Creative Education

Vol.06 No.20(2015), Article ID:61438,12 pages

10.4236/ce.2015.620222

The Impact of Mindfulness Meditation on Academic Well-Being and Affective Teaching Practices

Tahereh Ziaian1, Janet Sawyer2, Nina Evans3, David Gillham4

1School of Nursing and Midwifery, University of South Australia, Adelaide, Australia

2Centre for Regional Engagement, University of South Australia, Adelaide, Australia

3School of Information Technology and Mathematical Sciences, Adelaide, Australia

4School of Nursing and Midwifery, Flinders University of South Australia, Adelaide, Australia

Copyright © 2015 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

Received 9 September 2015; accepted 22 November 2015; published 25 November 2015

ABSTRACT

Using action research, this study investigated the impact of mindfulness meditation as used by academic staff on the affective domain of teaching and learning, and its impact on the psychological well-being of academic staff. Through convenience sampling technique, academic staff at the University of South Australia’s Centre for Regional Engagement were recruited to the study. Participants completed a mindfulness meditation program including meditation practice of five minutes twice a day for a nine-month period. Workshops and individual telephone interviews were conducted during this time, with early findings indicating that mindfulness meditation can increase staff awareness of the affective domain and promote mental well-being. The results also suggest strategies to promote affective teaching and learning within the tertiary environment.

Keywords:

Mindfulness, Mindfulness Meditation, Wellbeing, Affective Domain, Higher Education, Universities

1. Introduction

University education is rapidly changing in response to globalisation, technological development, cultural and social change. Academics are teaching increasingly larger numbers of students, in an environment of unprecedented access to information and rapid electronic communication. These factors combine to produce a learning environment where both staff and students may experience limited human interaction as electronic online communication becomes the primary means of interaction between staff and students. With online technologies often regarded as the most time efficient way to access new knowledge, the personal interactions between students and academics that are central to the learning process are now in jeopardy (Attwood, 2009) . According to Light (2006) , “today’s students are no longer the people our education system was designed to teach”. McInnis (2003) refers to these students as “multi-tasking, digitally connected”, but also found that 25% of first year students do not have significant contact with other students on campus, claiming that such “isolation is intellectually and emotionally limiting”. Universities have invested enormous resources in the development of online course content and cognitive, intellectual outcomes, with the measurement of cognitive abilities used as the basis for educational methods for many years (Birbeck & André, 2009) . However relatively less attention has been directed towards the emotional or affective aspects of learning, particularly in relation to online learning.Research conducted to determine the value of affective learning and teaching can provide insight into the practical implications for learning outcomes (Craig, 2011; Holland, 2006) , as well as the possibility that mindfulness meditation may increase psychological well-being. A review of mindfulness meditation and affective approaches, and the practical implications within educational institutions are necessary in order to determine the significance for students and academic staff.

The research described in this paper aimed to investigate whether engagement in mindfulness meditation by academic staff at the University of South Australia (UniSA) can contribute to an increase in affective teaching and learning, improved academic well-being and student learning. The following research questions were addressed:

1) Can mindfulness meditation increase awareness and the ability to teach in the affective domain among academic staff?

2) Does mindfulness meditation increase psychological well-being among academic staff?

3) What is the value of affective learning and teaching for staff and students?

4) How can an emphasis on affective learning improve student learning outcomes?

The first two questions will be discussed in this paper: the last two questions have been reported elsewhere (Evans, Ziaian, Sawyer, & Gillham, 2013) .

2. Literature Review

2.1. Affective Teaching and Learning

For many years the enhancement and measurement of cognitive abilities have been used as the basis for educational methods (Birbeck & André, 2009) , however a new culture in education has emerged with a change away from solely cognitive teaching (Napoli, 2004) , due to social change within communities (Morris, 2009; Napoli, 2004) , and the impact on the educator and educational institutions has been immense. The knowledge required of educators to understand, address and support the emotional challenges has grown considerably. These feelings and emotions are often referred to as the affective domain (Bolin, Khramtsova, & Saarnio, 2005; Holt & Hannon, 2006) and research to determine the significance of affective learning and teaching has provided insight into the practical implications for learning outcomes in various fields (Craig, 2011; Holland, 2006) .

This research indicated that attitude, interest, values and the development of appreciation affect the personal learning experience. Recognition of affective motives enhances self-esteem and it was found that student achi- evement levels are a consequence of self-esteem and social motives like praise and support (Walberg, 1984 as cited in McNabb & Mills 1995 ). A “feel good experience” is vital to the learning process in order to provide a positive cognitive end-result and maximise learning (Birbeck & Andre, 2009; Sonnier, 1989; Zhang & Lu, 2009) . Likewise, what we know will influence what we feel, and affective teaching can therefore be used to optimize the cognitive domain and improve learning outcomes.

A combination of support in both the affective and cognitive domains is viewed as the most successful teaching method (Huk & Ludwig, 2009; Tait-McCutcheon, 2008; Zhang & Lu, 2009) . Empathy, responsibility, affective responses and resultant attitude can be transformed when the cognitive and affective domains are interrelated (Littledyke, 2008; Moore & Malinowsky, 2008; Thompson & Mintzes, 2002) , thus further study on the affective and cognitive experiences is of critical importance (Littledyke, 2008; Thompson & Mintzes, 2002) .

2.2. Mindfulness, Contemplative Practices and Mental Well-Being

The benefits of mindfulness and the use of meditative practices to obtain well-being are well documented (Brady, 2007; Hirst, 2003; Lavric & Flere, 2008; Manocha, 2011; Nelson, 2003; Oman, Shapiro, Thoresen, Flinders, Driskill & Plante, 2007; Walach, Buchheld, Buttenmuller, Kleinknecht, & Schmidt, 2006) . Mindfulness meditation is seen as a very valuable instrument to ease and discard the mindless and restless striving that often encompass our daily life and habits, and transform negative impulses into positive impulses (Hyland, 2009; Hyland, 2010) . The practical implications developed through meditation are represented as joy, rest, concentration, curiosity, diligence, equanimity and mindfulness (Brady, 2008) and confirm that the cultivation of mindfulness assists in maintaining alertness, motivation and commitment (Hyland, 2010) .

Although more research is necessary in this field, initial studies have shown that the use of contemplative/ mindfulness practices improves concentration and cognitive flexibility. Conation, attention, cognition and affect should be balanced in order to provide psychological well-being and mindfulness meditation has been found to influence these outcomes (Littledyke, 2008; Moore & Malinowski, 2008) . Some researchers concluded that mindfulness can be developed through cognition, attitude and positive consciousness and that specific developed practical exercises are beneficial to provide motivation and enhance relationships (Brown & Ryan, 2003; Hollis-Walker & Colosimo, 2011; Martin, 2011) .

Researchers generally agree that significant psychological benefits are gained from mindfulness-based interventions and results indicate a reduction in negative elements including stress, anxiety and depression. It is also noted that positive changes in self-esteem occur when meditative practices are used (Coffey, Hartman, & Fredrickson, 2010; Dobkin, 2008; Greeson, 2009; Hollis-Walker & Colosimo, 2011; Hyland, 2009; Ott & Hölzel, 2006) . Structured contemplative practices improve attention, assist in gaining inner-peace, improve awareness and expression, as well as develop compassion which in turn improves mind and body (Burack, 1999; Coffey, Hartman, & Fredrickson, 2010; Greeson, 2009; Manocha, 2011; Ott & Hölzel, 2006) .

2.3. The Value of Mindfulness Meditation in Education and Improvement of Learning Outcomes

Contemplative education as a means to develop the “whole person” enjoys considerable discussion and diverse definitions (Lillard, 2011; Roeser & Peck, 2009) . Roeser and Peck (2009: p. 133) define contemplative practice as “a set of pedagogical practices designed to cultivate the potentials of mindful awareness and volition in an ethical-relational context in which the values of personal growth, learning, moral living, and caring for others are also nurtured”. Self-awareness and the use of contemplative practices within the academic system to cultivate conscious awareness are seen as essential for personal growth, learning and moral development (Craig, 2011; Bai, Scott, & Donald, 2009, Holland, 2006; Roeser & Peck, 2009) . The importance of reflection in education has also been emphasised and the conclusion drawn that several reflective practices can act as “metacognitive attention-training exercises” (Repetti, 2010: p. 13) . The balance achieved between mind and body receives attention in the study by Dolan (2007) and the findings are substantiated by meditation programs delivered at DePaul University, Chicago (Repetti, 2010) . The implication for student development is that the application of mindfulness techniques can assist towards adaptive responses. Various techniques in mindfulness meditation were used in a study conducted by Stew (2008) in a university setting. No prior knowledge of meditation, religious or philosophical connections were necessary to participate in this study which determined the influence on stress levels as well as influence on academic work, clinical practice and personal life. Formal meditation instruction was given as well as informal settings within daily activities. Through “Illuminative Evaluation” (Stew, 2008: p. 136) self-report of awareness, learning strategies, coping abilities, behavioural change and personal well-being could be defined. Mindfulness meditation was seen as beneficial to the development of general awareness, although the main obstacle of time-management to include this practice into the daily routine was observed (Stew, 2008) .

The elements of a well-being curriculum, as well as general meditation techniques are presented in the work by Morris (2009) . Reduced stress, increased awareness and happiness are elements which improve through mindfulness meditation in educational institutions. For instance, mindfulness training supports the educator to deal with the demands and added stress of student numbers, increase their focus, as well as develop attention abilities which assist in reducing information from quantity to quality. These attributes develop creativity, which will subsequently support changes in the classroom as well as improve the personal life of the educator (Napoli, 2004) . Stress management interventions (SMIs) were also researched amongst academic staff by Stefansdottir & Sutherland (2005: p. 321) , calculating communication preferences and behavioral changes using the “Insights System of Personality Types to Increase Awareness”. This study also proved that mindfulness can improve the ability to cope with stress and identify perceived stressors.

The Higher Education College in Massachusetts was the location for research on the impact of meditation in education and the process towards human wholeness and co-existence. Meditative practices in this Community for Integrative Learning and Action (CILA) are aimed at enhancing intuition, insight, creativity, attention and interconnectedness, to name a few (Robinson, 2004) .

Garland and Gaylord (2009) confirm the many positive aspects resulting from mindfulness meditation and the evidence that exists for improvement of the affective domain. Contemplative observation influences intellectual thoughts on areas of critical thinking, insightfulness, self-reflection and ethical awareness. Consciously assisting the application of contemplative competence in education provides students with the chance to cultivate their individual abilities to enhance their learning outcomes (De Souza, O’Higgins-Norman, & Scott, 2009) . Further study is recommended to determine which self-compassion elements and individual influences are present in mindful attitude and what the long-term benefits would be to everyday life (Coffey, Hartman, & Fredrickson, 2010; Hollis-Walker & Colosimo, 2011; Ott & Hölzel, 2006) . From an affective learning perspective, mindfulness meditation helps to temporarily disengage the mind from external stimuli to focus inwardly, immediately increasing awareness of thoughts, feelings and emotions.

While mindfulness meditation is widely used and is recognised as a powerful technique for self-awareness and physiological and psychological well-being, there has been no high quality investigation of the use of this technique to improve awareness of the affective domain. The formulation of an inclusive contemplative practice tailored for educational purposes remains a relevant topic of investigation. Although the studies reported here were usually conducted in academic settings and benefits for the educator have been noted, measurement was usually conducted and reported in terms of the advantages for students. The practical implications and benefits for academic staff require further research. This project will provide important data related to the application of mindfulness meditation to teaching and learning to improve psychological well-being among academic staff and improve students learning.

3. Research Method

3.1. Participants

Academic continuing and sessional staff at the Whyalla Campus and Mount Gambier Regional Centre were recruited through snow ball sampling technique to participate in the project. A Participant Information Sheet was provided to staff and outlined the aim of the study, gave details of the structure of the project and the research team, and invited participation in the study. The information sheet also described the study’s requirements of participants, advised that participation was voluntary and that staff were under no obligation and could withdraw from the project at any stage without consequence. Participants would not be identified in any reports or papers concerning the study, and all information collected as part of the study would be kept in a locked cabinet within the Research Office at the Whyalla Campus for five years and accessed only by the researchers.

3.2. Ethics Statements

With approval from UniSA’s Human Research Ethics Committee, written consent was obtained from the participants before commencement of the project. Participants were also offered the opportunity to receive copies of the major findings of the research.

3.3. Design and Procedure

3.3.1. Initial Workshop

An initial workshop was held prior to the commencement of the academic year at both Whyalla and Mount Gambier sites. A total of 14 staff attended these workshops (Whyalla 9; Mt Gambier 5).

Questionnaire Survey-pretest

At the start of the workshop participants completed a one-page pre-workshop questionnaire based on Stenzel’s (2006) “Rubric for Assessing Learning and Teaching in the Affective Domain” to examine their awareness of affective teaching. The participants also completed the “General Health Questionnaire” (GHQ-12) (Goldberg & Williams, 1988) that measures psychological well-being. In this workshop, participants were introduced to the basic principles and techniques of mindfulness meditation and took part in a meditation exercise as preparation for their daily practice.

3.3.2. Journal Writing

At this stage of the project participants were then required to engage in meditation practice for five minutes twice a day for the length of a study period over 13 weeks, and reflect on their discoveries of the effects of being mindful as opposed to being unmindful. Participants were requested to intentionally engage in deep thinking around the affective domain of learning and document strategies for promoting affective teaching and learning, and to record their experiences with the meditation practice in a diary that had been especially prepared and distributed for this task. For each of the 13 weeks, the diary provided space to record the times of the meditation practice and responses to the following items:

What are some of the positive experiences I have encountered in my meditations this week? What are some of the challenges I have encountered in my meditations this week? What are some of the reflections and feelings that I would like to record at the conclusion of this week? My goal for next week is…

Two compact discs containing guided meditations and information/guidance sheets were also provided to assist the participants in undertaking the practice of mindful meditation.

3.3.3. E-mail Motivation

To maintain motivation, a series of e-mails was sent to participants over the 13 weeks and contained URL links and attachments of published articles and reports.

3.3.4. Telephone Interviews

In addition, an independent Ph.D. student experienced in research techniques conducted a telephone interview with participants during week six. The first telephone interview took an estimated 15 minutes and covered the following questions:

1) How are you going with your meditation practice? Are you keeping up with your practice? Are you on track?

2) Have you anything you could share with us?

3) Are you recording your thoughts and feelings in your meditation journal?

If you have noticed any effects during your meditation practice, please do not forget to record them in your meditation journal on a weekly basis.

4) Do you think you need extra support for your daily meditation? If so, what kind of support do you think you may need?

The telephone interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed.

3.3.5. Second Workshop

The second workshop held at the beginning of the new study period commenced with a detailed overview of the structure of the research project, and then focussed on self-reflection and evaluation of the meditation practices; exploring and identifying key affective learning strategies from the literature; and reflective exercises to develop practical, affective learning strategies applicable to the classes the participants would be teaching in study period five.

A second telephone interview was conducted by the same independent Ph.D. student during October. The questions asked were based on those used in the previous interview, and were also digitally recorded and transcribed.

A final workshop was held mid-December at both Whyalla and Mt Gambier sites. The aim of this workshop was to allow participants to reflect on which aspects of the intervention were useful/not useful in determining their affective teaching and learning strategies and how the intervention had impacted on and been applied to their teaching practices. The workshop presenters also shared information relating to the results extracted from the data collected to date. During the workshop, participants were asked to select what they considered to be the five most important strategies for each of three categories of “Strategies to enhance affective learning and teaching” from material distributed for discussion at the second workshop, and then for each category to rank the selected items from 1 to 5 in order of their priority. For the first category headed “Principles underpinning affective learning/teaching” participants were requested to also put M next to the item if they believed their meditation practice contributed to the development of these areas.

With the permission of the participants, this workshop was also digitally recorded in order to capture all the richness of the discussion.

3.3.6. Questionnaire Survey Post-Test

Participants again completed the Staff Survey based on Stenzel’s (2006) “Rubric for Assessing Learning and Teaching in the Affective Domain” and the GHQ-12 (Goldberg & Williams, 1988) questionnaire that measures psychological well-being, to enable comparison with responses collected at the beginning and end of the project and identification of any changes. The data were collected through survey, individual interviews and group discussion at the workshops, with the data from the interviews, staff survey and the GHQ-12 regarding academic psychological well-being of participating staff at the pre and post intervention program analysed and reported in this paper.

4. Results

Of the 28 eligible staff invited to be involved in the study, 14 participated in the research (Whyalla 9; Mt Gambier 5), giving a participation rate of 50%.

4.1. Interview Results

The responses to the meditation intervention were mixed ranging from non-participation through to the description of profound impact from meditation. Emerging themes are discussed with direct quotes from interview transcripts.

4.1.1. Lack of Time

Some respondents found difficulty finding a suitable time and place for meditation, particularly if they were attempting to meditate at work:

“It’s just been lack of time. All the markings come in and I’ve been away a fair bit. When I’m in the office everybody wants a piece of me.”

4.1.2. Links to Religion

Participants linked meditation to religion or religious practice such as prayer:

“I honestly don’t know, but for me I get a very deep sense of joy, it’s just overwhelming, when I meditate, and I believe that to be the Lord for me. I mean, I don’t want to put that on others. That’s just my experience.”

Mindfulness without meditation, reflection, silence and music.

Several participants discussed the benefits of relaxation, reflection, listening to music or mindfulness without specifically identifying this formally as meditation:

“Well I think in terms of being mindful, I think there are other ways of doing that other than through meditation. I think just being aware of the concept of being mindful of how you might teach is enough, sometimes, to be mindful about that. It’s an awareness, and you consciously think through that without having to meditate.”

4.1.3. Not Helpful

Some respondents found mindfulness meditation practice was counterproductive or of little benefit:

“I feel guilt―you know, now, this is an added thing that the project has given me―on top of all the other guilt that I have in my life I feel this additional guilt for not applying myself well to this.”

4.1.4. Benefits for Teaching

Respondents highlighted the benefits of meditation for teaching:

“As a nurse, I need to be able to critically reflect anyway and I’m teaching my students to do that. I think that by doing it myself, it brings me back in line with what I’m trying to teach the students and let them know the benefits of it and I can actually give them examples of those benefits.” “It allows you really to be where you are at a particular time without your mind wandering off and blocking that potential source of information with your own thoughts.”

4.1.5. Stress Management

The contribution to the management of stress was noted:

“I’m not sure whether it’s that, but yeah, maybe it’s just a certain level of calmness helps see things in a different perspective.”

4.1.6. Life Changing Effects

Some respondents indicated life changing effects from meditation:

“Oh, it’s changed my life. I cannot tell you what journaling, and stilling myself has done for me. It is profound. It is absolutely profound… it’s given me a greater love for people, understanding, and the desire to care for them, and for them to know that life is worth it.”

4.1.7. Clarity

Increased clarity and presence in the moment was reported:

“I find that sometimes in the meditation itself kind of like guidance or an inspiration will come through. Other times it might just be I go off into a peaceful meditation, but it could be later on that day or the next day that suddenly a thought comes and like, ah this would be a good way to be able to approach that problem that helps to solve it peacefully.” “Because what it teaches me, for example, is that when you have an understanding of what meditation is, what it really teaches you is to be able to just empty your mind and allow to flow in information, guidance, whatever you want to call it from sort of another source. But it means that you’re right in that moment. You can use that skill when you’re, for example, with students... So that you can really hear and concentrate on what the other person is saying to you. I find that when I do that, that obviously their words are important but you pick up on so much more than the words of the person. You pick up on their more comprehensive means of communication with you.”

4.2. Survey Results―Affective Teaching

The pre and post intervention survey asked staff to rate their affective teaching skills and the confidence in carrying out these skills. Pre and post intervention data analysis revealed that the median scores were high indicating a fair degree of implementation of these approaches and confidence in carrying out these skills. At the pre intervention stage, the two lower median scores of 3 and 3.5 are 1) feedback about personal implications and 2) identify implications for how to behave personally. For the confidence in carrying out these skills, the two items that stand out with lower medians (M = 3) are “impact of learning on the well-being of others” and “feedback about personal implications”. For the post intervention survey, the data analysis revealed that all medians are 4, indicating a high degree of implementation and confidence.

The degree of difference between implementation and confidence were examined for pre and post intervention. The data were analysed using a paired t-test. The results are shown in Table 1.

As shown in Table 1, the results of the paired samples test reveal that before the intervention none of the items are statistically significant, although it should be noted that given the small sample size, it would be hard to achieve strict statistical significance. However, the following results of the paired samples test are of special note: listening to students (p = 0.96) has a positive mean indicating the confidence is less than the degree it is carried out. In regards to the reflection on personal meaning of what they learned (p = 0.054), the mean is positive indicating that confidence for this item is less than the degree that it is carried out. For question 7 (p = 0.082),

Table 1. Academic staff awareness of affective teaching skills before and after intervention.

the mean is negative indicating that confidence to do this is higher than the degree to which it is carried out. Assessing the degree of difference between implementation and confidence for the post intervention, the results of the paired sample (Table 1) indicate no statistical significance. At this period of time there appears to be little difference between degree of implementation and confidence.

4.3. Survey Results―Psychological Well-Being

Psychological well-being of the academic staff before and after intervention was measured using the GHQ-12 (Goldberg & Williams, 1988) questionnaire. The results of the GHQ scores at the beginning and end of the project were analysed and a comparison of responses were made for the identification of any changes. The questionnaire has 12 items scaled from 1 - 4. The total score range is 12 - 48. A mixed model was set up to analyse this, due to the fact that some participants did not complete both parts (pre and post) and the mixed model avoids the situation where responses would be lost.

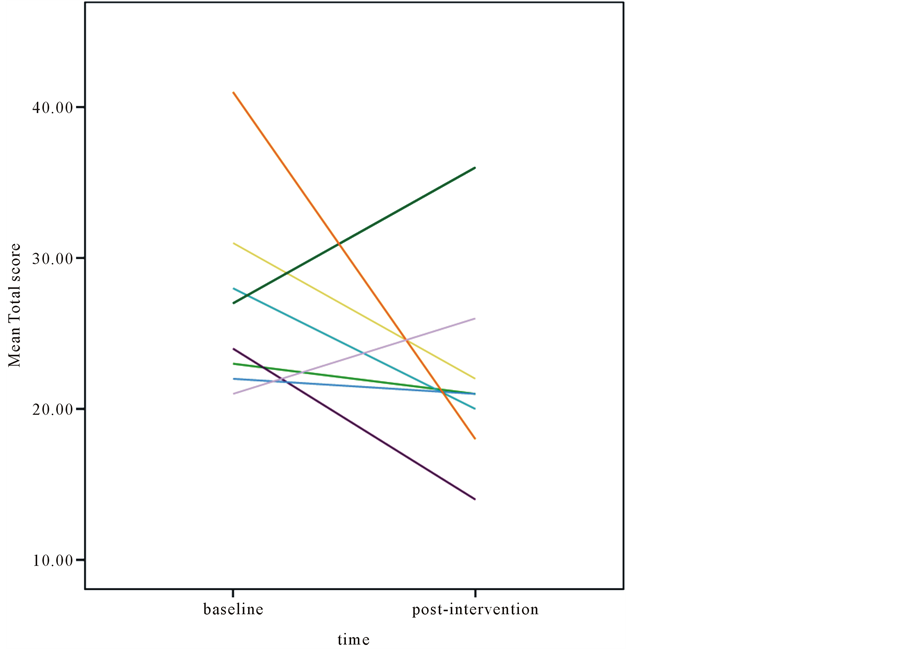

The sum of the scores is used as the outcome variable as advised by Goldberg with lower total scores demonstrating better psychological well-being. As indicated in Figure 1, total scores are decreasing for most participants indicating that the psychological well-being of the academic staff improved over the life of the project.

While the GHQ result is not statistically significant (p = 0.146), the p-score is on the low side rather than the high side. Arithmetically scores show a decrease from pre to post and this is the desirable outcome. The GHQ results for pre and post intervention is of particular note. The pre intervention data were collected in February when academic teaching has not yet commenced and is a less stressful period whereas the post-intervention data were collected in early December, the intense or more stressful period of the academic year.

5. Discussion

The main findings of this pilot study were that the affective learning/meditation workshops improved both confidence and implementation of affective learning strategies while also contributing to improved psychological well-being amongst most participants. Interview data in particular highlighted diverse responses from counterproductive through to “life changing” suggesting mindfulness may be extremely effective for some staff but not

Figure 1. GHQ mean total scores of the participant sat baseline and post meditation intervention. The lines represent each individual participant’s level of psychological distress. The spaghetti plot shows the GHQ total score for each participant at the baseline and after the mindfulness meditation intervention. Scores are decreasing for most subjects.

valued at all by others.

The positive psychological influence of meditation is widely recognized. Brown and Ryan (2003) and Dobkin (2008) conducted studies using the Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS), and confirmed that a relationship exists between mindfulness and development of well-being. However, there has been limited exploration of links between contemplative practice or meditation and awareness and implementation of affective teaching. Stew (2008) and Morris (2009) both report implementation of meditation in education settings with Holland (2004) advocating a learning process involving both student and teacher to provide authentic experiential learning in meditation and self-awareness.This pilot project implemented a unique approach explicitly combining affective learning and meditation interventions, to produce interesting outcomes. In particular participants were encouraged to reflect on affective learning strategies concurrently with meditation, so the affective and meditation strategies mutually reinforced each other.

However, the study was clearly limited by a very small sample.

No prior knowledge of meditation, religious or philosophical connections were set as the exclusion criteria for participation in the study. Therefore those who participated in the study were interested in meditation practices and some had prior exposure to mindfulness meditation which may have biased the sample selection. This prior exposure was varied and was described at different times by participants as prayer, meditation, relaxation and reflection. Therefore it should be noted meditation strategies may vary and individuality, cultural and religious diversity will influence the outcomes (Hassed, Sierpina, & Kreitzer, 2008; Holland, 2004; Palmer & Rodger, 2009; Stefansdottir & Sutherland, 2005) .

In summary, it is clear from this pilot study that the meditation/affective learning workshops were most beneficial for staff receptive to this approach.

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

This study has shown that combining mindfulness meditation with affective learning strategies produced positive change of values and attitudes towards affective teaching.

However, further research is needed to confirm these findings as participants consisted of a small self-select- ing group. Improvement of stress-levels and general psychological well-being due to contemplative practices were evident in the present study. Of particular importance is acknowledging the need for academic staff to increase their own self-awareness of the affective domain and the importance of being mindful of their affective teaching skills for better psychological well-being. The influence of mindfulness meditation on the affective domain is undoubtedly positive, but methods to include more diverse participants should be considered in future research.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge funding support from the University of South Australia for the conduct of this study and the rural campus participants for their contributions to the study.

Cite this paper

TaherehZiaian,JanetSawyer,NinaEvans,DavidGillham, (2015) The Impact of Mindfulness Meditation on Academic Well-Being and Affective Teaching Practices. Creative Education,06,2174-2185. doi: 10.4236/ce.2015.620222

References

- 1. Attwood, R. (2009). Questions of Cost and Usefulness Dog E-Learning. Time Higher Education.

https://www.timeshighereducation.com/news/questions-of-cost-and-usefulness-dog-e-learning/406838.article - 2. Bai, H., Scott, C., & Donald, D. (2009). Contemplative Pedagogy and Revitalization of Teacher Education. Alberta Journal of Educational Research, 55, 319-334.

- 3. Birbeck, D., & Andre, K. (2009). The Affective Domain: Beyond Simply Knowing. Australian Technology Network (ATN) Assessment Conference, 19-20 November 2009, 40-47.

- 4. Bolin, A. U., Khramtsova, I., & Saarnio, D. (2005). Using Student Journals to Stimulate Athentic Learning: Balancing Bloom’s Cognitive and Affective Domains. Teaching of Psychology, 32, 154-159.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s15328023top3203_3 - 5. Brady, R. (2007). Learning to Stop, Stopping to Learn Discovering the Contemplative Dimension in Education. Journal of Transformative Education, 5, 372-394.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1541344607313250 - 6. Brady, R. (2008). Realizing True Education with Mindfulness. Journal of the Sociology of Self-Knowledge, 6, 87-98.

- 7. Brown, K. W., & Ryan, R. M. (2003). The Benefits of Being Present: Mindfulness and its Role in Psychological Well-Being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84, 822-848.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.84.4.822 - 8. Burack, C. (1999). Returning Meditation to Education. Tikkun, 14, 41-46.

- 9. Coffey, K. A., Hartman, M., & Fredrickson, B. L. (2010). Deconstructing Mindfulness and Constructing Mental Health: Understanding Mindfulness and Its Mechanisms of Action. Mindfulness, 1, 235-253.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12671-010-0033-2 - 10. Craig, B. (2011). Contemplative Practice in Higher Education: An Assessment of the Contemplative Practice Fellowship Program, 1997-2009 (pp. 1-124). Northampton, MA: Center for Contemplative Mind in Society.

- 11. De Souza, M., O’Higgins-Norman, F. J., & Scott, D. (2009). International Handbook of Education for Spirituality, Care and Wellbeing. London: Science and Business Media.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-9018-9 - 12. Dobkin, P. L. (2008). Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction: What Processes Are at Work? Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice, 14, 8-16.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ctcp.2007.09.004 - 13. Dolan, M. (2007). A New Transformation in Higher Education: Benefits of Yoga and Meditation. International Forum of Teaching and Studies, 3, 31-36, 70.

- 14. Evans, N., Ziaian, T., Sawyer, J., & Gillham, D. (2013). Affective Learning in Higher Education: A Regional Perspective. Australian and International Journal of Rural Education, 23, 23-41.

- 15. Garland, E., & Gaylord, S. (2009). Envisioning a Future Contemplative Science of Mindfulness: Fruitful Methods and New Content for the Next Wave of Research. Complementary Health Practice Review, 14, 3-9.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1533210109333718 - 16. Goldberg, D., & Williams, P. (1988). A User’s Guide to the HHQ. Windsor: NFER-Nelson.

- 17. Greeson, J. M. (2009). Mindfulness Research Update: 2008. Complementary Health Practice Review, 14, 10-18.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1533210108329862 - 18. Hassed, C., Sierpina, V. S., & Kreitzer, M. J. (2008). The Health Enhancement Program at Monash University Medical School. Explore, 4, 397-394.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.explore.2008.09.008 - 19. Hirst, I. S. (2003). Perspectives of Mindfulness. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 10, 359-366.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2850.2003.00610.x - 20. Holland, D. (2004). Integrating Mindfulness Meditation and Somatic Awareness into a Public Educational Setting. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 44, 468-484.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0022167804266100 - 21. Holland, D. (2006). Contemplative Education in Unexpected Places: Teaching Mindfulness in Arkansas and Austria. Teachers College Record, 108, 1842-1861.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9620.2006.00764.x - 22. Hollis-Walker, L. H., & Colosimo, K. (2011). Mindfulness, Self-Compassion, and Happiness in Non-Meditators: A Theoretical and Empirical Examination. Personality and Individual Differences, 50, 222-227.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2010.09.033 - 23. Holt, B. J., & Hannon, J. C. (2006). Teaching-Learning in the Affective Domain. Strategies, 20, 11-13.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08924562.2006.10590695 - 24. Huk, T., & Ludwig, S. (2009). Combining Cognitive and Affective Support in Order to Promote Learning. Learning and Instruction, 19, 495-505.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2008.09.001 - 25. Hyland, T. (2009). Mindfulness and the Therapeutic Function of Education. Journal of Philosophy of Education, 43, 119-131.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9752.2008.00668.x - 26. Hyland, T. (2010). Mindfulness, Adult Learning and Therapeutic Education: Integrating the Cognitive and Affective Domains of Learning. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 29, 517-532.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02601370.2010.512792 - 27. Lavric, M., & Flere, S. (2008). The Role of Culture in the Relationship between Religiosity and Psychological Well-Being. Journal of Religion and Health, 47, 164-175.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10943-008-9168-z - 28. Light, P. (2006). The Need to Engage Our Students. TRACE Teaching Matters, 20.

- 29. Lillard, A. S. (2011). Mindfulness Practices in Education: Montessori’s Approach. Mindfulness, 2, 1-12.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12671-011-0045-6 - 30. Littledyke, M. (2008). Science Education for Environmental Awareness: Approaches to Integrating Cognitive and Affective Domains. Environmental Education Research, 14, 1-17.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13504620701843301 - 31. Manocha, R. (2011). Meditation, Mindfulness and Mind-Emptiness. Acta Europsychiatrica, 23, 46-47.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1601-5215.2010.00519.x - 32. Martin, B. (2011). On Being a Happy Academic. Australian Universities’ Review, 53, 50-56.

- 33. McInnis, C. (2003). New Realities of the Student Experience: How Should Universities Respond? 25th Annual Conference, European Association for Institutional Research, Limerick, 24-27 August 2003.

- 34. McNabb, J. G., & Mills, R. (1995). Tech Prep and the Development of Personal Qualities: Defining the Affective Domain. Education, 115, 589-592.

- 35. Moore, A., & Malinowski, P. (2008). Meditation, Mindfulness and Cognitive Flexibility. Consciousness and Cognition, 18, 176-186.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2008.12.008 - 36. Morris, I. (2009). Teaching Happiness and Well-Being in Schools: Learning to Ride Elephants. London: Continuum International Publishing Group.

- 37. Napoli, M. (2004). Mindfulness Training for Teachers: A Pilot Program. Complementary Health Practice Review, 9, 31-34.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1076167503253435 - 38. Nelson, D. (2003). Hopi Shooting Starts: Mindfulness in Education. The International Journal of Humanities and Peace, 19, 59-60.

- 39. Oman, D., Shapiro, S. L., Thoresen, C. E., Flinders, T., Driskill, J. D., & Plante, T. G. (2007). Learning from Spiritual Models and Meditation: A Randomized Evaluation of a College Course. Pastoral Psychology, 54, 473-493.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11089-006-0062-x - 40. Ott, U., & Hölzel, B. (2006). Relationships between Meditation Depth, Absorption, Meditation Practice and Mindfulness: A Latent Variable Approach. The Journal of Transpersonal Psychology, 38, 179-199.

- 41. Palmer, A., & Rodger, S. (2009). Mindfulness, Stress, and Coping among University Students. Canadian Journal of Counselling, 43, 198-212.

- 42. Repetti, R. (2010). The Case for a Contemplative Philosophy of Education. New Directions for Community Colleges, 151, 5-15.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/cc.411 - 43. Robinson, P. (2004). Meditation: Its Role in Transformative Learning and in the Fostering of an Integrative Vision for Higher Education. Journal of Transformative Education, 2, 107-119.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1541344603262317 - 44. Roeser, R. W., & Peck, S. C. (2009). An Education in Awareness: Self, Motivational and Self-Regulated Learning in Contemplative Perspective. Educational Psychologist, 44, 119-136.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00461520902832376 - 45. Sonnier, I. L. (1989). Affective Education: Methods and Techniques. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Educational Technology Publications.

- 46. Stefansdottir, S. I., & Sutherland, V. J. (2005). Preference Awareness Education: Stress Management Training for Academic Staff. Stress and Health, 21, 311-323.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/smi.1071 - 47. Stenzel, E. J. (2006). A Rubric for Assessing in the Affective Domain for Retention Purposes. Assessment Update, 18, 9-11.

- 48. Stew, G. (2008). Mindfulness and Post Graduate Student Learning. In H. V. Knudsen (Ed.), Secondary Education Issues and Challenges. New York: Nova Science Publishers.

- 49. Tait-McCutcheon, S. L. (2008). Self-Efficacy in Mathematics: Affective, Cognitive, and Conative Domains of Functioning. Proceedings of the 31st Annual Conference of the Mathematics Education Research Group of Australasia, Brisbane, 28 June-1 July 2008, 507-513.

- 50. Thompson, T. L., & Mintzes, J. J. (2002). Cognitive Structure and the Affective Domain: On Knowing and Feeling in Biology. International Journal of Science Education, 24, 645-660.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09500690110110115 - 51. Walach, H., Buchheld, N., Buttenmüller, V., Kleinknecht, N., & Schmidt, S. (2006). Measuring Mindfulness—The Freiburg Mindfulness Inventory (FMI). Personality and Individual Differences, 40, 1543-1555.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2005.11.025 - 52. Zhang, W., & Lu, J. (2009). The Practice of Affective Teaching: A View from Brain Science. International Journal of Psychological Studies, 1, 35-41.

http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/ijps.v1n1p35