Improvements of Nutrition Behavior Fitness and Body Fatness with a Short-Term after School Intervention Program ()

1. Introduction

The prevalence of childhood obesity has been increasing in developed [1] and developing [2] countries. Data from the 2008-2009 Brazilian Household Survey indicated that approximately 33.5% of children (ages 5 - 9 years) and 20.5% of adolescents (ages 10 - 19 years) are above the weight considered healthy by the World Health Organization (WHO). Obesity prevalence increased from 2.3% to 14% (ages 5 to 9 years) and 0.5% to 5% (ages 10 to 19 years) between 1974-1975 and 2008-2009 [3,4]. Obese children are more likely to become obese adults [5,6] and are at a higher risk of developing adverse health conditions such type 2 diabetes mellitus, the early-onset metabolic syndrome, subclinical inflammation, dyslipidemia, coronary artery diseases [2], and psychosocial outcomes [7]. The metabolic syndrome rates in Brazilian childhood are available from regional studies and range from 4% to 42.4% [8-12].

The increasing prevalence of obesity is due to complex interactions between genetic and environmental factors such as dietary intake and physical activity. The most important factors underling the obesity epidemic are high caloric intake coupled with limited energy expenditure [13]. Both obesity and excessive abdominal adiposity predispose children to be unfit in abdominal strength/ resistance and aerobic resistance. Excess of body adiposity increase the likelihood of poor trunk flexibility [14]. Moreover, low physical fitness is associated with higher sedentary behavior illustrated by the TV time [15].

Because of the increasing public health importance of childhood obesity, many intervention studies have been conducted in developed and developing countries. These studies performed interventions during school time [16- 20], or after school hours [21-26], aiming various target outcomes such as nutrition education [18,20], physical activity [16,21-23] or a combination of these approaches [17,19,24-26].

A recent meta-analysis showed that school-based interventions that contain a physical activity component may be effective in helping to reduce BMI in children [27]. Therapeutic lifestyle changes and maintenance of regular physical activity are the most important strategies in managing childhood obesity [2,28]. The present study aimed to describe the intervention effects of nutrition and physical activities offered as an after school short-term outcomes of healthy nutrition practices, fitness and lowering fatness.

2. Methods

This quasi-experimental study was conducted with a convenience sample of 59 caucasian children (first to fifth grade students), aged 7.7 ± 1.4 years old (52.5% girls) from a private school of Sao Paulo State, Brazil. The study’s aims and methods were presented to children’s parents at the beginning of the academic year. Parents gave written consent for their children to participate in the study. Participating children were free of motor disorders that could impede participation in the physical activity education program. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of School of Medicine of Sao Paulo State University—UNESP/Botucatu (protocol 579/2006).

The study was designed to be a school-based 12-week intervention, including a nutritional education and a physical activity program in which the children engaged in twice a week for 60 minutes. This program has been implemented in the school since 2005. It has been developed by the Nutritional and Exercise Metabolism Centre (CeMENutri) of the UNESP-Medical School which is a multi-professional teaching and research centre located in Botucatu city, a middle size city (in 2010, there were 127,328 inhabitants), in a middle western part of Sao Paulo, a Brazilian southeast state.

2.1. Measurements

Anthropometric measurements, including weight (kg), height (cm), waist circumference (WC) were obtained according to standard protocols (WHO 1995). All the measurements were assessed the week before and immediately after the intervention program. Body Mass index was calculated for all the children. The diagnosis of overweight was based on the BMI equal to or higher than the 85th percentile and lower than the 95th percentile, and obesity was considered a BMI equal to or higher than the 95th percentile [28]. Waist circumference values and percentiles were classified according to McCarthy et al. (2001) [29].

Fitness tests including flexibility and abdominal strength/ resistance were measured according to standards protocols [30].

2.2. Intervention

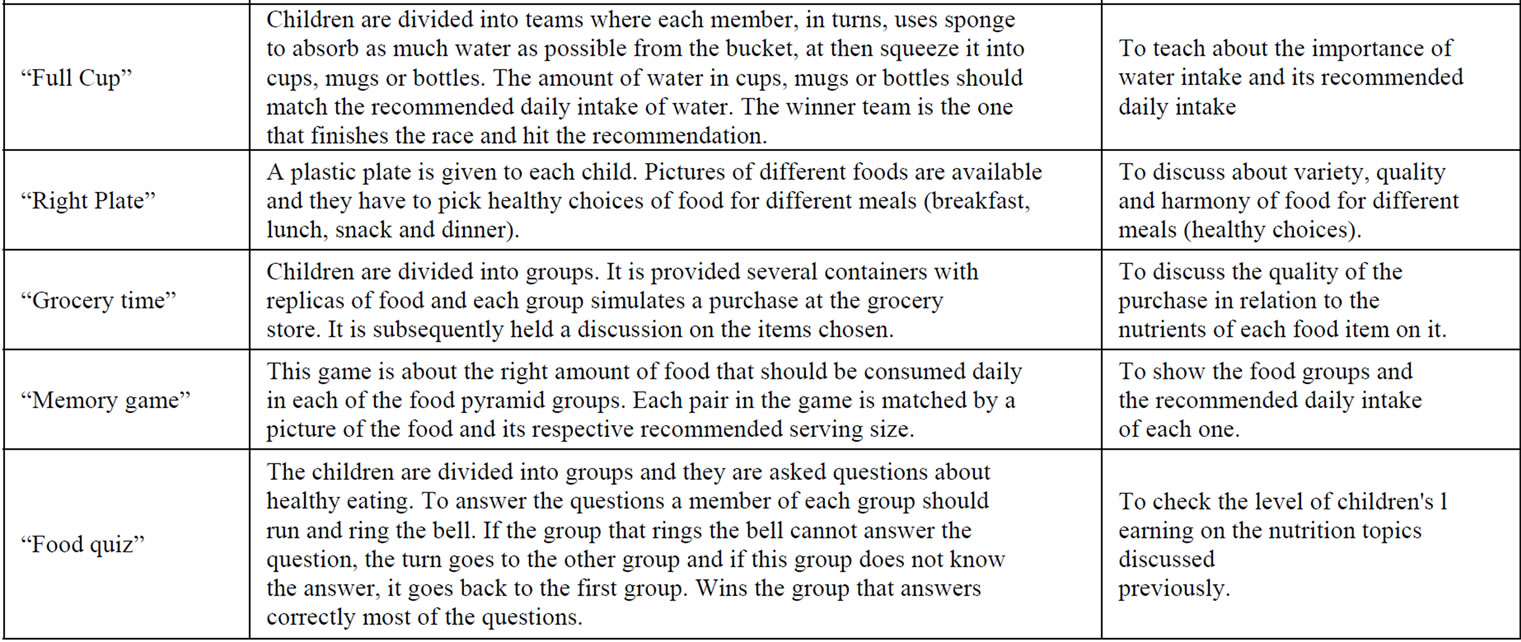

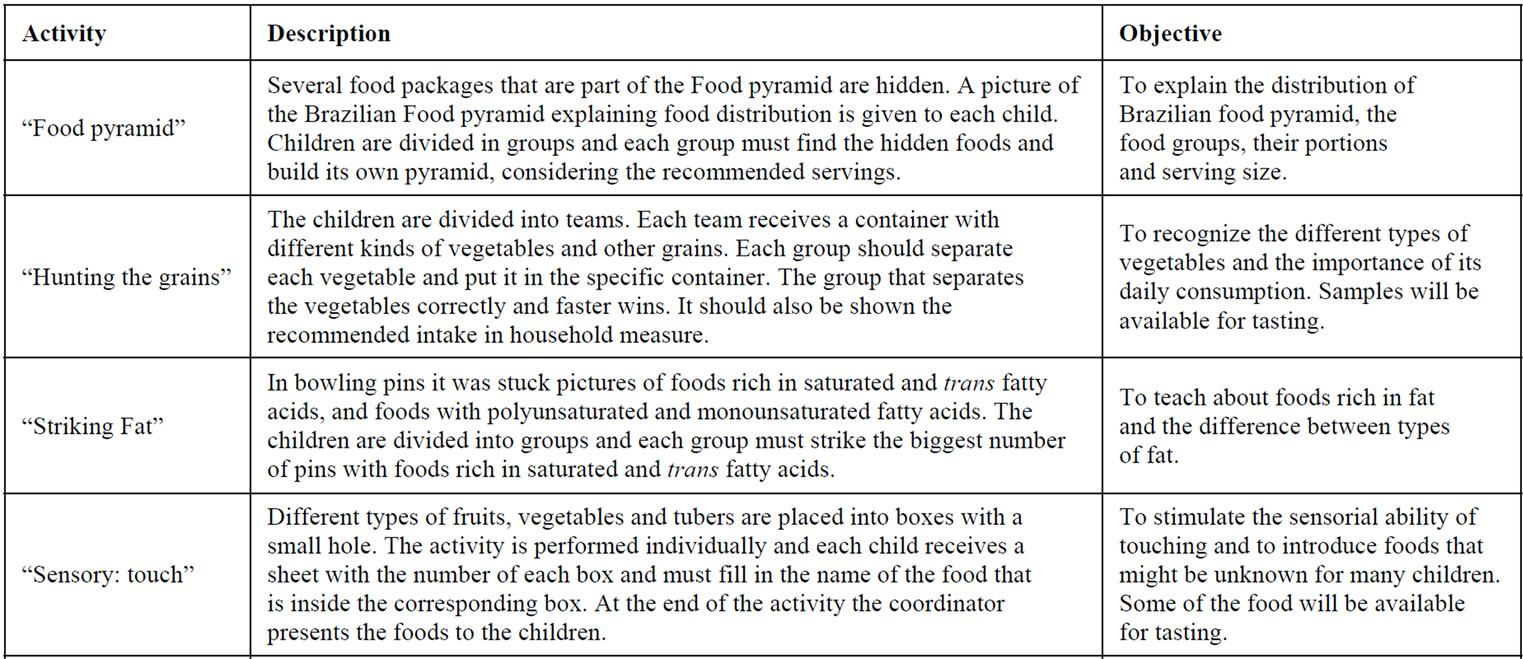

The nutrition education and physical activity program were conducted both by certified professionals. The program consisted of two 60-minutes section per week, during 3 months. The intervention aimed to improve knowledge, attitudes and eating habits of the children along with increasing daily exercise. The program included lectures and information about human body, the importance of energy and nutrients, consequences of physical inactivity and high energy intake. It also included cooking classes, games and discussions about healthy/unhealthy food and drink, composition of food and drink, and the children’s nutritional pyramid (Figure 1). The nutritionist had presented the nutrition and activity material in an engaging, interactive manner to encourage the children’s participation. After each nutrition education session a healthy snack was provided for every child. Healthy cooking workshops were performed by a certified nutritionist where nutrition education focused on the increasing intake of fruits and vegetables and whole grain products, and the decreasing intake of foods rich in fat, salt and sugar. A healthy meals/recipes book was developed to achieve children’s needs and provided to the parents. The physical activity program combined games for outdoors and activity games, looking for coordination and flexibility improvements.

2.3. Qualitative Questionnaire

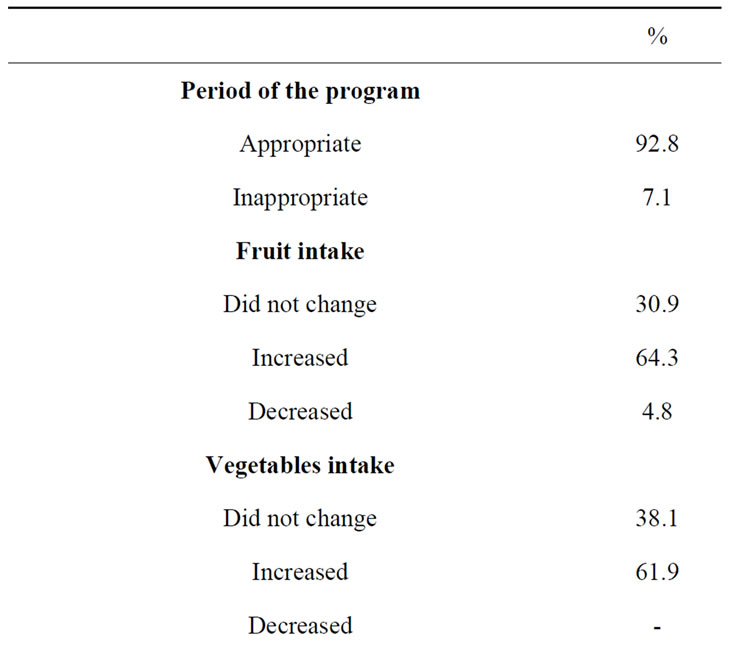

All parents were contacted and requested to complete questionnaire after the 12-week intervention program. Parents were queried about the project content and changes in children’s eating behavior (Figure 2).

2.4. Statistical Analysis

The analyses were performed by using SAS, version 9.1. The data were described as mean ± SD. Sample normality was tested by means of the Shapiro-Wilk test. Difference between baseline and after 12-week intervention of

Figure 1. Activities performed during the program.

Figure 2. Questionnaire sent to parents after the intervention program.

variables was analyzed by paired student’s t test after. The effect between categories of BMI, WC, flexibility, strength/abdominal resistance and aerobic resistance was analyzed by means of chi-square test. The results were discussed based on the level of significance of p < 0.05.

3. Results

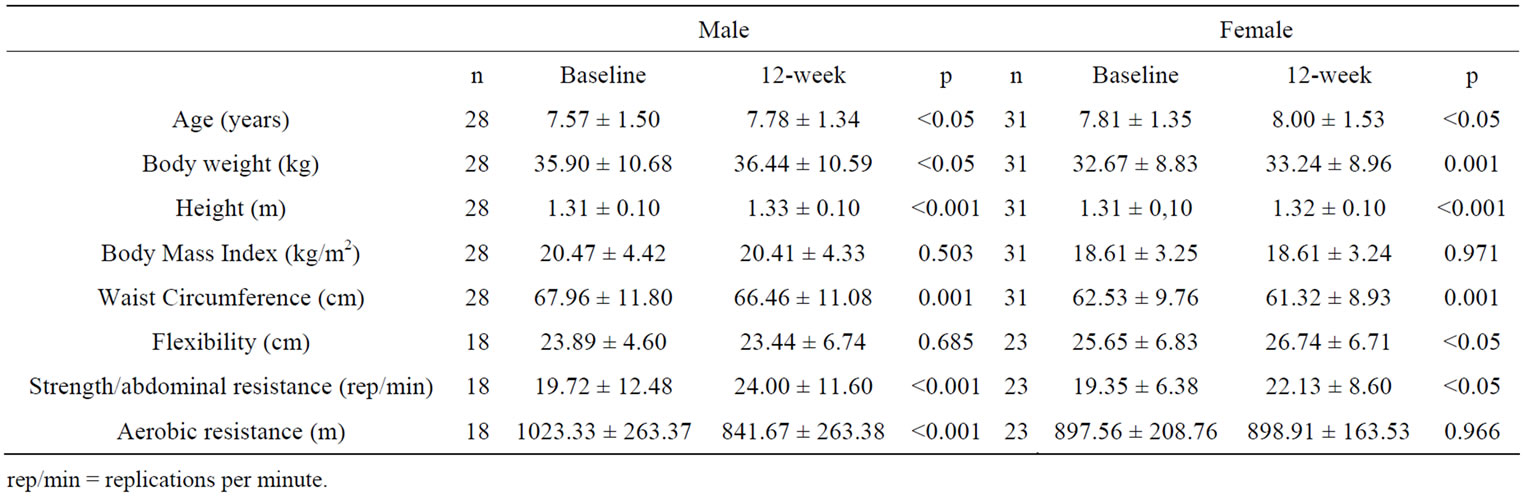

The characteristics of the study population at baseline and after the intervention are shown in Table 1. Mean height was significantly higher by 2.0 cm among boys and 1.0 cm among girls after a 12-week intervention. Body weight was also higher by 0.54 kg among boys and 0.57 kg among girls. Although mean values of BMI remained the same after the intervention it was noticed a decrease in the prevalence of obesity of among the children. Waist circumference was significantly lower and abdominal strength improved after participating in the intervention program. It was also noticed that flexibility improved among girls and aerobic resistance decreased among boys after 12 weeks of intervention.

There were no statistically significant differences in the nutritional status and fitness of children after the intervention. However, the prevalence of obesity decreased in 3.4%, abnormal waist circumference decreased in 6.8%, and abnormal strength/abdominal resistance decreased in 17% (Table 2).

Analysis of children’s food behavior after the intervention program showed an increase in the intake of fruits (64.3%), vegetables (61.9%), and water (52.0%). Overall, 83.3% of the children changed eating behavior according to the questionnaire responded by the parents (Table 3).

Table 1. Characteristics of the study population at baseline and after a 12-week intervention.

Table 2. Nutritional status and fitness of the study population at baseline and after a 12-week intervention.

Table 3. Qualitative questionnaire about child’s eating behavior after the intervention program.

4. Discussion

The purpose of our study was to document the results of a short-term school-based intervention program on lifestyle (nutrition and physical activity) of Brazilian children. The improvement of fitness and eating behavior led to a decrease in the prevalence of obesity, suggesting that it may be possible to control/reduce this problem in schools. The program not only decreased the prevalence of obesity but also improve children’s fitness by increasing abdominal strength and physical resistance. Moreover, our intervention program improved children dietary quality by increasing the intake of fruits, vegetables and water. We believe that the parental involvement in this program played an important role in child’s eating behavior changes as they were informed of the purpose of the study and were informed about their child’s nutrition status over time. Besides, parental involvement increases participation of children in the program and help children makes the right choices and planning a balanced meal. The implementation of this short-term after-school intervention was successful and well accepted by parents and children.

Many intervention programs promoting physical activity and healthy diet have been demonstrated to be effective in several countries [24,26,31-33]. Most interventions showed improvement in health knowledge and health-related behaviors, including consumption of lowfat diet, increase in fruits and vegetables intake, and more physical activity [31,34]. Our short term intervention program (12 weeks) was successful in reducing body fatness and improving fitness and eating behavior of school children. Some of studies we reviewed had a length of intervention ranging from four weeks to three years [21,23,26,32], yet evidences suggest that a short intervention period might be associated with better outcomes [21,23,35].

The prevalence of overweight and obesity in our study were higher in boys than in girls. After the intervention the prevalence of obesity decreased 3.8% in boys and 3.0% in girls. Small shifts in BMI may be more effective at a population level than simply reducing the prevalence of obesity [36].

Inadequate eating behavior and sedentary lifestyle predispose to childhood obesity. There are interactions of many factors that contribute to the obesogenic environments and affect children’s weight, such as individual factors, home influences, and school factors. Afterschool intervention programs that promote an open-air physical activity along with healthy cooking class replaces a time that would be probably spent by children in front of the television or playing with computer and video games.

This study had several potential limitations: the children’s group was not separately to meet their age-appropriated developmental and gender issue; the intervenetion were applied to a small number of children and thus may not be representative; lack of control group.

Despite of these limitations, out data shows successfully the efficacy of a multidisciplinary school intervenetion to reduce body fat and improve fitness and healthy eating behavior in children. The increased prevalence of childhood obesity is an indicator of public health problem. High-risk screening and effective health educational should be priority especially in developing countries.

5. Conclusion

Our study showed that a school-based intervention program focused on nutritional education and physical activity program promote waist circumference reduction, improve fitness and healthy eating behavior. This intervention program would be feasible and replicable in others schools around the country.

6. Acknowledgements

Pró Reitoria de Pesquisa da UNESP and FUNDUNESP, for providing funds for the publication fee.