Open Journal of Ophthalmology

Vol.06 No.01(2016), Article ID:63456,14 pages

10.4236/ojoph.2016.61004

Ocular Graft versus Host Disease: A Review of Clinical Manifestations, Diagnostic Approaches and Treatment

Sridevi Nair, Murugesan Vanathi*, Anita Ganger, Radhika Tandon

Cornea & Ocular Surface Services, Dr Rajendra Prasad Centre for Ophthalmic Sciences, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, India

Copyright © 2016 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 1 November 2015; accepted 13 February 2016; published 16 February 2016

ABSTRACT

Allogenic haematological stem cell transplantation (allo-SCT) from a human leukocyte antigen (HLA) matched related or unrelated donor is used as a curative therapy for a large number of malignant and non-malignant haematological diseases. The curative effect of allo-SCT is achieved by graft versus leukaemia effect while the downside of the graft versus patient activity is the graft- versus-host-disease (GVHD), a major reason for mortality and morbidity. The search of articles for this review had been accomplished using Ovid, Medline, Embase, Pubmed and was supplemented by retrieving cross references also. Electronic literature search for English language articles with full text access was performed using graft versus host disease, ocular, management, dry eyes as key words. This review has been intended to explicate the classification, pathogenesis, risk factors and management of ocular graft versus host disease.

Keywords:

Stem Cell Transplantation, Ocular, Graft Host Disease

1. Introduction

GVHD is a disease related to allogenic haematological stem cell transplantation. This disease is due to T cell response of donor cells to the proteins of recipient host cells which are genetically defined. These proteins are usually consisting of highly polymorphic HLA which are encoded by the major histocompatibility complex (MHC). HLA class I antigens which includes A, B, C are proteins expressed on nearly all the nucleated cells of the body. Whereas primary expression of class II proteins which includes DR, DQ, DP is mainly on hematopoi- etic cells like dendritic cells, B cells and monocytes except in the conditions of any inflammation and trauma [1] [2] . Even after giving thorough consideration to HLA matching acute GVHD can develop in significant number of patients due to minor histocompatibility antigen (genetic difference which lie outside the HLA loci) [3] [4] . The search of articles for this review had been accomplished using Ovid, Medline, Embase, Pubmed and was supplemented by retrieving cross references also. Electronic literature search for English language articles with full text access was performed using graft versus host disease, ocular, management, dry eyes as key words. This review has been intended to explicate the classification, pathogenesis, risk factors and management of ocular graft versus host disease.

2. Classification of Systemic GVHD

Currently, the classification of acute or chronic GVHD is based on clinical symptoms, unlike earlier time in which time interval was the deciding factor. In earlier times graft-versus-host-disease (GVHD) was divided on the basis of duration after the transplantation. For example GVHD occurring before and at 100 day after the transplantation was referred as acute GVHD (aGVHD), whereas GVHD occurring more than 100 days was termed as chronic GVHD (cGVHD) [5] [6] . Later the two new terms/categories named persistent/recurrent/late- onset were added for cases of aGVHD persisted for >3 months and overlap syndrome in which features of chronic and acute GVHD appear together without any consideration to time limit. Various categories are shown in Table 1 [7] .

3. Systemic GVHD Clinical Features

The incidence of acute and chronic GVHD is reported to be around 40% and 30% - 70% respectively among the HLA-matched patients [8] [9] . According to a study by Vanathi et al. on Indian population the prevalence of chronic systemic GVHD was found to be 33% in post allo-SCT patients [10] . The classical aGVHD presentation includes involvement of mainly three organ systems: skin, gastrointestinal tract and liver. Patients can present with rashes/blisters over skin along with nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, abdominal bloating, blood in stool and loss of appetite in acute stage. Liver involvement is not uncommon, it manifests as jaundice and dark colour urine in acute stage. Whereas in cGVHD additional organs for example-joints, eyes, lungs and genitals also get involved.

3.1. Pathogenesis of Acute GVHD Proceed in 3 Steps

Step 1: Includes activation of antigen-presenting cells (APCs) due to the damage resulted from the allo-SCT conditioning regimen.

Step 2: Includes activation, proliferation, differentiation and migration of donor T cells due to the host histoincompatible antigens presented by the APCs.

Step 3: Includes local tissue injury, inflammation and target tissue destruction due to the cascade of both cellular mediators such as cytotoxic T lymphocytes and natural killer cells [11] .

The chronic GVHD is of autoimmune nature which involves the skin, mouth, GI tract, genitalia, eyes, musculoskeletal system and fibrotic as well as stenotic changes [12] . cGVHD usually starts after aGVHD, though it can start de novo with either involvement of one single organ or widespread in several organs. The most commonly documented sites of involvement in systemic GVHD are skin (75%), mouth (51% - 63%) and liver (29% - 51%) along with associated ocular involvement in 40% - 60% of the patients [1] .

Table 1. Classification of systemic GVHD.

3.2. Pathogenesis of Chronic GVHD

In pathogenesis of cGVHD T cells have been reported to have role whereas detection of auto antibodies support the role of B cells. As cGVHD is of autoimmune nature, it resembles autoimmune diseases like systemic sclerosis [12] .

4. Risk Factors for the Development of Systemic GVHD

The risk factors for the development of acute GVHD as documented in past literature are [13] -[20] :

・ Disparity in HLA;

・ The use of high doses of total body irradiation under conditioning regimens;

・ If female is donor for male recipient and female donor is having history of prior pregnancies or transfusions

・ Lack of prophylaxis for acute GVHD;

・ The recipient’s older age;

・ The peripheral blood stem cells in unrelated donor transplantation have been found associated with both acute and chronic GVHD;

・ Lower incidence of aGVHD is reported in Tacrolimus-based prophylaxis as compared to cyclosporine- based prophylaxis;

・ ABO incompatibility, prior herpes virus exposure, racial predilection and antibiotic gut decontamination are among the other risk factors.

The risk factors for development of cGVHD as documented in past literature are [21] :

・ History of prior aGVHD;

・ Donor’s or recipient’s older age;

・ In transplants where chronic myeloid leukaemia or aplastic anaemia was the primary diagnosis;

・ If female is a donor for male recipient;

・ Incomplete HLA matching for related donors and selection of unrelated donors;

・ If peripheral blood is accepted as a stem cells source;

・ Lack of T-cell depletion.

5. Diagnostic Criteria for Chronic GVHD

According to National Institutes of Health (NIH) working group consensus document, the diagnosis of cGVHD requires distinction from acute GVHD as well as other possible diagnosis. The criterion for diagnosis is either at least one diagnostic clinical sign of cGVHD seen or at least one distinctive manifestation noted which is confirmed by pertinent biopsy/other relevant tests. The diagnosis of cGVHD needs the occurrence of at least one of the diagnostic features in the skin (poikiloderma, lichenoid changes and scleroderma), in gastrointestinal tract (stenosis in the upper or mid-third of the oesophagus or the presence of oesophageal web or strictures), in mouth (restricted mouth opening due to sclerosis , hyperkeratotic patches and lichen-type features ), in genitalia (vaginal scarring or stenosis), bronchiolitis obliterans, and in musculoskeletal system manifestations like fasciitis, joint stiffness, or contractures secondary to sclerosis [7] .

According to NIH consensus though dry eye is a characteristic sign reported in cGVHD, however it itself is not sufficient to make a diagnosis of cGVHD [22] .

6. Ocular GVHD

After allo-SCT, ocular GVHD (oGVHD) develops in 40% - 60% of patients and in already diagnosed GVHD patients, oGVHD develop in 60% - 90% which results in exceedingly severe ocular surface disease [23] -[25] . oGVHD is considered as a poor prognostic sign and develops in about 10% of aGVHD patients [26] [27] . According to study done by Vanathi et al. oGVHD was documented in 30% of post allo-HSCT patients in the Indian population [28] .

The keratoconjunctivitis sicca (KCS) is reported to be the most frequent manifestation of chronic oGVHD (40% - 76% of patients) [29] [30] . In previous literature the patients with skin or mouth involvement are documented to be more prone for the development of oGVHD [31] . oGVHD can occur as an early manifestation of systemic GVHD [32] . KCS can also be initiated by total body irradiation and can also occur due to the immune suppression treatment as it can lead to lacrimal deficiency.

6.1. Pathophysiology of Ocular GVHD

The acute oGVHD is essentially a T-cell-mediated process [27] . Whereas chronic oGVHD is characterized by excessive fibrotic changes and destruction of tubule alveolar glands which ultimately cause damage to ocular surface and result in dry eye [33] . In chronic usually there is increase in number of stromal CD34 β fibroblasts as well as infiltration of T cell in periductal areas [27] . High-risk factors for oGVHD:

・ In patients with skin or mouth involvement [31] .

・ Allo-SCT from unmatched related donors [29] .

6.2. Diagnosis of Ocular GVHD

1) As per NIH consensus, for diagnosing oGVHD [7] the criteria includes either documentation of new ocular sicca with a low mean value of ≤5 mm at 5 minutes in both eyes with Schirmer’s test or documentation of newly onset Keratoconjunctivitis sicca on slit-lamp examination with Schirmer’s test mean values of 6 - 10 mm. If above mentioned two criteria are seen along with the presence of distinctive manifestations in at least one other organ, diagnosis of chronic GVHD is confirmed [7] .

However Schirmer’s score is not sufficient criterion for the diagnosis of chronic oGVHD, as high false positives and negatives are reported if diagnosis is based on Schirmer’s test alone [34] . Other factors like patient’s symptoms, ocular surface staining and tear film dynamics are also important while evaluating such patients of oGVHD [22] .

2) The new diagnostic metrics for chronic oGVHD is defined by the International chronic oGVHD consensus group. As per the consensus group the measurement of following four subjective and objective variables is must in patients of post allogenic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) [22] .

・ Ocular Surface Disease Index (OSDI);

・ Schirmer’s score without putting anaesthetic drops;

・ Staining of corneal surface (CFS);

・ Conjunctival injection.

The variable of conjunctival staining was not taken as parameter due to its high variability in its values. Each variable was scored 0 - 2 or 0 - 3, with a maximum composite score of 11.

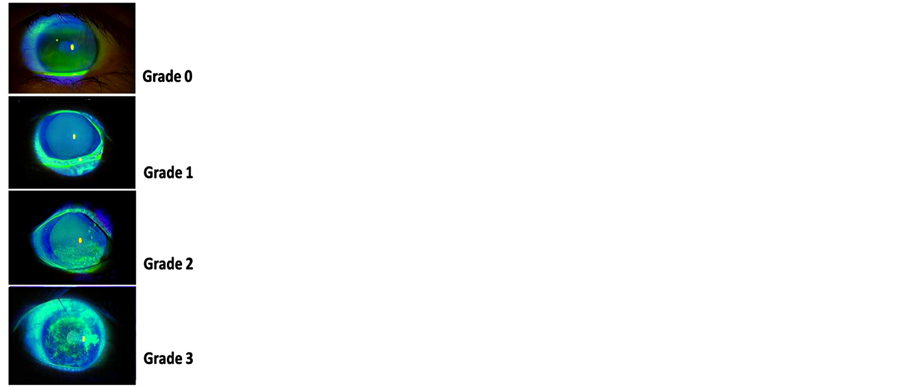

The corneal fluorescein staining scores are marked from 0 to 3 points

・ Grade 0 = If no staining noted;

・ Grade 1 = If minimal staining noted;

・ Grade 2 = If mild/moderate staining noted;

・ Grade 3 = if severe staining noted.

The slit lamp pictures of corneal fluorescein staining used for grading are shown in Figure 1.

The conjunctival hyperaemia score noted in conjunctiva varied from 0 to 2 points

Figure 1. Depicting the corneal fluorescein staining grades.

・ Grade 0 = None;

・ Grade 1 = Mild/moderate;

・ Grade 2 = Severe.

The slit lamp pictures of conjunctival injection used for grading are shown in Figure 2.

A score above 1 point is regarded as abnormal. On the basis of their combined score and after consideration of presence or absence of systemic GVHD, patients are divided in to three diagnostic categories: No, Probable and Definite ocular GVHD.

Based on accumulative scores for each parameter disease severity is assessed by grading patients as none, mild/moderate and severe (Table 2). Based on the total scores assessed and the assessment of presence or absence of systemic GVHD, the diagnosis of oGVHD is made (Table 3).

Severity classification

Total score points are the sum of Schirmer’s test score, CFS score, OSDI Score and Conjunctival injection score.

・ None = 0 - 4;

・ Mild/Moderate = 5 - 8;

・ Severe = 9 ? 11.

3) Grading Scales for Ocular GVHD

A) NIH consensus criteria

In the NIH consensus, the criteria for diagnosing oGVHD is as mentioned in section 6.2.1.

The NIH eye score has a range of 0 - 3 as shown in Table 4.

Figure 2. Conjunctival hyperaemia grading.

Table 2. Severity scale used in grading of chronic ocular GVHD.

Table 3. Diagnosis of chronic ocular GVHD.

Table 4. NIH consensus criteria: Ocular GVHD staging.

B) Japanese dry eye score

The Japanese dry eye criteria [35] for diagnosis is as follows:

1) Presence of symptoms related to dry eye

2) Abnormality of the tear film to be seen by doing Schirmer’s and TBUT test

a) If Schirmer’s1 test values ≤5 mm

b) If Tear film breakup time values ≤5 seconds

3) The damage to the conjunctivocorneal epithelial surface to be noted as follows:

c) With Fluorescein staining, score of ≥3 points

d) With Rose Bengal staining score of ≥3 points

e) With Lissamine Green staining score of ≥3 points

The positive result in at least one of the above tests indicates the conjunctivocorneal epithelial surface damage.

Definite dry eye: Diagnosis of definite dry eye is considered if all three above written criteria are fulfilled.

Probable dry eye: Diagnosis of probable dry eye is considered if either one or two out of 3 above mentioned criteria are fulfilled.

Normal eye: If none of the above written criteria is getting fulfilled.

With this Japanese dry eye scoring system the severity of the dry eye is scored with a range of 0 - 2.

・ Score of 0 = No dry eye if no manifestations/symptoms seen;

・ Score of 1 = Mild dry eye if symptoms present along with Schirmer’s test ≤ 5 mm but fluorescein and rose bengal score are <3 points;

・ Score of 2 = Severe dry eye is diagnosed if symptoms, Schirmer’s test ≤ 5 mm are there along with fluorescein and rose bengal scores are ≥ 3 points.

C) DEWS 2007 score

In DEWS 2007 classification scores of 0 - 4 are given which are determined by evaluating 9 parameters including symptoms of dry eyes, scoring on Schirmer’s test, tear film breakup time, and other abnormalities noted in the conjunctiva, cornea, tear, lid, and meibomian glands [36] .

0 = No dry eye,

1 = Mild dry eye,

2 = Moderate dry eye,

3 = Severe dry eye,

4 = Very severe dry.

6.3. Clinical Features of oGVHD

The oGVHD disease includes wide range of clinical manifestations which affects almost all layers of the eye like the lids, lacrimal glands, conjunctiva, cornea, the vitreous and the choroids. The involvement of the posterior segment is less likely [37] [38] .

6.3.1. The Ocular Surface Manifestations in oGVHD

The outcome of both direct or an indirect conjunctival goblet cell involvement, of lacrimal gland stasis caused by immunosuppression or total body irradiation can give rise to the ocular surface and corneal complications of GVHD [38] . The corneal and conjunctival findings include epithelial thinning, keratinization and squamous metaplasia [39] .

Patients of aGVHD can present with both corneal and conjunctival findings and the severity of their ocular signs generally correlates with the severity of systemic disease.

In aGVHD pseudo membranous conjunctivitis has been documented in 12% - 17% of patients and it is marker of systemic involvement associated with a poor prognosis [40] . The pseudo membranous conjunctivitis can arise after conjunctival hyperaemia associated with epithelial sloughing which subsequently leads to scarring. In severe cases corneal epithelial sloughing presents along with the pseudo membranous changes which occurs in up to one third of patients [40] . Documentation of strong correlation of Dry-eye syndrome or kerato conjunctivitis sicca (KCS) with aGHVD is there in literature [25] .

Chronic GVHD manifestations include new onset of dry, gritty, or painful eyes, excessive tearing, burning sensation, light sensitivity, blurring of vision, cicatricial conjunctivitis, kerato conjunctivitis sicca, and confluent areas of punctate keratopathy [41] .

6.3.2. Dry Eye

In literature dry eye syndrome (DES) is reported as the most frequent complication and documented to be found in 40% to 76% of GVHD patients. The main cause of DES in cGVHD is fibrosis of the acini and ductules proceeded by lymphocytic infiltration of the accessory and major lacrimal glands [29] [30] . However other contributing factors include irradiation, chemotherapy, immunosuppressive therapy, infection and meibomian gland dysfunction [29] .

Though the median time of development of dry eyes is around six months, but it can develop any time between few weeks up to 100 months after transplantation. Most of the patients start experiencing dry eye or foreign body sensation with associated ocular fatigue and discharge which later on progress further to severe dry eye like Sjogren’s syndrome. Burning, stinging, itching, soreness and heaviness sensations in eyelids, and photophobia are among the other symptoms [38] .

6.3.3. Conjunctiva

Conjunctival involvement is found to be rare in aGVHD, though if present, it is a poor prognostic factor and marker for severe systemic involvement. The manifestations of conjunctival involvement vary from mild erythema to pseudo membranous and cicatrizing conjunctivitis similar to Ocular cicatricial pemphigoid.

In aGVHD ulcerative and haemorrhagic conjunctivitis are the more common manifestations, which subsequently progress to scarring and symblepharon formation. These cicatricial changes progress further during chronic phase of GVHD [39] [40] .

Conjunctival Grading in Acute and Chronic GVHD

A) Classification of Conjunctivitis in Acute GVHD [40]

Grade 0―None.

Grade 1―Hyperaemia.

Grade 2―Hyperaemia associated with serosanguinous discharge.

Grade 3―Pseudo membranous conjunctivitis.

Grade 4―Pseudo membranous conjunctivitis with associated corneal epithelial sloughing.

B) Classification of Conjunctivitis in Chronic GVHD [42]

Grade 0―None.

Grade 1―Hyperaemia.

Grade 2―If fibro vascular changes in palpebral conjunctiva seen with or without epithelial sloughing.

Grade 3―If fibro vascular changes in palpebral conjunctiva involve 25% - 75% of total surface area.

Grade 4―If more than 75% of total surface area involved with or without cicatricial entropion.

6.3.4. Corneal Involvement

Corneal involvement is more commonly seen in cGVHD than in aGVHD. In aGVHD features like filamentary keratitis and corneal epithelial keratitis are common. Chronic GVHD mostly shows features of keratoconjunctivitis sicca. Severe dry eyes may present which in turn can cause filamentary keratitis, corneal ulceration, corneal neovascularization, and ultimately corneal perforation if not treated [43] [44] .

6.3.5. Lacrimal Gland Involvement

Lacrimal gland dysfunction is found to be the most common ocular manifestation of ocular GVHD in past literature. In cGVHD disease there is documented tear dysfunction due to infiltration of mononuclear cell into major as well as accessory lacrimal of Kraus and Wolfring [30] .

6.3.6. Cataract

Even though cataract formation is the most common cause of visual acuity loss in these patients, its incidence increase further because of side effects of corticosteroid or total body irradiation therapy [44] .

6.3.7. Other Findings

Anterior uveitis is not very commonly seen during exacerbations of systemic GVHD. It is important to distinguish infectious aetiology or neoplastic masquerade syndrome from non-infectious uveitis [45] [46] .

Posterior segment complications are seen in around 12% of patients. The common vitreoretinal complications seen in GVHD are retinal microvasculopathy including features like intraretinal or vitreous haemorrhage and cotton wool spots [47] .

Central serous chorioretinopathy (CSCR) is not commonly seen in HSCT patients. GVHD itself has been reported to affect the choroidal vasculature leading to choroidal hyper permeability and the development of CSCR.

Association of acute ocular GVHD with posterior scleritis has also been documented in past [48] -[50] . Posterior segment infections such as infectious retinitis due to cytomegalovirus (CMV), herpes simplex virus and varicella zoster virus had also been reported as complications in literature [38] . The manifestation of disc oedema although irreversible is reported to be due to the toxic effects of treating drugs like chemotherapeutic agents for example cyclosporine A and due to coexisting medical conditions [47] .

6.4. Patient Workup

The following parameters should be checked while doing work up of patients suspected of having chronic ocular GVHD [20] .

・ Vision assessment.

・ Slit lamp examination for tear-film break-up time and Schirmer’s test.

・ Intraocular pressure measurement (IOP).

・ Staining the conjunctival surface with lissamine green and cornea with fluorescein dye and then grading of corneal fluorescein staining by using either the National Eye Institute scale or the modified Oxford grading scale.

・ Perform conjunctival or corneal swabs or scrapes for microbiological evaluation in cases of questionable aetiology.

・ Tear film osmolarity and confocal microscopy to help in deciding the treatment modality and follow-up assessment.

・ A dilated fundus examination to rule out posterior segment manifestations of chronic GVHD or cytomegalovirus.

・ Slit lamp examination of Lens, IOP measurement and visual field examination is required to assess any posterior capsular cataract or glaucoma development due to prolonged steroid use or radiation.

・ Symptoms evaluation can be performed by using the Ocular Surface Disease Index (OSDI).

・ Video keratoscope can be used to see difference of higher aberrations of indices in patients with chronic ocular GVHD as compared to normal counterparts.

6.5. GVHD Management Strategies

1) Systemic GVHD prevention and prophylaxis

To prevent GVHD following strategies should be followed:

・ Optimal HLA-matching is must for the prevention of GVHD both MHC class I and II loci between donor and recipient should be matched.

・ The use of Calcineurin inhibitors like cyclosporine and tacrolimus have been reported for the prophylaxis of GVHD. Tacrolimus along with the low doses of methotrexate use is documented for the prophylaxis of acute GVHD. Tacrolimus when used was found to have a lower rate of aGVHD occurrence as compared to cyclosporine [18] .

6.5.1. Acute GVHD Treatment

Systemic immune suppression is the most important aspect while managing GVHD. Steroid therapy, although considered the gold standard for treatment of GVHD due to its antilymphocytic and anti-inflammatory properties, can help in complete remission in less than 50% of patients only and the severe cases more likely don’t respond to steroid therapy alone. Such cases may require a more effective prophylaxis and treatment [51] . 5-year survival rates are also low in the steroid-resistant cases, implying a poorer prognosis. Although MMF, ATG, TNF inhibitors, and other agents are commonly used as second line agent, there is no data to support their use as the same [20] .

6.5.2. Chronic GVHD Treatment

Corticosteroids are the mainstay of therapy for chronic GVHD. Even though they are not totally satisfactory, no other agent has been demonstrated to be better than steroids in the treatment of chronic GVHD in a randomized trial [52] .

The newer treatment modalities which are under trial include:

・ Regulatory T cells modulation using ultra-low dose IL-2 [53] .

・ ECP (Extracorporeal photopheresis) has been shown to be effective in acute steroid refractory GVHD with better long term survival [54] .

・ Imatinib meslylate has shown promising results as an adjunctive therapy in sclera dermatous chronic GVHD [55] .

The most essential step of GVHD management is to avoid infections by giving supportive care in the form of either prevention, prophylaxis and giving treatment. After transplantation during the first year prescription of Acyclovir for viral prophylaxis and trimethoprim sulfamethoxazole or atovaquone for pneumocystis prophylaxis are advised and can be given later on also, if systemic immune suppression is indicated for chronic GVHD [20] .

6.5.3. Ocular GVHD Treatment

The systemic treatments for GVHD help in oGVHD too, but the severity of systemic disease cannot be directly correlated with the ocular manifestations. Therefore increasing the systemic immunosuppression is not the best approach to treat oGVHD. An organ specific approach is more desirable [20] .

The treatment modalities in oGVHD target the following: [56]

・ Ocular surface lubrication and support for the tear film;

・ Control of inflammation;

・ Epithelial and mucosal support;

・ Prevention of tear evaporation.

1) Ocular Surface Lubrication and Support for the Tear Film

Frequent topical lubrication with artificial non-preserved free tears is usually the mainstay of treatment in ocular GVHD with severe aqueous deficiency dry eye [1] . Lubricating medications assist in the dilution of the inflammatory mediators present at the ocular surface.

・ Acetylcysteine (5% - 10%) eye drops can be useful in patients presenting with ocular surface adherent filament [20] .

・ To preserve tears punctal occlusion can be done either with thermal cauterization or with silicone punctual plugs. These when used with autologous serum were found to increase the retention of the same [57] .

Although they haven’t been specially studied in GVHD patients systemic selective muscarinic agonists such as cevimeline or pilocarpine may be used to increase aqueous tear flow [58] .

2) To Control Inflammation

・ Topical steroids

Topical steroids have been shown to be beneficial in aGVHD due to its immunosuppressive action by Kim et al. [59] . Topical steroids have also been shown to be beneficial in cGVHD patients with cicatricial changes without having corneal epithelial defects, infiltrate and stromal thinning [42] .

・ Topical cyclosporine

Topical cyclosporine (CsA) eye drops are useful in patients with chronic ocular GVHD and KCS where other treatment modalities are not successful. Mechanism of action of CsA is to inhibit release of lymphokines from their activated T cells present in the conjunctiva by inhibiting proliferation and production of lymphokines itself. It also increases the conjunctival goblet cell density and decreases the epithelial cell turnover. Topical cyclosporine role in improving corneal fluorescein staining, by improving basal tear secretion in ocular GVHD patients is well documented [60] -[62] .

・ Tacrolimus (FK506)

Tacrolimus (FK506) is a macrolide antibiotic which is similar to CsA in terms of mechanism of action and its pharmacokinetics. Although Systemic tacrolimus has been shown to have a beneficial effect in some cases of ocular GVHD, not enough data is available for the use of topical tacrolimus in these patients. Tam et al have reported successful treatment of a case of oGVHD using topical tacrolimus [63] .

・ Topical Tranilast

Topical tranilast is an anti allergic medication which acts by inhibition of production and release of various ocular inflammatory mediators as well as cytokines. It interferes with migration and the proliferation of vascular medial smooth muscle cells along with inhibition of collagen synthesis and TGF-b induced matrix production. A small group of GVHD patients on treatment with topical tranilast were reported to have shown improvement in reflex tearing and Rose Bengal scores [64] .

3) For Epithelial Support

・ Autologous serum eye drops

In literature autologous serum had been documented to be not only safe but effective modality for the treatment of severe dry eye associated with chronic GVHD. Various factors for example epithelia trophic growth factors, nerve growth factors, cytokines and vitamins present in autologous serum helps in proliferation, differentiation, maturation as well as in maintaining integrity of the both corneal and conjunctival epithelial surfaces [57] .

・ Contact lenses

Contact lenses can be used in moderate to severe dry by stabilising the tear film and also improve the epithelial cells turn over. Significant improvement in dry eye manifestations in terms of both symptoms and visual acuity has been documented in patients with dry eye due to GVHD with the use of silicon hydrogel contact lenses by Russo et al. [65] . Scleral lenses help in relieving the symptoms in dry eye patients by creating a tear filled vault over the cornea [66] .

・ Surgical interventions like limbal stem cell transplantation, amniotic membrane transplantation and penetrating keratoplasty had also been documented as an option to treat severe dry eye. However one should keep in mind the poor prognosis associated with the allografts in these patients is due to poor ocular surface and tear deficiency [67] .

4) For the Prevention of Tear Evaporation

The evaporation of tears may be prevented by maximising the Meibomian gland output by using measures like warm compresses, lid hygiene, topical erythromycin and oral doxycycline therapy. Doxycycline has both antibiotic and anti-inflammatory properties. The latter is due to the inhibition of matrix metalloproteinase and IL-1 activity [68] [69] .

Other treatment modalities that could be used include nutritional supplements such as flax seed oil and fish oil (omega-3 fatty acids), moist chamber glasses and retinoic acid [70] .

5) Use of Systemic Immunosuppression for Ocular GVHD

To avoid unwanted systemic side effects systemic immunosuppression is not suggested in patients with ocular GVHD alone. It is advised in chronic ocular GVHD patients only if, not getting benefit from topical treatment. In terms of ocular surface improvement extracorporeal photopheresis is one another option in chronic GVHD. Imatinib improved the Schirmer’s scores in a small series of patients with chronic GVHD and has shown promise.

7. Conclusion

To summarize, it can be said that transplantation related morbidity has been decreased due to advances in technology used for transplantation these days as well as treatment modality. Though ocular GVHD is contributed mainly by conjunctival and lacrimal gland abnormality but involvement of other ophthalmic structures is also documented especially in chronic GVHD. In chronic ocular surface disorder disease severity can vary from dry eye to severe inflammation and scarring which can lead to sight threatening sequel. In past ocular GVHD was overlooked due to deficiency of exact diagnostic criteria. However, future advances by involving biomarkers for disease identification as well as targeted individual based therapy will lead to focused management protocol and optimal visual outcomes.

Cite this paper

SrideviNair,MurugesanVanathi,AnitaGanger,RadhikaTandon, (2016) Ocular Graft versus Host Disease: A Review of Clinical Manifestations, Diagnostic Approaches and Treatment. Open Journal of Ophthalmology,06,20-33. doi: 10.4236/ojoph.2016.61004

References

- 1. Riemens, A., et al. (2010) Current Insights into Ocular Graft-versus-Host Disease. Current Opinion in Ophthalmology, 21, 485-494.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/ICU.0b013e32833eab64 - 2. Chinen, J. and Buckley, R.H. (2010) Transplantation Immunology: Solid Organ and Bone Marrow. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, 125, 324-335.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2009.11.014 - 3. Bleakley, M.R. (2004) Molecules and Mechanisms of the Graft-Versus Leukaemia Effect. Nature Reviews Cancer, 4, 371-380.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nrc1365 - 4. Goulmy, E., Schipper, R., Pool, J., Blokland, E., et al. (1996) Mismatches of Minor Histocompatibility Antigens between HLA Identical Donors and Recipients and the Development of Graft-Versus Host Disease after Bone Marrow Transplantation. New England Journal of Medicine, 334, 281-285.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199602013340501 - 5. Vigorito, A.C., Campregher, P.V., Storer, B.E., et al. (2009) Evaluation of NIH Consensus Criteria for Classification of Late Acute and Chronic GVHD. Blood, 114, 702-708.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1182/blood-2009-03-208983 - 6. Shulman, H.M., Sullivan, K.M., Weiden, P.L., et al. (1980) Chronic Graft-versus-Hostsyndrome in Men. A Long-Term Clinic Pathologic Study of 20 Seattle Patients. American Journal of Medicine, 69, 204-217.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0002-9343(80)90380-0 - 7. Filipovich, A.H., Weisdorf, D., Pavletic, S., et al. (2005) National Institutes of Health Development Project on Criteria for Clinical Trials in Chronic Graft Versus-Host Disease: I. Diagnosis and Staging Working Group Report. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation, 11, 945-956.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bbmt.2005.09.004 - 8. Balaram, M., Rashid, S., Dana, R., et al. (2005) Chronic Ocular Surface Disease after Allogeneic Bone Marrow Transplantation. The Ocular Surface, 3, 203-211.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1542-0124(12)70207-0 - 9. Ferrara, J.L., Levine, J.E., Reddy, P., Holler, E., et al. (2009) Graft-versus-Host Disease. Lancet, 373, 1550-1561.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60237-3 - 10. Vanathi, M., Kashyap, S., Khan, R., Seth, T., et al. (2014) Ocular GVHD in Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation. European Journal of Ophthalmology, 24, 656-666.

http://dx.doi.org/10.5301/ejo.5000451 - 11. Goker, H., Haznedaroglu, I.C. and Chao, N.J. (2001) Acute Graft versus Host Disease—Pathobiology and Management. Experimental Hematology, 29, 259-277.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0301-472X(00)00677-9 - 12. Shimabukuro-Vornhagen, A., Hallek, M.J., Storb, R.F., von Bergwelt-Baildon, M.S., et al. (2009) The Role of B Cells in the Pathogenesis of Graft-versus-Host Disease. Blood, 114, 4919-4927.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1182/blood-2008-10-161638 - 13. Beatty, P.G., Clift, R.A., Mickelson, E.M., et al. (1985) Marrow Transplantation from Related Donor Other Than HLA-Identical Siblings. The New England Journal of Medicine, 313, 765-771.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJM198509263131301 - 14. Hale, G., Slavin, S., Goldman, J.M., et al. (2002) Alemtuzumab (Campath-1H) for Treatment of Lymphoid Malignancies in the Age of Non Myeloablative Conditioning. Bone Marrow Transplant, 30, 797-804.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/sj.bmt.1703733 - 15. Gale, R.P., Bortin, M.M., van Bekkum, D.W., et al. (1987) Risk Factors for Acute Graft-versus-Host Disease. British Journal of Haematology, 67, 397-406.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2141.1987.tb06160.x - 16. Eapen, M., Logan, B.R., Confer, D.L., et al. (2007) Peripheral Blood Grafts from Unrelated Donors Are Associated with Increased Acute and Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease without Improved Survival. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation, 13, 1461-1468.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bbmt.2007.08.006 - 17. Hahn, T., McCarthy Jr., P.L., Zhang, M.J., et al. (2008) Risk Factors for Acute Graft-versus-Host Disease after Human Leukocyte Antigen-Identical Sibling Transplants for Adults with Leukemia. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 26, 5728-5734.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2008.17.6545 - 18. Nash, R.A., Antin, J.H., Karanes, C., et al. (2000) Phase 3 Study Comparing Methotrexate and Tacrolimus with Methotrexate and Cyclosporine for Prophylaxis of Acute Graft-versus-Host Disease after Marrow Transplantation from Unrelated Donors. Blood, 96, 2062-2068.

- 19. Ratanatharathorn, V., Nash, R.A., Przepiorka, D., et al. (1998) Phase III Study Comparing Methotrexate and Tacrolimus (Prograf, FK506) with Methotrexate and Cyclosporine for Graft-versus-Host Disease Prophy-laxis after HLA-Identical Sibling Bone Marrow Transplantation. Blood, 92, 2303-2314.

- 20. Shikari, H., et al. (2013) Ocular Graft-versus-Host Disease: A Review. Survey of Ophthalmology, 58, 233-251.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.survophthal.2012.08.004 - 21. Higman, M.A. and Vogelsang, G.B. (2004) Chronic Graft versus Host Disease. British Journal of Haematology, 125, 435-454.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2141.2004.04945.x - 22. Ogawa, Y., Kim, S.K., Dana, R., Clayton, J., et al. (2013) International Chronic Ocular Graft-vs.-Host-Disease (GVHD) Consensus Group: Proposed Diagnostic Criteria for Chronic GVHD (Part I). Scientific Reports, 3, 3419.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/srep03419 - 23. Bray, L.C., Carey, P.J. and Proctor, S.J. (1991) Ocular Complications of Bone Marrow Transplantation. British Journal of Ophthalmology, 75, 611-614.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bjo.75.10.611 - 24. Franklin, R.M., Kenyon, K.R., Tutschka, P.J., et al. (1983) Ocular Manifestations of Graft-vs.-Host Disease. Ophthalmology, 90, 4-13.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0161-6420(83)34604-2 - 25. Hirst, L.W., Jabs, D.A., Tutschka, P.J., et al. (1983) The Eye in Bone Marrow Transplantation. I. Clinical Study. Archives of Ophthalmology, 101, 580-584.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archopht.1983.01040010580010 - 26. Holler, E. (2007) Risk Assessment in Haematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation: GVHD Prevention and Treatment. Best Practice & Research Clinical Haematology, 20, 281-294.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.beha.2006.10.001 - 27. Saito, T., Shinagawa, K., Takenaka, K., et al. (2002) Ocular Manifestation of Acute Graft versus Host Disease after Allogeneic Peripheral Blood Stem Cell Transplantation. International Journal of Hematology, 75, 332-334.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF02982052 - 28. Vanathi, M., Khan, R., Kashyap, S., Tandon, R., et al. (2014) Ocular Surface Evaluation in Allogenic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation Patients. European Journal of Ophthalmology, 24, 655-666.

http://dx.doi.org/10.5301/ejo.5000451 - 29. Tabbara, K.F., Al Ghamdi, A., Al Mohareb, F., Ayas, M., et al. (2009) Ocular Findings Following Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation (HSCT). Ophthalmology, 116, 1624-1629.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.04.054 - 30. Tuchocka-Piotrowska, A., Puszczewicz, M., Kolczewska, A. and Majewski, D. (2006) Graft-versus-Host Disease as the Cause of Symptoms Mimicking Sjögren’s Syndrome. Annales Academiae Medicae Stetinensis, 52, 89-93.

- 31. Westeneng, A.C., Hettinga, Y., Lokhorst, H., et al. (2010) Ocular Graft-versus-Host Disease after Allogeneic Stem Cell Transplantation. Cornea, 7, 758-763.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/ico.0b013e3181ca321c - 32. Kim, S.K. (2006) Update on Ocular Graft versus Host Disease. Current Opinion in Ophthalmology, 17, 344-348.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.icu.0000233952.09595.d8 - 33. Ogawa, Y. and Kuwana, M. (2003) Dry Eye as a Major Complication Associated with Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease after Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation. Cornea, 22, 19-27.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00003226-200310001-00004 - 34. Jacob, R., Tran, U., Chan, H., Kassim, A., et al. (2012) Prevalence and Risk Factors Associated with Development of Ocular GVHD Defined by NIH Consensus Criteria. Bone Marrow Transplant, 47, 1470-1473.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/bmt.2012.56 - 35. Shimazaki, J. (2007) Definition and Diagnosis of Dry Eye. Journal of the Eye, 24, 181-184.

- 36. Herrero, V.R. and Peral, A. (2007) The Definition and Classification of Dry Eye Disease: Report of the Definition and Classification Subcommittee of the International Dry Eye Workshop. The Ocular Surface, 5, 75-92.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1542-0124(12)70081-2 - 37. Kim, S.K. (2004) Ocular Graft versus Host Disease. In: Krachmer, J.H., Mannis, E.J. and Holland, E.J., Eds., Cornea, Mosby, St Louis, 879-885.

- 38. Hessen, M. and Akpek, E.K. (2012) Ocular Graft-versus-Host Disease. Current Opinion in Allergy and Clinical Immunology, 12, 540-547.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/aci.0b013e328357b4b9 - 39. Jabs, D.A., Hirst, L.W., Green, W.R., et al. (1983) The Eye in Bone Marrow Transplantation. II. Histopathology. Archives of Ophthalmology, 101, 585-590.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archopht.1983.01040010585011 - 40. Jabs, D.A., Wingard, J., Green, W.R., et al. (1989) The Eye in Bone Marrow Transplantation. III. Conjunctival Graft-vs.-Host Disease. Archives of Ophthalmology, 107, 1343-1348.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archopht.1989.01070020413046 - 41. Townley, J.R., Dana, R. and Jacobs, D.S. (2011) Keratoconjunctivitis Sicca Manifestations in Ocular Graft versus Host Disease: Pathogenesis, Presentation, Prevention, and Treatment. Seminars in Ophthalmology, 26, 251-260.

http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/08820538.2011.588663 - 42. Robinson, M.R., Lee, S.S., Rubin, B.I., et al. (2004) Topical Corticosteroid Therapy for Cicatricial Conjunctivitis Associated with Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease. Bone Marrow Transplant, 33, 1031-1035.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/sj.bmt.1704453 - 43. Yeh, P.T., Hou, Y.C., Lin, W.C., Wang, I.J., et al. (2006) Recurrent Corneal Perforation and Acute Calcareous Corneal Degeneration in Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease. Journal of the Formosan Medical Association, 105, 334-339.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0929-6646(09)60125-X - 44. Allan, E.J., Flowers, M.E., Lin, M.P., Bensinger, R.E., Martin, P.J. and Wu, M.C. (2011) Visual Acuity and Anterior Segment Findings in Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease. Cornea, 30, 1392-1397.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/ICO.0b013e31820ce6d0 - 45. Hettinga, Y.M., Verdonck, L.F., Fijnheer, R., et al. (2007) The Anterior Uveitis: A Manifestation of Graft-versus-Host Disease. Ophthalmology, 114, 794-797.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.07.049 - 46. Wertheim, M. and Rosenbaum, J.T. (2005) The Bilateral Uveitis Manifesting as a Complication of Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease after Allogeneic Bone Marrow Transplantation. Ocular Immunology and Inflammation, 13, 403-404.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09273940490912470 - 47. Coskuncan, N.M., Jabs, D.A., Dunn, J.P., Haller, J.A., et al. (1994) The Eye in Bone Marrow Transplantation. VI. Retinal Complications. Archives of Ophthalmology, 112, 372-379.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archopht.1994.01090150102031 - 48. Cheng, L.L., Kwok, A.K., Wat, N.M., Neoh, E.L., et al. (2002) Graft versus Host Disease Associated Conjunctival Chemosis and Central Serous Chorioretinopathy after Bone Marrow Transplant. American Journal of Ophthalmology, 134, 293-295.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0002-9394(02)01464-2 - 49. Kim, R.Y., Anderlini, P., Naderi, A.A., Rivera, P., et al. (2002) Scleritis as the Initial Clinical Manifestation of Graft-versus-Host Disease after Allogenic Bone Marrow Transplantation. American Journal of Ophthalmology, 133, 843-845. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0002-9394(02)01425-3

- 50. Strouthidis, N.G., Francis, P.J., Stanford, M.R., Graham, E.M., et al. (2003) Posterior Segment Complications of Graft versus Host Disease after Bone Marrow Transplantation. British Journal of Ophthalmology, 87, 1421-1423.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bjo.87.11.1421-a - 51. MacMillan, M.L., Weisdorf, D.J., Wagner, J.E., et al. (2002) Response of 443 Patients to Steroids as Primary Therapy for Acute Graft versus Host Disease: Comparison of Grading Systems. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation, 8, 387-394.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1053/bbmt.2002.v8.pm12171485 - 52. Soiffer, R. (2008) Immune Modulation and Chronic Graft versus Host Disease. Bone Marrow Transplant, 42, 66-69.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/bmt.2008.119 - 53. Koreth, J., Matsuoka, K., Kim, H.T., et al. (2011) Interleukin-2 and Regulatory T Cells in Graft-versus-Host Disease. The New England Journal of Medicine, 365, 2055-2066.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1108188 - 54. Greinix, H.T., Knobler, R.M., Worel, N., et al. (2006) The Effect of Intensified Extracorporeal Photochemotherapy on Long-Term Survival in Patients with Severe Acute Graft-versus-Host Disease. Haematologica, 91, 405-408.

- 55. Magro, L., Catteau, B., Coiteux, V., et al. (2008) Effi-cacy of Imatinib Mesylate in the Treatment of Refractory Sclerodermatous Chronic GVHD. Bone Marrow Transplant, 42, 757-760.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/bmt.2008.252 - 56. Nassiri, N., et al. (2013) Ocular Graft versus Host Disease Following Allogeneic Stem Cell Transplantation: A Review of Current Knowledge and Recommendations. Journal of Ophthalmic and Vision Research, 8, 351-358.

- 57. Ogawa, Y., Okamoto, S., Mori, T., et al. (2003) Autologous Serum Eye Drops for the Treatment of Severe Dry Eye in Patients with Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease. Bone Marrow Transplant, 31, 579-583.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/sj.bmt.1703862 - 58. Couriel, D.R. (2008) An-cillary and Supportive Care in Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease. Best Practice & Research Clinical Haematology, 21, 291-307.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.beha.2008.02.014 - 59. Kim, S.K., Couriel, D., Ghosh, S., et al. (2006) Ocular Graft vs. Host Disease Experience from MD Anderson Cancer Center: Newly Described Clinical Spectrum and New Approach to the Management of Stage III and IV Ocular GVHD. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation, 12, 49-50.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bbmt.2005.11.155 - 60. Kiang, E., Tesavibul, N., Yee, R., et al. (1998) The Use of Topical Cyclosporin A in Ocular Graft versus Host-Disease. Bone Marrow Transplant, 22, 147-151.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/sj.bmt.1701304 - 61. Lelli Jr., G.J., Musch, D.C., Gupta, A., et al. (2006) The Ophthalmic Cyclosporine Use in Ocular GVHD. Cornea, 25, 635-638.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.ico.0000208818.47861.1d - 62. Rao, S.N. and Rao, R.D. (2006) Efficacy of Topical Cyclosporine 0.05% in the Treatment of Dry Eye Associated with Graft versus Host Disease. Cornea, 25, 674-678.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.ico.0000208813.17367.0c - 63. Tam, P.M., Young, A.L., Cheng, L.L. and Lam, P.T. (2010) Topical 0.03% Tacrolimus Ointment in the Management of Ocular Surface Inflammation in Chronic GVHD. Bone Marrow Transplant, 45, 957-958.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/bmt.2009.249 - 64. Ogawa, Y., Dogru, M., Uchino, M., et al. (2010) Topical Tranilast for Treatment of the Early Stage of Mild Dry Eye Associated with Chronic GVHD. Bone Marrow Transplant, 45, 565-569.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/bmt.2009.173 - 65. Russo, P.A., Bouchard, C.S. and Galasso, J.M. (2007) Extended-Wear Silicone Hydrogel Soft Contact Lenses in the Management of Moderate to Severe Dry Eye Signs and Symptoms Secondary to Graft-versus-Host Disease. Eye & Contact Lens, 33, 144-147.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.icl.0000244154.76214.2d - 66. Takahide, K., Parker, P.M., Wu, M., et al. (2007) Use of Fluid-Ventilated, Gas-Permeable Scleral Lens for Management of Severe Keratoconjunctivitis Sicca Secondary to Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation, 13, 1016-1021.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bbmt.2007.05.006 - 67. Heath, J.D., Acheson, J.F. and Schulenburg, W.E. (1993) Penetrating Keratoplasty in Severe Ocular Graft versus Host Disease. British Journal of Ophthalmology, 77, 525-526.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bjo.77.8.525 - 68. Smith, V.A. and Cook, S.D. (2004) Doxycycline—A Role in Ocular Surface Repair. British Journal of Ophthalmology, 88, 619-625.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bjo.2003.025551 - 69. Smith, V.A., Khan-Lim, D., Anderson, L., et al. (2008) Does Orally Administered Doxycycline Reach the Tear Film. British Journal of Ophthalmology, 92, 856-859.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bjo.2007.125989 - 70. Couriel, D., Carpenter, P.A., Cutler, C., Bolanos-Meade, J., et al. (2006) Ancillary Therapy and Supportive Care of Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease: National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Project on Criteria for Clinical Trials in Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease: V. Ancillary Therapy and Supportive Care Working Group Report. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation, 12, 375-396.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bbmt.2006.02.003

NOTES

*Corresponding author.