Trends in U.S. Primary Care Provider Patient Advice Against Secondhand Smoke Exposure: 2008-2010 ()

1. Introduction

Tobacco use in any form jeopardizes health. Americans have been hearing this and other messages about the dangers of tobacco use for more than 50 years. The United States Department of Health and Human Services has documented overwhelming and conclusive biologic, epidemiologic, behavioral, and pharmacologic evidence to support that statement [1]. Information about the health consequences of smoking has continued to grow, with indisputable evidence suggesting more than 1000 people are killed every day in the United States because of the harmful effects of cigarettes, mostly by smoking-related diseases such as heart disease, stroke, chronic lung disease, and cancer [1].

According to the 2006 Surgeon’s General Report, The Health Consequences of Involuntary Exposure to Tobacco Smoke, exposure to secondhand smoke (SHS) adversely affects the cardiovascular system, and causes coronary heart disease and lung cancer. Furthermore, no level of exposure is safe [2]. Evidence has shown that the concentrations of many cancer-causing and toxic chemicals are higher in SHS than in the smoke inhaled by smokers [2]. As a result, SHS causes harmful effects on the cardiovascular system, and can increase the risk for heart attack, even among nonsmokers [3].

In the 2010 Surgeon General’s Report, How Tobacco Smoke Causes Disease, researchers concluded that breathing SHS causes immediate damage to the lungs due to the inhalation of a multitude of fine particles, gases, and chemicals that result in irritation and inflammation of endothelial tissue (tissue lining body cavities) [4]. People living with chronic illnesses such as asthma, emphysema, chronic bronchitis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or other respiratory conditions, may experience a worsening of symptoms (e.g. wheeze, shortness of breath, cough) when exposed to SHS [5]. It has been also determined that babies of pregnant women who are exposed to SHS may have decreased birth weight and have a higher risk of sudden infant death syndrome [2,6]. Because SHS exposure affects the air quality in the immediate surroundings, vulnerable populations—such as young children who reside in homes with parents who smoke—have higher prevalence of sudden infant death syndrome, ear problems, respiratory infections, and asthma attacks than those who live in nonsmoking homes [2,3].

One opportunity for providing advice about the dangers of SHS is the primary health care visit, where primary care providers (PCPs) can educate patients about the adverse outcomes of SHS exposure. Little is known about what health professionals say to patients regarding SHS exposure, so our research examines three situations: what providers say to patients with children, regarding the need to prevent exposure of the children to SHS; providers’ advise to smokers, about the need to avoid exposing others to SHS in homes and cars; and providers’ advise to nonsmokers about avoid SHS exposure. Using findings from a Web-based physician survey, we report on the prevalence in 2008, 2009, and 2010 of PCPs’ advise to patients about SHS exposure.

2. Method

The physician sample of the DocStyles survey consisted of family/general practitioners, general internists, and obstetrician/gynecologists. Physicians responded to a series of identical questions on provider advice practices in each of the 3 years. DocStyles is an annual Web-based survey conducted by Epocrates Incorporated (http://www. epocrates.com/honors). Respondents were volunteers from the Epocrates Honors Panel, an opt-in panel of medical practitioners [7]. Other studies using DocStyles have reported details on the sampling methodology [8,9]. Each physician’s first name, last name, date of birth, and medical school and graduation data were verified by comparison with the American Medical Association’s (AMA’s) master file at the time of panel registration. Epocrates randomly selected a sample of eligible physicians from their main database to load into their invitation database. The sample was drawn to match AMA master file proportions for age, gender, and region. Physicians were screened to include only those who practice in the United States; actively see patients; work in an individual, group, or hospital practice; and who have been practicing medicine for at least 3 years. Respondents were not required to participate and could exit the survey at any time. The estimated time for online completion of the survey varied by specialty and ranged from approximately 19 to 30 minutes. Invitations were sent out to the Web-based survey.

The DocStyles survey instrument was developed by Porter Novelli with technical assistance provided by federal public health agencies and other non-profit and for-profit clients. The survey contained over 100 questions, some with multiple subparts. The survey was designed to provide insight into healthcare providers’ attitudes and counseling behaviors on a variety of health issues. The 2008, 2009, and 2010 surveys were administered in July during each of the 3 years; the response rates were 22.0%, 45.8%, and 45.9%, respectively. Physicians were paid an honorarium of $40 to $95 for completing the survey.

2.1. Survey Items

PCP personal characteristics consisted of sex, specialty (e.g., family/general practitioner, internist, obstetrician/ gynecologist), age (≤40, >40), and race/ethnicity (white, non-Hispanic, other). Practice characteristics such as number of patients seen per week (≤100, >100), number of years in practice (≤10, >10), and practice setting type (individual, group, hospital) were also collected. We examined reported data on all personal and practice characteristics provided.

Secondhand Smoke Strategies

Three questions probed PCPs about SHS exposure. First, physicians were asked, Do you advise your patients with children to keep their children from being exposed to smoke from cigarettes or other tobacco products (that is, secondhand smoke)? Respondents were asked two additional SHS questions: Do you advise your patients who do not smoke tobacco or use other tobacco products to avoid being exposed to secondhand smoke? and Do you advise your patients who smoke tobacco or use other tobacco products to create smoke-free homes and cars? Response options for all three questions were “yes” or “no”.

2.2. Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, North Carolina) and SUDAAN (Version 9.0; Research Triangle Institute, Research Triangle Park, NC) was used to account for the random sample design. We compared the respondents with non-respondents and did not find any differences in the personal and practice characteristics. Prevalence (%) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were reported for advising against SHS exposure, and were categorized by PCP personal and practice characteristics. Multivariate logistic regression models were used to calculate odds ratios (ORs) for offering patients advice regarding SHS exposure (versus lack of advice). Using 2010 data, separate logistic regression models were run to examine individual comparisons (demographics, patients per week, years in practice and practice setting) for providing advice towards SHS exposure. Statistical significance was determined at p < 0.05.

3. Results

Data for each of the 3 years surveyed consisted of approximately 1250 health care providers (Table 1). The majority of the Web-based sample was male, family/general practitioners, over 40 years of age, and white nonHispanic. We examined 100 patients per week or less, were in practice over 10 years, and were in group practice settings.

3.1. Advice to Patients Who Were Also Parents

The prevalence of advice to patients with children to keep their children from being exposed to SHS was high and remained high over the 3 years: 94.0% in 2008, 91.7% in 2009, and 93.6% in 2010 (Table 2). Among specific primary care specialties, the prevalence was lowest among obstetrician/gynecologists (OBs/GYNs): 86.6% (2008), 88.4% (2009), and 89.2% (2010). Among other racial/ethnic PCPs, the prevalence was 95.8% (2008), 88.4% (2009), and 91.7% (2010). The prevalence of PCPs’ advice for those in practice 10 years or more was 92.5% (2008), 92.2% (2009), and 93.4% in 2010.

Table 1. Characteristics of primary care provider sample— DocStyles 2008-2010.

3.2. Advice to Smokers

Overall, PCPs’ advice to smokers to avoid SHS exposure in their homes and cars varied little over the 3-year period: 83.5% in 2008, 79.7% in 2009, and 85.5% in 2010 (Table 3). For this same period, among OBs/GYNs, the prevalence of asking smokers to avoid SHS exposure in their home and car was 74.7% in 2008, 72.8% in 2009, and 84.3% in 2010. Among PCPs over 40 years of age, the prevalence of asking smokers to avoid SHS exposure in their home and car was 81.5% in 2008, 80.6% in 2009, and 86.2% in 2010. For white non-Hispanic PCPs, the prevalence of asking smokers to avoid SHS exposure in their homes and cars was 83.9% in 2008, 80.2% in 2009, and 87.6% in 2010. For PCPs in practice for more than 10 years, the prevalence of asking smokers to avoid SHS exposure in their homes and cars was 81.5% in 2008, 81.1% in 2009, and 85.6% in 2010.

3.3. Advice to Nonsmokers

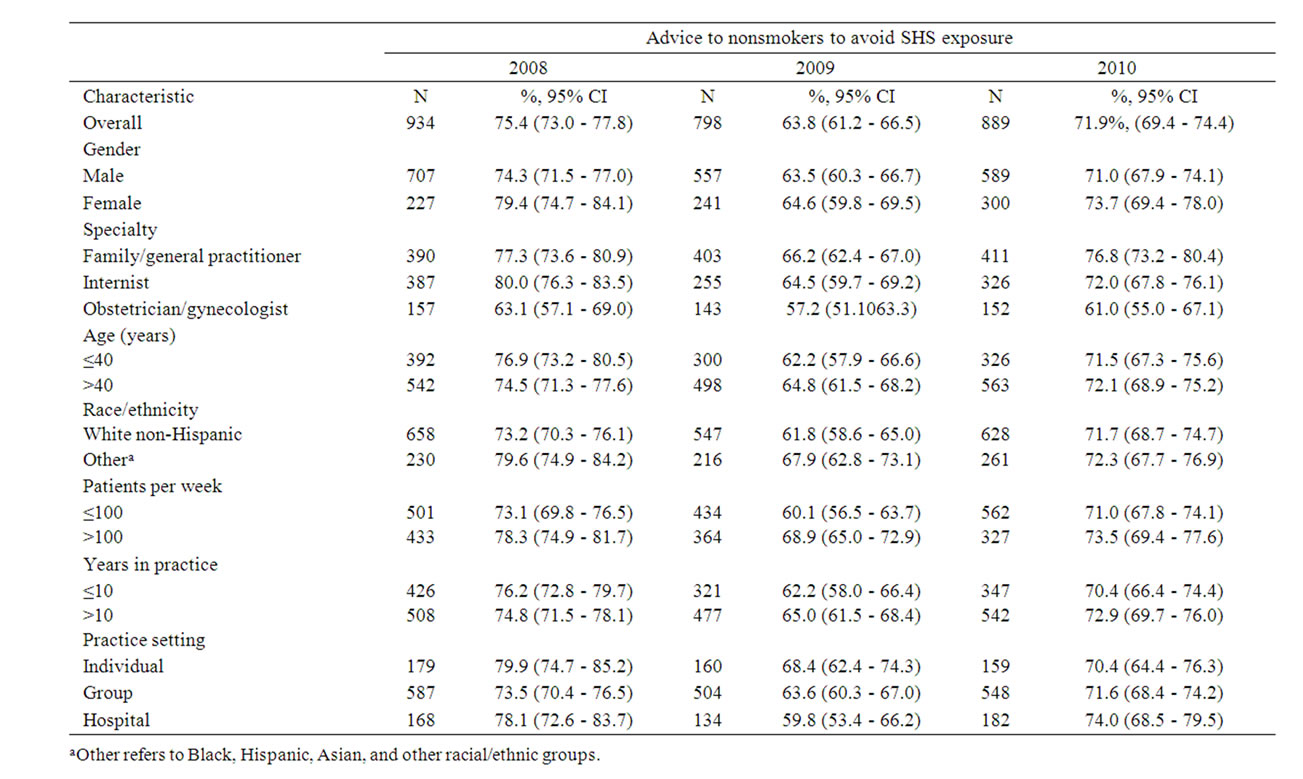

Among the SHS questions about PCP practices, the prevalence of advising nonsmokers to avoid general exposure to SHS was lowest: 75.4% in 2008, 63.8% in 2009, and 71.9% in 2010 (Table 4). Over this same period, among internists, the prevalence of advising nonsmokers to avoid any exposure to SHS was 80.0% in 2008, 64.5% in 2009, and 72.0% in 2010. The prevalence of PCPs’ advice to nonsmokers to avoid general exposure to SHS among other race/ethnicity PCPs was 79.6% in 2008, 67.9% in 2009, and 72.3% in 2010. The prevalence of PCP advice practices to nonsmokers to avoid general exposure to SHS among those in practice 10 years or less was 76.2% in 2008, 62.2% in 2009, and 70.4% in 2010. The prevalence of PCPs advice practices to nonsmokers to avoid general exposure to SHS among those in individual practice settings was 79.9% in 2008, 68.4% in 2009, and 70.4% in 2010.

3.4. Comparisons of Practices by Sex, Specialty, and Other Factors

Logistic regression analysis of PCPs advice practices toward SHS in 2010 showed that female PCPs were more likely than male PCPs (Table 5) to provide advice to smokers to avoid SHS exposure in their homes and cars (OR = 1.65; 95% CI = 1.15 - 2.37). Internists were less likely than family/general practitioners to advise patients with children against SHS exposure (OR = 0.43; 95% CI = 0.23 - 0.78), and to advise smokers to avoid SHS exposure in their homes and cars (OR = 0.47; 95% CI = 0.32 - 0.69). OBs/GYNs were also less likely to advise patients with children against SHS exposure (OR = 0.27; 95% CI = 0.14 - 0.50), to advise to smokers to avoid SHS exposure in their homes and cars (OR = 0.55; 95%

Table 2. Estimates of advice to patients with children to keep their children from being exposed to secondhand smoke by primary care providers—DocStyles 2008-2010.

Table 3. Estimates of advice to smokers to avoid secondhand smoke exposure in their home and car by primary care providers—DocStyles 2008-2010.

Table 4. Estimates of advice to nonsmokers to avoid general exposure of secondhand smoke by primary care providers— DocStyles 2008-2010.

Table 5. Logistic regression of primary care providers’ advice towards exposure of secondhand smoke—DocStyles, 2010.

CI = 0.35 - 0.87), and to provide advice to nonsmokers to avoid general exposure to SHS (OR = 0.47; 95% CI = 0.34 - 0.65) compared with family/general practitioners. Other race/ethnicity PCPs were also less likely than whites to provide advice to smokers to avoid SHS exposure in their homes and cars (OR = 0.58; 95% CI = 0.41 - 0.81). Logistic regression analyses were performed in 2008 and 2009 and similar patterns were found (data not shown).

4. Discussion

These Web-based data show that nearly all physicians reported that they discuss SHS risks with their patients. Overwhelmingly, as many as 90% of PCP advised patients with children to keep their children from being exposed to SHS, 80% advised patients who smoke to avoid exposing others to SHS in their homes and cars, and 70% advised nonsmokers to avoid general exposure to SHS. Although there are few other national studies on this topic, Burnett and Young found that 96% of providers reported that they sometimes/often screen for any SHS exposure [10]. Physicians are looking for opportunities to more consistently address, in their clinical practices, the health risks of SHS [11]. Since patients are open to SHS counseling and adults who are counseled on SHS exposure report higher rates of satisfaction with their care, PCPs should screen for tobacco use and address SHS risks.

Since the mid-2000s, there has been an increased awareness of the effects of SHS [2], which likely has contributed to recommendations to clinicians to address this issue with their patients. Historically, the first government report to conclude that SHS caused disease was the 1986 Surgeon’s General Report [12]; this was updated in 2006 with a second Surgeon General’s Report dedicated to the adverse health effects of SHS [2]. Additionally, primary care medical societies have called on their physician members to address the dangers of SHS with their patients. For example, in a 2009 policy statement the American Academy of Pediatrics recommended documentation of SHS exposure at all clinical encounters [13]; the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists 2010 committee opinion recommended that pregnant women avoid SHS exposure [14], and the 2009 position paper by the American Academy of Family Practice recommended that their physicians counsel patients to avoid establishments that permit smoking and to request that family members not smoke in their homes or vehicles [15]. Finally, the Public Health Service Update in 2008, Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence, recommended that clinicians screen for tobacco use and address SHS risks with their primary care patients [16].

While helpful, these recommendations vary across the physician specialty groups by the specific clinical actions proposed and the degree to which procedures are emphasized for specialty members. It is also possible that training of family/general practitioners concentrates more on preventive medicine, which may explain why these specialties advise patients against tobacco more often than internists or obstetrician/gynecologists. Family/general practitioners regularly encounter a high volume of patients and frequently deliver primary care to children, which may account for higher prevalence of advice against home and car exposures and general exposure among nonsmokers. Further, clarity and harmonization are needed among various recommendations for SHS exposure as it relates to tobacco control efforts. Findings from a review on the treatment of smokers in the health care setting [17] suggests that it would be advantageous to society if physicians would incorporate advice towards reducing SHS exposure into their counseling strategy.

Several limitations apply to this study. First, because data were obtained from convenience samples of selfselected healthcare providers who responded to the e-mail invitation to be part of the Epocrates Honor Panel; thus, our findings are not necessarily generalizeable beyond responders in terms of being nationally representative. Second, self-reported data may introduce social desirability bias of prevention practices among physicians. Self-reported data have also been found to overestimate observational study findings [18,19]. Third, we cannot make inferences about physicians’ routine practices in advising about exposure to SHS, as these data do not ask about frequency of counseling, amount of tobacco products, or number of years patients were using tobacco. Also, since the questions relied on recall, they may not accurately capture providers’ actual behavior. Fourth, the response rates reported in this web-based survey are comparable to other studies that have used mail-in surveys [20,21], but there still may be a nonresponse bias due to relatively low response rates. However, this is the first analysis that we are aware of that examines the prevalence of PCPs practices in advising on SHS exposure over time in recent years. The strength of our study is the large number of PCPs participating each year; this facilitated generation of estimates by demographic and practice characteristics on the reporting of providing SHS advice.

5. Conclusions

Findings suggest that a high proportion of primary care physicians address their patients SHS exposure risk. In this sample, we found that PCP advice practices included: advising patients with children to keep their children from being exposed to SHS (94.0% in 2008, 91.7% in 2009 and 93.4% in 2010); advising patients who smoke to avoid exposing others to SHS in their homes and cars (83.5% in 2008, 79.7% in 2009 and 85.5% in 2010); and advising nonsmokers to avoid general exposure to SHS (75.4% in 2008, 63.8% in 2009 and 71.9% in 2010).

Based on our finding that OBs/GYNs are less likely to engage in SHS counseling than other health care providers, promotion of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommendations [14], in addition to further investigative solutions for ways to improve counseling rates, are needed. Because of the health consequences of SHS exposure, PCPs should be encouraged to address SHS exposure consistently with their patients.

6. Acknowledgements

The authors thank Deanne Weber for providing technical assistance with the data.

NOTES