American Journal of Industrial and Business Management, 2013, 3, 746-753 Published Online December 2013 (http://www.scirp.org/journal/ajibm) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ajibm.2013.38085 Open Access AJIBM Entrepreneurship Motivation: Tunisian Case Jamel Choukir1, Mouna Baccour Hentati2 1Business Administration Department, Al-Imam University, Riyadh, KSA; 2École Supérieure de Commerce de Sfax, Sfax, Tunisia. Email: jchoukir@yahoo.ca, mouna_baccour_hentati@laposte.net Received October 31st, 2013; revised November 30th, 2013; accepted December 7th, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Jamel Choukir, Mouna Baccour Hentati. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. In accordance of the Creative Commons Attribution License all Copyrights © 2013 are reserved for SCIRP and the owner of the intellectual property Jamel Choukir, Mouna Baccour Hentati. All Copyright © 2013 are guarded by law and by SCIRP as a guardian. ABSTRACT The entrepreneurship option was launched in Tunisia nearly one decade ago. The firm creation process seemed to be initiated especially to absorb the increasing number of undergraduates and graduates. Therefore, the main aim of the present research is to highlight the entrepreneurship motivation as a social issue and to understand the link existing be- tween motivator factors and economic and social success. Hence, a survey by questionnaire was conducted based on 100 respondents representing Tunisian entrepreneurs. The results revealed that there are links between motivator factors and entrepreneurship as well as some ties between entrepreneurship, motivator factors and the antecedents, especially concerning gender, age and family background. The results have shown some differences existing between male and female entrepreneurs. Male entrepreneurs’ motivator factors are in the same importance with push and pull ones. Fe- male entrepreneurs’ motivator factors are rather emotional. These results are statistically significance. Thus, the finding would be useful for the stakeholders to understand the entrepreneurship dynamic. Keywords: Motivation; Entrepreneurship; Emotion; Gender 1. Introduction Several studies have examined the women’s moti- vation to become entrepreneurs [1-4]. Some highlighted psychological reasons (personality), while others pointed sociological (constraints, incentives) ones. Reflecting these different attitudes point of view emphasis, a key point of debate emerges concerning the different types of motivator factors such as “pulled”, “pushed”, intrinsic, extrinsic, mixed. Three groups of motivations emerged from research conducted in Canada, the US and Great Britain. It is worth wondering here, which motivator factors seem to be the major determinant for Tunisian’s to become entrepreneurs? How prevalent are these moti- vations operating in Tunisian context? What motivates Tunisian entrepreneurs to start their own business? Our study sample was mixed regarding both women and men. It was composed of 100 entrepreneurs. The respondents are operating business or entrepreneurs for at least 3 years. Literature has shown that the 3-year period represents and reflects that the new company is over- taking the main critical steps. In order to evaluate the situation in the Tunisian context, the analysis of this article draws data to address several questions about the prevalence of various motivations for Tunisian entre- preneurs, the differences between women and men and the links existing between motivation and their economic and social success. The measures used in the analysis are the ability to escape salary carrier and the ability to create own employment and to respond to independence need or balance need. This paper is organized as follows. In the next section, we discuss the entrepreneurship motivation. Section three, we outline the methodology used in this research. Subsequently, we report and discuss the results. Finally, we conclude and suggest new directions for future research. 2. Research Background The most important studies in motivation put a great emphasis on the “pull” and “push” factors. In fact, lack of studies on entrepreneurship motivation in the Tunisian context is not the only reason for exploring and treating this phenomenon. We argue that there are four kinds of  Entrepreneurship Motivation: Tunisian Case 747 motivating factors, some as which are more studied and well known than others. Hence, our literature review which highlights, the emotional side and factors that which are different and specific. Emotions have become one of the most popular areas within organizational scholarship. The integrated frame- work includes different processes explained by previous theorists. The emotional process begins with a focal individual who is exposed to an eliciting stimulus for him/her meaning and experiences a feeling as well as some physiological changes, with downstream conse- quences for attitudes, behaviours and cognitions. Researchers now revealed the infusion of emotion into organizational life [5], with implications on individual or to group, and even firm performance, as well as intricate connections to organizational phenomena as varied as justice, diversity, power, creativity, stress, culture, and others. One question, then, is how to articulate bound- aries because for emotion to mean anything, it can not mean everything. Another question is how to integrate the study of emotion into a coherent whole? Researchers have proposed a wide variety of numerous definitions; the most widely adopted that is depicting that emotions are adaptive responses to the environmental requirements [6-8]. However, [5] argued that there is no tautological formal definition of emotion. Most theorists agree that emotion is a reaction or response to a stimulus and has a range of possible consequences [9]. According to these observations the emotion concept covers many aspects. 3. Conceptual Model and Hypotheses To date, a number of studies have examined different major motivations for becoming entrepreneurs [10]. Some highlight psychological reasons, while others focus on broader social, emotional and economic constraints. According to these different hypotheses, a key point of debate concerns the relative role of that “context, situation” and “individual, personality” plays in deciding to engage in entrepreneurship. We consider that these factors can influence a decision to be entrepreneur, but we consider that they have different affects as far as gender is concerned, i.e . They affect men differently from women. 3.1. Pull or Intrinsic Factors A common finding achieved by numerous studies [11- 13]) is that people are pulled into, or attracted by entre- preneurship for reasons or such factors as the desire for greater independence, financial independence, being one’s own boss, challenge, self-fulfilment, financial op- portunity and self-determination. these studies suggest that these pull factors did not have the sizing response from equally affect as for men and female entrepreneurs in equal bases. The merit of these factors as that the decision behind being an entrepreneur conditioned by personal behaviour. These factors are called intrinsic because they take their source from individual; they are commanded by the personality, the character, the need and the desire which shaped by socialization mechanism. Many pioneer studies [14] considered that only these kind of motivator factors leaded to motivation. In other terms, motivation can just be intrinsic or pull. 3.2. Push or Extrinsic Factors Others studies [10,11,13,15] consider that push factors are relevant for entrepreneurs as a result of job loss, difficulty of finding employment, prolonged joblessness, involuntary layoff. These factors are the major motivat- ing one. In some countries (Canada, US, Britain,), These studies have discovered the existence of a certain link between restructuring and downsizing and rising levels of Small Enterprise/Small Business Organization from the mid-1980 to late 1990. Unemployment rate up followed by the rising of self-employment. This situation creating what some authors called “forced entrepreneurs” “necessity entrepreneurs” (GEM). According to [14] push or extrinsic factors produce stimulation and not motivation. The chance to succeed to be entrepreneur will be more important if the engine is the pull factors; it is an act of an engagement and a commitment. Recent studies carried out in Canada by [1] do not support an “unemployment push” hypothesis. Therefore, we believe that there exist some positive relationship, between motivating factors and entrepre- neurship success rate. 3.3. Work- Family Balance Factors Traditional theories of entrepreneurship neglect the work-family motivation side. Some studies, however, revealed that these factors seem to be especially important for women. In Canada, [16,17] highlights the attraction of flexibility for balancing family and work. [18] also underline the role of family-based motivations, noting that for some women “starting a business may be an adaptive response to the demands of the parent and spouse/partner roles, which are very important to them”. More recent analysis by [1] confirms that the presence and number of children increases women’s likelihood of entering SE/SBO. [4] found that such factor as work- family balance and flexibility to be important motivators for women operating in the Canadian economy in general. 3.4. The Emotional Factors The emotional process begins with intrapersonal pro- Open Access AJIBM  Entrepreneurship Motivation: Tunisian Case 748 cesses when a focal individual is exposed to an eliciting stimulus, registers the stimulus for its meaning, and experiences a state of feeling and some physiological changes, with downstream consequences for attitudes, behaviours and cognitions, as well as facial expressions and other emotionally expressive cues [19]. A stimulus need not be an event that occurs, but can also be a stable feature of the environment that is salient. Indeed, any contact between a person and his environ- ment can become an affective event, particularly when the environment includes other people. Although social interactions tend to be the most salient, economic events and conditions are also important emotional elicitors [20] as are a variety of environmental factors. [21] found that there exist positive elicitors including work-related ac- complishments and overcoming obstacles, personal sup- port, solidarity, and connectedness as well as negative elicitors including inequitable situations focusing largely on non financial compensation, discrimination, both covert and overt conflict and power struggles, violations of norms and trust to the detriment of other individuals or the workplace itself, ideology-based disagreements, actual or potential on-the-job death and humiliation. 3.4.1. Emotional Expression [12] argued that, “From moments of frustration or joy, grief or fear, to an enduring sense of dissatisfaction or commitment… the experience of work is saturated with feeling”. Feelings within organizations are often mixed and ambivalent [22]. [8], distinguished between sponta- neous push factors caused by the feeling and physiology emotional experience versus pull factors caused by social intentions to communicate. Pull factors have largely been investigated under the umbrella of display rules. Push factors include biologically determined affect programs as well as cultural and individual expressive style. Emotion as spontaneous versus deliberate communica- tion has been hotly debated [23]. [8], distinguished be- tween spontaneous push factors caused by the feeling and physiology emotional experience versus pull factors caused by social intentions to communicate. Links between emotional states and behaviors include indirect links to behavior that are mediated by intervene- ing attitudes and cognitions [24]. The domination of other areas within organizational studies, it is important to clarify that not all attitudes, behaviours and cognitions result from the emotional process. The formal definition of an attitude is being a psycho- logical tendency expressed by evaluating a particular entity with some degree of favour or disfavour [24]. These authors argued that emotions and attitudes are still distinct concepts and that attitudes are not merely affect- tive reactions. Job satisfaction was initially defined as a job-related affect [20]. First that job satisfaction is an attitude rather than an emotional experience and second that the evalua- tion of one’s job is not necessarily entirely affective but also has a cognitive component to it as well. [25] found that lower job satisfaction leads to more counternorma- tive behaviours, and that such deviant behaviour is a form of behavioural adaptation in an attempt to restore equity and feelings of empowerment. The term emotion-driven behaviors takes its origin from the Latin word “promotionem”, which suggests to move forward, this reflects the evolutionary role of emo- tion responding to survival challenger with action. Nega- tive emotions may change circumstances for the better in the short and/or long term. For instance, anger can serve to readjust a relationship or interaction [26]. Thus, nega- tive emotions can have positive consequences. In general, the study of emotions within organizations has tended to be more fashionable in the western cul- ture’s, perhaps because the value of emotion seems more counterintuitive to members of individualist versus col- lectivist societies. The field of emotion in organizations is being transformed into a mature hybrid paradigm that stems from a variety of methods and perspectives (Fig- ure 1). 3.4.2. The Framework The literature overview conducted to the presentation of our proposition and framework. Proposition 1: The entrepreneurship motivation depends on four major motivational factors: the pull, the push, the balance and the emotional factors. However, these factors do not act equally and in the same intensity. Their effects depend greatly on the social and demographic profile (gender, age, education level, family background). Proposition 2: Economic and social success: the sustainability of the created enterprise depends largely on the motivator factor nature. We consider that the major economic and social success determinants are mainly the emotional and the pull factors rather than push ones. 4. Methodology The investigation concerning the organizational support was conducted by both a documentary analysis and by a survey as well. 4.1. The Study Sample Our sample of study was composed of a number entre- preneurs from the Sfax, the second most important eco- nomical region in Tunisia, considered by many observers (Deneueil,) as being the most entrepreneurial. These en- repreneurs belong to all sectors such us sanitary, cultural t Open Access AJIBM  Entrepreneurship Motivation: Tunisian Case Open Access AJIBM 749 Emotiona l facto r Entrepreneur profile Balance fa ctor Push factor Pull factor Entrepreneurship Motivation t Eco. and s oc. success Dev. t Figure 1. Research Model. Freedom and great independence (financial and oth- ers); centre, e-marketing, pharmacy, design and advertising, aluminium manufactory, consulting, trade, and multime- dia. All these enterprises were created in different peri- ods as follows: 70% in 2006, 25% in 2007 and 5% in 2008, obtained from three files (C.U.I.E.S., A.P.I., A.N.E.T.I.). Need for commandment; Creativity; Professional success and achievement. Push factors [10,13] explored through these items: Unemployment; Data for this study were gathered by a questionnaire survey managed directly to 100 entrepreneurs in French. The survey contains an assignment explaining the pur- pose of the study. The survey was administered during the third week of March, 2010. We carried out this survey directly on our own with no intermediary, those in some special cases, we mobilized our social capital; it means our colleagues, friends and students. Among the 100 surveys, 85 were completed. However, only 45 usable surveys were retained for data analysis, thus, providing a response rate of 45%. Job loss; Less job; Less appropriate job; Governmental incentives; this item did not treated in literature, but we considered important in Tunisian context. Balance factors [4,15,27] explored through these items: Job-family balance; Work at home (Flexible working hours); Share time between work and family; Emotional factors Emotional factors [5,12,21,24,28] explored through these items: 4.2. Survey Structure Work commitment; We have defined four major dimensions: the antecedents, motivator factors, entrepreneurship motivation and eco- nomic and social success. Each dimension explored ac- cording to certain items. Most of the responses (19/27) anchored in seven-point scales. Individuals asked to in- dicate the extent of agreement or disagreement on a seven- point Likert-type scale ranging from (strongly disagree) to (strongly agree). Solidarity and networking need; Family and personal supports; Discrimination; Job humiliation; Emotional experiences: fear, anger, anxiety, revenge on. 4.2.3. Economic and Social Success Economic and social success explored through these items: 4.2.1. The Antecedents Survival and sustainable project (more than three years); The antecedents concern the following variables: age, gender and education level as well as family background. Ability to escape from unemployment; Be able to be entrepreneur (job alternative). 4.2.2. The Motivator Factors According to our model research (Figure 1), we identi- fied four motivational factors. 5. Data Analysis Pull factors [11] explored through these items: As a first step, we tend to generate the descriptive analy-  Entrepreneurship Motivation: Tunisian Case 750 sis in terms of frequencies and profile (Table 1). As for the second construct (Push factors), we ob- tained one factor (45.926%) with KMO = 0.513 and α of Crombach = 0.6988. Concerning the third construct (balance factors), we obtained one factor (54.707%) with KMO = 0.6, in fact the unidimensionality aspect has been respected and α of Crombach = 0.2147 (unacceptable) but 0.7226 if the first item is deleted. Finally, concerning emotional factors; the reduction analysis factor generates one factor (63.38%) and con- cerning the second construct, we obtained one factor (53.740%) with KMO = 0.788 and α of Crombach = 0.7010. We proceeded ultimately by a linear regression with the aim explaining entrepreneurship motivation through motivational factors through the integration of some antecedents (socio-demographic variables). 6. Findings and Discussion Our results can be summarized as follows: the PCA re- sults allowed us to convert the items into factors. On ap- plying the linear regression (ANOVA) we obtained the following model, research equation below, after testing the non-multicolinearity of the motivator factors. 123 4 YCa F1aF2aF3aF4 where ai represent the coefficients of linear regression equation. Concerning the global model, we obtained significance results as following an R squared = 0.3 with an F of Fisher1 =4.324 › 2 and the T of Student for each coeffi- cient ai (that are the output of SPSS 11.0). Thus, the de- tails of the equation are the following (Table 2). Table 1. The descriptive analysis. Characteristics Modalities Gender Male 70% Female 30% Age 20 to 25 years 15.2% 26 to 30 43.5% 31 to 40 years 34.8% More 40 years 6.5% Parent in business No 32.6% *Yes 67.4% Level Secondary 13% University 87% *The family member’s in business are generally the father, the brother, the husband, the uncle and the cousin. In a second step, we proceeded by some tests such as the fiability analysis (α of Crombach) and unidimensionality analysis (factor reduction analysis with varimax rotation), to measure the scale pertinence. We have to obtain a fiability score superior to 0.6 [15]. This test allowed as the respecting of the most important condition for data treatment. Concerning the first construct we obtained (Pull factors), one factor (55,288%), with KMO = 0.694 respecting the one-dimensional of the selected measures and α of Crombach = 0.7150. 6.1. Factors Affecting Attitudes toward Entrepreneurship Results on entrepreneurship consequences are interesting; the explanation power showed the following the hierar- chical order, from the most important to the last impor- tant factor: the pull, the emotional, the push and finally the balance. 6.2. Results on Pull Factor These factors explained the entrepreneurship motivation with a coefficient β equal to 0.348 (significance student T equal to 2.367). 6.3. Results on Push Factor These factors explained the entrepreneurship motivation with a coefficient β equal to 0.344 (no significance stu- dent T equal to 0.693). 6.4. Results on the Balance Factor These factors explained the entrepreneurship motivation with a coefficient β equal to 0.112 (no significance stu- dent T equal to 0.794). 6.5. Results on the Emotional Factor This factor explained the entrepreneurship motivation with an interested explanation power if the coefficient β equal to 0.262 (significant student T equal to 3.179). According to these results, we noticed that the motivator factors did not act equally; some are most by important, especially the emotional and pull factors. We argued that the explanation lies in the characteristic of the studied population. The emotional constituted a determinant mo- tivator factor. 6.6. Factors Affecting Entrepreneurship Motivation Considering Gender Differences On considering as a filter variable, the linear regression results are summarized in the following two tables: If gender is “male”, the linear regression is as follows (Table 3). However, if gender is “female”, the linear regression became as follows (Table 4). We can understand that the power explanation of the model is better if the gender is female and motivator fac- tors differ with the gender as follow; for men the most important factors that motivate to be entrepreneur are push, pull and balance factors but for the women the factors motivate to be entrepreneur are emotional, bal- ance and pull factors. Cultural and cognitive factors can explain the differ- ences exiting between female and men in entrepreneur- 1Ficher: explicative power of the model T of Student: Degree of sig- nificance of coefficients (ai). Open Access AJIBM  Entrepreneurship Motivation: Tunisian Case Open Access AJIBM 751 Table 2. Linear regression for global model. Coeffi. N. standardized Coefficients standardized Model B Standard error Beta 1 (constant) 1.948 0.094 20.755 0.000 PULL1 0.218 0.092 0.348 2.367 0.023 PUSH1 0.201 0.112 0.344 1.794 0.080 EMOT1 0.262 0.082 0.434 3.179 0.003 BALANCE1 0.112 0.084 0.125 0.693 0.492 Table 3. Linear regression (with male), R squared = 0.2 and F of Fisher = 2. Coeffi. n- standar dised Coeffi. Standar Dised T Significance Model B Standard error Beta 1 (constant) 1.851 0.100 18.536 0.000 PULL1 0.272 0.105 0.344 1.837 0.113 PUSH1 0.295 0.157 0.512 1.881 0.070 EMOT1 0.149 0.107 0.259 1.388 0.176 BALANE1 0.186 0.100 0.473 1.862 0.073 Table 4. Linear regression (with female), R squared = 0.731 and F of Fisher = 5.425. Coeffi. n standar-dised Coeffi Standar-dised T Significance Model B Standard error Beta 1 (constant) 2.319 0.211 11.008 0.000 PULL1 0.270 0.221 0.261 1.224 0.256 PUSH1 7.166E−03 0.158 0.012 0.045 0.965 EMOT1 0.469 0.164 0.591 2.860 0.021 BALANCE1 0.284 0.152 0.441 2.864 0.099 ship motivation. For women, in Tunisian context charac- terized by specific traits, the entrepreneurship represents the most important issue and real alternative to realize themselves. Neither the public sector offering a security nor the private perceived as non ethical could allow women to reach and respond to their needs (balance and flexibility). According to these sociological and psycho- logical considerations, for women to be entrepreneur is conducted by personal behaviour, but the environment constraints operate only as stimulus and incentives. In others words we could not consider women as “forced entrepreneurs”, term used by GEM [29-32], but entre- preneurs by conviction, in others terms the entrepreneur- ship represent very interested alternative for women to realize their selves and their needs. Emotions are no strange from our environment and context; they aren’t entirely individual and biologically but also social. Our emotions are socially shaped. In Tu- nisian context all information revealed that the public sector is saturated in term of employment; the private one is perceived negatively (exploitation, humiliation, and anger). As consequence the entrepreneurship remains for women the most important alternative not especially for economical consideration but for individual and social one, even if the public sector offered more security. For men the situation is not the same, sure that men and women share the same environment but not the same identity and motivation. The roles and the positions are differently conditioned. Cultural group such as women differ in the ways that they deal with entrepreneurship. This Cultural group dif- fer in the schemas and feeling rules that guide their emo- tional registration, for example with female members groups preferring emotional states that emphasize on  Entrepreneurship Motivation: Tunisian Case 752 some values consensus, collaboration. This Cultural group differ in their style or made of expressing particular emo- tions and emotions recognition. There a number of major’s implications for the entre- preneurship stakeholders (banks, relevant authorities,). First, it is obvious that there is a general lack of aware- ness in terms of dealing with the women and men needs in entrepreneurship context. Moreover, as a customer with different motivation to increase the entrepreneurial process performance it is necessary to take in account these difference. Moreover, the entrepreneurial stake- holders still perceive that we deal with entrepreneur women needs and wants in the same way with men needs and wants. Our study revealed that the entrepreneurship motivation is different between men and women. In order to increase the entrepreneurship performance in Tunisian context some adjustments need to be taken. 7. Conclusions In summary, entrepreneurship motivation factor is viewed through many dimensions [33-35]. The results in this paper point to value of the emotional factors in the entre- preneurship process and differences between men and women. The results of this research have implications for both the entrepreneurship stakeholders (banks, relevant authorities) and the academicians (exploration new field, improvement entrepreneurship knowledge in Arab con- text). While, when considering the results of the study, a number of limitations should be noted. The study scope covers only the Sfax region which can represent some biases. It was perceived as a favourable region for entre- preneurship. Thus, it is not really a limitation to gener- alize for the whole Tunisian context. The determinant for being an entrepreneur as the literature showed is not re- lated to regional factors [36-39]. However, it is recom- mended for future studies to make a comparison be- tween different zones in order to increase the capa- bility of generalization. The absence of longitudinal ap- proaches elucidating the entrepreneurship dynamism for men and women in specific context remains problematic. REFERENCES [1] A. B. Arai, “Self-Employment as a Response to the Dou- ble Day for Women and Men in Canada,” The Canadian Review of Sociology and Anthropology, Vol. 37, No. 2, 2000, pp. 125-142. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1755-618X.2000.tb01261.x [2] J.E. Cliff and P. M. Cash, “Women’s Entrepreneurship in Canada: Progress, Puzzles and Priorities,” In: C. G. Brush et al., Growth Oriented Women Entrepreneurs and Their Businesses: A Global Research Perspective, Edward El- gar, London, 2005. [3] E. J. Gatewood, “Entrepreneurial Expectancies,” In: W. B. Carter, K. G. Shaver, N. M. Carter and P. D. Reynolds, Eds., Handbook of Entrepreneurial Dynamics, Sage Pub- lications, Thousand Oaks, 2004, pp. 153-162. [4] K. D. Hughes, “Female Enterprise in the New Economy,” University of Toronto Press, Toronto, 2005. [5] S. Fineman, “Emotions in Organizations,” Sage, Thou- sand Oaks, 1996. [6] P. Ekman, “An Argument for Basic Emotion,” Cognition and Emotion, Vol. 6, No. 3-4, 1992, pp. 169-200. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02699939208411068 [7] P. Ekman, “Universals and Cultural Differences in Facial Expression of Emotions, Nebasaka,” In: J. Cole, Ed., Symposium on Motivation, University Nebaska Press, Lincoln, 1972, pp. 83-207. [8] K. R. Scherer, “Studying the Emotion-Antecedent Ap- praisal Process: An Expert System Approach,” Cognition and Emotion, Vol. 7, No. 3-4, 1993, pp. 325-355. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02699939308409192 [9] N. H. Fridja, “Moods, Emotion Episodes and Emotions,” In: M. Lewis and J. M. Haviland, Eds., Handbook of Emotions, 1988. [10] M. Belcourt, “A Family Portrait of Canada’s Most Suc- cessful Female Entrepreneurs,” Journal of Business Eth- ics, Vol. 9, No. 4-5, 1990, pp. 435-438. [11] D. Lavoie, “Women Entrepreneurs: Building a Stronger Canadian Economy,” Canadian Advisory Council on the Status of Women, Ottawa, 1988. [12] B. E. Ashfortth and R. B. Humphery, “Emotions in Workplace,” Annual Academy of Management Confer- ence, Montreal, 2000. [13] M. Belcourt, “The Family Incubator Model of Female Entrepreneurship,” Journal of Small Business and Entre- preneurship, Vol. 5, No. 3, 1988, pp. 34-44. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08276331.1988.10600299 [14] F. Herzberg, et al., “The Motivation to Work,” John Wiley & Sons, New York, 1959. [15] K. D. Hughes, “Pushed or Pulled? Women’s Entry into Self-Employment and Small Business Ownership,” Gen- der, Work and Organization, Vol. 10, No. 4, 2003, pp. 433-454. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1468-0432.00205 [16] L. Stevenson, “Against All Odds: The Entrepreneurship of Women,” Journal of Small Business Management, Vol. 24, No. 4, 1986, pp. 30-36. [17] L. Stevenson, “Some Methodological Problems Associ- ated with Research Women Entrepreneurs,” Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 9, No. 4-5, 1990, pp. 439-446. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF00380343 [18] H. Lee-Gosselin and J. Grisé, “Are Women Owner- Managers Challenging Our Definitions of Entrepreneur- ship? An In-Depth Survey,” Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 9, No. 4-5, 1990, pp. 423-433. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF00380341 [19] H. A. Elfenbein, “Learning in Emotion Judgments: Train- ing and the Cross-Cultural Understanding of Facial Ex- pressions,” Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, Vol. 30, No. 1, 2006, pp. 21-36. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10919-005-0002-y Open Access AJIBM  Entrepreneurship Motivation: Tunisian Case Open Access AJIBM 753 [20] H. M. Weiss, “Deconstructing Job Satisfaction: Separat- ing Evaluations, Beliefs and Affective Experiences,” Human Resource Management Review, Vol. 12, No. 2, 2002, pp. 173-194. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1053-4822(02)00045-1 [21] C. Boudens, “The Story of Work: A Narrative Analysis of Workforce Emotion,” Organization Studies, Vol. 26, No. 9, 2005, pp. 1285-1306. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0170840605055264 [22] M. Pratt and L. Doucet, “Ambivalent Feelings in Organ- izational Relationships,” In S. Fineman (Ed.). Emotions in organizations, Vol. 2, Sage, London, 2000, pp. 204-226. http://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781446219850.n11 [23] B. Parkinson, et al., “Emotions in social Relations,” Psy- chology Press, New-York Hove, 2005. [24] Eagly and Chaiken, “Attitude Structure and Function,” In D. T. Gilbert, S. T. Fiske and G. Lindzey, Eds., The Hand- book of Social Psychology, 4th Edition, Vol. 1, McGraw- Hill, New York, 1998, pp. 269-322. [25] T. A. Judge, “Insomnia Emotions and Job Satisfaction: Multilevel Study,” Journal of Management, Vol. 32, No. 5, 2006, pp. 622-645. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0149206306289762 [26] M. W. Morris and D. Keltner, “How Emotions Work: An Analysis of the Social Functions of Emotional Expression in Negotiations,” Review of Organizational Behavior, Vol. 22, 2000, pp. 1-50. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0191-3085(00)22002-9 [27] C. G. Brush, “Research on Women Business Owners: Past Trends, a New Perspective and Future Direction,” Entre- preneurship Theory and Practice, Vol. 16, No. 4, 1992, pp. 5-30. [28] S. Fineman, “Emotions in Organizations,” Sage, London, 2000. [29] P. D. Reynolds, M. Hay. and S. M. Camp, “Global Entre- preneurship Monitor,” Executive Report, 1999. [30] M. Minniti, P. Arenius and N. Langowitz, “Global Entre- preneurship Monitor: 2004 Report on Women and Entre- preneurship,” 2005. www.gemconsortium.org [31] C. S. Moore and R. E. Mueller, “The Transition from Paid to Self-Employment in Canada: The Importance of Push Factors,” Applied Economics, Vol. 34, No. 6, 2002, pp. 791-801. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00036840110058473 [32] R. Moore and J. Mueller, “The Growth of Knowledge and the Discursive Gap,” British Journal of Sociology of Edu- cation, Vol. 24, No. 3, 2002, pp. 627-637. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0142569022000038477 [33] Industry Canada, “Shattering the Glass Box? Women En- trepreneurs and the Knowledge Based Economy,” Micro- Economic Monitor, Third Quarter (Special Report), In- dustry Canada, Ottawa, 1998. [34] “Key Small Business Statistics,” Industry Canada, Ottawa, Catalogue No. Iul-9/2005-2E, 2005. [35] D. Keltner and J. Haidt, “Social Functions of Emotions at Four Levels of Analysis,” Cognition and Emotion, Vol. 13, No. 5, 1999, pp. 505-521. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/026999399379168 [36] K. R. Scherer, “Appraisal Theories,” In: T. Dalgleish and M. Power, Eds., Handbook of Cognition and Emotion, Wiley, Chichester, 1999, pp. 637-663. [37] World Economic Forum Report, 2006. [38] Organization for Economic Cooperation and Develop- ment (OECD), “Is There A New Economy?” First Report on the OECD Growth Project, OECD, Paris, 2000. [39] A. Fridlund, “Human Facial Expression. An Evolutionary View,” Academic Press, San Diego, 1994. List of Acronyms API: Agence de Promotion de L’industrie ANETI: Agence Nationale de L’emploi et du Travail Indépendant CUIES: Centre Universitaires d’Insertion et d Es- saimage de Sfax CDA: Centre d’Affaires

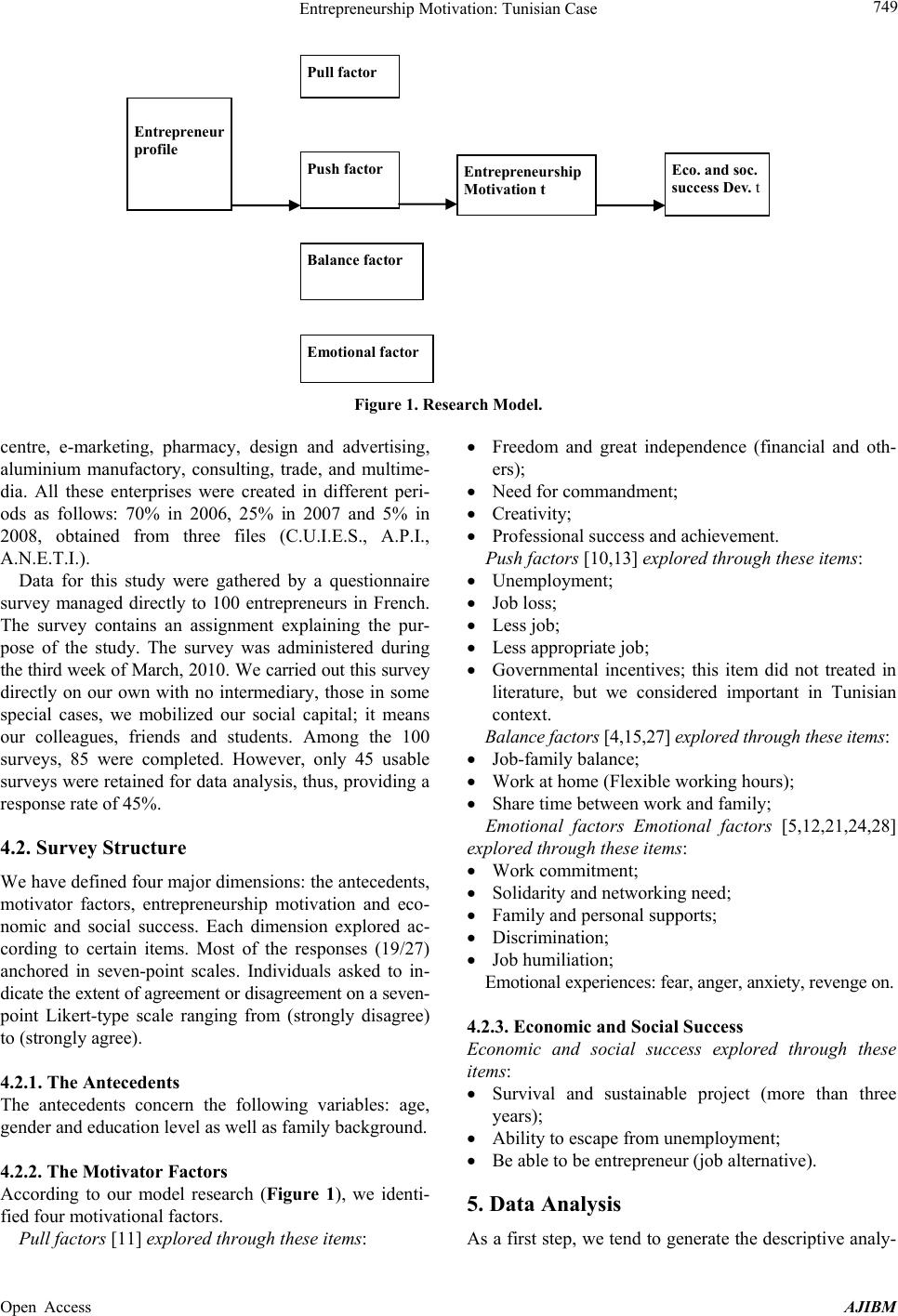

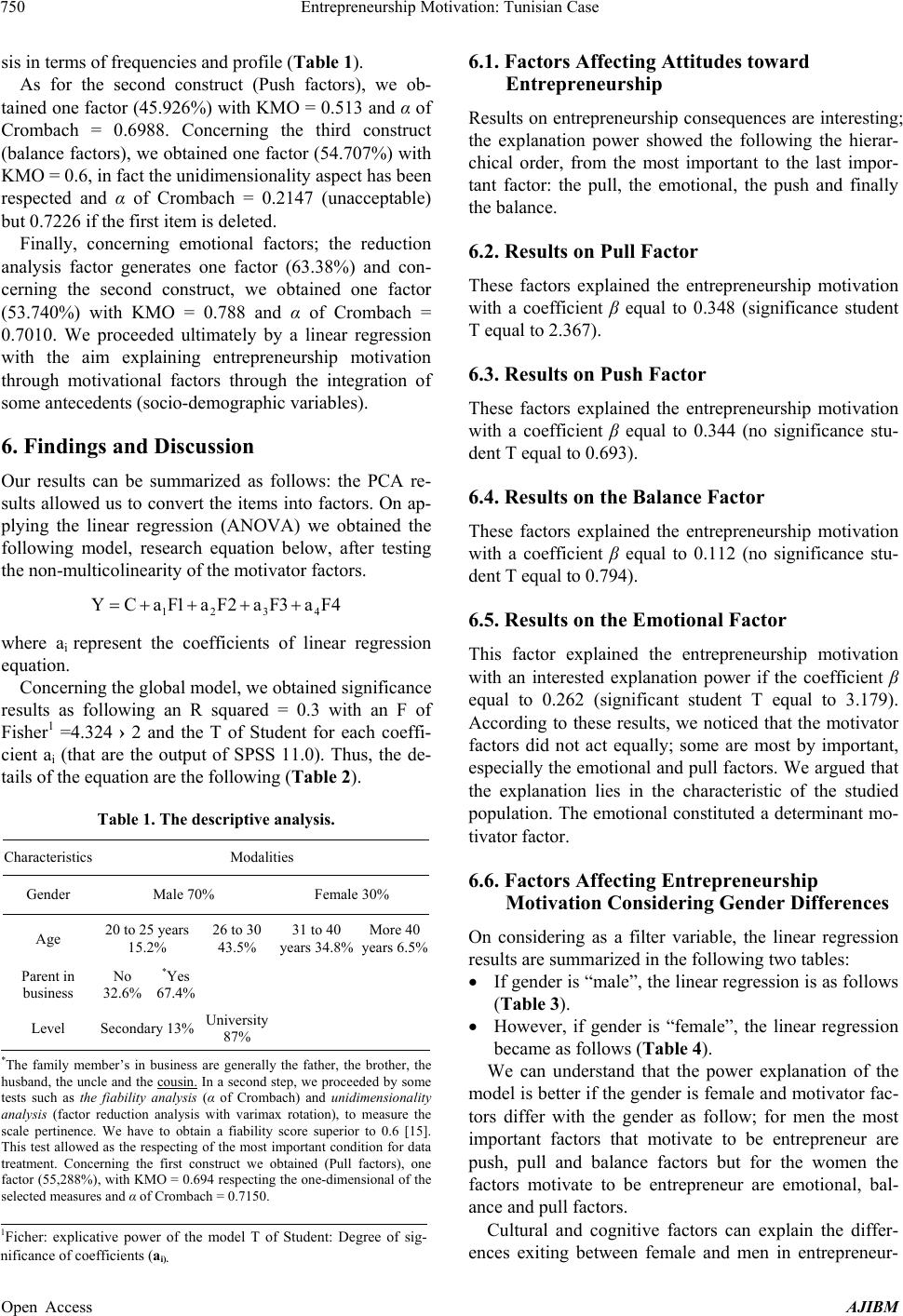

|