Exploring the Association between Adult Attachment Styles in Romantic Relationships, Perceptions of Parents from Childhood and Relationship Satisfaction ()

1. Introduction

The impact which early experience has upon the development and maintenance of adult relationships is an enduring issue in developmental psychology and one which is of theoretical and clinical interest. This study will explore possible connections between perceptions of childhood experiences with parents, attachment styles in romantic relationships, and relationship satisfaction.

According to attachment theory [1] , the quality of early interactions between the child and their primary caregiver has a significant impact on the child’s subsequent psychological and interpersonal functioning throughout the lifespan. This theory is based on the premise that attachment security develops when the caregiver is perceived as being responsible and caring whereas attachment insecurity results when the caregiver is perceived as inconsistent in their responses and availability [2] . Importantly, it is believed that as a result of these early interactions, the child develops mental representations or internal working models of attachment which act as a guide for perceptions and behaviours in subsequent relationships. Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters and Wall [3] initially distinguished between three styles of attachment in infancy: secure, anxious/ambivalent, and avoidant. The anxious/ambivalent child is characterised by uncertainty regarding the love of their attachment figure while the avoidant child tends not to seek contact with the caregiver, appearing self-reliant. Main and Solomon [4] incorporated a fourth category, disorganised attachment, to account for children who displayed contradictory behaviours towards their caregiver. While the focus of this early research was on the mother-child interaction, subsequent research has examined the link between the quality of infant and adult attachment relationships [2] .

1.1. Methodological Approaches

Longitudinal studies have provided the strongest evidence for the continuity of attachment styles from childhood to adulthood [5] . Importantly, research has shown that working models of attachment while resistant to change, are subject to revision over time as a result of new experiences or an unstable relationship environment [6] [7] .

Two main approaches to assessing attachment-related cognitions in adulthood have emerged. The first approach centres on the use of attachment interviews to measure internal representations of attachment experiences [8] . The use of the Adult Attachment Interview [AAI; 9] is considered the gold standard when assessing such representations [10] . One disadvantage of the AAI, however, is that it requires extensive professional training before it can be administered and scored [11] . The second approach taken in a number of studies is the use of retrospective self-report questionnaires [12] . These measures rely on participants’ memories of parents during childhood and these accounts most likely reflect constructions or projections rather than accurate reports of early parental behaviour [13] . However, as Miga et al. [8] highlights, while interview techniques have proven to be very valuable, individuals’ explicit and consciously-reportable expectations about close relationships are also likely to have vital meaning in understanding social behaviour.

1.2. Attachment Styles in Romantic Relationships

It has been suggested that adult attachment in the context of romantic relationships serves an evolutionary, adaptive objective that is comparable to the parent-infant relationship (Feeney, 2008). Hazan and Shaver’s [12] preeminent work explored romantic love as an attachment process. Through the construction of self-report questionnaires, they found that the three different styles of attachment, as proposed by Ainsworth et al. [3] , help explain personality differences in experiences of romantic relationships. In essence, participant’s perceptions of the quality of their relationship with both parents during childhood were significantly associated with their attachment style to others in adulthood [12] .

In one aspect of their study, Hazan and Shaver [12] used an adjective checklist in which participants had to choose adjectives to describe their parents as they remembered them from childhood. Findings revealed that participants who were securely attached in their romantic relationships tended to describe their parents more positively, as well as the parents’ relationship as warmer, than did insecurely attached participants. In particular, secure participants were much more likely to describe their childhood relationships with parents as responsive, affectionate, caring and accepting than insecurely attached participants, who tended to describe this early relationship as cold and rejecting [12] [14] . Those with an anxious/ambivalent attachment style were also found to be more likely to describe their parents as inconsistent or unfair [12] . Similar findings were also replicated in other earlier studies using self-report questionnaires [15] [16] . Such research shows that securely attached individuals have a tendency to report positive perceptions of early family relationships [16] -[18] . On the other hand, anxious-ambivalent participants were found to be more likely to perceive early parental support as inconsistent, while avoidant participants were more likely to report being separated from their mother during childhood and to be distrustful of others [15] [16] .

1.3. Theoretical Issues in Attachment Research

Despite the importance of Hazan and Shaver’s [12] theory, numerous criticisms have emerged, particularly for their use of a three-category model of attachment. Subsequent research has stressed how avoidant individuals differ to the extent to which they displayed anxious and avoidant qualities [19] . Importantly, Bartholomew and Horowitz [20] later developed a two dimensional model of attachment in which four styles are defined. Most notably, they distinguished between two forms of avoidant attachment: avoidant-fearful and avoidant-dismissive. An avoidant-fearful style is characterised by both high avoidance and anxiety and by negative models of the self and others. Avoidant-dismissing individuals are characterised by high avoidance and low anxiety. While they have a positive model of the self, they have a negative evaluation of others as depending and needy, perhaps reflecting their discomfort with intimacy [21] . Anxious-preoccupied individuals are characterised by high anxiety and low avoidance, view themselves as unworthy and are preoccupied with the need to be accepted by others [20] [21] . These four relational styles have been found to show continuity over the lifespan [11] . More advanced measures of adult attachment are being used in current research, such as The Experiences in Close Relationships Scale (ECR) designed by Brennan et al. [19] , which was developed following a large-sample factor-analytic study that incorporated all known self-report measures in a single analysis. It works by assessing two underlying dimensions: attachment related anxiety and avoidance.

To date, there has been limited attachment research examining how the differential roles played by the mother and father may impact on individual differences in attachment mental representations [22] . Over the past few years, studies have incorporated this aspect into research on adult attachment styles [14] [23] . Roisman, Collins, Sroufe and Egeland [24] also demonstrated that young adults’ states of mind regarding their current romantic relationship are both associated with the quality of their romantic relationships and were rooted in attachment experiences with primary caregivers in childhood. Together, the results of earlier and more recent research provides strong evidence for the association between childhood relationships with parents, at least how they are constructed in memory, and the quality of later adult relationships [13] .

1.4. Attachment Style and Relationship Satisfaction

Since the preeminent work of Hazan and Shaver [12] , research concerning the influence of adult attachment on relationship satisfaction has demonstrated how secure attachment is positively associated with the quality of romantic relationships while insecure attachment is negatively associated with relationship satisfaction [25] -[27] . Earlier studies have demonstrated that secure relationships are characterised by commitment, high levels of trust, interdependence and satisfaction [15] [16] [28] . In particular, Feeney and Noller [16] found that avoidant participants were more likely to report never to have been in love than secure participants. Secure participants also tended to have longer relationships than anxious-preoccupied participants and were less likely to experience divorce [16] . More recent research using different measures also provide empirical support for the link between secure working models of attachment and the likelihood of experiencing more positive relationships [29] [30] .

1.5. The Present Study

The aim of this study is to investigate the possible connection between adult attachment styles in the context of romantic relationships, perceptions of parents from childhood and relationship satisfaction in a sample of young adults (18 - 39 years). Importantly, a key developmental task during this phase of life centers on establishing long-term, intimate relationships. In light of this, such research is important considering, as Florsheim [31] notes, romantic relationships are failing at an alarming rate as evident with the dramatic increases in the rates of singleparent families, separation, divorce, as well as relationship violence. Furthermore, dissatisfaction within relationships can lead to stress and to the development of clinical problems [32] . Therefore, such research has important practical applications for family therapy and clinical psychology [25] . Attachment research is heavily rooted in scientific theory and the combined use of old and new attachment measures in this study is unique. Furthermore, this research adds to existing literature by assessing perceptions of both parents and incorporating a measure of relationship satisfaction thereby addressing an aspect of attachment research which previous studies have neglected to explore in detail. The current study hypotheses are as follows:

Hypothesis 1: Males and females will differ in terms of their attachment style.

Hypothesis 2: Types of attachment in adulthood will be closely related to perceived early attachment experiences with parents.

Hypothesis 3: Adults involved in a current romantic relationship, compared to adults without a current relationship, will be differentiated as far as their attachment styles are concerned.

Hypothesis 4: In terms of current romantic relationships, secure adult attachment styles will be positively associated with relationship satisfaction, while insecure adult attachment styles will be negatively associated with relationship satisfaction.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

Participants consisted of 153 university students and 69 members of the general population, 177 (78%) of which were female and 50 (22%) were male, with an age range of 18 - 39. Of these participants, 207 (91.2 %) classified themselves as heterosexual, 8 (3.5%) as gay or lesbian, 9 (4%) as bisexual and 3 (1.3%) participants did not report a sexual preference. Of the 227 participants, 152 (67%) were currently involved in a romantic relationship at the time of the study, whereas 75 (33%) were not. Of these, 46 (30.3%) had a relationship for less than a year, 68 (44.7%) from 1 to 4 years, and 38 (25%) for 5 years and above.

2.2. Materials and Methods

Participants completed an online questionnaire which consisted of four sections. The first section contained questions pertaining to demographic information, such as age, gender, occupational status, relationship status, duration of relationship, and sexual orientation.

2.2.1. The Experiences in Close Relationships Scale-Revised (ECR-R)

The ECR-R [33] assessed participants’ attachment style in romantic relationships. This is a widely used selfreport measure of romantic attachment. It is comprised of 36 questions related to feelings of emotional security and intimacy in relationships. The scale measures two major dimensions of attachment in the context of close romantic relationships: anxiety (18 items) and avoidance (18 items). Participants indicated their agreement to the statements on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “Strongly Disagree” to “Strongly Agree”, with a neutral response option in the middle. Statements which assess attachment anxiety include “I often worry that my partner doesn’t really love me” and “my romantic partner makes me doubt myself”. Statements which measure attachment avoidance include “I prefer not to show a partner how I feel deep down” and “I prefer not to be close to romantic partners.” Low scores indicate secure attachment while high scores indicate emotional insecurity and difficulties with intimacy. The ECR-R has excellent reliability: in a meta-analysis, α coefficients were reported to be near or above 0.90, and test-retest coefficients were reported to be between 0.50 and 0.75 [34] .

2.2.2. Adjective Checklist

The adjective checklist devised by Hazan and Shaver [12] was used to ask participants to describe their parents and their parent’s relationship as they remembered them from childhood. Participants were first asked to choose adjectives that best described how their mother behaved towards them during childhood. Participants were then asked to choose adjectives to describe their father as they remembered him from childhood. Participants were then asked to choose adjectives that best described their parent’s relationship with each other, as they remembered it from childhood. The adjective checklist used for the description of the mother and father included 38 adjectives such as loving and unresponsive. Participants were also asked to describe their parent’s relationship using 12 adjectives such as affectionate and distant. While this is not a standardised measure, the results produced in Hazan and Shaver’s study have been conceptually replicated by other researchers using this instrument [14] [16] .

2.2.3. Couples Satisfaction Index (CSI)

The four-item format version of the CSI [35] measured participants’ satisfaction in their current romantic relationship. Participants were asked to rate their agreement with four statements using a 6-point Likert scale for one question and a five-point likert scale for three questions. The CSI was developed using item response theory and meta-analyses found the average reliability of the measure to be moderately high, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.940 [36] .

2.3 Procedure

The survey was developed using the computer software programme, Qualtrics [37] . Participants were primarily recruited through snowball sampling via the social media site, Facebook, where they were provided with brief information about the study and a link which directed them to the detailed information sheet, consent form, and the Qualtrics questionnaire. The study was advertised on Facebook pages which were dedicated to the target population. Facebook was a beneficial means of collecting data as it is hugely popular among young adults and it is the most frequently used online social networking website with 52% of its users accessing the website daily [38] . The heads of some schools in University College Dublin were also contacted via email to recruit more participants. Individuals were informed that participation was voluntary and that they had the right to withdraw at any time up until the data were collected, as data were completely anonymous and unidentifiable. Each participant needed approximately 15 minutes to complete the questionnaire. Participants were provided with details of the proposed aims of the study, possible risks regarding their involvement and contact details of helplines in case they were affected by the study.

3. Results

3.1. Data Screening and Cleaning

A total of 280 responses were recorded on Qualtrics but only 227 participants were utilised for the purpose of this study (see Figure 1).

Due to the disproportionate number of females compared to males, a random sample of females (N = 50) was compared to full sample of females (N = 177) and as there were no differences with respect to mean scores among key variables in this study, the full sample of females was used in the analysis for greater statistical power [39] .

3.2. Reliability Analyses

The two subscales of the ECR-R and the CSI demonstrated high reliability as they had a Cronbach’s alpha greater than 0.75 (see Table 1) [40] .

3.3. Preliminary Analyses

Table 2 provides a summary of the range as well as mean scores, standard deviation, skewness and kurtosis of the scales used in this study. As the scores for skewness and kurtosis are between +1 and −1 for each scale, the distribution can be treated as normal [41] .

3.4. Attachment Style

Participants were categorised into one of four attachment styles (secure, dismissing, fearful or preoccupied) according to the scores they obtained on the two ECR-R subscales, anxiety and avoidance. This was achieved by assigning participants to groups on the basis of the median of each dimension [51] . If participants’ anxiety score was less than 44 and their avoidance score less than 43, they were assigned to the secure group. If participants’ anxiety score was less than 44 and their avoidance score was greater or equal to 43, they were assigned to the dismissing group. If participants’ anxiety score was greater or equal to 44 and their avoidance score was greater or equal to 43, they were assigned to the fearful group. If participants’ anxiety score was greater or equal to 44 and their avoidance score was less than 43, then they were assigned to the preoccupied group. Analysing the responses to the ECR-R scale revealed that 30.4 percent of participants had a secure attachment style, 16.3 percent of participants had an avoidant-dismissing attachment style, 35.2 percent had an avoidant-fearful attachment style, and 18.1 percent had an anxious-preoccupied attachment style (see Figure 2).

3.4.1. Hypothesis One

Hypothesis one stated that males and females would differ in terms of their attachment style. The majority of males (40%) were found to have an avoidant-fearful attachment style whereas equal numbers of females were classified as secure (32.8%) and avoidant-fearful (33.9%) (see Table 3). Chi-square tests and the method of standardised residuals were carried out to examine the association between gender and attachment style and a significant association was not found, X2(3, N = 227) = 2.45, p > 0.05.

3.4.2. Hypothesis Two

Hypothesis two stated that adult attachment styles would be closely related to perceptions of parents from childhood. In order to examine this association, Chi-square tests were carried out across the 38 adjectives used

Table 1 . Cronbach’s Alpha analyses for each of the variables under investigation.

Table 2. Summary of Descriptive Analyses for the ECR-R and the CSI.

Figure 2. Frequencies and percentages of the four attachment styles.

Table 3. Frequencies and percentages of attachment style as a function of gender.

Note: X2(3, N = 227) = 2.453, p > 0.05.

to describe the mother and father. Standardised residuals (SR) greater than +/− 2.00 indicate a significant departure from the expected outcome. In order to control for type 1 error when conducting multiple comparisons, Benjamini and Hochberg’s (1995) rough false discovery rate was used and the level of significance was measured at below 0.025. This is a less conservative procedure with greater statistical power than the Bonferrroni correction [42] .

Adjectives for the Mother Securely attached participants were more likely to perceive their mother as respectful (SR = 3.2), confident (SR = 2.3), sympathetic (SR = 2.4), responsible (SR = 1.9) and flexible (SR = 2.2) but less likely to describe her as unpredictable (SR = −2.1), troubled (SR = −2.2), sad/depressed (SR = −2) or inconsistent (SR = −2.5). Avoidant-fearful participants were less likely to describe their mother as happy (SR = −2.9) and more likely to describe her as unpredictable (SR = 2.7), sad/depressed (SR = 2.2) and inconsistent (SR = 2.8). However, a number of these chi-square analyses (rejecting, weak, responsive, abusive, selfish, unfair, cold, hostile and immature) had expected counts less than five and therefore these results must be treated with caution (see Table 4).

Adjectives for the Father Participants with a secure attachment style tended to describe their father as happy (SR = 3.00), respectful (SR = 2.6), fair (SR = 2), sympathetic (SR = 2.5), understanding (SR = 2.2) and attentive (SR = 2.1). Those with an avoidant-fearful style were more likely to describe their father as cold (SR = 2.5), troubled (SR = 2.3), abusive (SR = 2.4), unfair (SR = 2.2), disinterested (SR = 2.5) and inconsistent (SR = 2.4), and less likely to perceive him as being respectful (SR = −2.6), happy (SR = −3.00), confident (SR = −2.1) caring (SR = −1.9), and affectionate (SR = −2.1). However as the chi-square test for attachment style and the adjectives abusive, rejecting, intrusive, weak, and nervous had counts less than 5 in 50% of cells, these findings must be interpreted with caution (see Table 5).

The Parental Relationship Chi-square analyses also revealed that secure participants were less likely to describe their parents’ relationship during childhood as troubled (SR = −2.00) or strained (SR = −2.4). Participants with an avoidant-fearful style tended not to describe the relationship as affectionate (SR = −2.1), supportive (SR = −2.4), caring (SR = −2.2) or good-humoured (SR = −2.1) but were more likely to describe it as unhappy (SR = 2.6), distant (SR =

Table 4. Summary of chi-square tests on adjectives used to describe the mother (N = 227).

Table 5. Summary of chi-square tests on adjectives used to describe the father (N = 227).

3.9), troubled (SR = 3.00) and strained (SR = 3.2). Those with an anxious-preoccupied attachment style were less likely to describe their parents’ relationship as distant (SR = −2.2). The chi-square test for attachment style and the adjective violent had counts less than 5 in 50% of cells; therefore this result must be treated with caution (see Table 6).

Positive and Negative Indexes To investigate whether the adjectives participants used to describe their parents had a positive or negative trend, two separate indexes were created, one for the positive and one for the negative adjectives. For the analysis, 2 × 4 non-repeated measures ANOVAs were conducted to investigate the effect of gender and attachment style on the two adjective indexes.

Positive Adjectives for Mother No significant interaction was found between gender and attachment style on the dependent variable, positive adjectives for the mother, F (3, 219) = 0.923, p > 0.05. As the higher effect was not significant but an ordinal interaction was observed, main effects can be reported. A statistically significant main effect of gender was found, F (1, 219) = 6.854, p < 0.05. Using Cohen’s (1988) criterion, the effect size was found to be small (partial eta squared = 0.03). Females (M = 9.12) used more positive adjectives to describe their mother than males (M = 7.12). A significant main effect for attachment style was also found, F (3, 219) = 4.009, p < 0.05. A small effect size was also observed (partial eta squared = 0.05). Post-hoc comparisons using the Scheffe test indicated that the secure group (M = 11.03) differed significantly from the three other groups: dismissing (M = 7.89), fearful (M = 7.29) and preoccupied (M = 8.15).

Negative Adjectives for Mother No significant interaction was found between gender and attachment style on the dependent variable, negative adjectives used to describe the mother, F (3, 219) = 0.159, p > 0.05. A significant main effect for attachment style, but not gender, was found with respect to negative adjectives used to describe the mother, F (3, 219) = 4.17, p < 0.05. A small effect size was observed (partial eta squared = 0.05). However, as the graph depicts a disordinal interaction, the main effects cannot be taken at face value (see Figure 3). The Scheffe post hoc test indicated that participants with an avoidant-fearful attachment style used more negative adjectives to describe their mother (M = 3.61), compared to securely attached participants (M = 1.67).

Positive Adjectives for Father No significant interaction was found between gender, attachment style on the dependent variable, positive adjectives used to describe the father, F (3, 219) =1.126, p > 0.05. An ordinal interaction means the main effects can be reported. A significant main effect was found for gender, F (1, 219) = 5.982, p < 0.05. However, a large

Table 6 . Summary of chi-square tests on adjectives used to describe the parental relationship (N = 227).

Figure 3. Mean scores for negative adjectives for mother based on gender and attachment style.

effect size was observed (partial eta squared = 0.27). Looking at the means, females (M = 8.453) used more positive adjectives to describe their father than males (M = 6.635). A significant main effect was also found for attachment style, F (3, 219) = 6.506, p < 0.05). A moderate effect size was found (partial eta squared = 0.082). Scheffe post hoc tests revealed that secure participants (M = 10.29) used significantly more positive adjectives to describe their father than those classified as avoidant-dismissing (M = 7.43) or avoidant-fearful (M = 5.78).

Negative Adjectives for Father No significant interaction was found between gender and attachment style on the dependent variable, negative adjectives used to describe the father, F (3, 219) =.658, p > 0.05. However, a significant main effect for attachment style was found, F (3, 219) = 7.098, p < 0.05. A moderate effect size was observed (partial eta squared = 0.089). However, the graph revealed a disordinal interaction and therefore examining the results alone may be misleading (see Figure 4). Post-hoc tests analyses revealed that those classified as avoidant-fearful (M = 3.51) used significantly more negative adjectives to describe their father than those classified as secure (M = 1.62) or avoidant-dismissing (M = 1.70).

Positive Adjectives for Parental Relationship No significant interaction was found between gender and attachment style on positive adjectives used to describe the parental relationship, F (3, 219) = 0.733, p > 0.05. However, a significant main effect for attachment style was found, F (3, 219) = 6.485, p < 0.05. A moderate effect size was observed (partial eta squared = 0.082). Again, a disordinal interaction was observed (see Figure 5). Scheffe post-hoc analyses revealed that those classified as avoidant-fearful (M = 2.36) used significantly less positive adjectives to describe their parental relationship than those classified as secure (M = 4.26) or anxious-preoccupied (M = 4.12).

Negative Adjectives for Parental Relationship No significant interaction was found between gender, attachment style and negative adjectives used to describe the parental relationship, F (3, 219) = 0.891, p > 0.05. A significant main effect for attachment style was found, F (3, 219) = 9.5, p < 0.05, with a moderate effect size (partial eta squared = 0.12) and a disordinal interaction (see Figure 6). Scheffe post-hoc analyses found that those classified as avoidant-fearful (M = 1.78) used more negative adjectives than did those classified as secure (M = 0.57) or anxious-preoccupied (M = 0.56).

3.4.3. Hypothesis Three

Hypothesis three stated that adults involved in a current romantic relationship, compared to adults without a current relationship, would be differentiated as far as their attachment styles are concerned. The majority of secure participants (94.2%) were involved in a romantic relationship at the time of the study whereas over half of avoidant-fearful participants (57.5%) were not involved in a romantic relationship (see Table 7).

A Chi-square analysis revealed a statistically significant association between attachment style and the existence or not of a romantic relationship, X2 (3, N = 227) = 45.88, p < 0.05. Participants categorised as secure in their attachment style were significantly more likely to be involved in a romantic relationship (94.2%) (SR = 2.8). There was no statistically significant association between the existence of a romantic relationship and gender,

Figure 4. Mean scores for negative adjectives for father based on gender and attachment style.

Figure 5. Mean scores for positive adjectives for parents’ relationship based on gender and attachment style.

Figure 6. Mean scores for negative adjectives for parents’ relationship based on gender and attachment style.

3.4.4. Hypothesis Four

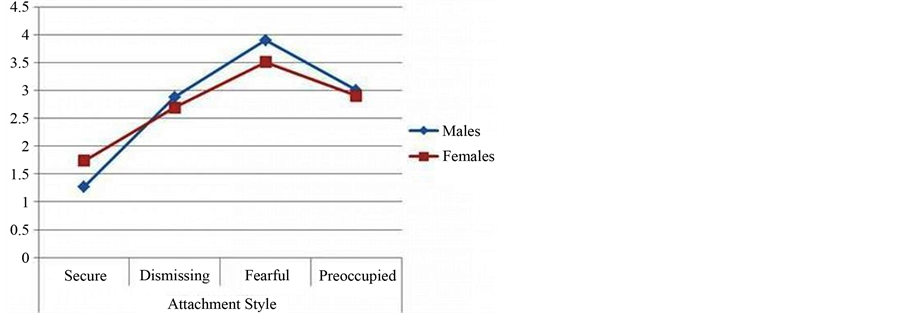

In order to examine the relationship between attachment style and relationship satisfaction, a 2 × 4 non-repeated measures ANOVA was conducted. No significant association was found between gender and attachment style on the dependent variable relationship satisfaction, F (3, 143) = 1.12; p > 0.05. A significant main effect was observed for attachment style with respect to relationship satisfaction, F (3, 143) = 15.01, p < 0.05. However, the effect size was large (partial eta squared = 0.24). The graph depicts a disordinal interaction (see Figure 7). Scheffe post hoc tests suggest that secure participants (M = 22.05) tend to be the most satisfied in their relationships whereas avoidant-fearful participants are the least satisfied (M = 16.73) (see Table 8 for a summary of all the two-way Anovas conducted).

Table 7. Frequencies and percentages highlighting the presence or not of a romantic relationship according to attachment style.

Table 8. Summary of two-way ANOVAS (gender * attachment style) on variables under investigation.

Figure 7. Mean scores for relationship satisfaction based on gender and attachment style.

4. Discussion

The present study sought to explore the association between adult attachment styles in romantic relationships, perceptions of parents from childhood, and relationship satisfaction. The results suggest that those who are securely attached in their romantic relationships are more satisfied and perceive their parents in a more positive light when reflecting on childhood than insecurely attached participants, especially those in the avoidant-fearful category.

The first hypothesis, which stated that males and females would differ in terms of their attachment style, was not supported. The majority of males were classified as avoidant-fearful, a finding similar to previous research [14] , while females tended to be classified as either avoidant-fearful or secure. Gender differences have been found with respect to avoidant attachment, with the tendency for males to engage in an avoidant-dismissing style and females to engage in an avoidant-fearful style [20] [43] [44] . Another unexpected finding in the present study is the relatively low percentage of securely attached males and females which is contrary to previous research [12] this finding has emerged in other studies examining young adults [14] .

Hypothesis two which stated that adult attachment styles would be closely related to perceptions of parents from childhood, as evident in the adjectives they used to describe them, was supported. Participants with a secure attachment style used more positive adjectives to describe their mother, father, and their parents’ relationship. More specifically, they tended to describe their mother as confident and sympathetic and their father as fair, understanding, and attentive. In contrast, participants with an avoidant-fearful attachment style used more negative adjectives to describe their parents. For example, they tended to describe their mother as unpredictable and inconsistent, their father as troubled and disinterested, and their parents’ relationship as unhappy. These results correspond with previous research, which suggests that those who are securely attached in adult romantic relationships are more likely to perceive the early relationship with their parents in a positive light, whereas those with an avoidant attachment pattern tend to view it negatively [16] [18] . In Carranza and Kilmann’s [45] study, for example, females classified as avoidant-fearful tended to use characteristics describing their father as distant and their mother as absent.

Hypothesis three which stated that adults involved in a current romantic relationship, compared to adults without a current relationship, would differ in terms of their attachment styles was supported. The majority of secure participants were involved in a romantic relationship at the time of the study, whereas over half of avoidant-fearful participants were not. This corresponds with previous research which states that those with a secure attachment are willing to get close to others, have a higher sense of self-worth, and value others more highly [14] . On the other hand, individuals categorised as avoidant-fearful often regard themselves as unworthy and tend to avoid close relationships with others in order to protect themselves against anticipated rejection [20] . In the present study, however, more avoidant-dismissing participants than expected were involved in a romantic relationship. This is surprising considering such individuals tend to avoid close relationships by maintaining independence in order to protect themselves against disappointment [20] . An explanation for this finding may be that dismissing individuals who are committed in relationships often remain independent and self-sufficient, allowing themselves to avoid unwanted intimacy or they may choose romantic partners with a similar attachment style [46] .

Finally, hypothesis four which stated that secure attachment would be positively associated with romantic relationship satisfaction, while insecure attachment would be negatively associated with relationship satisfaction, was supported. Secure participants were found to be more satisfied in their current relationship than the three insecure attachment styles perhaps reflecting their capacity to provide and experience love, care and support [12] [16] . Avoidant-fearful participants were the least satisfied with their relationship. Research suggests that more avoidant and anxious individuals are characterised by a variety of dysfunctional relationship behaviours, thoughts and feelings which lead them and their partners to be less satisfied [2] . Gender differences were not observed with respect to attachment style and relationship satisfaction which compliments previous research [25] [27] [28] .

Theoretical Issues

The variability in the approaches taken to measure attachment may account for the inconsistency of the results, especially concerning the frequency of specific attachment orientations. Early research used a three-category model of attachment (e.g. Hazan & Shaver, 1987), before the four attachment styles derived from Bartholomew and Horowitz’s [20] model became prominent. Using this model combined with Brennan et al.’s [19] anxiety and avoidance dimensions, more recent research assessed attachment style as being continuous rather than categorical in nature [47] [48] . While these approaches are all highly related, attachment classifications across measures do not always correlate [8] [21] . Both the categorical and dimensional approaches are meaningful ways of looking at attachment and one has not been found to be more powerful than the other [49] [50] . While the dimensional approach may be statistically advantageous [51] the classification system distinguishes between various ways of manifesting attachment insecurity and this has led to the recognition of the preoccupied attachment style, which is regarded as the strongest single predictor of later psychopathology [50] .

The current study has numerous strengths worth considering. Firstly, the topic is heavily rooted in empirical research and while the theory is not new, research has validated its clinical importance. The use of standardised scales is a key strength, particularly the use of the ECR-R which has been regarded as one of, if not the, most appropriate self-report measure of attachment currently available [52] . Furthermore, incorporating a reliable measure of relationship satisfaction adds to previous research which has just examined connections between early parenting and attachment styles in adulthood (e.g. [12] [14] ). The inclusion of participants who were not students enhanced the generalizability of the findings and this was important considering much research on romantic relationship attachment has focused solely on university students [12] [14] [16] . On a theoretical level, attachment research has emphasised the role of the mother with some exceptions examining the role of the father [12] [13] [15] [16] . This research adds to the literature by assessing perceptions of both parents and the parental relationship. This is important considering research has increasingly recognised the vital role played by the father in early life [53] [54] .

The limitations of the current study provide directions for future research. Self-report measures are highly subjective and they increase the possibility of social-desirability biases [55] . Retrospective self-reports of childhood may not always be reliable due to the fallibility of human memory [13] [56] . However, attachment theory is not only concerned with the relationship as it can be observed from outside but particularly how it can be inferred from the individual’s internal perspective on the relationship, therefore self-report measures of attachment are useful [49] .

Furthermore, it is important to acknowledge the possibility of bidirectional influences: the quality of both the current romantic relationship and current relationship with parents may shape how participants’ perceive early child-parent relationships [13] [57] . In the present study, it is not possible to make inferences about the causal direction of the relationships under examination. Therefore, future research could benefit from the use of longitudinal studies which may offer insight into how early parenting behaviours act as predictors of later relationship functioning while also monitoring changes in an individual’s internal working model of attachment over time [13] [21] . Furthermore, while Hazan and Shaver’s [12] Adjective Checklist was useful for gaining an insight into more general positive or negative perceptions of parents in childhood, future research could incorporate the use of the AAI to provide a more in-depth examination of participants’ mental representations of early attachment experiences with parents [22] .

An additional limitation is the disproportionate number of females compared to males in the present study. This was addressed by comparing a random sample of females and the full sample of females to check for similarities. Nevertheless, a larger and more representative sample of males may have produced different results. An extreme variability with regard to male-to-female ratios is evident in research using web-based surveys [58] . In a meta-analysis which examined romantic attachment research using web-based surveys, only 24% of participants were male which may indicate that males are less interested in online questionnaires about romantic relationships [58] . Furthermore, gender differences in romantic attachment tend to be more pronounced in research using community and college samples and less evident in web-based surveys which may also explain the current findings [58] . In order to accurately examine gender differences in romantic attachment, perhaps large demographically representative samples would be more appropriate [58] . The current study did not collect specific demographic information on participants. While this study was looking at a general association between adult attachment and perception of parents in childhood, future research could explore the impact of other variables on attachment relationships, such as socio-economic factors for example, which has been linked to relationship quality [59] .

Finally, as this study only catered for traditional families whereby a mother and father were present throughout childhood, future research should examine attachment within single-parent and other non-traditional families [13] . The impact of specific life events, such as parental divorce, on attachment orientations in adulthood are important to consider as those who experience this tend to be less securely attached, report greater relationship problems and are more likely to have an avoidant-fearful attachment style [60] .

The present study compliments previous research which suggests that there is a connection between perceptions of one’s early parental relations and attachment in adult romantic relationships. This study expanded current research on attachment styles to incorporate relationship satisfaction. In this sample of young adults, those with a secure attachment style perceived their parents in a much more positive light than those with an avoidant attachment style. Furthermore, those classified as secure were more likely to be involved in a romantic relationship at the time of the study, and reported being more satisfied. Fearful-avoidant participants were less likely to be in a romantic relationship, and those that were tended to report experiencing dissatisfaction in their relationships.