Open Journal of Modern Linguistics

Vol.09 No.04(2019), Article ID:94772,20 pages

10.4236/ojml.2019.94024

A Functional Analysis of the Prime Suffixes in Igbo Morpho-Syntax

Christiana Ngozi Ikegwuonu1, Martha Chidimma Egenti2

1Department of Linguistics and Igbo, Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu University, Uli, Nigeria

2Department of Linguistics, Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka, Nigeria

Copyright © 2019 by author(s) and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY 4.0).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received: June 14, 2019; Accepted: August 27, 2019; Published: August 30, 2019

ABSTRACT

The Igbo language is one of the languages of the Benue Congo family spoken predominantly in the south-east part of Nigeria. Although, some works have been done on the inflectional and extensional suffixes in the language but no detailed study so far has been done on the prime suffixes in the language. It is on this premise that this paper attempts to examine the functional analysis of the prime suffixes in Igbo morpho-syntax with the aim of identifying primary suffixes that exist in the language, classifying them based on the functions they perform in the verb root where they are attached, explore their morphological structures, syntactic patterns, and semantic behaviours in the constructions. The X-bar theory is the theoretical framework for the study. The data for the study were obtained through the recording of the naturally occurring speeches of the native speakers during discourses, and conversations. The findings reveal that the prime suffixes are overtly morphologically marked on the verbs of the language. They have [V], [CV], [CVCV] or [CVCVCV] syllable structures and can be monosyllabic, disyllabic or trisyllabic in nature. They can perform the following semantic functions on the verbs where they are attached in the syntactic structures respectively: imperative, negative, past tense, progressive aspect, preposition as well as adverbial function. Some vowels of the verb roots do harmonize with the vowels of the prime suffixes while some do not. Again, the tones of these suffixes do change when they are mapped unto the verb roots. We, therefore, recommend that more research works be done in the verbs of the language to enhance its growth and development by applying some of the linguistic theories in order to find out how they operate in the language.

Keywords:

Suffix, Prime, Imperative, Negative Function, Past Tense Marker

1. Introduction

Suffixes are affixes which are attached after the base or root of a verb or word in order to modify, extend, and change the meanings or functions of the verbs or words to which they are attached. They are universal phenomena. They are among the subclasses of affixation which are morphologically marked in human languages. Their number, types and functions are language-specific. In many languages of the world, there exist prime suffixes also known as primary suffixes, secondary suffixes and tertiary suffixes. Each of these suffixes performs different unique functions to indicate different semantic meanings in the verbs or words where they are attached in the syntactic structures of different languages. They are bound morphemes in many languages. Being bound morphemes, entails that they cannot exist independently in the syntactic structures. They must be properly affixed to the appropriate hosts, base or roots. In some languages, the word-classes such as nouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs can take these suffixes to yield other different word-classes as well as other different semantic meanings.

The prime suffixes which are the focus of this paper are the type of suffixes that are affixed immediately after the base or root of a verb or word. Morphologically, in the Igbo language, the prime suffixes are overtly marked only on the verbs of the language. The fact is that in the Igbo language, only the verb category is the category that is capable of inflecting and no other category. The nouns, adjectives adverbs and so on do not inflect at all. The prime suffixes that exist in the language can perform different semantic functions on the verbs where they are affixed in the syntactic structures in order to indicate imperative notions, negation, and tense. This study adopts Green and Igwe (1963) tone marking convention, where all the high tones are left unmarked and the low tones and downstep tone are marked.

2. Background to the Study

Morphologically, suffixation is attested in human languages of the world. It is one of the morphological processes in word formation. According to (Agbedo, 2015) , “suffixation is morphological processes that involves the attachment of an affix usually referred to as suffix, which is often a bound morpheme at the end of a root or stem either to inflects or derive another word. Many scholars have attempted to define suffix in various ways according to each person’s perspective. (Radford, 2004) posits that “a suffix is an affix which attaches to the end of a word”. (Ndimele, 1999) asserts that “the suffix is an affix which occurs after the base or root of a word.” (Haspelmath, 2002) affirms that a suffix follows the base. He gives examples in Russian using the suffix -a as in luk-a (hand). The -a in luk-a (hand) is a suffix. In French, the suffix -able can be added to the verb stems thus: lav + ablelavable (washable). Lav is the stem of the laver (to wash). When the suffix -able is attached to it, the -er ending will be dropped so that the resultant word will be an adjective. Furthermore, the suffix -ateur/atrice when affixed to the verbal stems, the resultant words can be nouns or adjectives. -ateur is used for masculine nouns or adjectives while -atrice is used for feminine and so on.

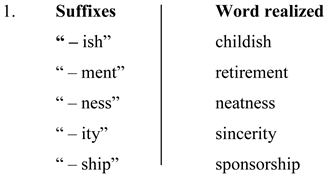

(Nnamdi-Eruchalu, 2007) posits that “suffixes are morphemes which are attached to the back of a root morpheme.” She gives examples in English thus:

From the foregoing, the general consensus is that suffixes are affixes that are attached after the root or base of word. This implies that the position of the suffixes must be after the root or base of a word by attachment. They can be attached to a base or root form to new words. They also modify the meanings of the verbs to which they are attached or affixed.

(Quirk & Greenbawn, 1973) in their view postulate that:

Suffixes frequently alter the word class. They note that suffixes are grouped by the class of word they are perform (for instance, noun suffixes and verb suffixes as well as by the class of the base they are added to like denominal, deadjectival and deverbal.

The view above emphasizes not only on the suffixes being attached after the root, but also on the essence of the suffixes being grouped by the class of word. They perform and the class of base they are attached.

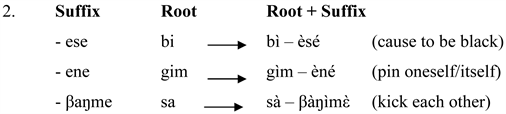

(Kari, 2015) agreeing with the views of (Radford, 2004; Haspelmath, 2002; Nnamdi-Eruchalu, 2007) affirms that a suffix is a kind of affix that attaches after the root. He gives examples with the following suffixes in Degema -ese, -ene and -βaŋmeε which are attached to the root bi (black), gim (pin) and sá (kick) respectively as in:

(Ogbalu, 1972) asserts that “suffixes are words or parts of a word which are affixed after other words thereby forming a single word, examples: che, chègbu, chèpụta, chèkọta, chèmie, chèsì̩rì̩”. He adds that suffixes are responsible for many compound verbs from simple verb roots. That is, they modify the verbs to which they are closely attached, thereby giving them different shades of meaning, examples chepụ̀ta (think out), chemiè (think deeply), jìkọta (bring together), nupụ̀ (push away) and so on.

3. Literature Review

3.1. The Concept of Prime

Etymologically, the word prime originated from Latin word prima (hora) meaning first (hour). In old English, it is prim. It has many other extended meanings. This implies that it can be used to refer to so many things such as the earliest stage, spring or youth, the time when a thing is at its best and so on. The word prime is not only specific to linguistics. It is a word that is used in different fields such as mathematics, music, finance and so on. In these fields, it is used to indicate different notions. For instance, in mathematics, it refers to prime numbers and a prime number is a number that cannot be divided by any number other than itself and one (1).

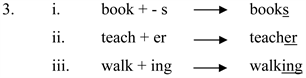

In linguistics, we talk about the prime suffixes and prime suffixes are affixes which are attached immediately after the stem or base or root of a verb or a word. For instance, in English language, these bound morphemes -s, -er and ing are suffixes, which can be attached after the roots or base such as: book, teach and walk respectively as shown in the examples below:

The underlined suffixes above are prime suffixes. They perform different functions in the words where they are attached. In 3(i), the suffix -s functions as a plural marker, in 3(ii), the suffix -er changes the word to become a noun while in 3(iii), the suffix ing makes the word to become a gerund.

3.2. Morphology

Morphology is the level of linguistics analysis that is concerned with the study of the internal structures of words in a language. (Ejele, 1996) posits that morphology studies the internal structures or forms of words; primarily through the use of morpheme concepts as well as the rule by which words are formed. According to (Radford, 1997) , “morphology is the study of how words are formed out of smaller units (traditionally called morphemes”). To (Mathews, 1991) , it is “the branch of grammar that deals with the internal structure of words—the study of the rules governing the formation of words in a language.”

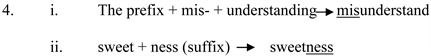

From the above definitions, the general consensus is that morphology concerns itself with the study of formation of words and their internal structures which are made up of smaller units in which their formations are always rule-governed in every language. This means that phonemes of a language are not combined together haphazardly to form words. They must follow the rules governing the formation of word in the language. Consider these examples from English:

In Igbo:

In the above examples, the prefixes are attached to the words in (4i) and (5i) respectively while in (4ii) and (5ii) the suffixes are attached to the words respectively.

3.3. Syntax

Syntax is the branch of linguistics that studies how words are combined to build up phrases, clauses, sentences, and how such sentences can be analyzed or interpreted in the human languages. Most often, the overall meaning of a sentence is the sum total of the meaning of the words in that sentence. (Anozie, 2007) posits that “syntax concerns itself with the way in which words are arranged to show relationships of meaning within and sometimes, between sentences.” To (Finegan, 2008) , “syntax addresses the structure of sentences and their structural functional relationships to one another”. Syntax is the most important aspect of grammar in that languages express meanings through sentences and sentences are composed of words.

From the foregoing, syntax concerns itself with the meaningful arrangement of words in a language in a rule-governed manner to form meaningful sentences. This implies that human languages do not permit the stringing of words together in a haphazard manner. The rules guiding sentence formation in every language must be obeyed to avoid forming ungrammatical and unacceptable sentences. The speaker of a language is obliged to follow the specific rules of his/her language which he/she is internalized. It is that tacit innate knowledge of the rules that we try to capture in the study of syntax. As a result, every human language has regular and specific patterns in which words must be arranged in order to form larger units such as phrases, clauses and sentences in that language. In sum, syntax is the important aspect of grammar in that languages express meanings through sentences and sentences are composed of words.

3.4. Semantics

Semantics is one of the branches of linguistics that studies the meaning of words and sentences in a language. (Radford, 2004) posits that “semantics is the study of linguistic aspects of meaning”. The study of every language without the attachment of meaning is incomplete. Therefore, if after all the morphological, grammatical and syntactic analysis of language and what words and sentences mean cannot be determined, it means that the analysis is not successfully done. So, the study of meaning is very essential in languages. One thing noteworthy is that meaning has diverse impressions according to individual scholar. This has resulted in having many theories of meaning as there are different definitions of meaning. These various theories are geared towards explaining what meaning means. Meaning can be studied at different levels in a language such as at word, phrase, clause, sentence or discourse levels. Whatever utterance one makes is supposed to carry meaning. The meaning of words and sentences is learned and determined by the use to which language is put in communicative situation. Therefore, the study of meaning is very necessary.

3.5. Theoretical Studies

In the morphology of the Igbo language, one cannot talk about suffixation without making reference to the verb system of the language. This implies that Igbo suffixes make constant reference to the verb forms in the language. The fact is that the verb category is very unique in the language because it is characterized with extensive morphological fusions. Hence, (Mbah, 2011) claims that the language has been described as the verb language. This is the view of many Igbo scholars such as (Nwachukwu, 1976, 1983; Anoka, 1983; Emenanjo, 1978) respectively. This is because of the significant roles the verb plays in the grammatical structures of the language. The verb category is highly inflectional than any other word class, hence all types of affixations are rooted in it.

Therefore, suffixation as a sub-class of affixation in Igbo is among the richest and broadest morphological process that makes it feasible for a great number of new words with different significant meanings to be formed or derived from the root or the base. (Green & Igwe, 1963) postulate that suffix “is mostly verb-based”. In addition, they further posit that the frequent use of the suffixes is with the verb. Supporting this view, (Emenanjo, 1978) adds that “suffixes appear only in the verbal slot and as part of the verb stem.” According to (Agbedo, 2015) , “although majority of the suffixes in Igbo language are inflectional, some function as derivational suffixes in which case they act as modifiers.” (Emenanjo, 1978) agrees that “Igbo suffixes modify the meaning of the verb to which they are affixed.” The works of the scholars such as (Ogbalu, 1972; Emenanjo, 1978, 1982, 2015; Onukawa, 1999) among others have built a foundation for the treatment of suffixes in Igbo language respectively. (Green & Igwe, 1963) identify ra (time) suffix, la suffix and ra (non-time) suffix. (Emenanjo, 1978) identifies inflectional suffixes in opposition to (Green & Igwe, 1963) . In (Emenanjo, 1978) words “it is used to be thought that all Igbo suffixes are just simple lexical items that is, elements which do not more than modify the meanings of the verb to which they are affixed”.

Following the syntactic behaviour of all Igbo suffixes in all verbal derivatives and verb forms, (Emenanjo, 1978) in his work divides Igbo suffixes into two classes namely inflectional and extensional suffixes. (Yul-Ifode, 2005) in (Onumajuru, 2008) posits that an inflectional suffix is an affix that is added to the root or base of a word to indicate grammatical relationships (examples, tense, aspect, number). Inflectional affixes give variants of an already existing word without forming new words. They are selected for syntactic reasons. They modify the form of the words or verbs to which they are attached, so that such words fit into the particular syntactic slot. They do not change the cognitive meaning of the hosts. They are used to mark tense, aspects, mood or negation. The inflectional suffixes are -ra/-re, -ro/-kọ/-tara. Emenanjo explains that the suffixes function with inflectional verbal prefixes, auxiliaries and syntactic tone patterns to mark different aspects and verb forms in Igbo language. He identifies the harmonizing open vowel suffixes: -e/ -a, -o / -ọ which are inflectional.

The extensional suffixes are suffixes which function principally as meaning— modifiers, that is, to extend the meaning of the root or stem which they are attached. For a full discussion of this, see (Emenanjo, 1975) . They modify the meaning of their hosts. This implies that they can bring about meaning change in the word to which they are attached. (Onumajuru, 2008) treats extensional suffixes and classified them into eight functional groups within which are a number of subclasses which are referred to as extenders. In Igbo language, extensional suffixes are larger in number than inflectional suffixes. Some examples of the extensional suffixes include:

4. Methodology

The paper adopts a descriptive approach in the analysis of the data. The data used for the study come from both the primary and secondary sources. The primary source was made up of the data drawn largely from the indigenes who are the native speakers of Igbo language that is the L1 speakers through listening and recording of their natural occurring speeches during discourses, conversations, along the streets and market squares. The researcher as an Igbo native speaker also added her intuitive knowledge for some data.

For the secondary source, insights were gained from the library materials, textbooks and journal articles.

5. Theoretical Framework: An Overview

X-bar theory is the theoretical framework adopted in this work. The framework is a system of grammatical analysis that seeks to refine the traditional account of phrase structure. According to the theory, X is a category variable which represents the conventional elements such as noun, verb, adjective, adverb, preposition and so on. (Mmadike, 1998) postulates that X-bar theory specifies how phrases and clauses are built up out of lower constituents. The lower constituents are said to be the head upon which the build-up relies. The central notion of the theory is that each of the major lexical categories (noun, verb, adjective, adverb and preposition) is the head of a structure dominated by a phrasal node of the same category (noun as in noun phrase, verb as in verb phrase, etc). Following this notion, (Finch, 2000) asserts that the basic requirement of this approach is the recognition of intermediate stages in the formation of phrases. In his view, (Radford, 2004) argues that X-bar is used to designated immediate projection that is larger than a word but does not project to even a larger type of expression like phrase. The X-bar (Xˡ) captures the endocentric relationship between the phrase and its head. There is indication here that X-bar is head-based. The head which X-bar emphasizes is related to the phrase. The theory makes uses of bars such as double bars and single bars in the analysis of intermediate categories. It occurs in the configuration below as represented by (Jackendoff, 1977) as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. X-bar configuration with SPEC and COMP.

In the above configuration, X is dominated by Xˡ, which in turn is immediately dominated by Xˡˡ, Xˡ is the immediate head of Xˡˡ and X is the ultimate head of Xˡˡ SPEC is a sister to Xˡ and X is a sister to COMP. In this way, COMP exists in a closer relationship to X than SPEC and SPEC has a closer tie to Xˡ than COMP. SPEC and COMP appear in different structural positions within the phrase. XP is regarded as the maximal category Xˡ, the intermediated category and X is the lexical category. This theory permits considerable economy in the formation of phrases.

6. Data Analysis

This section discusses the morphological structures of the prime suffixes and the functions they perform in the Igbo language.

6.1. The Morphological Structures of the Prime Suffixes in Igbo Language

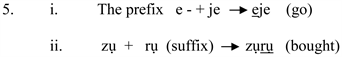

In terms of morphological structure, the prime suffixes in Igbo language have the syllable structure(s) thus:

a. [V] structure which can be any of these: a, e, i, ị, o, ọ, u, ụ.

b. [CV] structure as in:

c. [CVCV] structure as in:

From the structures above, it is observed the prime suffixes have varieties of syllable structures and tone patterns. They can be monosyllabic or disyllabic in nature. They are found only in the verbal slots. Their tones can change depending on the root of the verbs to which they are attached. The language observes vowel harmony but sometimes, these suffixes may or may not harmonize with the vowels of the root of the verbs which they are attached. The most significant thing is that they always give the verbs they are attached to different semantic meanings in the syntactic constructions. We can represent them on tree diagrams as shown in Figures 2-4 below respectively.

Figure 2. Configuration indicating VR and prime suffix.

Figure 3. Configuration indicating VR and prime suffix.

Figure 4. Configuration indicating VR and prime suffix.

6.2. The Morpho-Syntax and Semantic Classification of the Prime Suffixes Based on the Functions They Perform in the Verb Roots where They Are Attached in the Syntactic Structures in Igbo Language

In Igbo language, the prime suffixes are attached immediately after the verb roots. This implies that their position is solely restricted immediately after verb root. In this position where they are attached, they are capable of performing various semantic functions in the verbs where they are attached in the syntactic constructions. Therefore on their position where they are attached in the verb, functions are classified under the following headings:

1) Imperative function;

2) Negative function;

3) Past tense marker;

4) Progressive aspect marker;

5) Prepositional function;

6) Adverbial function.

6.3. Imperative Function

Imperative constructions are used to issue simple commands. Here the verb root is attached the OVS suffixes such as -a/-e, -o/-ọ to the express imperative or command that indicate the mood of the speaker. This implies that they can function as imperative markers. Syntactically, the behaviour of these suffixes in the verb forms can be inflectional and also extensional in some constructions like in the perfective aspect. The Igbo imperative suffixes are open vowel suffixes and they are always in high tones. Examples:

The configuration for 13(i), (ii) and (iii) which indicate the verb root and OVS which is the prime suffix as is shown in Figure 5 below.

Figure 5. Configuration indicating VR and prime suffix.

In the above data, the open vowel suffixes which are attached to the verb roots function as imperative markers that help to give the above constructions imperative meaning. The structure is thus [CV + OVS]. The underlined open vowel suffixes obey the rule of vowel harmony that operates in the language. Also, these underlined OVS are prime suffixes because of their position in the CV root. Consider the example below:

The verb sàa, sèe, gbùo and sùọ are the heads in the above phrases and it is the OVS suffixes that give them imperative readings. The above phrases have the same tree diagram but we are going to represented only 14(i) on tree as shown in Figure 6 below.

Figure 6. V'' configuration.

In the negative form, imperative in Igbo is formed by the attachment of the negative imperative suffix -la to the CV root to indicate prohibition. The suffix -la is always in a low tone. Examples:

Furthermore, the -rv suffix can also be attached to verb to indicate stative imperative meanings as in:

In examples 16(ii) and 17(ii), the -rv suffix that is attached to the verbs gives the verbs stative imperative meanings and they are also prime suffixes in those positions. The vowels of the CV root harmonize with the vowels of the -rv stative imperative marker. The mapping of the -rv suffix changes the inherent high tone of kwọ and bu to low tone in examples 16(ii) and 17(ii) respectively. The examples in 15(i) and 15(ii) have the same configuration as shown in Figure 7 below.

Figure 7. Configuration indicating prohibition.

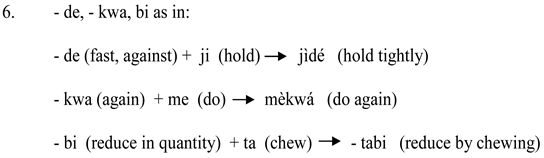

6.4. Negative Function

The negative suffixes are attached immediately as prime suffixes after the verb roots to perform different negative functions in Igbo language. Note that all the verbs in the negative constructions can take an obligatory harmonizing vowel prefix followed by the verb root and an appropriate negative suffix which is attached immediately after the root. The Igbo negative suffixes which can be used in expressing the negative notions are:

1) The general negative suffix -ghị;

2) The imperative negative suffix -la/-na;

3) The perfective negative suffix -beghị.

Each of these suffixes realizes negation differently in the syntactic structure(s). The general morpheme structure of the Igbo negative forms are:

[Á + CV + stem + suffix] verb.

6.5. The General Negative Suffix -ghị

The general negative suffix has the following morphemic constituents:

[Á + CV + stem + ghị] verb

Example 18(ii) can be represented on tree diagram as shown in Figure 8 below.

Figure 8. I'' Configuration indicating where the prime suffix is located.

The underlined suffixes above are prime suffixes and they have downstep tones in the above sentences.1) The imperative negative suffix -la/-naThe verb form has the following morpheme constituents:[Á + CV + la/na] verb.The vowel prefix is consistently in a high tone. The tone of the negative marker which is a prime suffix depends on the verb root. Examples:

The above example is shown in Figure 9 below.

Figure 9. Configuration indicating imperative negative suffix.

It is observed that the vowels of the imperative suffixes are on the same tone with the vowels their verb roots. In 20 (i and ii), they occur with high tone verbs that is why their tones are high while in 20 (iii), it occurs with the low tone verb that is why its tone is low. Both the tone of the vowel prefix and the suffix constitute meaning of the imperative notion.

2) The perfective negative suffix -bèghì̩

The perfective negative suffix is consistently on the low tone. The perfective negative suffix has a combination of two negative suffixes: the perfective marker -be and the general negator -ghị. The verb form has the following morpheme constituents thus:

[Á + CV + bèghì̩] verb.

Examples:

The above sentence can be represented as shown in Figure 10 below.

Figure 10. I'' Configuration indicating where the prime suffix is located.

From the foregoing, all these underlined suffixes are prime suffixes considering their position of occurrence in the verb root.

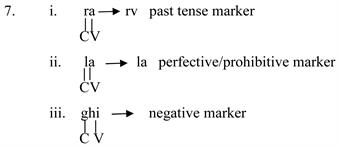

6.6. The Past Tense Marker

Tense is the form the verb takes to indicate time. In Igbo language, the past tense is indicated on the verb. The past tense shows that the action took place earlier than the time of speaking. In other words, it is the only way information about time frame of an action or event is realized inflectionally. The Igbo language uses the -rv inflectional suffix to express definite time meaning by attaching it immediately after the verb root as the prime suffix. The morpheme structure is thus: [CV + rv] verb.

Examples:

The -rv suffixes as used in examples 22(ii) and 23(ii) in the above sentences function as the past tense markers. In 24(ii) and 25(ii), they indicate present stative meanings on the verbs. The vowels of the CV roots harmonize with the vowel of the -rv inflectional suffix. The mapping of the -rv suffix unto the CV root changes the high tone of zụ to low tone in example 23(ii) so that the verb becomes low tone. The tone of the verbs that indicate tense in the past is consistently in a low tone. That is, the tense being past is the condition on the tone being low. (Mbah, 1999) represents it thus: If

Furthermore, past tense time meaning can be expressed in Igbo by the attachment of the suffixes -bụ and -bulu in verb root as prime suffixes as in:

The above data are semantically eventive. The suffixes function as past tense marker.

6.7. Progressive Aspect Marker

The suffixes -ga/-gha and -ge/ghe can be attached to the CV root to indicate progressive aspect in some Igbo dialects. Because of their position in the verb where they are attached, they are prime suffixes and function as the progressive aspect markers. Examples:

6.8. Prepositional Function

The Igbo verbs can take the bound suffixes which are attached immediately after the root to indicate prepositional functions or notions. The morpheme structure, we designate as -v and -vrv type (a vowel with a consonant and a vowel suffix ending) expresses the notion of benefactive and also translated in English as for, on, with, against, from respectively. Consider the examples below:

From the above examples, the -vrv suffix maps unto the verb roots and expresses the notion of benefactive. The final -rv marks the past tense while the medial V functions as the preposition. It indicates the notion of benefactive. The vowels of verb root harmonize with the prepositional vowel and -rv inflectional suffix. The prepositional vowel is always in a low tone.

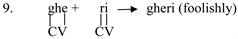

6.9. Adverbial Function

The prime suffixes can perform adverbial function when they are affixed to the verb root. The structure is thus: [CV + extndr] verb.

Examples:

The underlined extenders above indicate the manner of how the actions are performed in the sentences. That is, they specify adverbial function. The vowels in the verbs violate the rule of vowel harmony in the language. As regards to their positions in the verbs, they are regarded as the prime suffixes.

7. Conclusion

The study examines a functional analysis of the prime suffixes in Igbo with the objectives of classifying them according to the functions they perform on the verb root where they are attached in the syntactic constructions. The findings of the study reveal that the prime suffixes in Igbo language are overtly morphologically marked on the verb roots of the language. They occur immediately after the verb roots which implies that their position is restricted immediately after the verb root in the syntactic structures.

Some of them have the syllable structure thus [V] structure, others have [CV] or [CVCV] structure and can be monosyllabic or disyllabic in nature. They can perform various semantic functions such as imperative function, negative function, tense marker, progressive function, prepositional function and adverbial function. Some of the vowels of the verb roots do harmonize with the vowels of the prime suffixes while some do not. Sometimes the tones of the prime suffixes do change when they mapped unto the verb roots. The tones of the imperative suffixes are consistently in a high tone, while the tone of the -rv past tense marker is consistently on low. We, therefore, recommend that more research works be done in the grammar of the language to enhance its development by applying some of the linguistic theories in order to find out how they manifest in the grammar of the language.

This study will ignite novel interest in the minds of scholars towards in-depth study of various classes of suffixes as well as other aspects of grammar in human languages.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

Cite this paper

Ikegwuonu, C. N., & Egenti, M. C. (2019). A Functional Analysis of the Prime Suffixes in Igbo Morpho-Syntax. Open Journal of Modern Linguistics, 9, 254-273. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojml.2019.94024

References

- 1. Agbedo, C. (2015). General Linguistics: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives. Nsukka: KUMCEE-Ntaesho Press. [Paper reference 2]

- 2. Anoka, G. M. (1983). Selectional Restrictions. The Verb Meaning “to Buy”. In P. A. Nwachukwu (Ed.), Readings on the Igbo Verb (pp. 168-200). Nsukka: ILA. [Paper reference 1]

- 3. Anozie, C. N. (2007). General Linguistics: An Introduction. Enugu: Tashiwa Networks. [Paper reference 1]

- 4. Ejele, P. E. (1996). An Introductory Course on Language. Port Harcourt: University of Port Harcourt Press. [Paper reference 1]

- 5. Emenanjo, E. N. (1975). The Igbo Verbal. Unpublished MA Dissertation, Ibadan: University of Ibadan. [Paper reference 1]

- 6. Emenanjo, E. N. (1978). Elements of Modern Igbo Grammar: A Descriptive Approach. Ibadan: Oxford University Press. [Paper reference 7]

- 7. Emenanjo, E. N. (1982). Suffixes and Enclitics in Igbo. In F. C. Ogbalu, & E. N. Emenanjo (Eds.), Igbo Language and Culture (Volume 2, pp. 132-167). Ibadan: University Press Ltd.

- 8. Emenanjo, E. N. (2015). A Grammar of Contemporary Igbo: Constituents, Features, and Processes. Port-Harcourt: M&J Grand Orbit Communications Ltd.

- 9. Finch, G. (2000). Linguistics Terms and Concepts. New York: Palgrave. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-27748-3 [Paper reference 1]

- 10. Finegan, E. (2008). Language: Its Structure and Use. Boston, MA: Thomas Wadsworth. [Paper reference 1]

- 11. Green, M. M., & Igwe, G. E. (1963). A Descriptive Grammar of Igbo. London: Oxford. [Paper reference 4]

- 12. Haspelmath, M. (2002). Understanding Morphology. London: Hodder Education. [Paper reference 2]

- 13. Jackendoff, R. S. (1977). X-1 Syntax: A Study of Phrase Structure. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. [Paper reference 1]

- 14. Kari, E. E. (2015). Morphology: An Introduction to the Study of Word Structure. Port Harcourt: Pear Publishers. [Paper reference 1]

- 15. Mathews, P. (1991). Morphology (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139166485 [Paper reference 1]

- 16. Mbah, B. M. (1999). Studies in Syntax: Igbo Phrase Structure. Nsukka: Prize Publishers. [Paper reference 1]

- 17. Mbah, B. M. (2011). GB Syntax: A Minimalist Theory and Application to Igbo. Enugu: CIDJAP Press. [Paper reference 1]

- 18. Mmadike, B. I. (1998). Antecedent-Anaphor Relations in Orlu. Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation, Ibadan: University of Ibadan. [Paper reference 1]

- 19. Ndimele, O. M. (1999). Morphology and Syntax. Port-Harcourt: Emhai Printing and Publishing Co. [Paper reference 1]

- 20. Nnamdi-Eruchalu, G. (2007). An Introduction to General Linguistics. Enugu: John Jacob’s Classic Publishers. [Paper reference 2]

- 21. Nwachukwu, P. A. (1976). Readings on Igbo Verbs. Onitsha: African Feb Published. [Paper reference 1]

- 22. Nwachukwu, P. A. (1983). Stativity, Negativity and the rv Suffixes in Igbo. African Languages, 2, 119-144.

- 23. Ogbalu, F. C. (1972). School Certificate/GCE Igbo. Onitsha: University Publishing Company. [Paper reference 2]

- 24. Onukawa, M. C. (1999). The Order of Extensional Suffixes in Igbo. AAP. [Paper reference 1]

- 25. Onumajuru, V. C. (2008). Affixation and Auxiliaries in Igbo. http://muse.jhu.edu.chapter1811892 [Paper reference 2]

- 26. Quirk, E., & Greenbaum, S. (1973). A Universal Grammar of English. London: Longman. [Paper reference 1]

- 27. Radford, A. (1997). Syntax: A Minimalist Introduction. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [Paper reference 1]

- 28. Radford, A. (2004). English Syntax: An Introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511841675 [Paper reference 4]

- 29. Yul-Ifode, S. (2005). Affixation in Isoko. In O. M. Ndimele (Ed.), In Globalization & the Study of Language in Africa. Port-Harcourt: Grand Orbit Communication and Emhai Press. [Paper reference 1]