1. Introduction

The study of multi-objective programming problems was very active in recent years. The minimum (efficient, Pareto) solution is an important concept in mathematical models, economics, decision theory, optimal control and game theory (see, for example, [1]). In most works, an assumption of convexity was made for the objective functions. Very recently, some generalized convexity has received more attention (see, for example, [2-6]). A significant generalization of convex functions is invex function introduced first by Hanson [7], which has greatly been applied in nonlinear optimization and other branches of pure and applied sciences.

The concept of B-invex functions was proposed by [8] as generalization of convex functions; these functions were extended to quasi B-invex, and pseudo B-invex functions. Many functions seem to be B-invex, but they are not, and many non B-invex functions are able to get B-invex by choosing a suitable condition. Based on the previous discussion, Tarek [9] introduced a new class of B-invex functions, this class called roughly B-invex functions.

Inspired and motivated by above works, the purpose of this paper is to formulate a multi-objective programming problem which it involves roughly B-invex functions. An efficient solution for considered problem is characterized by weighting and ε-constraint approaches. In the end of the paper, we obtain sufficient and necessary conditions for a feasible solution to be an efficient or properly efficient solution for this kind of problems. Let us survey, briefly, the definitions and some results of roughly B-invexity.

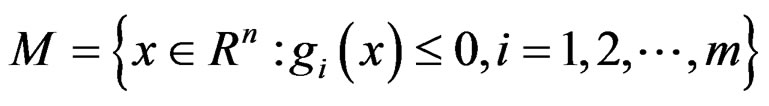

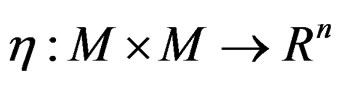

Definition 1 [10]

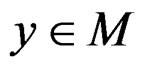

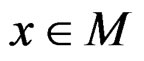

Let . The set M is said to be B-invex with respect to

. The set M is said to be B-invex with respect to  at

at  if there exists

if there exists

such that

such that , for each

, for each , and

, and .

.

M is said to be B-invex set with respect to η if M is B-invex at each  with respect to the same η.

with respect to the same η.

Note that, as in convex set, the intersection of finite (or infinite) family of B-invex sets is B-invex but the union is not necessarily B-invex set. Also, the sum of B-invex sets and the multiplying a B-invex set by a real number are again B-invex sets. Every B-invex set with respect to  is an invex set when b = 1; but the converse is not necessarily true.

is an invex set when b = 1; but the converse is not necessarily true.

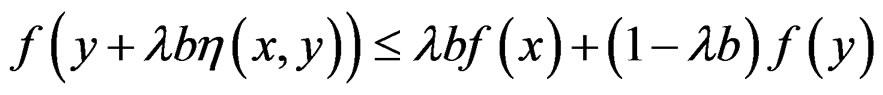

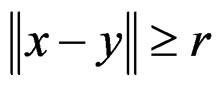

Definition 2 [9]

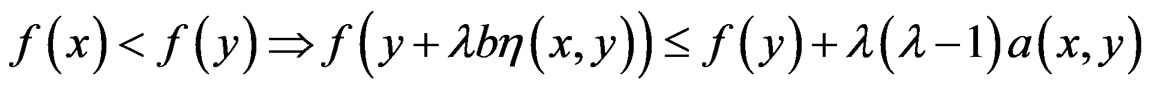

A numerical function f , defined on a B-invex subset M of Rn, is said to be roughly B-invex with respect to  with roughness degree r at

with roughness degree r at  if there exists

if there exists , such that

, such that

for each

for each , and

, and  such that

such that .

.

f is said to be roughly B-invex on M with respect to  if it is roughly B-invex at each

if it is roughly B-invex at each  with respect to the same

with respect to the same .

.

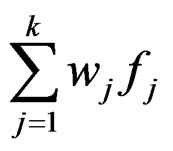

Every invex function, with respect to η is roughly B-invex function with respect to same η, where b (x, y) = 1; but the converse is not necessarily true. If the functions  are all roughly B-invex with respect to

are all roughly B-invex with respect to  with roughness degree

with roughness degree  on a B-invex set

on a B-invex set , then the function

, then the function

is roughly B-invex with respect to same η with roughness degree

on M for ai ≥ 0. If  is roughly B-invex with respect to

is roughly B-invex with respect to  with roughness degree r, on B-invex set

with roughness degree r, on B-invex set , then for any real number

, then for any real number  the level set

the level set  is B-invex set. A numerical function f defined on a B-invex set

is B-invex set. A numerical function f defined on a B-invex set  is roughly B-invex function with respect to

is roughly B-invex function with respect to  with roughness degree r if and only if epi(f) is a B-invex set. If

with roughness degree r if and only if epi(f) is a B-invex set. If  is a family of numerical functions, which are roughly B-invex with respect to

is a family of numerical functions, which are roughly B-invex with respect to  with roughness degree r and bounded from above on a B-invex set

with roughness degree r and bounded from above on a B-invex set , then the numerical function

, then the numerical function

is a roughly B-invex with respect to same η with roughness degree r on M. If  is a differentiable roughly B-invex function with respect to

is a differentiable roughly B-invex function with respect to  with roughness degree r, at

with roughness degree r, at , then there exists a function

, then there exists a function , such that

, such that

for each

for each  such that

such that .

.

Definition 3 [9]

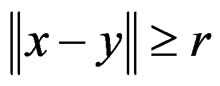

A numerical function f, defined on a B-invex subset M of Rn, is said to be quasi roughly B-invex with respect to  with roughness degree r at

with roughness degree r at , if there exists

, if there exists , such that

, such that

for each

for each , and

, and  such that

such that .

.

f is said to be quasi roughly B-invex on M with respect to  if it is roughly B-invex at each

if it is roughly B-invex at each  with respect to the same

with respect to the same .

.

A  is quasi roughly B-invex with respect to η: M × M → Rn with roughness degree r, on

is quasi roughly B-invex with respect to η: M × M → Rn with roughness degree r, on , if and only if the level set

, if and only if the level set

is B-invex set. A roughly B-invex function, with respect to  with roughness degree r is quasi roughly B-invex function with respect to same η with roughness degree r. Let

with roughness degree r is quasi roughly B-invex function with respect to same η with roughness degree r. Let  be B-invex set, if

be B-invex set, if  is differentiable quasi roughly B-invex with respect to

is differentiable quasi roughly B-invex with respect to  with roughness degree r, at

with roughness degree r, at , then there exists a function

, then there exists a function , such that

, such that

for each

for each  such that

such that .

.

Definition 4 [9]

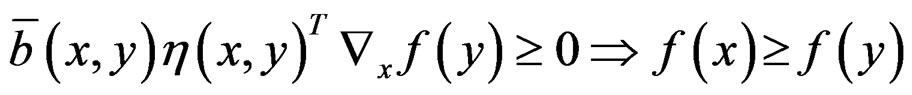

A numerical function f, defined on a B-invex subset M of Rn, is said to be pseudo roughly B-invex with respect to  with roughness degree r at

with roughness degree r at , if there exists

, if there exists , and, there exists a strictly positive function a: Rn × Rn → R such that

, and, there exists a strictly positive function a: Rn × Rn → R such that

for each  such that

such that .

.

If  is roughly B-invex function with respect to

is roughly B-invex function with respect to  with roughness degree r on B-invex set

with roughness degree r on B-invex set , then f is pseudo roughly B-invex function with respect to same η with roughness degree r on M. Let

, then f is pseudo roughly B-invex function with respect to same η with roughness degree r on M. Let  be B-invex set and

be B-invex set and  be a differentiable pseudo roughly B-invex with respect to

be a differentiable pseudo roughly B-invex with respect to with roughness degree r, at

with roughness degree r, at , then there exists a function

, then there exists a function , such that

, such that

for each

for each  such that

such that .

.

2. Problem Formulation

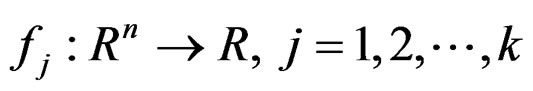

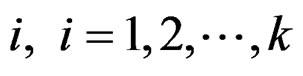

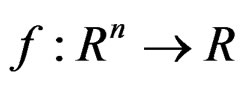

Let , and

, and  i = 1, 2, ···, m are real valued roughly B-invex functions on Rn. A roughly B-invex multi-objective programming problem is formulated as follows:

i = 1, 2, ···, m are real valued roughly B-invex functions on Rn. A roughly B-invex multi-objective programming problem is formulated as follows:

(P)

Definition 5 [11]

A feasible solution x for (P) is said to be an efficient solution for (P) if and only if there is no other feasible x for (P) such that, for some ,

,

.

.

Definition 6 [11]

An efficient solution  for (P) is a properly efficient solution for (P) if there exists a scalar

for (P) is a properly efficient solution for (P) if there exists a scalar  such that for each

such that for each , and each

, and each  satisfying

satisfying , there exists at least one

, there exists at least one  with

with  and

and

.

.

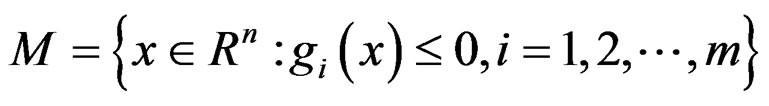

Lemma 1 [9]

If  is roughly B-invex with respect to

is roughly B-invex with respect to  with roughness degree r, on Rn, i = 1, 2, ···, m, then the set

with roughness degree r, on Rn, i = 1, 2, ···, m, then the set

is B-invex set.

Lemma 2 [9]

If  is quasi roughly B-invex with respect to

is quasi roughly B-invex with respect to  with roughness degree r, on Rn, i = 1, 2, ···, m, then the set

with roughness degree r, on Rn, i = 1, 2, ···, m, then the set

is B-invex set.

Lemma 3

Let . If

. If is a roughly B-invex function with respect to

is a roughly B-invex function with respect to  with roughness degree r on a B-invex set

with roughness degree r on a B-invex set , then the set

, then the set

is convexwhere

is convexwhere .

.

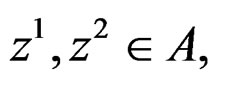

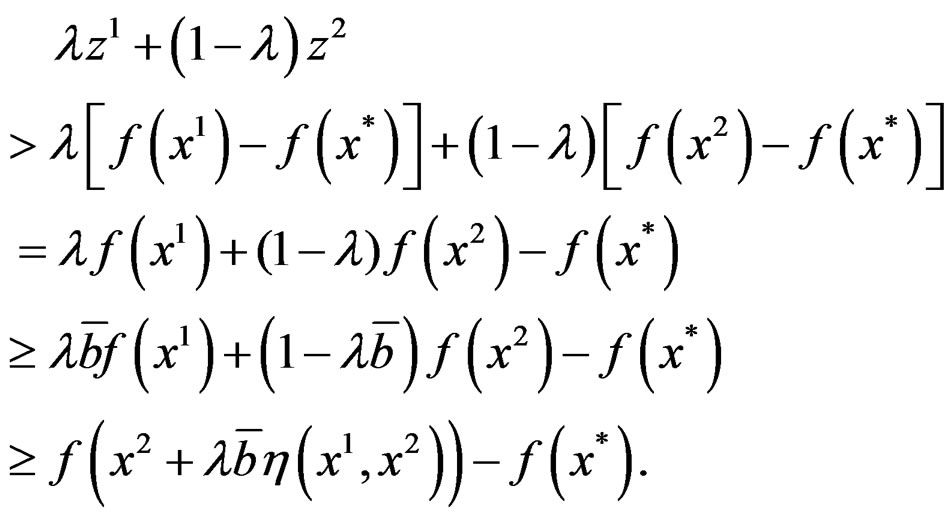

Proof. Let  then for

then for  and

and  we have

we have

Since f is a roughly B-invex function on a B-invex set M. Then , and hence A is convex set.

, and hence A is convex set.

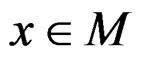

For a feasible point , we denote

, we denote  as the index set for binding constraints at x*, i.e.,

as the index set for binding constraints at x*, i.e., .

.

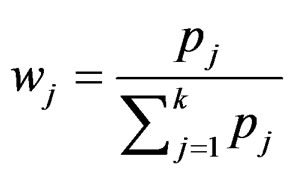

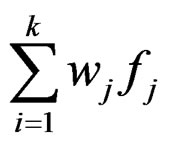

3. Characterizing Efficient Solutions by Weighting Approach

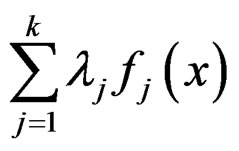

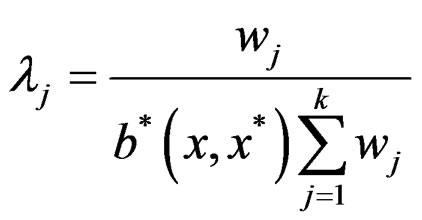

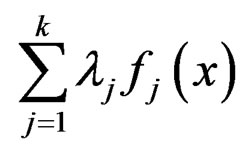

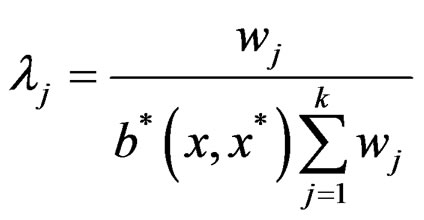

To characterizing an efficient solution for problem (P) by weighting approach [11] let us scalarize problem (P) to become in the form.

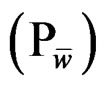

(Pw)  , s.t.

, s.t. where

where

and , j = 1, 2, ···, k are roughly B-invex with respect to

, j = 1, 2, ···, k are roughly B-invex with respect to  with roughness degree rj on B-invex set M.

with roughness degree rj on B-invex set M.

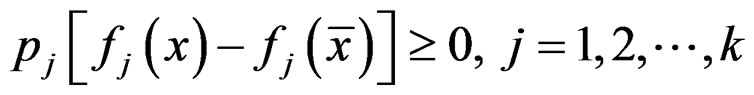

Theorem 1

If  is an efficient solution for problem (P), then there exist

is an efficient solution for problem (P), then there exist

such that  is an optimal solution for problem (Pw).

is an optimal solution for problem (Pw).

Proof. Let  be an efficient solution for problem (P), then the system

be an efficient solution for problem (P), then the system  j = 1, 2, ···, k has no solution

j = 1, 2, ···, k has no solution . Upon Lemma 3 and by applying the generalized Gordan theorem [12], there exist

. Upon Lemma 3 and by applying the generalized Gordan theorem [12], there exist  such that

such that

and

and  .

.

Denote  then

then  and

and  .

.

Hence  is an optimal solution for problem (Pw).

is an optimal solution for problem (Pw).

Theorem 2

If  is an optimal solution for

is an optimal solution for  corresponding to

corresponding to , then

, then  is an efficient solution for problem (P) if either one of the following two conditions holds:

is an efficient solution for problem (P) if either one of the following two conditions holds:

(i)  for all

for all ; or (ii)

; or (ii)  is the unique solution of

is the unique solution of .

.

Proof. To proof see V. Chankong, Y. Y. Haimes [11].

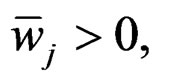

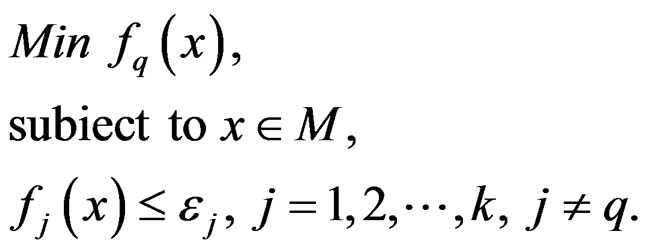

4. Characterizing Efficient Solutions by ε-Constraint Approach

An ε-constraint approach is one of the common approaches for characterizing efficient solutions of multiobjective programming problems [11]. In the following we shall characterizing an efficient solution for multiobjective roughly B-invex programming problem (P) in term of an optimal solution of the following scalar problem.

where  are roughly B-invex with respect to

are roughly B-invex with respect to  with roughness degree rj on B-invex set M.

with roughness degree rj on B-invex set M.

Theorem 3

If  is an efficient solution for problem (P), then

is an efficient solution for problem (P), then  is an optimal solution for problem

is an optimal solution for problem  corresponding to

corresponding to .

.

wang#title3_4:spProof.

Let  be not optimal solution for

be not optimal solution for  where

where  So there exists

So there exists

such that  ,

,

.

.

Thus,  is inefficient solution for problem (P) which is a contradiction. Hence

is inefficient solution for problem (P) which is a contradiction. Hence  is an optimal solution for problem

is an optimal solution for problem .

.

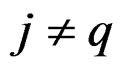

Theorem 4

Let  is an optimal solution of

is an optimal solution of  for all q = 1, 2, ···, k, where

for all q = 1, 2, ···, k, where , j = 1, 2, ···, k . Then

, j = 1, 2, ···, k . Then  is an efficient solution for problem (P).

is an efficient solution for problem (P).

wang#title3_4:spProof.

Since  is an optimal solution for

is an optimal solution for , for all q = 1, 2, ···, k. So, for each

, for all q = 1, 2, ···, k. So, for each , we get

, we get  q = 1, 2, ···, k.

q = 1, 2, ···, k.

This implies that the system  j = 1, 2, ···, k has no solution

j = 1, 2, ···, k has no solution , i.e.

, i.e.  is an efficient solution for problem (P).

is an efficient solution for problem (P).

5. Sufficient and Necessary Conditions for Efficiency

In this section, we discuss the sufficient and necessary conditions for a feasible solution x* to be efficient or properly efficient for problem (P) in the form of the following theorems.

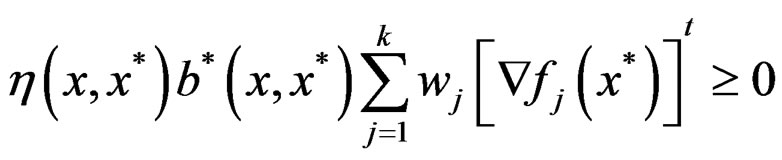

Theorem 5

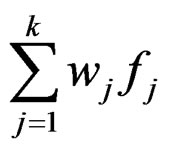

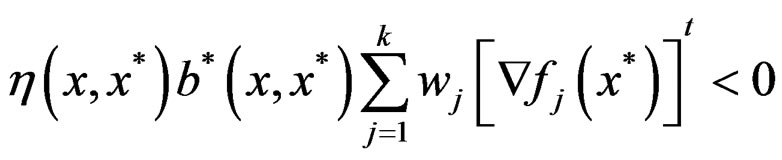

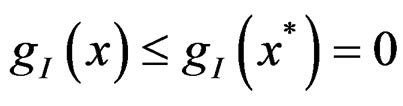

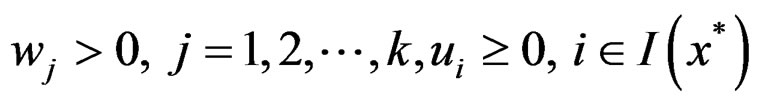

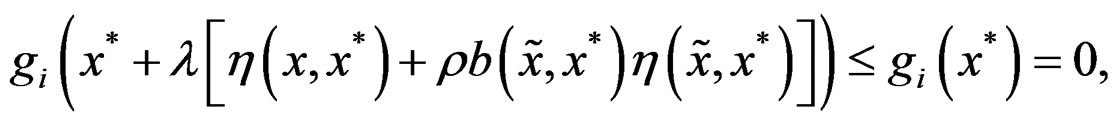

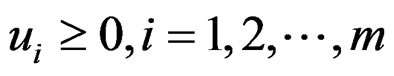

Suppose there exists a feasible solution x* for (P), and scalars , such that

, such that

. (1)

. (1)

If , j = 1, 2, ···, k are roughly B-invex with respect to

, j = 1, 2, ···, k are roughly B-invex with respect to  with roughness degree r at x* and gi,

with roughness degree r at x* and gi,  is roughly B-invex with respect to same η with roughness degree ri at x*. Then x* is a properly efficient solution for problem (P).

is roughly B-invex with respect to same η with roughness degree ri at x*. Then x* is a properly efficient solution for problem (P).

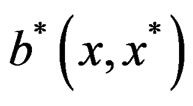

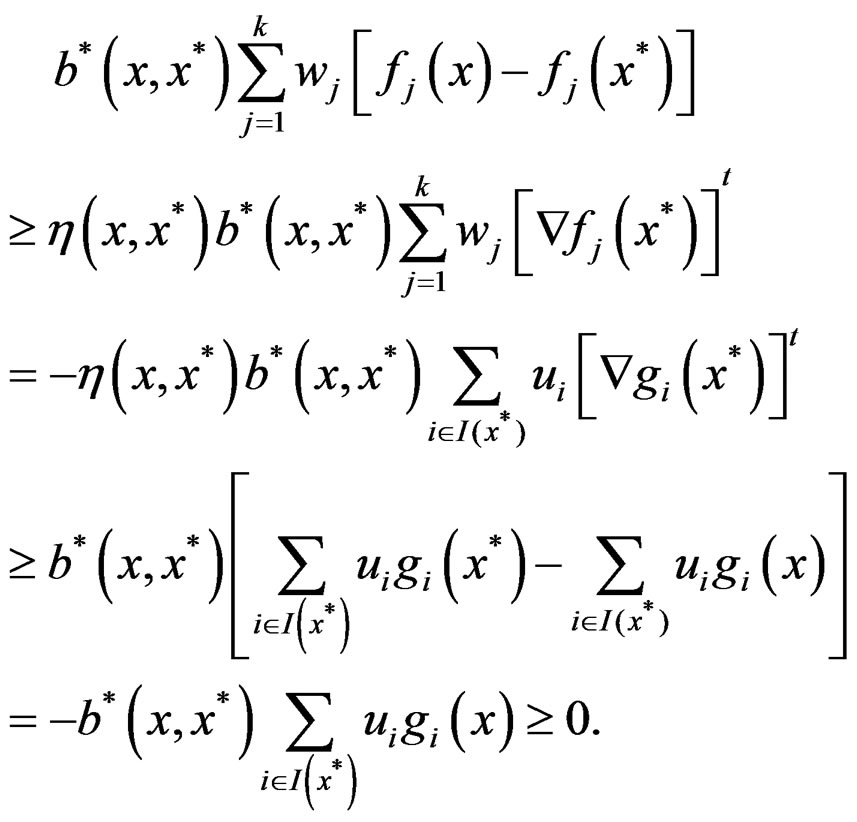

Proof.

Since , j = 1, 2, ···, k and

, j = 1, 2, ···, k and  are roughly B-invex with respect to same η, then there exists a function

are roughly B-invex with respect to same η, then there exists a function  such that

such that

by (1) for each  such that

such that

.

.

Thus,  for all

for all , which implies that x* is the minimizer of

, which implies that x* is the minimizer of

such that

under the constraint  where

where . Hence, from Theorem (4.11) of [11], x* is a properly efficient solution for problem (P).

. Hence, from Theorem (4.11) of [11], x* is a properly efficient solution for problem (P).

Theorem 6 Let x* be a feasible solution for (P). If there exist scalars ,

,

such that the triplet (x*, wi, ui) satisfies (1) of Theorem (5),

such that the triplet (x*, wi, ui) satisfies (1) of Theorem (5),

is strictly roughly B-invex with respect to η: M × M → Rn with roughness degree r at x* and gi,  is roughly B-invex with respect to same η with roughness degree ri at x*. Then x* is an efficient solution for problem (P).

is roughly B-invex with respect to same η with roughness degree ri at x*. Then x* is an efficient solution for problem (P).

Proof.

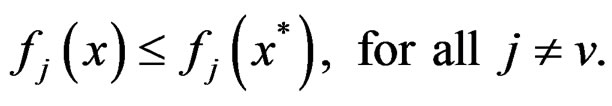

Suppose that x* is not an efficient solution for (P). Then, there exists a feasible , and index v such that

, and index v such that

Since

is strictly roughly B-invex with respect to η with roughness degree r at x*, then there exists a function  such that

such that

. (2)

. (2)

Also, roughly B-invexity of gi,  with respect to same η at x* with roughness degree ri implies

with respect to same η at x* with roughness degree ri implies

i.e.

i.e.  , (3)

, (3)

such that . Adding (2) and (3), contradicts (1). Hence, x* is an efficient solution for problem (P).

. Adding (2) and (3), contradicts (1). Hence, x* is an efficient solution for problem (P).

Remark 1

Similarly as in Theorem (5), it can be easily seen that x* becomes properly efficient solution for (P), in the above theorem, if wj > 0, for all j = 1, 2, ···, k.

Theorem 7

Suppose there exists a feasible solution x* for (P), and scalars wi > 0, j = 1, 2, ···, k,  such that (1) of Theorem (5) holds. If

such that (1) of Theorem (5) holds. If

is pseudo roughly B-invex with respect to  with roughness degree r at x* and gI is quasi roughly B-invex with respect to same η with roughness degree rI at x*. Then x* is a properly efficient solution for problem (P).

with roughness degree r at x* and gI is quasi roughly B-invex with respect to same η with roughness degree rI at x*. Then x* is a properly efficient solution for problem (P).

Proof.

Since , and gI are quasi roughly B-invex with respect to η with roughness degree rI at

, and gI are quasi roughly B-invex with respect to η with roughness degree rI at , then there exists a function

, then there exists a function  such that

such that

for all

for all  such that

such that . By using (1)we have

. By using (1)we have

which implies

since

since

is pseudo roughly B-invex with respect to same η with roughness degree r at x* which implies that x* is the minimizer of

such that

under the constraint  where

where  ≥ max(r, ri). Therefore, x* is a properly efficient solution for problem (P).

≥ max(r, ri). Therefore, x* is a properly efficient solution for problem (P).

Theorem 8

Suppose that there exist a feasible solution x* for (P) and scalars ,

,

,

,  such that (1) of Theorem (5) holds. Let

such that (1) of Theorem (5) holds. Let

be strictly pseudo roughly B-invex with respect to  with roughness degree r at

with roughness degree r at  and gI be quasi roughly B-invex with respect to same η with roughness degree rI at x*. Then x* is an efficient solution for problem (P).

and gI be quasi roughly B-invex with respect to same η with roughness degree rI at x*. Then x* is an efficient solution for problem (P).

Proof. Suppose that x* is not an efficient solution for (P).Then, there exists a feasible x for (P), and index v such that  then there exists a function

then there exists a function  such that,

such that,

Strictly pseudo roughly B-invexity of

Strictly pseudo roughly B-invexity of

implies that

for all  such that

such that . Since gI is quasi roughly B-invex with respect to same η with roughness degree rI at

. Since gI is quasi roughly B-invex with respect to same η with roughness degree rI at  and

and then

then  for all

for all  such that

such that

.

.

The proof now similar to the proof of Theorem (6).

Remark 2

Similarly as in Theorem (7), it can be easily seen that x* becomes properly efficient solution for (P), in the above theorem, if .

.

Theorem 9

Suppose there exists a feasible solution x* for (P), and scalars  such that (1) of Theorem (5) holds. Let

such that (1) of Theorem (5) holds. Let

be pseudo roughly B-invex with respect to  with roughness degree

with roughness degree  at x* and

at x* and  be quasi roughly B-invex with respect to same η with roughness degree

be quasi roughly B-invex with respect to same η with roughness degree  at x*. Then x* is a properly efficient solution for problem (P).

at x*. Then x* is a properly efficient solution for problem (P).

Proof. The proof is similar to the proof of Theorem (7).

Theorem 10

Suppose that there exist a feasible solution x* for (P) and scalars ,

,

such that (1) of Theorem (5) holds. If

such that (1) of Theorem (5) holds. If ,

,

is quasi roughly B-invex with respect to  with roughness degree r at x* and

with roughness degree r at x* and  is strictly pseudo roughly B-invex with respect to same η with roughness degree rI at x*. Then x* is an efficient solution for problem (P).

is strictly pseudo roughly B-invex with respect to same η with roughness degree rI at x*. Then x* is an efficient solution for problem (P).

Proof. The proof is similar to the proof of Theorem (8).

Remark 3

Similarly as in Theorem (7), it can be easily seen that x* becomes properly efficient solution for (P), in the above theorem, if .

.

Theorem 11 (Necessary Optimality Criteria)

Assume that x* is a properly efficient solution for problem (P). Assume also that there exist a feasible point  for (P) such that

for (P) such that , and each

, and each  is roughly B-invex with respect to η: M × M → Rn with roughness degree ri at x*. Then, there exists scalars

is roughly B-invex with respect to η: M × M → Rn with roughness degree ri at x*. Then, there exists scalars  and

and , such that the triplet

, such that the triplet  satisfies

satisfies

. (4)

. (4)

Proof. Let the following system

. (5)

. (5)

has a solution for every . Since by the assumed Slater-type condition,

. Since by the assumed Slater-type condition,

and then from roughly Bi-invexity of gi at

and then from roughly Bi-invexity of gi at  with respect to η, there exists a function

with respect to η, there exists a function  such that

such that

. (6)

. (6)

Therefore from (5) and (6)

for all

for all . Hence for some positive λ small enough

. Hence for some positive λ small enough

Similarly, for , and for

, and for  small enough

small enough

.

.

Thus, for λ sufficiently small and all

is feasible for problem (P). For sufficiently small , (5) gives

, (5) gives

. (7)

. (7)

Now, for all  such that

such that

(8)

(8)

Consider the ratio (see Equation (9))

From (5), . Similarly,

. Similarly, ; but, by (8)

; but, by (8) .

.

Thus, the ratio in (9) becomes unbounded, contradicting the proper efficiency of x* for (P). Hence, for each q = 1, 2, ···, k, the system (5) has no solution. The result then follows from an application of the Farkas Lemma as in [12], namely

.

.

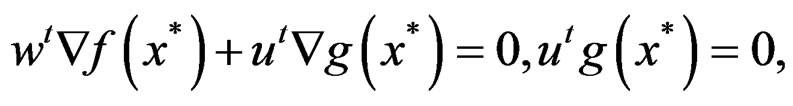

Theorem 12

Assume that x* is an efficient solution for problem (P) at which the Kuhn-Tucker constraint qualification is satisfied. Then, there exist scalars

,

, such that

such that

,

, .

.

Proof.

Since every efficient solution is a weak minimum, then by applying Theorem (2.2) of Weir and Mond [13] for x*, we get, there exists  such that

such that

. (9)

. (9)

, where

, where .

.