Comparative Anatomy of the Vasculature of the Dog (Canis familiaris) and Domestic Cat (Felis catus) Paw Pad ()

1. Introduction

Arctic mammals such as arctic foxes and wolves are well adapted to live in the cold Arctic. They travel on the snow and ice hunting for prey. Henshaw and Underwood showed that these animals maintain their foot temperature just above the tissue freezing (about −1 degrees C) when the foot is immersed in a −35 degrees C bath in a laboratory setting [1]. They suggested that increased blood flow to the foot pad surface is the mechanism. Furthermore, Henshaw suggested that arteriovenous anastomoses (AVAs) have evolved in the foot pad and that AVAs augment the heat delivery and protect tissues from frost bite [2]. Prestrud proposed a probable contribution of a countercurrent vascular heat exchange in the legs to reduce heat loss in the arctic fox [3].

It has been well established that dogs possess footpad particularly consisting of two components: venous and arterial vessels enmeshed with one another [4], which is the functional analogue of the tongue, fins and flukes of whales, dolphins [5] and manatees [6 ], serving to conserve core body temperature. As the foot pad is highly vascularized and relatively uninsulated, representing a surface for heat loss and many breeds of dogs can be traced back to the arctic, in some ways these breeds are going to be better equipped to handle the cold weather as in the arctic animal [4].

As the morphology and function of the footpad are related directly to the habitat for the species, observing the differences of the vascular system of each species might be of concern for the researchers. Further, data on the footpad microvasculature of domestic cats appears to be lacking. The goal of the study was to clarify the microvasculature of the dog and domestic cat and to compare those of both species.

2. Materials and Methods

Four dogs (beagle, adult, male) were anesthetized with an intravenous injection of sodium pentobarbital (25 mg/kg) and bled through the carotid artery to use for exercise of veterinary anatomy at Azabu University. Sixteen legs from the cadavers were collected when the exercise finished two hours later. Three domestic cats (hybrid, adult, male and female) were euthanized by injecting overdose sodium pentobarbital at private veterinary hospitals. Twelve legs from 3 domestic cat cadavers were amputated.

A cannula was inserted into the humeral and/or femoral artery of the amputated limbs and 0.9% physiological saline was injected to wash out the vascular system. In 12 dog limbs and 10 feline limbs, a combination of methylmethacrylate monomer and Mercox (Dainippon Ink & Chemical Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) (ratio in volume = 8:2) with a sprinkling of chromophtal red (Ciba Co. Ltd., Swiss) was subsequently injected. The resin was slowly injected into the arteries with a moderately firm finger pressure applied to the plunger. The infusion was continued until the resin appeared in the contralateral humeral and/or femoral veins. Then the injected legs were placed in a water bath at 40 degrees C for 30 min to allow the resin to harden. If satisfactory filling was obtained, the injected legs were corroded by immersing in 20% NaOH for several days. The cast was carefully washed in distilled water and air-dried. The vascular specimens were mounted on aluminium stubs and coated with gold (IB-3, Eiko Engineering Co. Ltd., Ibaraki, Japan) for observation with a scanning electron microscope (ABT-32, Topcon Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). In another 2 dog limbs and 2 feline limbs, Indian ink in 3% gelatin was injected by the same method as for the resin injection. The injected foot pads were fixed in l0% formalin for a few days, embedded in paraffin wax and sectioned in 100 μm thick slices for the whole mount specimens. In the remaining 2 limbs, the pads were fixed in l0% formalin and 4 μm thick sections were stained with haematoxylin and eosin for histology.

3. Results

3.1. Histology and Whole Mount of the Paw Pad

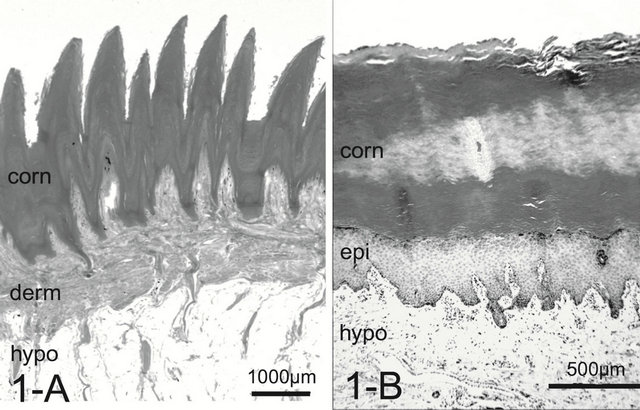

A dog’s foot pad is actually made up of multiple small protuberances called conical papillae (200 - 300 μm high, 200 - 300 μm wide at the base). The surface of the pad is devoid of hairs. The histology was like that of the general integument. The conical papilla is a spike-like structure ending with abundant cornification at the apex of the papilla (Figure 1(A)). Tall dermal papillae projected from the dermis into the stratum basalis of the epidermis. The epithelium was quite thin with 3 - 5 cell layers. The microvascular units in the dermal papilla consisted of several capillaries just underneath the epithelium and a few venules in the core of the papilla (Figure 2(A)). Nerve fibers, encapsulated sensory endings such as Pacinian corpuscles, profuse blood vessels, and lymph vessels were present throughout the connective tissue in the hypodermis. Arteriovenous anastomoses (AVAs) were frequently found, in the form of either a glomerularshaped body or a direct connection. Eccrine sweat glands were usually found. The thick layer of subcutaneous adipose tissue was separated by connective tissue into small individual compartments throughout the hypodermis.

Figure 1. Histology of the foot pad. In dogs, the elongated spike-like conical papillae (protrusion) may retain an insulating layer of air between the pad surface and cold substrate.The thick layer of subcutaneous adipose tissue also provides thermal insulation and cushioning (A). In cats, the pad surface is smooth without conical papillae (B). Abrreviations: corn: stratum corneum, derm: dermis, epi: epidermis, hypo: hypodermis. H & E stain.

Figure 2. Whole mount of the paw pad. Note profuse veins forming a well developed venous plexus in both species (A), (B). The ink injected was washed away in some veins during the procedure of the whole mount (arrow heads).

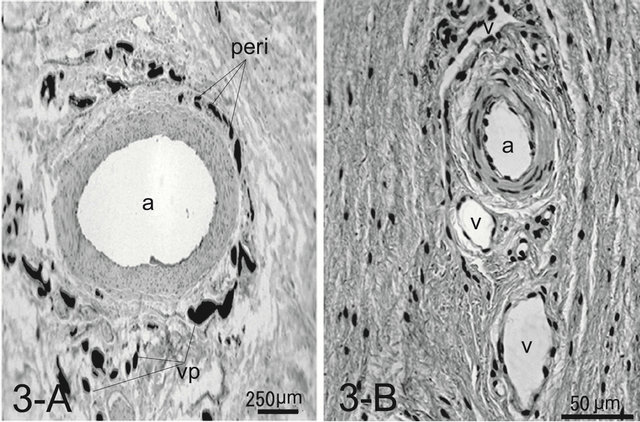

Numerous arteries in the dermal layer accompanied venules in their tunica adventitia, forming a peri-arterial venous plexus (Figure 3(A)).

In the cat, the histology was like that of the integument of the dog. The paw pad, however, was smooth, without multiple small protuberances called conical papillae observed in the dog paw pad (Figure 1(B)). The dermal papillae were apparently smaller than those of dogs (Figure 2(B)). Encapsulated sensory ending such as Pacinian corpuscles were not detected in any of the samples examined. Although, arteries and venules in the dermal layer are located close each other, they do not conform a periarterial venous plexus (Figure 3(B)). AVAs were not observed frequently unlike in the dog.

3.2. Corrosion Casts

In the dog paw pad, the principal source of blood to the

Figure 3. Histology of an artery surrounded by venules in the tunica adventitia forming a peri-arterial venous network (peri) in the canine footpad (A). Note venules forming a venous plexus (vp) around the artery (a). The ink injected was washed away during the procedure of the whole mount in the artery. Artery and veins (v) are arranged with a certain distance in the feline footpad (B). In this specimen Indian ink is not injected. H & E stain.

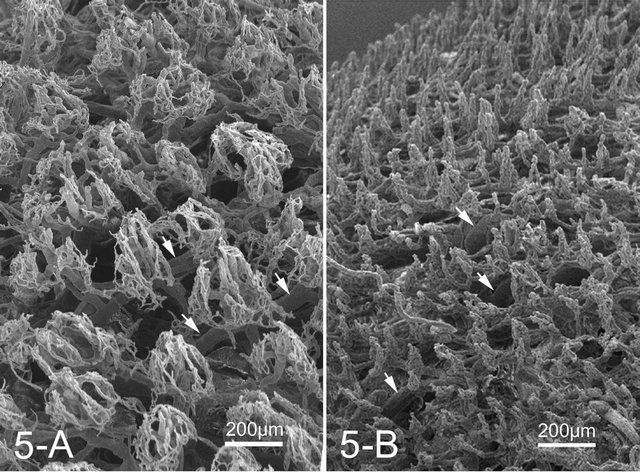

footpad was the axial palmar digital artery in the forepaw and axial plantar digital artery in the hindpaw, respectively. These arteries entered the integument and gave off numerous small arteries, some of which formed complicated arterial networks in the corium. The venous plexus were located on both sides of the artery and composed a vein-artery-vein triad structure (Figure 4(A)). From the venous plexus some of venules extended toward the artery and interconnected forming a single layered venule network wrapping and closely related to the artery, forming a peri-arterial venous network. In a cross-sectional view of the artery, the peri-arterial venous network had an overall sheath appearance (Figure 4(A)). The derma venous plexuses were much more prominent than the arterial plexus, since the veins were wider and much more abundant and freely interconnected than the arteries (Figure 5(A)). Some capillaries, after draining through the dermal papillae and the corium, conjoined into a series of venules forming a venous plexus running straight and parallel along the artery with few interconnections. Each papillary vascular unit consisted of central venules surrounded by fine capillaries. The capillaries of the papilla surrounding the central venules were connected to one another and formed a sheet of capillary plexus with a tapering cone-shaped structure just beneath the epidermis (Figure 5(A)). At the apex of the cone, the capillaries formed short arched loops and drained into the thick central venules, the diameter of which was about four times as that of the capillaries.

In the cat paw pad, capillaries supplying the dermal papillae and the dermal layer did not gather around veins as seen in the dog, but converge into post-capillary venules or join larger venules, forming an extensive venous

Figure 4. SEM image of a peri-arterial venous plexus (peri) showing capillaries and venules run parallel around the artery (a) forming a countercurrent heat exchanger in the canine footpad (A). While the feline footpad is devoid of the peri-arterial venous plexus (B). Artery and veins (v) run parallel but in the opposite direction (arrows). Abbreviations: Cn: capillary network, v: vein, vp: venous plexus accompanying arteries.

Figure 5. SEM image of overall view of the microvascular units in the canine (A) and feline (B) dermal papillae. Note a well developed dermal venous plexus (arrows).

plexus in the subpapillary layer. The veins ran parallel to arteries but in opposite directions. The peri-arterial venous plexus was not observed in the feline footpad, unlike those of the canine footpad (Figure 4(B)). The size of capillary networks in the dermal papillae was small with less capillaries than those of the dog (Figure 5(B)).

4. Discussion

4.1. Countercurrent Heat Exchanger

In the dog paw pad, the veins surround an artery and run parallel, forming a vein-artery-vein triad so that the arterial blood flows into the pad surface in the opposite direction to the venous blood flowing out. Venules are in intimate contact with one another. Such a system establishes a constant temperature gradient between arteries and veins and makes an effective countercurrent heat exchanger [7]. The warm arterial blood transfers its heat by simple conduction to the adjacent cool venous blood. In this way, blood-born heat is re-circulated back to the body core through the venous blood prior to losing heat to the environment. If a foot pad with a countercurrent heat exchanger is in a warm environment, the blood in that pad will be warm and the countercurrent heat exchanger will have little effect. When the foot pad is exposed to a cold environment, blood flow increases in the legs through regulated vasodilation in the foot pad [1,8,9]. Initially, vasodilation will accelerate heat loss due to increased blood flow to the cutaneous circulation and the countercurrent heat exchanger cannot retain the heat already in the paw [1], but continual heat loss is prevented by the countercurrent heat exchangers. This means that the dog has a warm body and cold paws during exposure to cold. Ice doesn’t stick to cold paws.

The principle of vascular countercurrent heat exchange is based on evidence presented in the following sections. The testicular artery, during its course through the spermatic cord, lies in the midst of the pampiniform venous plexus for cooling the testis [10]. Penguins mostly live in the extremely cold Antarctic [11] and whales and seals can swim in freezing water in the Arctic seas [5,6]. These animals also have countercurrent heat exchange networks in the feet, fins and flippers, respectively, to avoid losing their body heat [12]. In rabbits, the central auricular artery supplying blood to most of the auricular integument is surrounded by capillaries extended from those supplying the skin, suggesting a countercurrent heat exchange function [13].

4.2. Arteriovenous Anastomoses

Arteriovenous anastomoses (AVAs) play a role in allowing the shunting of blood away from the capillaries directly into the deeper cutaneous veins. The canine foot pad had numerous AVAs in the dermis. A large number of AVAs may be an adaptation preventing cold induced tissue damage in dogs standing for long periods on ice and snow as proposed for the large number of AVAs in the legs of penguins [14]. The vasculature of the canine paw pad is innervated by autonomic axons, which utilize dopamine causing vasodilation [9] and maximal vasodilation occurs at 0 degrees C [15]. When cold induced vasodilation of AVAs occurs, rapid flow of warm blood into the subcutaneous venous plexus is allowed, thereby the limbs maintain their temperature above the freezing point. Spontaneously, this AVA and capillary flow changes would prevent heat loss from the pad surface. In the dog heat loss through the paw pads would not be substantial, but AVAs may contribute to the maintenance of tissue metabolism by allowing perfusion of the feet when the dog is in a cold environment, such as standing on snow or ice. While, the constriction of AVAs occurs in a hot environment blood flow into the subcutaneous venous plexus is reduced to minimum and is changed into capillaries in the papillae, promoting heat dissipation from the skin surface [16]. The cat has few AVAs in the dermis, unlike those of the dog. The results suggest that the cat paw pad may not play an important role in thermoregulation as the cat would intend to have the relatively less warming needs of the footpad so that this might induce less cold tolerance at cold condition.

4.3. Well Developed Dermal Venous Plexus

Another characteristic feature in the foot pad is numerous veins and a prominent dermal venous plexus in both species. The venous plexus consists of thick veins freely anastomosing and forming a well-developed venous network, which acts as a potential blood reservoir [17].

The well-developed venous plexus may be an adaptation for reserving warm blood [17] and preventing cold induced tissue damage in dogs standing on snow and ice for long periods. A similar explanation has been proposed for the prominent venous sinus in the vibrissae of harbor seals (Phoca vitulina) and of the follicle crypts on the rostrum of the dolphin (Sotalia fluviatilis guianensis) [18] and cetacean eyes [19,20]. The venous sinuses around the vibrissal follicles reserve warm blood and functions as a heat conserving structure responsible for the maintenance of high tactile sensitivity at extremely low ambient temperatures. In both species, a well developed subcutaneous venous plexus have evolved in foot pad cutaneous tissue, which can hold large quantities of blood, augment heat delivery and protect tissues from frostbite.

In summary, in the dog originated from grey wolf (Canis lupus) living in a cold climate, the highly developed countercurrent heat exchange system and abundant AVAs and prominent dermal venous plexus located in the vascular system of the foot pad would seem to meet the thermal challenge that arises when the paw is exposed to low temperatures. This mechanism is augmented by vasodilation of the limb vessels, increasing blood flow to the pad surface. The domestic dog may bring about such an adaptation from the ancestors of the domestic dog lived in cold climates. While, cat domesticated from wildcat (Felis silvestris) living in a desert in Libya lacked the countercurrent heat exchange system and had few AVAs. This may explain that the cat has the relatively less warming needs of the footpad so that the animal is vulnerable to a cold environment such as standing on snow or ice. Surface with conical protrusion seen in the canine footpad may play a role in gripping snow or ice and may make an air layer preventing direct contact with snow or ice.

NOTES