The Rise of Emerging Markets and Its Impact on Global Energy Security ()

1. Introduction

Daniel Yergin [1] , points out that the concept of security of supply, regarding energy, appears in the eve of the First World War. The First Lord of Admiralty, Winston Churchill, made a crucial decision to make the Royal Navy faster than its German opponent. He ordered the Navy to change its fuel from coal to oil. The coal was produced in Wales. Yet oil was produced in Persia (nowadays Iran). As a result of such a decision, securing the oil supply became an element of global security strategy for the Kingdom. Winston Churchill’s answer to this new issue was “diversification”. This concept, diversification of energy supply and sources, remains as one of the pillars of energy policy.

In this sense, the concept of energy security can be described as “the uninterrupted physical availability at a price which is affordable, while respecting environment concerns”1. This rather lax definition, originates in the first oil crisis.

In 1973 some Arab countries, members of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), used energy as en economic weapon, decreeing an oil embargo on the US and other Western countries. This embargo was a response from the Middle East countries to the support given to Israel by the western nations during the Yom Kippur war. As a result of the cited embargo, the price of oil increased from $2.5 per barrel to $11.6 per barrel. This represented a 350% increase in only two years. The impact on the world economy was grueling. World GDP growth was only 2.5% in 1974 and 1.5% in 1975. The average world GDP growth in the previous decade was 5.1%, a substantially higher rate.

The International Energy Agency (IEA [2] ) was created in response to this first oil crisis. In fact, the main aim of the Agency was, and continues to be, to provide collective and coordinated action by developed countries to a potential disruption of the supply of energy that may either be caused intentionally or merely be the result of an accident. Furthermore, members of IEA are obligated to hold a strategic petroleum reserve equivalent to 90 days of net imports2.

It is true that, nowadays, energy security represents much more than just oil. This is why the IEA takes into account other kinds of energies like natural gas or electric power generation and, ultimately, the energy mix.

Forty years after the first oil crisis, security of supply is still a key issue on the international agenda. In 2011 the civil war in Libya, along with its impact on the oil market, forced the IEA to carry out collective action to smoothen the impact of this war on the global economy [3] . Thus, some of the countries of the Agency released 60 million of barrels of oil (or petroleum products) into the market, preventing an additional increase in oil prices3. Moreover, in early 2012 the eyes of the world looked carefully on the events on the Strait of Hormuz, the main chokepoint of the energy system. Western countries, specifically the European Union, have declared an oil embargo on Iran while Iran increases its military presence in the Strait of Hormuz. In accordance with the IEA, around 17 million barrels of oil and 2 million petroleum products cross the Strait daily, i.e., 20% of world oil production.

The civil war in Libya, Arab social unrest, the Arab Spring and the increasing problems of western countries with Iran on its nuclear program, have made energy security become a hot-button issue of the mass media. However, let us recall here the ideas of James Schlesinger, America’s first Secretary of Energy (1977-1979), on security. According to Schlesinger, there are only two models: complacency and panic, and we have to escape from them both.

In the same sense, a recent document titled Spanish Security Strategy [4] highlights that “both the guarantee of fossil fuel supply and its price could be exposed to significant tensions in this decade. Contributing factors include the high demand from emerging economies and the concentration of oil and gas in politically unstable areas”.

It seems that the concept of energy security and security of supply is, to say the least, as relevant as it was in the past. However, the economic and political environment that shapes the design of energy security has greatly changed since the first oil crisis. Furthermore, many experts point out that the new political and economic equilibriums make this concept much more relevant today than it was in the past (Ed Morse, 2011)4. This is precisely the main idea of this paper.

2. Background

2.1. A Theoretical Approach to Security of Supply

This concept, security of supply, is polyhedral. Although energy security is a very relevant concept, measuring it objectively is very complicated. To illustrate this point we want to mention the Institute for 21st Century Energy elaborates an index of energy security [5] , a quantitative approach to the problem. This index attempts to measure energy security in the US or, at least, to measure whether energy security improves or worsens over time. This index takes into account several domestic and international variables such as reserves, access to these reserves, carbon emissions, political issues, price volatility, etc.

Yet this paper studies only one of the aspects of energy security: potential international cooperation in the hypothetical case of a global emergency. It is noteworthy to point out this aspect is not addressed in the US Energy Security Risk, stressing the difficulties to assess accurately this concept.

Clearly, in the case of a global energy problem, coordinated action by the international community can reduce or smooth the severity of the problem. However, in order for international cooperation to be effective, some conditions must be considered. Most importantly, there must be ongoing fluent communication among the different participants. It is only possible to cooperate and coordinate actions at different moments when there is a constant and regular flow of communication and dialogue among members. In our context, this communication takes place. In particular, the OECD [6] members through the International Energy Agency have an open communication with some key emerging consumers, like China and India, and also with key producing countries, like the OPEC.

But this is not enough. They must also share similar objectives. This is much more complex. That is to say that, for example, India and China may share the same strategic objectives as the OECD countries, i.e., guaranteeing the “sufficient” supply of energy in case of a crisis. However, we must recall here that the political and international aims of OECD and emerging countries are not necessarily common. On the contrary, they may in fact be very divergent. Moreover, the strategic objectives of consuming and producing countries are, generally speaking, different. Consumers want cheap energy, while producers prefer expensive energy.

The world has changed dramatically over the last 20 years. It is fair enough to say that as things stand right now, it is practically impossible to lay out an efficient security policy without counting in emerging economies. This paper precisely explores the new world of energy, puts emerging economies into the picture and gives these emerging economies the same weight, in terms of relevance, as it gives to developed countries.

2.2. The New Energy Equilibrium: The Rise of the Emerging Economies

The geopolitical chessboard has change dramatically in the last decades and the energy map is not an exception to this movement. The world and the new economic equilibriums of 2012 are quite different to those 30 years ago, when the oil crisis took place. The main reasons behind this change are:

a) Stronger demographic growth in emerging countries The strong demographic growth in emerging economies is a well-known phenomenon. In the developed countries there are around 200 million more people than there were 30 years ago. Per contra, the population of the rest of the world has increased by 2150 million people for the same period, i.e., a growth rate 10 times bigger than that of the developed countries [7] [8] .

b) Emerging economies represent a larger share of world GDP Logically, this change in demographic equilibrium has led to a change in the relative size of the economies. Developed countries amounted to 2/3 of the world GDP in 1980. Yet today they only amount to 1/2 of the world GDP (see Table 1).

This change in the relative size among emerging and advanced economies has been accompanied by a change in energy consumption.

In this sense, emerging economies have fed their demographic and economic growth with energy. Oil consumption has grown 90%, natural gas consumption has grown above 200% and coal consumption has also grown 200%. Contrarily, energy consumption in advanced economies has been moderate (see Table 2)5.

c) Stronger economic growth in emerging countries.

From a geopolitical point of view, the entrance of emerging economies into the world arena characterizes the last decade. These countries, initially only eternal promises on the geopolitical stage, have now become the main characters. We could highlight, for example, that economic experts expect China, India, Brazil, Russia, Turkey and South Africa to maintain an economic growth rate above 4% per year vs. the lean 2.5% growth rate expected from OECD countries. They also expect the aggregate GDP of these countries to surpass the European Union GDP by 2016. What is more, given their demographic power, these countries will represent 45% of the

Table 1 . GDP in power purchasing parity.

Source: International Monetary Fund.

Source: British Petroleum 2012 [9] .

total world population (around 3100 million people) in 2016. Both strong economic growth and demographic power paint a future energy scenario defined by a strong increase in demand, accompanied by the logical tensions in international markets.

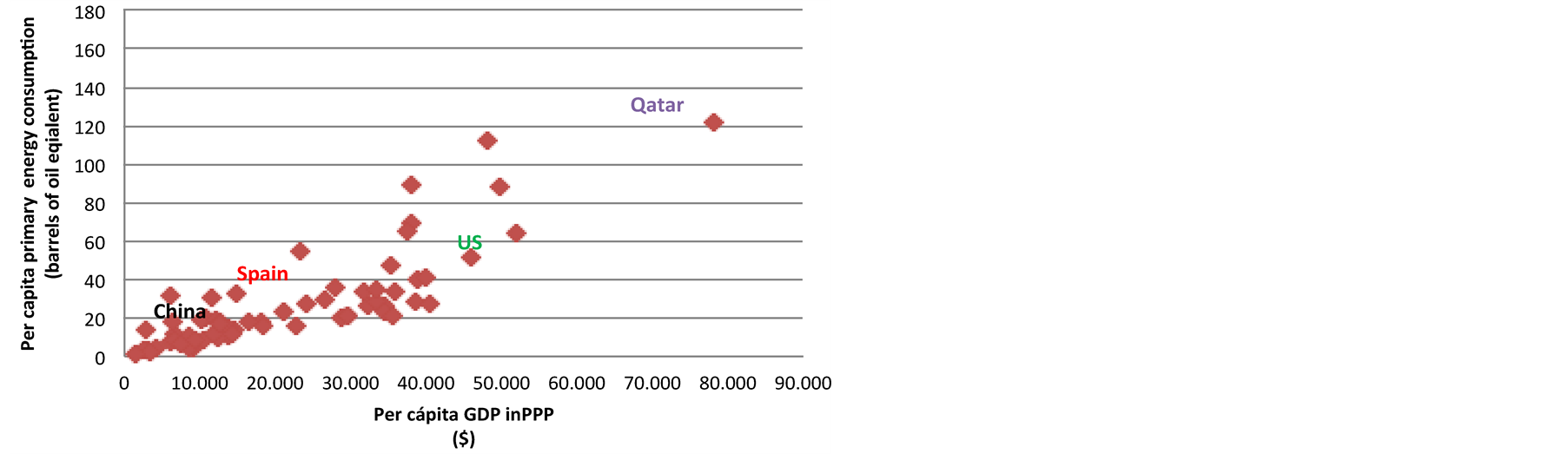

d) Higher per capita growth in emerging countries These countries not only have a stronger demographic growth, but also a higher economic growth in terms of per capita. Per capita GDP in advanced economies has grown 3.2% over the last decade vs. 9.5% in “developing Asia”, 4.1% in “Latin America” or 4.5% in “the Middle East and North Africa”6. Obviously, citizens from emerging economies aspire to the same living conditions that citizens from advanced countries already have. From an energy perspective, it is quite important to internalize the impact of per capita economic growth on energy consumption: the higher the per capita GDP is, the higher the per capita energy consumption is, as shown in Chart 1. To illustrate this point: if the world had consumed the same energy per capita as Spain in 2010, the global energy demand would be approximately 50% higher. This demand would be impossible to satisfy, given the current path of energy production.

e) Emerging economies have more geopolitical influence Most economists foresee that emerging economies will continue gaining political and economic influence over the following years. This scenario, dominated by emerging countries, leads to a new scenario with direct implications on energy security.

These trends in economic performance, demographic evolution and per capita GDP growth have an evident impact on energy markets. The US, China, Japan, India and Germany were the top 5 oil net importers7 in 2010, as can be observed in Chart 2. It is quite evident (at least this is what we think) that advanced countries cannot implement an effective policy regarding the security of oil supply without counting on the emerging economies. This picture is quite different from that of 1974, when the International Energy Agency was born.

Thirty years ago advanced economies were the main oil importers and also the main petroleum consuming countries. Energy security and security of supply was a concept associated to rich and developed countries. However, the world has changed and, nowadays, energy security is not only relevant for OECD countries, but also for emerging economies. Even more, these countries are developing their own strategies to deal with the problem of energy supply as, for example, Trevor House explains in his article published by the Financial Times8. In the same sense, this newspaper has also recently published that the Chinese Prime Minister has visited some Middle East countries to secure supplies for China, given the tension between Iran and western countries9.

2.3. The Energy-Supply Side: A Factor of Geopolitical Risk

In the previous section we have analyzed the relevance of emerging economies from the point of view of energy

Chart 1. Per capita energy consumption and per capita GDP. Source: Blazquez & Martín-Moreno.

Chart 2.Net oil importers in 2010. Source: Blázquez & Martín-Moreno, using BP database 2010.

demand and consumption, both in the short term and medium term. And we have pointed out that the present scenario is very different from that of 30 years ago. Emerging countries now have an emblematic role in the energy market. Contrary to this, the general panorama of oil producing countries is not so different to what it was 30 years ago. If we compare the ranking of the 15 top oil producers in 1980 and in 2011, there are only small differences (see Table 3). Nowadays, Saudi Arabia, Russia (the former Soviet Union, in 1980), and the United States are the world’s main producing countries. This was the same 30 years ago.

One of the most interesting characteristics of the oil market is that production is very concentrated, allowing the possibility to create cartels very easily. In 1980 the 15 top producer countries supplied 88% of total world oil output. In 2011 the 15 top producers supplied “only” 77% of total output. It is true that there are new countries on the list and oil production is less concentrated, but this fact has to do, in part, with the dismemberment of the former Soviet Union. In any case, the degree of geographical concentration of oil production is quite significant, so we can affirm that the market is controlled by a small group of countries. It is not necessary to emphasize the relevance of this concentration from the viewpoint of energy security. Oil remains the most relevant source of primary energy today, amounting to 1/3 of the total energy consumption [10] .

Nowadays the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries, the OPEC, is the most relevant player of the oil market, as was the case 30 years ago during the first oil crisis. In 1973, the OPEC produced 30 million barrels per day (51% of world’s output) and the developed economies produced 15 million (25% of the world’s output). In 2011 the OPEC supplied 36 million barrels per day (43% of total output), while OECD countries produced 19 million (22% of the total). Despite the fact that OPEC’s output is less significant, its capacity to influence the market is as relevant as it has been for the past 40 years. The political and economic predominance of the OPEC in the oil panorama remains intact.

The second source, in terms of demand of energy, is coal. This commodity is living a new period of splendor by the hand of emerging economies. These countries have multiplied their coal consumption by 3 since 1980.

The great difference between coal and oil is the geographic diversification of coal. This source of energy is spread all over the world, given that this raw material has a clear advantage from the point of view of security of supply. In fact, the ample geographical distribution of coal is an element that improves global energy security. In this sense, whilst being the first producer China is at the same time the first consumer. Chinese power generation

Source: British Petroleum 2012 [9] .

rests heavily on coal. Chinese consumption of coal is the equivalent to the aggregate demand of the United States, India, Japan, Russia, South Africa, Germany, South Korea, Poland, Australia, Indonesia, Ukraine, Kazakhstan, Turkey, United Kingdom, Canada, Thailand, Italy, Vietnam, Brazil, Greece, Mexico, Spain and the Netherlands. Quite impressive! Despite its immense demand for coal, China does not need to import this coal from abroad. Table 4 shows that 5 countries consume 80% of global production and all of them, except Japan, are practically self-sufficient.

World consumption of coal has practically multiplied by 2, pushed by emerging countries since 1980. China and India add up to almost 60% of total demand and both countries have multiplied their demand for coal by 2 in the last decade. In this sense, it is urgent to break off from the idea that coal is a type of energy of the past. Currently, coal is the most vibrant source of energy. According to IEA estimates, the additional demand for coal in the last 10 years is equal to the sum of all the additional demands for oil, nuclear energy, renewable energy and natural gas for the same period. Since 2000, the effervescent growth of emerging economies has increased the share of coal in the energy mix above the levels in the 80’s (see Chart 3). In this context, a recent article by The Economist—“The Future is Black”—explains that coal is India’s bet to feed its demand for electricity10.

Obviously, the negative flip-side of the new bet on coal is the increase in greenhouse emissions. There are many studies that point out that these additional emissions could generate a significant change in global weather and affect ecosystems along with the world economy. There is no doubt that climate change is one of the main challenges of the international community, as shown by both the Kyoto Protocol and, more recently, the Durban Climate Change Conference (2011). In this sense, the European Union is leading the movement against climate change; it commits to a 20% reduction in greenhouse emissions by the year 2020.

Chart 3.Share of coal in world’s energy mix. Source: Blazquez & Martin-Moreno.

Table 4. Consumption and production of Coal, 2011.

Source: British Petroleum 2012 [9] .

Renewable energies are not only a way to fight greenhouse emissions. They are also a good mechanism to strengthen energy security. We are used to thinking of these new technologies as way to be greener but, alternatively, these energies provide countries with an additional national source of energy. It is true that renewable energies are more expensive than traditional hydrocarbon fuels. Yet if we want to tackle a fair economic analysis of renewals, we must include all the externalities. Even though the impact of oil, coal and natural gas on greenhouse gases and on climate change is clearly a negative externality, renewable energy does additionally reinforce the energy security of a country. This concept should be included in economic studies.

It is important to point out that climate change has implications from the point of view of security. In this context, the Spanish Ministry of Defense published, in 2011, a book that explores the relationship among energy, climate change and security [11] .

The last energy resource that we are going to study in this paper is natural gas. Although some years ago this commodity was a source of energy traded regionally, (not globally), it is quickly becoming global, as is the oil market. Natural gas amounts to 1/4 of the total world’s energy consumption and it is the fastest-growing source of energy.

From the point of view of energy security, natural gas is between coal and oil. Natural gas production is geographically more diversified than oil, but less than coal. The US, Russia, Iran, China and Japan are the main consumers11. Russia is, in addition, the largest exporter, and Iran, a smaller one. China and the US are almost self-sufficient. Only Japan rests totally on imports of natural gas.

The largest importers of natural gas are, in general terms, the European countries. In fact, Germany, Italy, and France, in addition to the US and Japan, were the main net importers of natural gas in absolute terms in 2010. Given the absence of conventional gas in Western Europe and, also, given the strong consumption of this kind of energy, natural gas plays a key role regarding energy security in Europe. In this sense, European countries and the US share the same vision of security regarding oil, but do not see eye-to-eye in the case of natural gas.

However, the panorama of natural gas could change dramatically over the next years and may favor a less risky world regarding security of supply. The energy world is immersed in a technological revolution concerning unconventional gas, shale gas being the most emblematic one. This revolution in the same way as, for example, hydraulic fracturing or fracking, is making gas-mining much more efficient. According to some studies, these new technologies could double natural gas reserves from 60 years of current consumption to 120 years. For instance, the cost of gas production in the US, the country where these new technologies are being developed and put in place more rapidly, has been reduced by 30% and there are estimates that suggest that gas reserves could total up to more than 200 years of current consumption.

In fact, many US companies are investing and increasing their production of natural gas despite the sharp reduction in gas prices. It seems that this revolution will spread all over the world, if environmental doubts and problems are completely solved.

In any case, if the shale gas revolution spreads out, the panorama of energy security will change substantially. In accordance to some estimates, OECD countries could have 25% of the world’s reserves of non-conventional gas, versus a 9% of conventional gas. Shale gas could be a clean alternative to coal and could also be a way to improve energy security.

2.4. Public Oil & Gas Companies from Emerging Economies: The New Seven Sisters

In previous sections we have pointed out that emerging economies have a large share of current production, but they also have most of the conventional reserves of petroleum and natural gas. Both elements, reserves and production, have allowed for the creation of gigantic public companies in those countries. In this sense, Nicholas Vardy, 2007 mentions the new seven sisters. These new sisters are, by their relative importance: Saudi Aramco (Saudi Arabia), Gazprom (Russia), CNPC (China), NIOC (Iran), PDVSA (Venezuela), Petrobras (Brazil) and Petronas (Malaysia). In fact, these companies control 80% of the total world reserves. Oil & gas companies from OECD countries are almost marginal. Only ExxonMobile (USA), Shell (Netherlands) and British Petroleum (UK), among international oil companies, come up among the largest world companies by reserves. Obviously, these giant-sized public companies are the fruit of domestic reserves and a regulatory system that pushes aside foreign companies. As has been mentioned all along in this paper, conventional gas and oil reserves are concentrated geographically in a few countries. See Table5

Table 5. Proven reserves of petroleum and natural gas.

Source: British Petroleum 2012 [9] .

Please note that the control that these kinds of companies have on the reserves generates some uncertainty in the market. Public companies do not operate under strict market criteria, as do private companies. This fact is not necessarily a problem per se. Some of these companies are managed impeccably, following strict criteria to guarantee economic profitability. Some national states use these companies as, so to say, piggybanks (Nicolas Vardy, 2007 [12] )12. In this context, on some occasions the IEA has expressed that these companies could be under-investing, given that they are run with no-market criteria. This under-investment could negatively affect future production. It is important to stress that energy security relies on “sufficient investments” in order to supply the world with energy at “reasonable” prices tomorrow.

It is obvious that, from the perspective of energy security, public companies are an additional element of concern given that their investments and production also depend on political issues.

2.5. World Oil and Gas Trade and Geographical Choke Points

Marzo [13] warns that the increase in oil trade will reinforce the current economic interdependence of the world. But, at the same time, importing countries will be more vulnerable to short-term disruptions in supply. According to Marzo, the geographical diversification of oil will diminish. On the contrary, oil and gas trade will boost and this, in turn, will stress world dependence on few trade routes [13] . In fact, as Marzo points out, oil and gas trade travels through critical choke points; this makes it very assailable. In the same sense, Lehman Brothers (2008) signaled choke points as being a significant concern for security of supply13.

Emerging economies have no direct impact on these choke points, but they do, however, affect them indirectly. They generate additional demand for energy and, then they bring about an increase in oil and gas trade, which does, indeed, affect choke points.

The US Energy Information Administration (US EIA [14] ) also thinks that choke points could be a risk to energy security. A report entitled “World Oil Transit Choke Points” by the US Energy Information Administration says: “World oil chokepoints for maritime transit of oil are a critical part of global energy security. About half of the world’s oil production moves on maritime routes.”

The US Energy Information Administration indicates 6 critical choke points regarding oil trade. In order of relevance, these choke points are: Strait of Hormuz (15.5 million barrels per day), Strait of Malacca (13.6 million barrels per day), Strait of Bab el-Mandeb (3.2 million), the Bosporus (2.9 million), the Suez Canal and the Sumed pipeline (2.9 million) and, finally, Panama Canal (0.8 million). See Chart 4.

We would like to highlight that these choke points represent an on-going increase in risk as oil trade increases.

Chart 4.Oil trade and choke points. Source: US Government Accountability office.

The greater the trade is, the greater the risk becomes.

2.6. Emerging Economies and Strategic Petroleum Reserves

Member countries of the IEA have strategic reserves. These reserves can be used only in emergency situations. They constitute the main mechanism to confront oil supply disruptions. These reserves can be held by the private sector or the public sector and they can be stored in crude oil or petroleum products. Currently, the strategic reserve of the OECD countries adds up to approximately 145 days of net imports.

Strategic reserves are devised to face “HILP” events. HILP means High Impact, Low Probability. These HILP events take place very rarely, but they are very deleterious. Lee and Preston [15] explain that there are three kinds of HILP events. The most popular one is called the Black Swan. It is impossible to anticipate and, then, it is impossible to be prepared to deal with it.

Another one is called “known and prepared for”. The IEA knows that an energy crisis may take place. They take place from time to time, but they occur. The IEA has mobilized the strategic oil reserve on three occasions: during the first Gulf War, after the Katrina Hurricane, and very recently during the civil war in Libya. Apparently, there is a serious disruption in oil supply every 7 - 10 years.

The last kind of HILP event is called “known but unprepared for”. We can find the majority of emerging economies in this situation. Oil supply disruptions, in a global market like ours, has an impact on developed and emerging economies at the same time. Perhaps, 5 or 10 years ago, the OECD strategic petroleum reserve was large enough to stabilize the oil market in the case of a transitory, although severe, crisis. However, given the strong demand of energy by emerging economies, the overall picture, if a crisis occurs, is much more complex. China and India, due to their large demand, are key players in the energy markets. This is why the IEA is permanently in touch with them, but this is not enough. It would be necessary for these countries to build their own strategic oil reserve to tackle the next global oil crisis.

In this context, China is doing its homework and it is building its strategic reserve of oil. Even more, it seems that China is accelerating this process, given the political and military tension between Iran and the Western world, as Leslie Hook has suggested in a Financial Times article (18th January 2012).

3. Key Countries from the Point of View of Energy Security

In the previous sections we have shown that emerging economies are very significant players from the point of view of energy demand and, thus, from an energy security standpoint. The international community cannot develop an energy agenda without an active participation of the emerging economies. On the contrary, from the supply perspective, particularly oil, the situation is similar to what it was in the past. In this section, we select the world key players regarding energy security, analyzing both viewpoints: the demand side and the supply side.

The first relevant point is that the quantities traded in oil markets are much larger than those of natural gas markets. For example, Japanese and German imports of oil double, in terms of energy, those of natural gas. In the case of France, oil imports triple natural gas imports. None of these countries has a significant production of oil or gas. In the same sense, petroleum net imports of the sixth largest countries added up to 1275 million tons in 201014. In the case of natural gas, main importing countries bought an equivalent to 335 million tons of oil. These figures show that the international market of petroleum is 4 times greater than that of natural gas.

Clearly conclusively, in terms of energy security, oil is by far the most vulnerable source of supply.

Chart 5 shows the situation of all the countries, importers or exporters, in respect to oil and gas. In fact that chart shows the net exports of natural gas and oil of each country—defining net exports as production minus consumption.

The chart shows that Russia, Saudi Arabia and the US are quite atypical values. From the point of view of the importers, the US is by far the largest importing country and a very large importer of natural gas in 2010. Nonetheless, the US is reducing its imports of gas very quickly and it will soon become self-sufficient. From the perspective of the exporters, we could consider Russia to be the most strategic country. The reason behind this assessment is that Russia is the largest producer of natural gas and the largest producer of oil (slightly behind Saudi Arabia). In other words, Russia is vital for oil and natural gas markets. Russia has to be committed to world energy security to guarantee well-supplied energy markets.

Saudi Arabia is as relevant as Russia on the petroleum side. Also true is that Saudi Arabia is considered as the central bank of oil because this country has a significant spare capacity15. The International Energy Agency has recently defined Russia as the cornerstone of the world energy system [10] .

Method and Results

A simple way to choose the key countries for world energy security is using the standard deviation of the net exports. In this sense, we calculate the standard deviation of the net exports (domestic production minus consumption) of petroleum and natural gas for all the countries in 2010. In a first step we calculate the net exports of oil and natural gas for all the countries. This allows us to create a ranking of larger importers and exporter. But to become a key country you have to be a really relevant net importer or exporter from a statistical point of view. Then, secondly, we calculate the standard deviation of the whole sample. Once we have the standard deviation, we select as key countries only those countries with higher net exports, in absolute terms, than the standard deviation (see Table 6).

On the one had, we find 6 key countries form the point of view of the demand (importers), 2 of them being emerging economies: China and India. The rest of the countries are members of the IEA. It is clear that if the

Chart 5.Net exports of oil and natural gas. Source: Blazquez & Martin-Moreno.

Table 6. Key countries for energy security (Ranked by its relative importance).

Source: Blazquez & Martin-Moreno, using the BP database 2010.

OECD world, i.e., the IEA wants to carry out an efficient policy on energy security; it needs to coordinate its agenda with India and China. On the other hand, Russia leads the group of key exporting countries, but the other 5 key countries are OPEC members!

Regarding natural gas, Turkey is another emerging economy that is a relevant importer, the other 6 countries being members of IEA [16] -[18] . From the point of view of exporting countries of gas, Russia appears to be again as the most important one. Norway and Canada are members of the OECD. Qatar, Algeria and Indonesia complete the overall picture. The natural gas market is different to oil. In this case, exporters are much more diversified geographically and there is no oligopolistic association like the OPEC.

In light of these results and considering the fact that only the developed economies are members of the International Energy Agency, it is clear to see that the International Energy Agency does not have sufficient capacity to build up a global energy security strategy on its own. Neither does the OPEP, given that main consuming countries and some a few relevant producers are excluded. In order to coordinate the efforts of producers and consumers, Saz and Pierce, 2011 bring out the need for a global governance of energy. In fact, they propose quite an interesting idea: “The International Energy Agency should hasten its outreach to emerging economies, modifying its membership requirements if necessary, to allow important new consumers such as China and India to join this regime”. This idea means that the Agency has to abandon the shelter of the OECD. Perhaps it is time to do so.

4. Concluding Remarks

The World Economic Forum considers that one of the main risks for the world economy in 2012 is the extreme volatility of energy prices [19] . In the same sense, the Government of Spain recently pointed out that price volatility and tensions in energy supply are a risk for national security [4] . The Arab Spring, the civil war in Libya, the political and military tensions among Iran and Israel and the US, and the nuclear crisis of Japan (Fukushima) have strongly affected energy prices in 2011. As a result of these events, energy security has been a primordial issue on the international agenda.

The strong growth of emerging economies is probably the most relevant characteristic of the world economy over the last 10 or 15 years. Nowadays, these economies are key players of the global economy and energy security too. In 1990, consumption of energy by OECD economies was 13 percentage points above consumption by non-OECD countries. Now, non-OECD economies consume more energy than do developed countries (OECD). In accordance to some estimates, energy demand by non-OECD economies will double OECD demand by 2030, while at the same time this group (non-OECD economies) only represents 30% of world energy consumption.

This paper has highlighted that, in order to guarantee the significant impact of OECD policy on markets, it is convenient to at least count on the active collaboration of China and India. This is why the International Energy Agency, energy watchdog of the OECD, holds regular meetings with both countries. Within this context, the Chinese policy to create a strategic petroleum reserve is good news.

The new economic scenario in favor of emerging economies makes a mirror image on the energy business world. The new oil and natural gas titans are now public companies from emerging markets, while private companies from developed world play second fiddle. Future energy supply rests on sufficient investments today and a relevant share of these investments must be carried out by public companies subject to political criteria. This concept, sufficient investments, adds another element of uncertainty and risk to the global scenario.

This paper points out that oil is the most vulnerable source of energy; there are three reasons that support this idea. First, oil is the energy that is most intensely traded internationally. Second, oil reserves are concentrated geographically in few countries. Third, oil trade has to deal with physical choke points like the Strait of Hormuz or of Malacca. Thanks to its ample reserves all around the world, coal and, to a lesser extent, natural gas (in the midst of a technical revolution) are taking the lead of oil. Without doubt, there are some elements that could explain this tendency, but energy security is definitely one of them and, probably the most relevant one.

Finally, this paper suggests that Russia is the world’s cornerstone of energy supply. Additionally, the OPEC remains to be the most relevant player in the oil markets as it has been over the past 40 years.

NOTES

*José-Maria Martín-Moreno thanks the financial support by Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad ECO2011-23959 and by Xunta de Galicia 10PXIB300177PR to elaborate this paper.

1The International Energy Agency defines energy security in its web page at www.iea.org/topic/energysecurity/.

2http://www.iea.org/topics/oil/oilstocks/

3The report by Reuters (June, 2011) explains, in detail, the context in which the decision was taken by the IEA. In that moment, as the reports points out, the oil market thought that the price could reach $150 per barrel.

4Ed Morse, 2011. “Expect More Oil Price Rises in the World of New Geopolitics”, Financial Times, April 6th.

5In 1980 the total consumption of oil and natural gas in industrialized countries amounted to around 65% of world consumption. Yet, their consumption only amounted Arato 50% of the world coal consumption.

6Here we use the glossary and the database of the International Monetary Fund.

7We define net oil imports as the difference between production and consumption of oil.

8Trevor House, 2011. “Oil-Hungry China Needs an Energy Security Rethink”, Financial Times, 17thMarch.

9Financial Times, 2012. “Chinese Prime Minister Seeks to Deepen Gulf Energy Ties”, January 11th.

10The Economist, 2012. “The Future is Black”, January 21st-27th, page 64-66.

11In accordance with the British Petroleum 2010 database.

12Nicholas Vardy (2007).

13Lehman Brothers (2008), “Global Oil Choke Points”, Energy & Power, 18th January.

14Here we define net imports as the difference between consumption and domestic production. A positive figure means that the country is a net exporter. A negative number means that the country is a net importer.

15According to the Oil market report by the IEA (18th January, 2012), Saudi Arabia could increase its production by 2.15 million barrels per day.