The Virtuous Circle of Corporate Social Performance and Corporate Social Disclosure ()

1. Introduction

In recent years, particularly in highly developed economies, concerns about social issues have taken more and more momentum among stakeholders. At the same time, companies have increased their attention towards socially responsible behaviors in order to catch an additional opportunity for improving the interaction with the internal and external environment.

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) received a wide number of definitions since its first recognition, from an academic point of view, given by the seminal work of Bowen [1] . The result is a lack of universal definition, but, at the same time, the opportunity to interpret the CSR from multiple perspectives [2] . Among the others, one of definitions commonly accepted dates back to the proposition of Carroll [3] , according to which the social responsibility of a business belongs to the economic, legal and ethical expectations that society has of the organizations at a given period of time. This definition follows the one proposed by Davis [4] that identifies a social responsible company in the organization accomplishing social benefits, together with the profit seeking, in consideration and in response to issues which are beyond the narrow economic, technical and legal requirements of the firm. Later on, another commonly used proposition refers to the European Community Commission [5] that considers the CSR as a concept whereby companies integrate social and environmental concerns in their business operations and in their interactions with their stakeholders on voluntary basis. More recently, other Authors [6] defined corporate social responsibility as the actions taken by firms that further the needs or goals of a stakeholder group or of a larger societal collective. So, in their vision corporate social responsibility belongs to a voluntary behavior which encompasses actions that go beyond firm’s legal requirements.

Summing up all these definitions we notice the increased relevance of CSR within management studies. In particular, what seems clear, at a theoretical level, is that company’s attitude to generate profit is not the only behavior that matters, or the only responsibility of managers [7] . As a consequence, nowadays, firms have the need to measure and communicate their economic and financial performance as well as their social performance.

The corporate social performance (CSP) has become a relevant topic of the ongoing wider debate on corporate social responsibility [3] [4] [8] . Studies in this field began in the 70s and are still the focus in a lot of theoretical and empirical contributions [9] [10] [11] [12] [13] . Following Wood [14] , the CSP can be considered as “a business organization’s configuration of principles of social responsibility, processes of social responsiveness, and policies, programs and observable outcomes as they relate to the firm’s societal relationship”. Therefore, a complete assessment of CSR performance includes principles, processes and outcomes. From this perspective, CSP embraces: how actions taken on the behalf of a company are driven by principles of social responsibilities; if processes put in place by the company are socially responsive; finally, what the observable outcomes are, in term of social and environmental benefits, of company’s actions.

Once companies have been involved in the assessment of social performance, then they need to use efficiently this information in a suitable way for corporate goals and stakeholders’ claims. So, the use of information on CSP includes its measurement and the communication within the organization and towards the external environments with which it interacts. In this way, what is defined as a voluntary corporate social disclosure (CSD) acquires relevance for managing CSR and its effects. At a theoretical level, CSD includes a wide range of different information on the activities and public image of corporation with respect to the natural environment, the community, the employees, the customers and the corporate governance [14] [15] [16] [17] [18] . It’s an important bridge between the increasing demand for sustainability and the demonstration of higher business sensitivity for social instances. However, the variety of information potentially included within CSD has asked different initiatives in order to systematize the contents of disclosure and to improve its capacity to be respondent to the needs of any given stakeholder group. These efforts include the ISO 14001, SA8000, ISO 26000, the United Nations Global Compact (UNGC) and Sullivan’s Global Principles [19] . The same objective was behind the work of The Coalition for Environmentally Responsible Economies (CERES) and the Tellus Institute. They developed the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) in 1997 to create an international standard for sustainability reporting. The goal is the achievement of better social performance communication and the opportunity of an effective comparison between companies. GRI Guidelines were for the first time issued in 2000, and, although other international standards, they still represent the most widely used reporting framework around the world [20] . In summary, all the mentioned standards aim at introducing a CSR language [21] or a common grammar of social reporting [22] .

On the basis of previous considerations, it is arguable that the CSP and CSD are definitely two key issues in the field of corporate social responsibility. However, when it comes to assess the relationship between social performance and social disclosure, scholars have not convergent positions, being apparently divided in two different perspectives. Indeed, on one hand, some researchers argue that corporate social performance impact on corporate social disclosure. On the other hand, there are several contributions where the theoretical and empirical approach is represented in the opposite way, that is the CSD affects CSP. As a consequence of this dichotomous approaches, there are some still open research questions, such as: is corporate social performance the driver of the corporate social disclosure? or, conversely, is corporate social disclosure the driver of corporate social performance? That is, which is the direction of the relation between CSP and CSD?

Therefore, drawing from the voluntary disclosure theory [23] [24] [25] , from sociopolitical perspectives such as the stakeholder theory [10] [26] [27] [28] [29] and the social legitimacy theory [30] [31] [32] [33] [34] , taking also into account the implications of the agency model [35] , the paper tries to shed a light on a better comprehension of the relationship between CSP and CSD. In particular, the aim of this study is the demonstration of a non one-way relation, but, rather, the existence of a mutual interference between the social performance and the social disclosure made by companies. On the operational level, this perspective subtends the opportunity for management to generate a virtuous circle which intercepts the capability to be responsive to social claims and the attitude to communicate actions and results of social initiatives. At the same time, on a theoretical level, this study aims at demonstrating that the main streams of studies on the relationship between CSP and CSD are not necessarily antagonists, since they may coexist in a unique and more exhaustive theoretical framework.

The paper falls into five sections, aside from introduction and conclusions. Section two reports the literature review which is divided in two subsections. The first section includes studies concerning the role of the CSP as a driver of the CSD and the second analyze studies where the CSD is seen as a driver of CSP. In the third section research hypotheses are presented. In Section 4 we describe data collection and methods. Finally, research findings are presented and discussed in the fifth section.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Corporate Social Performance as a Driver of Corporate Social Disclosure

In this section we analyze the main theoretical contribution in the field concerning the relation between CSP and CSD where the former represents a driver of the latter.

Voluntary disclosure theory, which is mostly based on several seminal works such as the ones of Grossman [36] , Milgrom [37] , Dye [38] and Verrecchia [39] , allows to focus on the information asymmetry between firms and its stakeholders. According to this perspective, firms would voluntarily communicate information on corporate social and environmental responsibility. The theoretical principle is that stakeholders, aware that firms have information that they lack, should interpret the non-disclosure as a deliberately decision taken by the firm and evaluate this circumstance in a negative way. The thesis is consistent with another assertion of voluntary disclosure theory which states that firms are more likely to disclose good performance and hide bad ones [23] . This is why good social performance often results in higher disclosure, with a greater adoption of quantitative measures of CSP, whereas bad performance is more likely to result in a silent behavior of the firm or in a lower disclosure in quality and quantity, in other terms, in a poor CSD.

Other studies concerning this direction of the relationship between CSP and CSD are based on the framework of the stakeholder theory and of the legitimacy theory. In the former perspective companies are seen in an incessant attempt to satisfy stakeholders expectations [10] [21] [40] . Therefore, firms may disclose their performance in order to communicate with stakeholders and so fulfill their claims [15] [16] [28] [41] [42] . Legitimacy theory, then, states that since firms are, and live in, a socioeconomic system, they need to improve constantly their reputation among clients, workers, communities, investors and others. In a broader view, companies need to fit better they can do with their micro and macro environment [43] . So, communicating the social performance, firms may improve the capacity to acquire legitimacy to their existence in the long term. Indeed, through the CSD tool, companies demonstrate that their values and activities are aligned with the value system of the socio-economic system in which they operate [31] [32] . In this sense, McGuire [44] stated that firms with a higher communication of social performance strengthen their rights of social citizenship which has multiple dimensions (economic, legal, ethical, philanthropic) as later noted by Carroll [45] [46] .

In addition to the theoretical perspectives mentioned above, some authors adopt agency theory [35] for investigating CSP as a driver of CSD. In case of separation between ownership and control, managers may act in an opportunistic way and agency costs, such as monitoring costs, bonding costs and residual loss, may arise. Once firms have better social performance this may result in a higher CSD, which is, in any case, a form of information asymmetry reduction as well as for financial voluntary disclosure [25] . Therefore, lower controlling costs may arise [47] [48] , with the opportunity to generate a potentially higher profitability and a lower risk condition. Both these factors, then, may impact on firm value, once the former increases the expected cash flows and the latter reduces the cost of capital [39] . Furthermore, financial benefits of CSD gain a significant importance if we look at the institutional investors like the Socially Responsible Funds (SRFs) that have increased their weight on the financial markets. Indeed, SRFs act in a condition of double agency [49] [50] being, on one hand, the principal of the firms in which they have invested, but, on the other hand, they are the agent of the social responsible private investors (saver). So, once firms disclose their social and financial performance, SRFs can do the same with the savers, by transferring to the management of investment portfolio the contribution offered by CSD to company value creation.

In conclusion, from the previous theoretical contributions, corporate social performance can be identified as a driver of corporate social disclosure (Figure 1).

By the way, consistently with Lindblom [32] , this relation may be either positive or negative, depending on management communication strategies. If manager intention is to inform stakeholders about the actual level of performance, then the relation will be positive; if managers try to manipulate stakeholders perceptions, then the relation can also be negative. In this latter case, we can find poor performance driving high disclosure because manager may act to create “noise” around the social performance in the

attempt to convince stakeholders that firms performance are aligned with their expectations [51] .

Confirming the existence of an open question, empirical findings give mixing results. Some Author provide a positive relation between CSP and CSD [52] [53] [54] [55] , other studies found a negative relation between CSP and CSD [56] [57] [58] [59] [60] , furthermore, in some other studies no relation has been found [61] [62] [63] . However, these mixing results may subtend not only the difficulty of demonstrating a unidirectional relationship, but also potential operational limits inherent these type of works, such as the adopted reporting media [64] , the method to measure both CSP and CSD and the sampling approach [58] [65] .

2.2. Corporate Social Disclosure as a Driver of Corporate Social Performance

About the CSD and the corporate social performance another body of studies tried to investigate the relationship between results and disclosure with a nexus of causality where is the latter the driver to the former. As known, firms nowadays suffer a growing pressure from the internal and external environment to behave in a social acceptable way. In this scenario, the corporate social disclosure becomes a tool used to communicate and control the social legitimacy of corporation. Therefore, assuming that CSD is faithfully reporting corporate social performance to firm stakeholders, both performance and disclosure can be seen as proxies of firm commitment to social legitimacy. Thus, the higher is the commitment, the higher would be the need for firms to communicate social performance and, subsequently, the higher would be the incentive to better perform in the future.

From this perspective, managers can adopt CSD to increase social performance in two ways: through a proactive and/or a passive approach. In the first case, managers use CSD proactively since they have the opportunity to systematize, analyze and control social performance. By monitoring the past results, managers can improve the next ones. In a more passive way, instead, the more firms disclose data and information about social performances, the more they will empower their stakeholders [51] . Stakeholders empowerment is often related to a higher social pressure on the firm which turns into a higher commitment of manager for improving social performances. Resource dependence theory [66] and the stakeholder theory suggest that in a similar context, where a company has to face a potential lack of resources and it has to interact with different or conflicting stakeholders claims, firms have the need to manage potential constraints that could be put in place by the most crucial stakeholders [67] . This is consistent also with the legitimacy theory, since firms, empowering stakeholders, may give them the opportunity to verify if the management policies fulfill or not the social contract [68] .

In addition, the nexus of causality between social disclosure and social performance can be read under the lens of the agency model. Managers opportunistic behavior is often linked to the attitude to sacrifice profits in order to gain personal advantage. Among other activities that managers could do to extract profit, there is the corporate social activity. From this perspective, CSD could give higher prestige to manager who is well ascertained as socially responsible, thus generating an incentive for improving corporate social performance which in turn will increase his personal advantage [69] .

The common denominator of the mentioned perspectives is the mitigating effect of CSD on information asymmetry. That is, the disclosure of social performance enhances the control attitude of the different parts involved. From a company’s view, managers have the opportunity to discover in what areas of CSR are hiding the strengths and the weaknesses of a company, consistently with the nature and the aims of an integrate reporting system which allows to control for financial and extra-financial performance. From the stakeholder side, the voluntary disclosure of social performance increases the information available for screening and eventually boycott companies with less sustainable business models. At the same time, on the basis of the salience of stakeholders, the reduction of information asymmetry and the consequent pressure can be translated in a higher incentive to do well by doing good. Finally, in a shareholder view, the measurement and communication of the outcomes of socially responsible initiatives may contribute to legitimate managers to act in a socially responsive way.

So, summarizing previous considerations, the CSD can be read as a driver for improving CSP (Figure 2).

3. Research Hypothesis

In this section we provide a theoretical model which is consistent with the purpose to integrate both the streams of research described in the previous literature review. Indeed, we think that is useful to join together the nexus of causality which assumes corporate social performance as a determinant of corporate social disclosure and the other one which assumes that corporate social disclosure is a determinant of corporate social performance. The interactive relationship assumed in our analysis, if demonstrated, will contribute to the recognition of a virtuous circle between CSP and CSD in the long run. In other words, assuming a not one-way relationship, we consider the two main theoretical positions about the question “on which drives which” between CSP and CSD, not anymore in an antagonist perspective, but in a complementary view.

As it has become widely accepted, Corporate social responsibility, as well as the economic and financial activities, needs to be measured and communicated. In our case, the measure of CSR is the corporate social performance previously defined. At the same time, the measure of its communication is the corporate social disclosure, understood as the quantity and quality of social performance communication. As the financial statements contribute to communicate the financial performance to various stakeholders, in the same way, the CSR report is a communication tool to shed light on the level of corporate social performance gained by the company in the different areas of its social responsibility.

Since the streams of research have significantly drown from the stakeholder theory, the resource based view, the agency theory and the legitimacy model, this study assumes that is possible to find a link between the two, apparently, divergent positions on the relation between CSD and CSP. The main link is the management of information asymmetry [70] in a context where the firm can be considered as a nexus of incomplete contracts, social and not, with stakeholders. The latter have different, and sometimes divergent, claims and salience [67] . Therefore, a company is called to manage the relation with its stakeholders in order to survive and improve its performance. In this perspective it’s possible to overcome the classical trade-off between social and financial performance, at least in the long run [71] [72] .

Once accepted that the two theoretical positions on the relationship between CSD and CSP may be read in an integrated way, also their conclusion may coexist. That is, the corporate social performance is a driver of corporate social disclosure, but in a continuum, corporate social disclosure may enhance future social performance. In particular, on one hand, the achievement of social performance can be translated into a greater potential alignment with the expectations of stakeholders, thereby encouraging a greater level of social disclosure. On the other hand, the communication of the company's current performance gives more information power to the stakeholders, making them better able to monitor the firm’s attitude to cope to its social responsibility with further initiatives. In addition, the CSR reporting may contribute to improve the internal control system of social performance, thus feeding from the inside the further efforts for the improvement of the management response to the requests of various stakeholders, including the needs of knowledge and the assessments of investors interested in corporate social responsibility. Therefore, assuming the mitigation of asymmetric information both internally and externally as the intangible link between CSP and CSD, the latter is both driven by and a driver of CSP.

In this regard, we are conscious that this non unidirectional relationship could not happen simultaneously. Rather, it implies a time lag between the occurrence of social performance and its communication, as well as between the latter and the incentive to improving the ability to be responsive respect to the different expectations of stakeholders.

In fact, the information on social performance need to be measured and processed within the reporting systems as well as the outcomes of this activity need to be communicated to and understood by the internal and the external stakeholders. In this model, the link between CSP and CSD may be improved over time, thanks to the experience in the reading and managing information on CSR programs.

Therefore, in order to demonstrate the non one-way relationship between social disclosure and social performance, this study refers to a concept previously adopted in other investigations [18] [50] [73] , that is the breadth of CSD. This last is understood as the capability of the corporate social reporting to cover a broad range of CSR themes in a stakeholder perspective. So, the greater the number of themes addressed within the social reporting, the greater the breadth of the CSD. In this way, the assumption of an interaction between CSP and CSD can be read, from one side, as the opportunity to improve the level of social disclosure thanks to high social performance, and, from the other side, as the incentive exerted by CSD on the management for improving corporate social results (Figure 3).

![]()

Figure 3. The non one-way relationship between CSP and CSD.

To sustain the theoretical framework of this study, that can be summarized as an interactive linkage between the amplitude of CSD and the level CSP, both the following hypotheses need to be confirmed:

H1. The corporate social performance at time “t” (CSPt) is a determinant of the breadth of corporate social disclosure at time “t + 1” (CSD-breadtht+1).

H2. The breadth of corporate social disclosure at time “t” (CSD-breadtht) is a determinant of corporate social performance at time “t + 1” (CSPt+1).

4. Data Gathering and Methods

The list of the sampled companies has been drawn from the Morningstar platform, since they are all participated by European Socially Responsible Funds (SRFs). For financial data and the measures of social performance, this study refers to Datastream and ASSET4-ESG, respectively. Moreover, the measurement of the level of social disclosure is based on the CSR-reports (also called “social reports”) published by the firms in the sample.

More specifically, drawing data from the portfolios of the European Socially responsible funds (SRFs) listed on the Morningstar platform in 2010, the empirical analysis is based on the CSD and the CSP of a sample composed by 80 firms all participated by SRFs. The followed approach is distinctive of this study. In fact, assuming a certification function of the SRFs, the empirical analysis is conducted on companies that are ascertained as socially responsible. On the basis of information provided by the Morningstar platform, we have built a cumulative portfolio stratified by industry. The cumulative portfolio has been organized by industries in a descending order, according to the number of SRFs participating in each company. Then, the weight of each industry within the cumulative portfolio has been calculated. Therefore, for each industry, given the availability of CSR reports published both in 2008 and 2009, the companies have been selected proceeding by a decreasing order in accordance with the frequency of the SRFs presence and cutting off the extraction when the weight of the industry in the sample is near to the percentage weight retained within the cumulative portfolio.

Given the theoretical framework, particularly important for this study is the measurement of CSD. The paper measured the CSD through the CSR reports, also called sustainability or social reports. So, according to previous surveys [17] [29] [48] [73] , the analysis of 160 CSR reports (report published in 2008 and 2009 for each of the 80 firms) has been based on six areas of disclosure which include different stakeholder perspectives such as: human resources, environment, community, customers, suppliers and corporate governance (see the appendix). These areas subtend a different number of themes that are the same adopted in previous investigations [18] [50] [73] . For each theme it has been detected if the company has made or not the disclosure during the time period 2008 and 2009. Through this process, it has been calculated a ratio between the number of themes reported and the total of themes assigned to any given area. Similar to other studies that have assessed the topic with self-constructed measure for CSD [17] [50] [73] [74] [75] , for each company an index called “CSD-breadth” has been calculated. The design of the index is consistent with previous studies [18] [50] [73] , aiming to measure the breadth of the CSD on the basis of the range of themes included within the CSR reports. Since the number of themes in a single area can be considered arbitrary, to mitigate this effect, the CSD-breadth is constructed as the sum of the six ratios referred to each area. Therefore, the global index CSD-breadth has been used to measure the level of CSD taking into account the structure (areas and themes) of the CSR reports.

Given the aim of the study, a second critical variable is represented by the corporate social performance (“CSP”). In this case, on the same time horizon 2009 and 2008, for each company we have gathered data from the dataset ASSET4-ESG, a global indicator of the social performance obtained as a sum of the single scores attributed by the dataset during the period 2009 and 2008 to the following areas: environment, human rights, corporate governance, customers and employment. It can be noted that the areas are consistent with the information domains assumed for the analysis of CSR reports.

Moreover, to complete the analysis, the study adopted several control variables. Empirical literature in the field of CSR found a correlation between the size of the firm and its disclosure of social performance. Authors found that the larger is the size, the higher the CSD [16] [48] [76] [77] [78] . This circumstance confirms that when firms dimension increases, management tends to disclose a wider range information, including the ones concerning social and environmental commitment. In our models we control for firms size by the log transformation of total sales.

Several studies argue that pressure coming from stakeholders on the CSD may also change in relation to the cultural and economic context in which the company is located [29] [79] [80] [81] . Differences in the CSD may be up to diversity between countries in terms of emphasis on the social and environmental issues. Distinguishing the contexts with a “stakeholder orientation” from the ones with a “shareholder orientation” [29] , we organized the sampled companies following the classification proposed by Hall and Soskice [82] that is already adopted in similar previous investigations [83] . So, consistently with the categories of Hall and Soskice, to control for a country effect, a dummy variable has been introduced (“Country”). It assumes value 1, if the sampled firm belongs to a Coordinated Market Economy (CME) and value 0 if the firm belongs to a Liberal Market Economy (LME). The first one is considered more stakeholder oriented, while the second one is assumed as more shareholder oriented.

Previous literature has investigated the impact of corporate financial performance (CFP) on better social performance. Even if it’s a controversial topic, following the study of Waddock and Graves [71] that identifies a virtuous circle between CFP and CSP on the basis of the slack resource theory, the study have controlled for the company’s profitability. In particular, this latter control variable has been measured through the return on investment (ROI).

Finally, considering the GRI as the more complete standard for the assessment and the communication of CSR initiatives, a dummy variable called “GRI” has been introduced. It assumes value 1 if the sampled firm adopted the Global Reporting Initiatives Standards, 0 otherwise. This variable has been measured on the basis of the disclosure standard applied by the firms for their social reports.

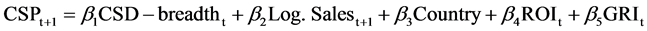

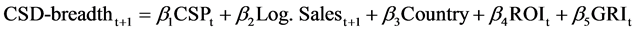

Therefore, given the variables described above, we run two OLS regression models that are formalized as follows:

Model (1)-Hypothesis H1:

Model (2)-Hypothesis H2:

As already explained, we state that corporate social performance at time “t” is a determinant of the corporate social disclosure at time “t + 1” (which disclose the performance obtained at time “t”) and that corporate social disclosure at time “t” (which disclose social performance obtained at time “t − 1”) is a determinant of corporate social performance at time “t + 1”. In our model we assume 2008 as time “t” and 2009 as time “t + 1”. The controlling variables are all measured at time “t”.

5. Results and Discussion

Descriptive statistics for the variables used in the study are displayed in Table 1, while the sample firms composition by industry is reported in Table 2.

Findings of the first model are showed in Table 3. The model, which has been controlled for the collinearity through the VIF test, is statistically significant as a whole and it shows an adjusted R squared of 38.6%. Thus the model explains mostly the forty percent of the corporate social disclosure variance.

The CSP predictor is 99% statistically significant and the beta is considerably high (0.485). For these reasons our first hypothesis (H1) is confirmed. However, this is not the only significant finding of model one. Indeed, corporate social disclosure seems to be positively correlated to firm profitability and country. Both these control variables are significant and positively related to the breadth of disclosure. So, in the first case, the higher is the return on investment at time t + 1, the higher is the CSD-breadth at time t. Moreover, firms belonging to countries more stakeholder oriented (CME) show a higher breadth of social disclosure than companies belonging to countries more

Source: author’s calculation on data collected from Data stream, Asset4-ESG and firm’s social reports.

![]()

Table 2. Sample composition by industry.

Source: author’s calculation on data collected from Morningstar platforms.

![]()

Table 3. Regression analysis with CSD-breadtht as dependent variable.

Source: author’s calculation on data collected from Data stream, Asset4-ESG and firm’s social reports.

shareholder oriented (LME). The other controlling variables, such as the GRI standard and the size are positively related to corporate social disclosure, but this relationship is not significant.

The results of the second model are represented in Table 4. The OLS is statistically significant as a whole and it has been controlled for the collinearity through the VIF test. The adjusted R squared is equal to 0.492, thus the regression explains almost half of the variance of the dependent variable. Moreover, the model shows that corporate social disclosure is a determinant of corporate social performance. In fact, the relationship between CSD and CSP is positive and significant at a 0.99% with a beta of 0.288. Therefore, also the second hypothesis (H2) is confirmed. In addition, we found significance in two controlling variables which are both positively related to corporate social performance. In particular, the adoption of the GRI affects the social performance as well as firm size which results to be a predictor of CSP. In the first case a better standard of measurement and communication of CSR seems to improve the efforts for better social performance. This last, then, is positively related to the size of the company, thus confirming that bigger companies are normally more involved in the compliance with CSR best practices.

Since both hypotheses are supported by the regression analyses, we can confirm our theoretical framework. In fact, an integrated reading of the analysis model shows that performance drives disclosure and disclosure drives performance. From one side better

![]()

Table 4. Regression analysis with CSP as dependent variable.

Source: author’s calculation on data collected from Data stream, Asset4-ESG and firm’s social reports.

performance are an incentive for a higher breadth conferred by firms to CSD. From another side a higher amplitude of CSR reporting, implying a stakeholder empowerment and the fostering of internal control systems, is a predictor of future better social performance. So, as previously argued, findings confirm that the two mentioned streams of theories need to be seen under the lens of their mutual relation. In this way, overcoming a unidirectional relationship, it’s possible to arrive at more complete understanding of the virtuous circle between the attitude to better perform in a social sense and the efforts finalized to mitigate the information barriers towards the stakeholders through an improved CSD (Figure 4).

![]()

Figure 4. The interaction over time between CSP and CSD.

If it is enacted, the virtuous circle may contribute to a sustainable competitive advantage in addition to a stronger right of citizenship which legitimizes company’s survival in the long run. This is consistent with the increasing interest that nowadays the community shows towards CSR themes and with the parallel increasing commitment of firms towards social issues.

6. Conclusions

The paper aimed to integrate theories concerning the relation between CSD and CSP in a unique theoretical framework. Previous literature investigates separately the capacity of corporate social performance to predict corporate social disclosure and the influence of corporate social disclosure on corporate social performance, generally following a unidirectional and alternative relationship. In our paper the two relations coexist in a model which assumes a time lag between the observed measures of CSP and CSD. We tested our model through the analysis of 160 CSR reports published in 2008 and 2009 by 80 firms participated by social responsibly funds listed on Morningstar Platform in 2010. The results of the empirical investigation well support the assumption of an interactive relationship between the level of social performance and the amplitude of voluntary social disclosure. That is, the higher the performance of the firm in the CSR areas, the higher the breadth conferred by the same firm to the CSD. Moreover, the higher capability of firm to cover a wide number of CSR themes in a stakeholder perspective with its CSD, results in a higher level of the expected social performance.

Obviously the paper has some limitations that are inherent this type of study. In particular, the first limit refers to the measurement of CSD. Secondly, the sample considers only companies participated by SRFs. So, if from one side this is consistent with the aim to look at firms that are CSR sensitive, form the other side the characteristic of the sampled companies could limit the universality of the model if referred to companies that are not backed by SRFs. However, this limitation is mitigated by the increasing diffusion of the compliance with CSR, especially if we refer to bigger companies like that included in this empirically study. Moreover, SRFs are also increasing their weight on the equity market [83] .

Notwithstanding the mentioned limits, what the study demonstrates has both theoretical and managerial implications. In the first place, findings justify the increasing attention of managers towards the capability of the company to be responsive in addressing the social and environmental claims. In the second place, the efforts in the CSR areas need to be measured in order to enact two main effects. From one side there is the need to better select in which areas and towards which stakeholders a company has to allocate its resources. This is a big issue especially after the last financial crisis which has left on field more severe financial constraints. From the other side, there is the need to reduce the informative barriers between the firm and its stakeholders. This means a higher competitive pressure, but, at the same time, an increased opportunity for the company in legitimating its operational activities. Finally, even if the link with financial performance is sometimes controversial or not linear [72] [84] , a positive effect of CSD on CSP could be translated in a better profitability for the firm, thanks to a higher efficiency and a lower exposure to the risk of social costs and boycotts in the future [85] [86] . Therefore, the virtuous circle between the CSP and the breadth of CSD can be extended to the potential effect on the financial performance of the firms. The study of this multiple relation could be the target of future venues of investigations, and further researches could expand the sample towards companies that are not participated by SRFs. Moreover, additional measures of CSD breadth could be applied through the content analysis of CSR reports.

Appendix Areas and Themes of Disclosure

Submit or recommend next manuscript to SCIRP and we will provide best service for you:

Accepting pre-submission inquiries through Email, Facebook, LinkedIn, Twitter, etc.

A wide selection of journals (inclusive of 9 subjects, more than 200 journals)

Providing 24-hour high-quality service

User-friendly online submission system

Fair and swift peer-review system

Efficient typesetting and proofreading procedure

Display of the result of downloads and visits, as well as the number of cited articles

Maximum dissemination of your research work

Submit your manuscript at: http://papersubmission.scirp.org/

Or contact me@scirp.org