then here we seek a matrix ![]() that is nearest to

that is nearest to ![]() in a certain matrix norm. The difficulty stems from the fact that

in a certain matrix norm. The difficulty stems from the fact that ![]() is not a convex set. Let

is not a convex set. Let ![]() denote a rank-k truncated SVD of

denote a rank-k truncated SVD of ![]() as defined in (2.8). Then the Eckart-Young theorem [26] says that

as defined in (2.8). Then the Eckart-Young theorem [26] says that ![]() solves this problem in the Frobenius norm. The extension of this result to any unitarily invariant norm is due to Mirsky [27] . (Recall that

solves this problem in the Frobenius norm. The extension of this result to any unitarily invariant norm is due to Mirsky [27] . (Recall that ![]() is not always unique. In such cases the nearest matrix is not unique.) A detailed statement of these assertions is given below. For recent discussions and proofs see [25] .

is not always unique. In such cases the nearest matrix is not unique.) A detailed statement of these assertions is given below. For recent discussions and proofs see [25] .

Theorem 12 (Eckart-Young) The inequality

![]()

holds for any matrix![]() . Moreover, the matrix

. Moreover, the matrix ![]() solves the problem

solves the problem

![]()

giving the optimal value of

![]()

Theorem 13 (Mirsky) Let ![]() be any unitarily invariant norm on

be any unitarily invariant norm on![]() . Then the inequality

. Then the inequality

![]()

holds for any matrix![]() . In other words, the matrix

. In other words, the matrix ![]() solves the problem

solves the problem

![]()

3. Positive Approximants of Symmetric Matrices

In this section we consider the solution of problem (1.3). Since ![]() is a unitarily invariant norm, the spectral decomposition (1.2) enables us to convert (1.3) into the simpler form

is a unitarily invariant norm, the spectral decomposition (1.2) enables us to convert (1.3) into the simpler form

![]() (3.1)

(3.1)

whose solution provides a solution of (1.3).

Theorem 14 Let the matrix ![]() be defined as in (1.5). Then

be defined as in (1.5). Then ![]() solves (3.1) in any unitarily invariant norm.

solves (3.1) in any unitarily invariant norm.

Proof. Let the diagonal matrix ![]() be defined by the equality

be defined by the equality

![]()

That is

![]() (3.2)

(3.2)

Let ![]() be some matrix in

be some matrix in ![]() and let the matrix

and let the matrix ![]() be defined by the equality

be defined by the equality

![]() (3.3)

(3.3)

Then the proof is concluded by showing that

![]() (3.4)

(3.4)

Let the diagonal matrix

![]() (3.5)

(3.5)

be obtained from the last ![]() diagonal entries of

diagonal entries of![]() . Then Corollary 5 implies that

. Then Corollary 5 implies that

![]() (3.6)

(3.6)

On the other hand, since![]() , the diagonal entries of

, the diagonal entries of ![]() are non-negative, which implies the inequalities

are non-negative, which implies the inequalities

![]() (3.7)

(3.7)

and

![]() (3.8)

(3.8)

Now combining (3.6) and (3.8) gives (3.4) ![]()

Theorem 14 is not new, e.g. ( [8] , p. 277) and [9] . However, the current proof is simple and short. In the next sections we extend these arguments to derive low-rank approximants.

4. Low-Rank Positive Approximants in the Frobenius Norm

In this section we consider the solution of problem (1.1) in the Frobenius norm. As before, the spectral decom- position (1.2) can be used to “diagonalize” the problem and the actual problem to solve has the form

![]() (4.1)

(4.1)

Theorem 15 Let the matrix ![]() be defined as in (1.6). Then this matrix solves (4.1)

be defined as in (1.6). Then this matrix solves (4.1)

Proof. Let the diagonal matrix ![]() be defined by the equality

be defined by the equality

![]()

That is,

![]() (4.2)

(4.2)

and

![]() (4.3)

(4.3)

Let ![]() be some matrix in

be some matrix in ![]() and let the matrix

and let the matrix ![]() be defined by the equality

be defined by the equality

![]() (4.4)

(4.4)

Then the proof is concluded by showing that

![]() (4.5)

(4.5)

This aim is achieved by considering a partition of ![]() and

and ![]() in the form

in the form

![]() (4.6)

(4.6)

where ![]() and

and ![]() are

are ![]() matrices, while

matrices, while ![]() and

and ![]() are

are ![]() matrices. Then, clearly,

matrices. Then, clearly,

![]() (4.7)

(4.7)

Also, as before, since ![]() is a positive semidefinite matrix it has non-negative diagonal entries, which implies the inequalities

is a positive semidefinite matrix it has non-negative diagonal entries, which implies the inequalities

![]() (4.8)

(4.8)

and

![]() (4.9)

(4.9)

It is left, therefore, to show that

![]() (4.10)

(4.10)

Observe that the matrices ![]() and

and ![]() are related by the equality

are related by the equality

![]() (4.11)

(4.11)

where

![]() (4.12)

(4.12)

and

![]() (4.13)

(4.13)

Moreover, since ![]() is a principal submatrix of

is a principal submatrix of![]() ,

,

![]() (4.14)

(4.14)

Hence from the Eckart-Young theorem we obtain that

![]() (4.15)

(4.15)

Corollary 16 Let ![]() be a given real symmetric

be a given real symmetric ![]() matrix with the spectral decomposition (1.2). Then the matrix

matrix with the spectral decomposition (1.2). Then the matrix

![]() (4.16)

(4.16)

solves the problem

![]() (4.17)

(4.17)

Corollary 17 Let ![]() be a given matrix, let the matrix

be a given matrix, let the matrix ![]() have the spectral decomposition (1.2), and let the matrix

have the spectral decomposition (1.2), and let the matrix ![]() be defined in (4.16). Then

be defined in (4.16). Then ![]() solves the problem

solves the problem

![]() (4.18)

(4.18)

5. Low-Rank Positive Approximants in the Schatten p-Norm

Let the diagonal matrix ![]() be obtained from the spectral decomposition (1.2). In this section we consider the problem

be obtained from the spectral decomposition (1.2). In this section we consider the problem

![]() (5.1)

(5.1)

Theorem 18 Let the matrix ![]() be defined in (1.6). Then this matrix solves (5.1)

be defined in (1.6). Then this matrix solves (5.1)

Proof. Let the matrices![]() , and

, and ![]() be defined as in the proof of Theorem 15. Then here it is necessary to prove that

be defined as in the proof of Theorem 15. Then here it is necessary to prove that

![]() (5.2)

(5.2)

where

![]() (5.3)

(5.3)

Let ![]() and

and ![]() be partitioned as in (4.6). Then from Lemma 8 we have

be partitioned as in (4.6). Then from Lemma 8 we have

![]() (5.4)

(5.4)

Now Theorem 4 and (4.8) imply

![]() (5.5)

(5.5)

while applying Mirsky theorem on (4.11)-(4.14) gives

![]() (5.6)

(5.6)

Finally substituting (5.5) and (5.6) into (5.4) gives (5.2). ![]()

6. Low-Rank Positive Approximants in the Trace Norm

Using the former notations, here we consider the problem

![]() (6.1)

(6.1)

Theorem 19 The matrix ![]() solves (6.1).

solves (6.1).

Proof. It is needed to show that

![]() (6.2)

(6.2)

where

![]() (6.3)

(6.3)

The use of Lemma 9 yields

![]() (6.4)

(6.4)

Here Theorem 4 and (4.8) imply the inequalities

![]() (6.5)

(6.5)

and Mirsky theorem gives

![]() (6.6)

(6.6)

which completes the proof. ![]()

7. Low-Rank Positive Approximants in the Spectral Norm

In this case we consider the problem

![]() (7.1)

(7.1)

Theorem 20 The matrix ![]() solves (7.1).

solves (7.1).

Proof. Following the former notations and arguments, here it is needed to show that

![]()

Define

![]()

Then, clearly,

![]()

Using Lemma 10 we see that

![]()

Now Theorem 4 and (4.8) imply

![]()

while Mirsky theorem gives

![]()

8. Unitarily Invariant Norms

Let the diagonal matrices ![]() and

and ![]() be defined as in Section 1, and let

be defined as in Section 1, and let ![]() denote any unitarily invariant norm on

denote any unitarily invariant norm on![]() . Below we will show that

. Below we will show that ![]() solves the problem

solves the problem

![]() (8.1)

(8.1)

The derivation of this result is based on the following assertion, which considers Ky Fan ![]() -norms.

-norms.

Theorem 21 The matrix ![]() solves the problem

solves the problem

![]() (8.2)

(8.2)

for![]() .

.

Proof. We have already proved that ![]() solves (8.2) for the spectral norm

solves (8.2) for the spectral norm ![]() and the trace norm

and the trace norm![]() . Hence it is left to consider the case when

. Hence it is left to consider the case when![]() . As before, the diagonal matrix

. As before, the diagonal matrix ![]() is defined in (4.2), and the matrices

is defined in (4.2), and the matrices ![]() and

and ![]() satisfy (4.4) as well as the partition (4.6). With these notations at hand it is needed to show that

satisfy (4.4) as well as the partition (4.6). With these notations at hand it is needed to show that

![]() (8.3)

(8.3)

Let ![]() be partitioned in a similar way:

be partitioned in a similar way:

![]() (8.4)

(8.4)

where

![]() (8.5)

(8.5)

and

![]() (8.6)

(8.6)

Then there are three different cases to consider.

The first case occurs when

![]() (8.7)

(8.7)

Here Theorem 3 implies the inequalities

![]() (8.8)

(8.8)

while from (4.11)-(4.14) and Mirsky theorem we obtain

![]() (8.9)

(8.9)

which proves (8.3).

The second case occurs when

![]() (8.10)

(8.10)

Here Theorem 3 implies

![]() (8.11)

(8.11)

while Theorem 4 and the inequalities (4.8) give

![]() (8.12)

(8.12)

which proves (8.3).

The third case occurs when neither (8.7) nor (8.10) hold. In this case there exist two positive integers, ![]() and

and![]() , such that

, such that

![]() (8.13)

(8.13)

and

![]() (8.14)

(8.14)

Now Lemma 11 shows that

![]() (8.15)

(8.15)

A further use of (4.11)-(4.14) and Mirsky theorem give

![]() (8.16)

(8.16)

and from Theorem 4 and (4.8) we obtain

![]() (8.17)

(8.17)

Hence by substituting (8.16) and (8.17) into (8.15) we get (8.3). ![]()

The fact that (8.3) holds for ![]() means that the inequality

means that the inequality

![]() (8.18)

(8.18)

holds for any unitarily invariant norm. This observation is a direct consequence of Ky Fan dominance theorem. The last inequality proves our final results.

Theorem 22 The matrix ![]() solves (8.1) in any unitarily invariant norm.

solves (8.1) in any unitarily invariant norm.

Theorem 23 Using the notations of Section 1, the matrix

![]()

solves (1.1) in any unitarily invariant norm.

9. Concluding Remarks

In view of Theorem 14 and Mirsky theorem, the observation that ![]() solves (8.1) is not surprising. However, as we have seen, the proof of this assertion is not straightforward. A key argument in the proof is the inequality (8.15), which is based on Lemma 11.

solves (8.1) is not surprising. However, as we have seen, the proof of this assertion is not straightforward. A key argument in the proof is the inequality (8.15), which is based on Lemma 11.

Once Theorem 22 is proved, it is possible to use this result to derive Theorems 15-18. Yet the direct proofs that we give clearly illustrate why these theorems work. In fact, the proof of Theorem 15 paves the way for the other proofs. Moreover, as Corollary 17 shows, when using the Frobenius norm we get stronger results: In this case we are able to compute a low-rank positive approximant of any matrix![]() .

.