Nonlinear Change in Refractive Index and Transmission Coefficient of ZnSe:Fe2+ at Long-Pulse 2.94-μm Excitation ()

1. Introduction

Single-crystal Fe2+-doped ZnSe is currently the subject of extensive studies since it demonstrates capability of being used as an effective laser medium for the spectral region ~4.0 - ~5.0 µm [1] -[11] . The laser property stems from the presence of Fe2+ centers, created after doping ZnSe with Fe, which possess of a broad resonant-ab- sorption band spanned from ~2.5 to ~4.5 µm, relevant for pumping by conventional lasers based on Er3+-doped materials [3] [5] [8] [12] -[15] . This band, easily saturated by pulsed radiation, also allows the use of ZnSe:Fe2+ as a passive Q-switch cell for ~3-µm Er3+-doped lasers [16] -[18] . Much efforts were made to clarify the physics of ZnSe:Fe2+ behind its functioning as a laser or Q-switch element. However certain gaps still exist in the knowledge of some of the featuring ZnSe:Fe2+ properties. For instance, the nonlinear-optical characteristics of ZnSe:Fe2+ were under scope in a very few works and limited by the studies of resonant-absorption saturation at ~3-µm pumping [16] [19] -[22] , with the main result being the estimates for the ground-state absorption (GSA) cross-section σ12. Meanwhile, there is no―as far as we know―any data about the mechanisms and values of nonlinear refractive-index Dn in ZnSe:Fe2+ at ~3-µm excitation. The other problem, insufficiently addressed to date is quenching of ZnSe:Fe2+ fluorescence, in terms of Fe2+ lifetime reduction in regard to temperature and Fe2+ concentration, at in-band excitation [1] -[3] [5] [19] - [21] .

In the present work, the single-beam Z-scan technique [23] was employed to inspect the nonlinear part of refractive index and nonlinear transmission of ZnSe:Fe2+. This technique was successfully applied from the 90-ies for studying versatile nonlinear materials possessing different kinds of amplitude and phase optical nonlinearities. Usually, Z-scan experiments comprise a set of single-beam measurements, allowing determination of the quantities that attribute the nonlinear response of a medium to excitation. The ZnSe:Fe2+ samples we deal in the present study have been obtained via the diffusion method, allowing embeding Fe2+ centers into the ZnSe matrix in high concentration [20] [24] [25] ). In Sections II and III, we study experimentally the nonlinear changes in transmission and refractive index of ZnSe:Fe2+ at sub-mJ pulsed 2.94-µm probing by means of the Z-scan technique. [Note that the sole work [19] , where the Z-scan technique was applied for ZnSe:Fe2+, was targeted at a study of its nonlinear transmission only, not Dn.] In Section IV, we model the problem of propagation of pulsed ~3-µm radiation through ZnSe:Fe2+, where the two key nonlinearities are addressed, stemming from saturation of the resonant transition 5E→5T2 (Fe2+) and from light-induced heating. In Section V, we discuss the results and reveal the main laws that obey the studied optical nonlinearities, inherent to this type of ZnSe:Fe2+ excitation. The conclusions are formulated in Section VI.

2. Experimental Setup and Samples

Setup: The experimental setup is shown in Figure 1.

We used as probe the output beam of a flash-lamp pumped actively Q-switched (using an electro-optical LiNbO4 cell) Er3+:YAG laser (1), oscillating in the regime of giant pulses at a wavelength of 2.94 mm. The laser operated at a low repetition rate, 0.5 Hz (a single laser pulse per a flash-lamp shot), ensuring minimal thermal effects in the cavity and, correspondingly, high stability of the output parameters (pulse energy and pulse width). Pulse duration tP was fixed (290 ns) in experiments. The laser beam’s spatial distribution was made (using an intra-cavity diaphragm,) to be TEM00 mode and its polarization was set (by the active element’s wedging) almost linear (~1:100). A small portion of the beam was deflected by a CaF2 plate (2) for monitoring the pulses with a pyro-receiver (3), while its major part was passed in between “folded” Al-reflectors (4) and (5) and focused by a CaF2 lens (7) (with a focal distance of 30 cm) into a ZnSe:Fe2+ sample (8). The beam waist in the focus was measured to be w0 = 75 mm. Neutral filters (6) placed in front of the lens allowed varying pulse energy, delivered to the tested sample. Energy of a single pulse, transmitted by the sample, was measured by a pyro-receiver (12), identical to the reference one (3) (note that decay time constants of both the pyro-receivers exceeded 1 ms, which ensured the measured parameter being pulse energy). Open- and closed-aperture Z-scans were obtained by translating the sample along Z-axis around the beam waist, Z0 (±2.5 cm). When measuring closed-aperture Z-scans, a circular pinhole (9) with a diameter of ~0.6 mm (transmission, ~3%) was placed in front of receiver (12), whereas when measuring open-aperture Z-scans the pinhole was removed from the beam. Neutral filters (10) and a scattering plate (11) were set in front of receiver (12) to avoid its saturation and to homogenize the beam’s distribution on the receiver’s sensitive head. ZnSe:Fe2+ samples were placed on a motorized stage, movable along the laser beam. Each experimental Z-scan point was obtained after averaging over 10 laser pulses, ensuring accuracy of the measurements better than 5%. Signals from the pyro-receivers were recorded using an acquisition board, arranged in the KAMAK’s standard, equipped with a PC; the PC also controlled Z-shifting of the stage with a ZnSe:Fe2+ sample. In advance to Z-scan experiments, signals from the pyro-receivers have been calibrated by a

calorimeter (placed in the scheme instead of the sample). Pulse energy (Ep) was preserved to be less than 0.58 mJ in the experiments, since at higher pulse energies optical breakdown sporadically happened when ZnSe:Fe2+ samples (especially the one with the highest Fe2+ concentration) were passed through the focus.

The nonlinear (pulse-energy dependent) changes in ZnSe:Fe2+ transmission coefficient and refractive index were determined from the measurements of open- and closed-aperture Z-scans, T0(Z) and T1(Z)/T0(Z) (hereafter Z is the longitudinal coordinate of a sample at its translating along the optical axis). A signal from pyro-receiver (12) in the absence of pinhole (9) gave us, after dividing by input energy (a signal from pyro-receiver (3)), open-aperture Z-scan transmittance. Closed-aperture Z-scan transmittance was obtained by a similar way but with the pinhole placed in front of receiver (12), by means of dividing the measured transmission by the T0(Z)- value. For an absorbing medium (our case), Z-scans T0(Z) and T1(Z)/T0(Z) contain the information about the nonlinear transmission (absorption) and refractive index, respectively. In the present study, we paid most of attention to monitor the nonlinear changes in transmission and in refractive index (Dn) of ZnSe:Fe2+ in function of incident pulse energy (Ep).

Samples: Samples of ZnSe:Fe2+ were obtained at room temperature through the diffusion process under conditions for the thermodynamic equilibrium of solid ZnSe, solid Fe, and SZnSe?SFe?V vapors in evacuated quartz ampules at a He atmosphere; see e.g. Refs. [22] [25] . The diffusion time was variable when getting the ZnSe:Fe2+ samples, which gave rise to different average concentrations of Fe2+ dopants; see Table 1. During the process, opposite sides of pristine single-crystal ZnSe plates with almost parallel faces and thicknesses of ~1.5 mm were subjected to Fe-diffusion. The three studied samples (hereafter samples 464, 422, and 474) were fabricated at the following temperature and diffusion exposure times: 857˚C/241 h (sample 464); 858˚C/216 h (sample 422); 912˚C/192 h (sample 474). After diffusion has been completed, the ZnSe:Fe2+ plates were polished at both sides, resulting in ~1-mm thick final samples, with total thicknesses of the areas enriched with Fe2+-centers being 150 - 250 µm. Note that these thicknesses are much less than the confocal parameter’s value, z0~0.6 cm, which validates the “thin sample” approximation [23] , used at modeling Z-scans experiments.

The linear (“small-signal”) transmission spectra of the samples were recorded using a spectrophotometer; the results are demonstrated in Figure 2, for a 500 - 3200-nm region. It is seen that all samples demonstrate a smooth absorption band centered at ~3 mm, characteristic for the Fe2+ (transition: 5E→5T2) centers. No other features were detected in the spectra, apart an increase of attenuation in the VIS, originated from the ZnSe matrix’s band-gap. It is seen that concentrations of Fe2+ centers (proportional to extinctions in the ~3-µm band) differ by orders of value in the samples.

3. Experimental Results

In experiments, ZnSe:Fe2+ samples were placed almost perpendicularly to the probe beam’s propagation. The examples of nonlinear transmittance of samples 464, 422, and 474, measured without a pinhole in front of receiver (12) (i.e. open-aperture Z-scans T0(Z)), and normalized ratio of the nonlinear transmittances, measured with and without the pinhole (i.e. closed-aperture Z-scans T1(Z)), are shown by symbols in Figure 3(a)-3(c) and Figure 3(d)-3(f), respectively. In the figure, we demonstrate the data for the maximal pulse energy at the samples incidence (Ep = 0.56 mJ), whereas the data obtained after proceeding similar Z-scans, measured at smaller pulse energies, are collected in Figure 4(a)-4(b). It is seen that substantial transformations in transmissions T0(Z) and T1(Z) arise, for all samples, in proximity to the beam waist where the pulse energy density is high. Note that a reference pristine (free from Fe2+ doping) ZnSe sample was also under test but no changes in Z-scans T0(Z) and T1(Z)/T0(Z) were found in this case, which ensures an exclusive role of Fe2+ centers in the optical nonlinearities induced in ZnSe:Fe2+.

![]()

Figure 2. Small-signal transmission spectra of ZnSe:Fe2+ with low (sample 464, black curve), intermediate (sample 422, red curve), and high (sample 474, blue curve) Fe2+-centers’ concentrations. For each sample, the transmission nearby the resonance (at pump wavelength l0 = 2.94 mm) and non-resonant loss, measured far away from the resonant band (in bracket), are provided. The transmission offset stemming from the Fresnel loss at samples’ faces is shown by grey line.

![]() (a) (d)

(a) (d)![]() (b) (e)

(b) (e)![]() (c) (f)

(c) (f)

Figure 3. Experimental (empty symbols) and modeled (plain curves) open― (a, b, c) and closed―(d, e, f) aperture Z-scans obtained at pulse energy Ep ~0.56 mJ for ZnSe:Fe2+ samples 464 (a, d), 422 (b, e), and 474 (c, f). The whole of the modelled data have been obtained at σ12 = 0.86 × 10−18 cm2, ξ = 0.03, and η = −0.4 and at thicknesses of layers enriched with Fe2+ centers being 2l = 140 (sample 464), 170 (sample 422), and 230 (sample 474) µm.

![]() (a) (b)

(a) (b)![]() (c) (d)

(c) (d)

Figure 4. (a, b): Maximal transmissions T0max (a) and peak-to-valley oscillations T1/T0max?T1/T0max (b), obtained, correspondingly, from open- and closed- aperture Z-scans, for ZnSe:Fe2+ samples 464, 422, and 474. The experimental data are shown by empty symbols while the modeling results―by plain fitting curves. (c, d): Dependences of Dn-values (c) and the correspondent temperature changes ΔΤ (d) in samples 464, 422, and 474, obtained as the result of modeling. The whole of the theoretical dependences was obtained at σ12 = 0.86 × 10−18 cm2, ξ = 0.04, η = −0.4; thicknesses of the samples’ layers enriched with Fe2+ were taken as: 2l = 120 and 150 µm (sample 464), 150 and 180 µm (sample 422), and 220 and 260 µm (sample 474).

In case of open-aperture Z-scans (see the left panel in Figure 3), rise of T0 at Z→0 is simply the result of Fe2+ centers’ resonant-absorption saturation. However an important detail should be noticed, i.e. that transmittance T0(Z)―even near the focus―is much less than 100%. This indicates the presence of a source of additional nonlinear loss in the material, the effect explained, as it is demonstrated below, by shortening of Fe2+ lifetime via temperature increase under the action of pulsed excitation. Both the phenomena merely contribute in the transmission (absorption) nonlinearity of the samples but the latter contribution dominates at increasing concentration of Fe2+ centers: compare graphs (a), (b), and (c) in Figure 3.

The closed-aperture transmittances T1(Z)/T0(Z) (see the right panel in Figure 3), containing the information about the refractive-index nonlinearity in ZnSe:Fe2+ samples, also demonstrate drastic perturbations at Z→0. Magnitude of the parameter, characterizing the index nonlinearity, a peak-to-valley “oscillation” between the maximal,  , and minimal,

, and minimal,  , transmittances, is much bigger (>1.5) for the sample with the highest Fe2+ concentration (474, see Figure 3(f)) than for the ones with intermediate (422) and the lowest (464) Fe2+ concentration (see Figure 3(e) and Figure 3(d)). The other interesting point is that polarity of Z-scans T1(Z)/T0(Z) in all graphs reveals a positive nonlinear lens “created” in the samples. These facts can be only explained by the effect of considerable thermal lensing (an inhomogeneous increase of temperature) in ZnSe:Fe2+ at 2.94-mm excitation (the coefficient of thermal dispersion of ZnSe:Fe2+ is positive and large [8] ).

, transmittances, is much bigger (>1.5) for the sample with the highest Fe2+ concentration (474, see Figure 3(f)) than for the ones with intermediate (422) and the lowest (464) Fe2+ concentration (see Figure 3(e) and Figure 3(d)). The other interesting point is that polarity of Z-scans T1(Z)/T0(Z) in all graphs reveals a positive nonlinear lens “created” in the samples. These facts can be only explained by the effect of considerable thermal lensing (an inhomogeneous increase of temperature) in ZnSe:Fe2+ at 2.94-mm excitation (the coefficient of thermal dispersion of ZnSe:Fe2+ is positive and large [8] ).

Figures 4(a)-4(b) (see symbols) reveal the experimental laws that the maximal open-aperture transmittances  and the oscillations

and the oscillations  in the closed-aperture transmittances obey at varying pulse energy Ep. These data were obtained from the dependences, similar to those presented in Figure 3 when filters (6) with different attenuations were placed i n front of the samples; refer to Figure 1.

in the closed-aperture transmittances obey at varying pulse energy Ep. These data were obtained from the dependences, similar to those presented in Figure 3 when filters (6) with different attenuations were placed i n front of the samples; refer to Figure 1.

These results testify for: 1) that resonant-absorption bleaching (i.e. an increase of  with increasing Ep) is incomplete in all samples (

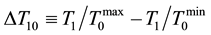

with increasing Ep) is incomplete in all samples ( ), thus indicating the presence of extra loss induced by pulsed excitation (see Figure 4(a)) and 2) that the difference ΔT10 (see Figure 4(b)), the quantity related to Dn-value, demonstrates a virtually non-saturating behavior with increasing Ep, thus indicating the dominant nonlinearity involved being thermal lensing rather than GSA saturation. The results of modeling, presented in the following section (see “plain” curves fitting the experimental dependences in Figure 3 and Figure 4) confirm these ideas.

), thus indicating the presence of extra loss induced by pulsed excitation (see Figure 4(a)) and 2) that the difference ΔT10 (see Figure 4(b)), the quantity related to Dn-value, demonstrates a virtually non-saturating behavior with increasing Ep, thus indicating the dominant nonlinearity involved being thermal lensing rather than GSA saturation. The results of modeling, presented in the following section (see “plain” curves fitting the experimental dependences in Figure 3 and Figure 4) confirm these ideas.

4. Modeling

Propagation of a resonant pulse through ZnSe:Fe2+. Propagation of a ~3-µm pulse through a ZnSe:Fe2+ sample can be modeled by employing the generalized Avizonis-Grotbeck equations [22] [26] -[28] that describe the interaction of light with a medium with saturable (resonant) absorption. However this model requires certain modifications in order to address: 1) the effect of heating of a ZnSe:Fe2+ sample by a pulse since an increase of temperature during excitation should ought to shorten Fe2+ lifetime (as the result, Fe2+ lifetime cannot be fixed at modeling but rather should be a parameter, dependent on pulse energy, accumulated and dissipated in the sample, and therefore on temperature’s growth; 2) the effect of experiencing by a pulse of “extra” loss in ZnSe:Fe2+, an “alter-ego” for incomplete resonant-absorption bleaching of ZnSe:Fe2+ (which stems from the mentioned pulse-induced Fe2+ lifetime reduction); 3) the thermal-lens effect, thereby contributing in overall refractive-in- dex nonlinearity.

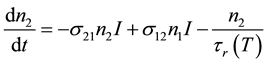

Basic equations: To describe propagation of a pulse at a wavelength resonant to ZnSe:Fe2+ transition 5E→5T2 at arbitrary ratio of the pulse duration to the Fe2+ centers upper level’s relaxation time, we employed the following equations:

(1a)

(1a)

(1b)

(1b)

We consider here a two-level scheme for Fe2+ centers with lower 1 (5E) and upper 2 (5T2) levels, in accordance to the model of ZnSe:Fe2+ energy states; see e.g. Refs. [2] [5] . In this system of equations, n1 and n2 are the population densities of levels 1 and 2, respectively; τr(Τ) is the lifetime of the upper level, which depends on ZnSe:Fe2+ temperature Τ (see below); σ12 and σ21 are the cross-sections of absorption from level 1 to level 2 and stimulated emission from level 2 to level 1, respectively, for a given wavelength λ0 within the Fe2+-centers’ GSA-contour (considered to be homogeneously-broaden); I is the pulse intensity in photons/(cm2∙s); and z is the coordinate running through ZnSe:Fe2+ (it should be not confused with Z-coordinate of a sample positioned as the whole with respect to the beam waist). In system (1a, 1b), the first equation describes the variation in populations of levels 1 and 2 with time and the second one―the variation in pulse intensity upon propagation in the sample. It is implicitly implied that , i.e. that the sum of Fe2+ centers’ populations of levels 1 and 2 is equal to overall concentration of Fe2+ centers n0, which holds at the absence of photo-induced processes (probably leading to variations in valence).

, i.e. that the sum of Fe2+ centers’ populations of levels 1 and 2 is equal to overall concentration of Fe2+ centers n0, which holds at the absence of photo-induced processes (probably leading to variations in valence).

Following the approach [27] , the equation for phase difference Δφsat, experienced by phase φ of the pulse travelling in the sample (which is complementary to the resonant-absorption saturation process addressed by Equation (1) via Kramers-Kronig relations), can be written as:

![]() (2)

(2)

where α0 is the small-signal absorption (GSA) of ZnSe:Fe2+ and δ and η are the coefficients that concern to the relations between the real ![]() and imaginary

and imaginary ![]() parts of ZnSe:Fe2+ susceptibilities in the ground (1) and excited (2) states at λ0. Parameters δ and η are defined as follows:

parts of ZnSe:Fe2+ susceptibilities in the ground (1) and excited (2) states at λ0. Parameters δ and η are defined as follows:

![]() (3a)

(3a)

![]() (3b)

(3b)

and can be found similarly to [27] [28] as Fe2+ absorption and fluorescence spectra are well-known for ZnSe:Fe2+; see e.g. Refs. [1] -[3] [5] [8] [11] [18] [20] [21] . Equations (1)-(2) hold at rather weak assumptions that pulse duration τP is significantly bigger than passing time through the sample and that excited-state absorption (ESA) from state 2 to the above lying states is null.

For the case of a rectangular pulse with duration τP, system of Equations (1)-(2) is reduced to the equation that addresses variation in the pulse energy density ![]() (in photons):

(in photons):

![]() (4)

(4)

and to the equation for ε-dependent phase difference Δφsat:

![]() (5)

(5)

where ![]() and

and ![]() and function S(ε) and ratio of Fe2+ lifetime to pulse duration, ξ(Τ), are written as

and function S(ε) and ratio of Fe2+ lifetime to pulse duration, ξ(Τ), are written as ![]() and

and![]() , respectively. Note that at

, respectively. Note that at ![]() and

and![]() , Eq. (2) transforms to the “standard” Avizonis-Grotbeck equation [26] :

, Eq. (2) transforms to the “standard” Avizonis-Grotbeck equation [26] :

![]() (6a)

(6a)

and to the well-known equation (for intensities):

![]() (6b)

(6b)

where ![]() is the saturating intensity.

is the saturating intensity.

System of Equations (4)-(5) can be used for modeling of a pulse’s propagation through a medium with a single resonance (for an arbitrary ξ(Τ)-value). Specifically, Equation (4) addresses the interaction of pulsed radiation with the medium (and allows one to calculate the nonlinear change in transmission T0(ε)), whilst Equation (5) addresses the phase change (and allows one to determine the nonlinear change in refractive index, Δnsat(ε)).

Temperature impact: Furthermore, attention should be paid to an important issue (regarding ZnSe:Fe2+), the mentioned strong dependence of lifetime of excited Fe2+ centers upon temperature. Apparently, the higher SSA α0 of ZnSe:Fe2+ and the bigger pulse energy EP, the higher an increase of temperature ΔΤ ~ α0EP in the crystal (at neglecting thermal diffusion). As simple estimates show, heating of ZnSe:Fe2+ samples by 2.94-µm pulses can be, in our experiments, of the order of hundreds degrees. Thus, statements (i) and (ii) made above ought to be addressed by means of incorporating the dependence τr(Τ) into the model.

There are evidences to consider shortening of Fe2+ centers lifetime, or “fluorescence temperature quenching”, to originate from strong electron-phonon coupling [3] [5] [21] . This phenomenon can be addressed by the following law:

![]() (7)

(7)

where τrad is the radiative lifetime of Fe2+ centers, W0 is the parameter that stands for non-radiative relaxation (on ZnSe phonons), ΔEa is the activation energy, and kB is Boltzmann constant. The best fit of the known data for τr(Τ) [1] -[3] [5] [21] [29] (see asterisks in Figure 5) is obtained at the parameters’ values: ΔEa = 1750 cm−1, 1/W0 = 0.1 ns, and τrad = 350 ns (at room temperature); see the plain curve in the figure.

Since both Equations (4)-(5) contain the terms dependent upon τr(Τ) (in fact, upon![]() ), an account of the temperature quenching effect in ZnSe:Fe2+ (7) becomes a necessary modeling’s chain. Furthermore, heating of ZnSe:Fe2+ by radiation, resonant to the Fe2+ GSA band, should also contribute in its refractive index nonlinearity. If a ~3-µm pulse propagates through ZnSe:Fe2+, not only the “resonant” contribution in refractive index Δnsat(ε) (associated with perturbations of Fe2+ energy levels―see Equation (4) (5)) arises, but also the “thermal” one Δnth(ε) (stemmed from inhomogeneous heating of the sample). Assuming that for a ~300-ns pulse (our case) thermal diffusion in ZnSe:Fe2+ is negligible, the equation addressing the thermal effect can be written as:

), an account of the temperature quenching effect in ZnSe:Fe2+ (7) becomes a necessary modeling’s chain. Furthermore, heating of ZnSe:Fe2+ by radiation, resonant to the Fe2+ GSA band, should also contribute in its refractive index nonlinearity. If a ~3-µm pulse propagates through ZnSe:Fe2+, not only the “resonant” contribution in refractive index Δnsat(ε) (associated with perturbations of Fe2+ energy levels―see Equation (4) (5)) arises, but also the “thermal” one Δnth(ε) (stemmed from inhomogeneous heating of the sample). Assuming that for a ~300-ns pulse (our case) thermal diffusion in ZnSe:Fe2+ is negligible, the equation addressing the thermal effect can be written as:

![]()

Figure 5. Temperature dependence of Fe2+ centers’ lifetime τr. The asterisks of different colors correspond to the experimental results [1] -[3] [5] [21] [29] and the plain curve (labeled “theory”) is the fit made using Formula (7).

![]() (8)

(8)

where n, ![]() , ρ, and C are the refractive index, thermal dispersion, density, and specific heat of ZnSe:Fe2+, respectively, and

, ρ, and C are the refractive index, thermal dispersion, density, and specific heat of ZnSe:Fe2+, respectively, and![]() . By writing Formula (8), we implicitly assume that the pulse energy is entirely dissipated on ZnSe phonons, given that Stokes loss is ≈100% because the excitation part, leaving a ZnSe:Fe2+ sample in the form of Fe2+ fluorescence, is tiny (<1% [8] ). Note that Equation (8) was obtained at the same assumption of a square-shape intensity distribution inside the sample, made when deriving Equations (4)-(5). The other assumption, about negligible thermal diffusion, is proven by insignificant temperature re-distribution in ZnSe:Fe2+ during the pulse action, given by very low thermal diffusivity of ZnSe (

. By writing Formula (8), we implicitly assume that the pulse energy is entirely dissipated on ZnSe phonons, given that Stokes loss is ≈100% because the excitation part, leaving a ZnSe:Fe2+ sample in the form of Fe2+ fluorescence, is tiny (<1% [8] ). Note that Equation (8) was obtained at the same assumption of a square-shape intensity distribution inside the sample, made when deriving Equations (4)-(5). The other assumption, about negligible thermal diffusion, is proven by insignificant temperature re-distribution in ZnSe:Fe2+ during the pulse action, given by very low thermal diffusivity of ZnSe (![]() , where ρ = 5.26 g・cm?3, C = 0.34 J・g?1・K?1, and Λ = 0.19 W・cm?1・K?1 are density, specific heat, and thermal conductivity, respectively). An estimate for the heat’s diffusion length at tP ~300 ns (our case) is ~2 µm, which is much less than the spatial area where heat is generated, in turn estimated by the Z-scan beam radius w(Z) at the sample’s location (even at the focus it is measured by w0 =75 mm).

, where ρ = 5.26 g・cm?3, C = 0.34 J・g?1・K?1, and Λ = 0.19 W・cm?1・K?1 are density, specific heat, and thermal conductivity, respectively). An estimate for the heat’s diffusion length at tP ~300 ns (our case) is ~2 µm, which is much less than the spatial area where heat is generated, in turn estimated by the Z-scan beam radius w(Z) at the sample’s location (even at the focus it is measured by w0 =75 mm).

The overall phase change, experienced by a pulse, passing through ZnSe:Fe2+, is the sum of the changes, “generated” by the GSA saturation and thermal effects (see Equation (5) and Equation (8)):

![]() (9)

(9)

Z-scan formalism: At making numerical calculations, we assumed that the Z-scan beam is spatially Gaussian, i.e. that the following conditions at the sample’s entrance hold:

![]() (10)

(10)

where r is the radius of the Gaussian envelope, w(Z) and ![]() are, respectively, the spot-size and radius of the beam curvature, Z is the sample’s position with respect to the beam waist [Z0 = 0,

are, respectively, the spot-size and radius of the beam curvature, Z is the sample’s position with respect to the beam waist [Z0 = 0, ![]() and w0 º w (Z0 = 0)], and

and w0 º w (Z0 = 0)], and ![]() is the confocal parameter. The calculations were performed for each Z, designating the sample’s position as the whole with respect to the focus. As the result of calculating Equations (4) (5) (8), the output pulse energy and phase (eout (z = L) and jout (z = L)) were obtained and, consequently, the open- and closed-aperture transmissions:

is the confocal parameter. The calculations were performed for each Z, designating the sample’s position as the whole with respect to the focus. As the result of calculating Equations (4) (5) (8), the output pulse energy and phase (eout (z = L) and jout (z = L)) were obtained and, consequently, the open- and closed-aperture transmissions:

![]() (11)

(11)

![]() (12)

(12)

where Kirchhoff integral is taken over a pinhole transmitting a small part of pulse energy ![]() , with d being the distance between the pinhole and focal point

, with d being the distance between the pinhole and focal point ![]() . The total phase difference and change in refractive index of ZnSe:Fe2+ were found as:

. The total phase difference and change in refractive index of ZnSe:Fe2+ were found as:

![]() (13)

(13)

![]() (14)

(14)

where Leff is the effective thickness [30] of the sample.

Parameters’ values employed at modeling: Thickness of two opposite layers enriched with Fe2+, L = 2l (l is the thickness of a single layer), was estimated for each sample using the method [25] . It was found that L is measured from ~150 µm (sample 464) to ~250 µm (sample 474), depending on the doping temperature, Fe2+ diffusion time, and polishing conditions. Therefore L was varied in the modeling around these values (see e.g. Figure 4(a) and Figure 4(b)). Accordingly, the average Fe2+ concentrations n0, SSA-values α0, and passive losses γ were determined; see Table 1. The saturation energy density was fixed in calculations (Es =0.08 J/cm2) as defined by the value of the GSA cross-section ![]() (at λ0 = 2.94 µm), while the stimulated-emission cross-section was zeroed (σ12 = 0). The values of parameters δ and η, characterizing the relations between the real and imaginary susceptibilities of ZnSe:Fe2+, were found from the absorption and fluorescence spectra of Fe2+ centers [1] -[3] [5] [8] [11] [18] [20] [21] in analogy to [27] [28] . The most reliable values of these parameters were found to be δ = 0.03 and η = −0.4 (at λ0 = 2.94 µm). Pulse duration at the samples’ incidence was fixed: τP =290 ns. To address the thermal effect in ZnSe:Fe2+, the following quantities were taken: n = 2.43 and

(at λ0 = 2.94 µm), while the stimulated-emission cross-section was zeroed (σ12 = 0). The values of parameters δ and η, characterizing the relations between the real and imaginary susceptibilities of ZnSe:Fe2+, were found from the absorption and fluorescence spectra of Fe2+ centers [1] -[3] [5] [8] [11] [18] [20] [21] in analogy to [27] [28] . The most reliable values of these parameters were found to be δ = 0.03 and η = −0.4 (at λ0 = 2.94 µm). Pulse duration at the samples’ incidence was fixed: τP =290 ns. To address the thermal effect in ZnSe:Fe2+, the following quantities were taken: n = 2.43 and ![]() [8] . The temperature dependence of Fe2+ lifetime τr was accounted for by means of Formula (7).

[8] . The temperature dependence of Fe2+ lifetime τr was accounted for by means of Formula (7).

5. Discussion

The results of modeling (see plain curves in Figure 3 and Figure 4) are seen to fit well the whole of the experimental data (see symbols in the figures). Importantly, this agreement has been reached for all samples 464, 422, and 474 without varying neither the GSA cross-section σ12, nor the parameters δ and η.

Transmission (absorption) nonlinearity: First, the strongly limited absorption “bleaching” (i.e. the strongly reduced transmission T0) at high pulse energies (see Figure 3(a)-Figure 3(c) and Figure 4(a)) and almost unsaturated magnitude of T1/T0-oscillation, proportional to Δn (see Figure 3(d)-Figure 3(f) and Figure 4(b)), should be noticed. This testifies for the reason explaining these features being “pulse-induced loss”, which can be solely related to a strong increase of temperature of ZnSe:Fe2+ samples under the pulse action (through the temperature-induced Fe2+ fluorescence quenching phenomenon; refer to Figure 5). Furthermore, since an account of the thermal effect is one of the key points in the model, a dependence of temperature change ΔΤ in ZnSe:Fe2+ upon pulse energy EP is easily obtainable. Such dependences for samples 464, 422, and 474 are demonstrated in Figure 4(d). They, expectedly almost linear on pulse energy for either sample, reveal rise of temperature up to hundreds degrees over room temperature. This allows understanding of the crucial role of Fe2+ lifetime reduction at increasing Τ; refer to (7).

Figure 6 demonstrates an illustration of what happens with the absorptive properties of ZnSe:Fe2+ in terms of optical density OD = ?ln(T0) and pulse-induced loss, both normalized on the values of initial optical density OD0 = α0L (see Table 1), vs. pulse energy EP. The OD-values in Figure 6 were obtained after re-calculating the data

*Defined with accuracy given by the estimates for the samples’ thicknesses.

![]()

Figure 6. Dependences of normalized optical densities (curves 1, 2, and 3) and normalized excessive losses (curves 1', 2', and 3') upon pulse energy for samples 464 (curves 1 and 1'), 422 (curves 2 and 2'), and 474 (curves 3 and 3'). Crossed points are the experimental data (see Figure 4(a) and Table 1) and dashed lines are the fits (plain curves are the modeling results).

presented in Figure 4(a), whereas the values of pulse-induced loss (obtained from modeling made with and without an account of Fe2+ lifetime reduction). [Note that all dependences shown in Figure 6 were obtained for ZnSe:Fe2+ samples placed at the probe beam’s focus, Z0 = 0.]

It is seen that the normalized optical densities of the samples (see curves 1, 2, and 3), though decreasing at increasing pulse energy, do not approach zero, being instead limited by ~50%. Furthermore, the higher Fe2+ concentration in ZnSe:Fe2+, the steeper is a decrease of OD vs. EP. In turn, the normalized excessive losses in the samples (see curves 1', 2', and 3') largely increase at increasing pulse energy; moreover, the higher Fe2+ concentration, the higher is the loss magnitude (say, at EP ~0.56 mJ the pulse-induced losses in samples 464 and 474 are measured by ~5% and ~40%, respectively). Presumably, these trends are an appearance of temperature-in- duced Fe2+ fluorescence quenching. To the best of our knowledge, the revealed laws were never reported for ZnSe:Fe2+.

Refractive index nonlinearity: One more point deserving attention is the dependence of refractive-index nonlinearity Δn on pulse energy EP (see Figure 4(c)), which was obtained after modeling the closed-aperture Z-scans, presented in Figure 3(d)-Figure 3(f). When compared with the dependence ΔΤ(EP) (Figure 4(d)), the behavior of Δn vs. EP becomes clear as mostly stemming from a temperature rise. Indeed, the thermal nonlinearity Δnth is seen to dominate in ZnSe:Fe2+ index change. On the other hand, the “resonant” part Δnsat, associated with the GSA saturation (via Kramers-Kronig relations), was found―when it was calculated separately―to saturate with increasing EP. However, magnitude of this contribution is <5 × 10−5, i.e. Δnsat is always much less than Δnth (>10−3 at the highest pulse energy).

The approach limitations: In spite of satisfactory agreement between the experimental data and theory, certain imperfections can be noticed in details: e.g. it is seen that with increasing Fe2+ concentration (in a sequence of samples 464→422→474), the shapes of the modelled Z-scans get deviated from the experimental ones; Figure 3(a)-Figure 3(c). Certain uncertainties can be also noticed in the behavior T0(EP); Figure 4(a).

A possible cause that stands behind the imperfection of the modeling is the assumption about homogeneity of Fe2+ distribution within the doped layers, which is no more than a rough approximation: in reality, Fe2+ concentration profiles in ZnSe:Fe2+ fabricated by the diffusion method (our case) satisfy the errors’ function [25] . Another problem seems to be the lack of account of such effects as “concentration-related Fe2+ fluorescence quenching” [20] [21] [31] and, hypothetically, a photo-induced process at ~3-µm excitation [15] [32] [33] , which would lead to valence variation in ZnSe:Fe2+. One more factor responsible for the mentioned deviations can be depression of the Fe2+ GSA-band at elevated temperatures (at high-energy excitation). This effect results in a fall of the GSA cross-section σ12 near λ0 =3 µm (see e.g. Ref. [29] ). [Notice that an estimate for Fe2+ lifetime in ZnSe at high temperatures (<12 ns at Τ = 220˚C) [33] ), fits well the dependence plotted in Figure 5 (see the red asterisk).]

It should be also emphasized that our model apparently disregards the known fact that at high temperatures (above 200˚C - 250˚C) ZnSe is chemically unstable and oxidizes into ZnO. The model’s prediction concerning an increase of temperature, established in ZnSe:Fe2+ under the pulse action, tells that T can be as high as 300˚C - 350˚C; however, this happens for the highest EP (>0.55 mJ) and only for the sample with the highest Fe2+ content (474) and exactly at the bean focus; refer to Figure 4(d). Probably, the mentioned chemical instability of ZnSe:Fe2+ at largely elevated T led to sporadic optical breakdown, happened near the focus at these conditions (see Section II). The absence or vanishing probability of optical breakdown in the samples with lower Fe2+ contents (422 and 464) is seemingly a demonstration that the highest temperatures induced in them (refer again to Figure 4(d)) never reach the “critical” ones, at which the chemical instabilities and a trend to oxidizing become notable in ZnSe.

Usefulness for future studies: We believe that, given by increasing interest to ZnSe:Fe2+ as to a perspective laser material for the spectral range ~4.5 - 5 µm (see e.g. reviews [34] [35] ), the issues highlighted in this work are worth of attention. In particular, capacity of effective lasing that the use of ZnSe:Fe2+ samples fabricated through the Fe-diffusion method [6] [36] provides (like the ones inspected above), ensures relevance and usefulness of the current study.

6. Conclusion

We reported a study of the energy-dependent nonlinear transmission coefficient and nonlinear change in refractive index of mono-crystalline ZnSe:Fe2+, fabricated by the diffusion method, at pulsed 2.94-mm Z-scanning. The experiments were fulfilled with a set of ZnSe:Fe2+ samples with different Fe2+ concentrations, at variable energy of a probe pulse and fixed pulse duration (290 ns). The following basic trends were found to exist. First, a dominant role of the pulse-induced thermal effect is established in the transmission/refractive-index nonlinearities of ZnSe:Fe2+ while there is little impact of the resonant-absorption saturation. Second, the thermal effect itself is manifested through: 1) Fe2+ lifetime reduction (temperature quenching) and 2) thermal lensing, with both phenomena associated to significant growth of ZnSe:Fe2+ temperature under the pulse action. The large values of refractive-index nonlinearity (of the order of 10−3), partial resonant-absorption bleaching (not exceeding ~50%), and pulse-induced excessive loss (measured by tens of percent of the initial optical density of the samples) at maximal pulse energy (~0.55 mJ) are the main features revealed for this type of ZnSe:Fe2+ crystals.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Russian Fund for Basics Research (Russia) through the Projects 13-02-01073а, 12-02-00641а, 12-02-00465а, and 13-02-12181 ofi-m, by the grant of President of Russian Federation for state support of the leading scientific schools of Russian Federation NSh-451-2014.2.

NOTES

*Corresponding author.