Advances in Anthropology 2013. Vol.3, No.3, 149-156 Published Online August 2013 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/aa) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/aa.2013.33020 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 149 Fertility Patterns and Reproductive Behaviours in the Lutheran and Catholic Populations from Historical Poland* Grażyna Liczbińska Faculty of Biology, Institute of Anthropology, Umultowska 89, Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznań, Poland Email: grazyna@amu.edu.pl Received March 5th, 2013; revised April 13th, 2013; accepted May 8th, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Grażyna Liczbińska. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Many variables of biological, ecological and cultural nature affect the biological dynamics of human populations. A religious denomination was an element of the cultural system which had an impact on the attitude towards birth control and sexuality. The aim of this paper is to show how religion shaped the fer- tility figures in the Catholic and Lutheran populations of historical Poland. Two methods were used to characterize fertility. One uses reconstructed individual histories of families to assess fertility figures on the basis of the length of protogenetic and intergenetic intervals. In the second method fertility measures were estimated from mortality and natural increase data. Using life-table parameters estimated for both stationary and stable population models the following fertility figures were calculated: crude birth rate, net reproductive rate R0, mean family size, mean birth interval, total fertility rate, and mean age-specific fertility rate. It has been found that the analyzed Catholic and Protestant populations from the territory of historical Poland were characterized by a rather high reproductive potential. Keywords: Protogenetic and Intergenetic Intervals; Partial Fertility Rate; Relative Cumulative Number of Births; Life Table Biometric Functions; Seasonality of Conceptions and Births Introduction In relation to historical populations many researchers have emphasized the role of religion in shaping the cultural identity of a community, as religious denomination is a central element of social identity. A system of religious values, which was im- plemented at the individual and communal levels, and spiritual and religious practices defined the relationship between the divine sphere and an individual, a group or a community. here- fore it is likely that these were translated into a demog- raphic behaviour (e.g.: Becker, 2008; Becker et al., 2010; Fern- gren, 1986; Galloway et al., 1994; Golde, 1975; Gugerli, 1992; Kemkes-Grottenthaler, 2003a, 2003b; Knodel, 1979, 1988; Knodel & Van de Walle 1979; Liczbińska, 2009a, 2009b, 2011, 2012a, 2012b; Lindberg, 1986; McQuillan, 1999, 2004; O’Connell, 1986; Van Poppel, 1992; Van Poppel et al., 2002; Schellekens & Poppel, 2006; Somers & Van Poppel, 2003; Wolleswinkel-van den Bosch et al., 1998, 2000). With regard to the populations of historical Europe resear- chers have emphasized the impact of religion on differences in fertility measures among the followers of the Catholic and Protestant denominations. If such differences were present, in their view, they resulted in a different approach to sexuality, family size and a conscious regulation of the number of off- spring. In the traditional doctrine of the Catholic Church mat- rimony was closely associated with procreation, and as such a sexual act was considered as a moral good. If, however, the sexual intercourse was consciously not connected with the act of procreation, this was regarded as morally wrong. A com- pletely different approach to this issue was taken by Protestant theologians who did not limit marriage to procreative functions, and saw in it something more. They treated marriage as a ful- filment of humanity, and stressed that the offspring is not the goal, but in the first instance its consequence. Married life and all aspects related to it was the private domain of the spouses, and the sexual act—contrary to the beliefs of the Catholics— was not a sin (Kuklo, 2009). The Catholics were strictly guided by the Catholic Church doctrine, which clearly influenced the size of the family. Therefore their families were larger com- pared with the Protestants. As such Catholic ideology shaped reproductive behaviour directly, as well as indirectly by deny- ing contraception and long breastfeeding, promoting having large numbers of children, and preaching teachings of the ap- propriate roles for the male and female in the family (McQuil- lan, 2004; Praz, 2009). Higher fertility measures among the Catholics compared with the Protestants were highlighted in Gold’s studies on Catholic and Protestant populations in Hohenlohe-Franken (Baden-Württemberg) region from the beginning of the 19th and the second half of 20th century (Golde, 1975), Van Poppel and colleagues (Van Poppel & Ről- ing, 2003; Schellekens & Van Poppel, 2006; Somers & Van Poppel, 2003) in 19th-century Netherlands, and McQuillan’s *Notes: This paper was presented in the form of a lecture delivered at The Population History Seminar organized by the Max Plank Institute for Demographic Research in Rostock, in September 2012.  G. LICZBIŃSKA research on demographic behaviour and its various factors among the Catholics and the Lutherans in 18th and 19th-cen- tury Alsace (McQuillan, 1999). Generally speaking, the Protes- tant populations often adopted their reproductive strategy to their conditions and needs, while the Catholic communities were less flexible in this regard (Livi-Bacci, 1979). This was especially evident after the French Revolution and birth of the Enlightenment movements, which included emancipation, re- sulting in an ongoing process of secularization of societies and therefore greater religious tolerance among the Protestants than the Catholics (Knodel, 1979; McQuillan, 1999). The literature makes particular mention that promotion of fertility control differed depending on religion. For example, decreases in fer- tility figures among the Catholics in Germany, the Netherlands, and Switzerland were delayed compared to other religious groups (Praz, 2003; Schellekens & Van Poppel, 2006). More- over, the Protestant communities experienced a relatively ho- mogeneous fertility transition compared to the more heteroge- neous one of the Catholics (Lesthaeghe & Wilson, 1979). Spa- tial differences in indicators related to fertility and nuptiality were also observed in 19th-century Prussia. It is evident that the strong East-West polarization in fertility figures observed here was linked not only to economic factors clearly dividing East and West Prussia, but also to the religious factor. Klüsener and colleagues (2012) have emphasized that although the numbers of Protestants on both sides of the border separating East Prus- sia from the West were equal, “the population of the regions that latterly formed the GDR had became more secularized than western Germany as early as the late 19th and early 20th cen- tury” (p. 85). Meanwhile, Kemkes-Grottenthaler (2003a) studying the vil- lages of the Land Rhineland-Palatinate in the 18th and 19th centuries inhabited by followers of the Catholic and Protestant denomination also pointed to the differences in fertility behav- iour. The higher fertility measures among the Catholics versus the Protestants were attributed by the researcher to a mainly religious context, but it was emphasized that religion should be regarded only as one of the factors affecting fertility. According to Kemkes-Grottenthaler (2003a), fertility is above all a func- tion of an individual approach to the family size, social condi- tions and finally—biological limitations. It is difficult to determine how religion shaped the biological dynamics of the territories of 19th-century Poland, as the object of the anthropological and demographic studies has been on the Catholic populations, and initially involving but few of these: the Czacz microregion (Borowski, 1976) and the parishes of Szczepanowo and Dziekanowice from Greater Poland (e.g.: Budnik & Liczbińska, 2013; Budnik et al., 2004; Dąbrowski, 2002; Domżol, 2002; Henneberg, 1977a, 1977b, 1978), Meł- giew (Modrzewska, 1948) and Bejsce from the Russian sector (Piasecki, 1983, 1990; Tymicki, 2004a, 2004b), the Silesian parish of Płużnica Wielka (former Duchy of Prussia; Puch, 1993) and the Little Poland village of Wielkie Drogi (the parish of Pobiedr, former Austrian sector; Puch, 1993). The unsatisfactory state of research in the field of historical anthro- pology thus makes further studies necessary. The aim of this study was to characterize fertility patterns and reproductive behaviours in the Lutheran and Catholic populations from historical Poland based on the current “state- of-the-art” concerning biological dynamics of populations of various regions of historical Poland and author’s own re- search. Material and Methods Two independent methods were used to assess fertility. First, drawing on information from birth, marriage and death registers the individual histories of women were reconstructed. Table 1 shows the selected populations for which measures of fertility calculated on the basis of the reconstructed individ- ual histories of families were taken from the literature or esti- mated based on literature data. The rural parishes of various regions of the 19th and early 20th century Polish territories are discussed in this paper. The Lutherans were represented by the Parish of Trzebosz from the borderland between Greater Poland and Silesia (see also Liczbińska, 2012a), and the Catholics by the following parishes: Szczepanowo from Greater Poland (Henneberg, 1977b, 1978; Henneberg & Kozak, 1976), Płużnica Wielka from the Duchy of Prussia (Puch, 1993), Wielkie Drogi from the Little Poland (Austrian sector; Puch, 1993), Krasne located in the vicinity of Rzeszów (Austrian sector; Rejman, 2006), and Bejsce from the Russian sector (Piasecki, 1983, 1990) (Table 1, Figure 1). Due to the nature of the data, we were not able to show changes over time in fertility measures. Therefore in this study we were limited to a discussion of differences in fertility figures for two periods: 1) the 19th century, and 2) the combined 19th and early 20th cen- tury. Fertility was assessed based on the length of protogenetic and intergenetic intervals. The protogenetic interval is an inter- val between the date of marriage, and thus the time of the onset of the regular sexual intercourse, and the date of birth of the Figure 1. Map of the studied localities as against territory of contemporary Po- land. Table 1. Populations under study (fertility measures obtained from reconstructed individual histories of families). Population N Religion Author Trzebosz 132 Lutheran Liczbińska, 2012a Bejsce 2020Catholic Piasecki, 1983, 1990 Krasne 1165Catholic Rejman, 2006 Płużnica Wielka 262 Catholic Puch, 1993 Wielkie Drogi 300 Catholic Puch, 1993 Szczepanowo 1128Catholic Henneberg, 1977b, 1978 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 150  G. LICZBIŃSKA Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 151 first child. Intergenetic intervals are defined as the periods be- tween the successive births. From the length of the intergenetic interval the partial fertility rate by the age of women can be calculated. This ratio reflects the number of births during the year by 1000 women aged x and is calculated by the formula: fx = 1000/ix, where fx is the fertility rate of women aged x years, and ix is the average length of the intergenetic interval (in years) in women aged x. In the populations with a very uneven level of fertility, a better measure of fertility than the partial fertility rate is the relative cumulative number of births Ux/Uc. It is de- fined as the ratio of the number of births given by women aged x years (Ux) to the total number of births by women who sur- vived to at least 45 years (Uc). This measure is the percentage of the total number of children born to women aged x in the studied population. Where it was too difficult to reconstruct the individual histo- ries of families, measures of fertility were estimated from mor- tality figures and natural increase data (Weiss, 1973; Table 2). Fertility in these cases was characterized for: 1) the second half of the 19th century, and 2) the combined second half of the 19th and early 20th century. With regard to the second half of the 19th century use was made of the populations according to the size of their place of residence. The Catholic parish of St. Mary Magdalene and the Lutheran parish of the Holy Cross were from the Poznań agglomeration. Small towns included are Kalisz (the Catholic parish of St. Joseph), Leszno (the Lutheran parish of the Holy Cross) and Bielsko (the Lutheran community of the Christ the Saviour’s), while two parishes were from the rural areas: Jastrzębsko Stare and Trzebosz (both of the Lu- theran denomination). The material for the second half of the 19th century and early 20th century was poorer than that for the first period and did not allow for dividing the populations ac- cording to the size of the place of residence. The Catholics are represented by the villages of Kuźnica and Jastarnia from the Hel peninsula and by the rural population from the Sierakowice county, while for the Lutherans by the rural parish of Trzebosz and the town community from Bielsko (Table 2; Figure 1). For the above-mentioned populations fertility figures were esti- mated from the life table parameters constructed for both sta- tionary and stable population models. The following fertility measures were calculated: 1) crude birth rate defined as the ratio of live births to the to- tal number of the living population in a given period and calcu- lated according to the formla 1 ω 0 x rx x x CBRe L − = − = = , where Lx is the number of years which will be survived by in- dividuals aged x, is a the middle of the age class, ω—age of the oldest individuals, r—the value of the natural increase; 2) net reproductive rate R0, which describes the replacement of generations and indicates how many individuals from a child generation will replace one adult from a parents’ generation. It is calculated according to the formula: R0 = erT. Here r is the value of the natural increase, and T is the duration of a genera- tion (in years); in this case it is calculated as the average age of the individuals aged 15 - 50 years, 3) mean family size defined as an average number of chil- dren born to a woman from a given population and calculated by the formula: MFS = 2R0/l15, in other words MFS = 2erT/l15, where l15 is a life table parameter idicating the fraction of indi- viduals surviving to 15 years of age; other symbols are as above. 4) mean birth interval defined as a period between successive births expressed in months: A = 12ef/MFS. The term ef is the number of years survived by an adult during the reproductive period. 5) total fertility rate defined as the average number of chil- dren born to a woman during her whole reproductive period, which is between 15 and 49 years and expressed as follows: TFR = 30MFS/ef, ef as above 6) mean age-specific fertility rate f—the ratio of the number of living deliveries by all women aged x and calculated from the length of intergenetic intervals according to the formula: f = 12/A. Results and Discussion Fertility Figures Estimated on Reconstructed Histories of Families Calculated fertility measures based on the reconstructed indi- vidual histories of families are presented in Tables 3-5. In the located on the borderland between Greater Poland and Silesia 19th-century Lutheran parish of Trzebosz the age of women giving birth to the first child was 25 years. This figure was over a year more than in the Catholic rural parish of Bejsce from the Russian sector (Piasecki, 1983, 1990) and 3 years more than in the Catholic parish of Krasne located in the vicinity of Rzeszów (territory of the Austrian sector; Rejman, 2006) (Table 3). The age of women giving birth to the last child ranged from 38 years (the Catholic parish of Krasne; Rejman, 2006) to almost 40 years (the Lutheran parish of Trzebosz), and even slightly exceeded this value (the Catholic parish of Bejsce; Piasecki, 1983, 1990). The age of women giving birth to the first and the last child calculated for the second half of the 19th and early 20th century practically did not change in Trzebosz (Liczbiń- Table 2. Populations under study (fertility measures obtained from mortality figures and natural increase growth). Population N Religion Author Poznań—St. Mary Magdalene Parish 6577 Catholic Author’s calculation Kalisz—St. Joseph Parish 4348 Catholic Author’s calculation Poznań—Holy Cross Parish 7157 Lutheran Author’s calculation Leszno—Holy Cross Parish 2561 Lutheran Author’s calculation Bielsko—Christ the Saviour’s Parish 6501 Lutheran Wrębiak, 2011 Trzebosz 312 Lutheran Author’s calculation Jastrzębsko Stare 878 Lutheran Author’s calculation Sierakowice county 3826 Catholic Budnik, 2005  G. LICZBIŃSKA Table 3. Average age at first birth and last birth (women with completed repro- duction cycle) in the Catholic and Lutheran populations from historical Poland. Period Population Religion Age—at-first birth Age—at-last birth Trzebosz1 Lutheran 25.32 39.84 Krasne2 Catholic 22.01 38.49 I Bejsce3 Catholic 23.80 40.30 Trzebosz4 Lutheran 25.50 39.60 II Bejsce3 Catholic 24.10 37.07 I: 19th century; II: the second half of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century; 1after: Liczbińska, unpublished date; 2after: Rejman, 2006; 3after: Piasecki, 1990; Tymicki, 2004a; 4after: Liczbińska, 2012a. Table 4. Number of offspring (women with completed reproduction cycle) in the Catholic and Lutheran populations from historical Poland. Period Population Religion Number of offspring Trzebosz1 Lutheran 6.4 Bejsce2 Catholic 6.1 Krasne3 Catholic 6.6 I Szczepanowo4 Catholic 5.4 Trzebosz5 Lutheran 6.7 II Bejsce6 Catholic 5.9 I: 19th century; II: the second half of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century; 1after: Liczbińska, unpublished date; 2after: Piasecki, 1990; 3after: Rejman, 2006; 4after: Henneberg, 1978; 5after: Liczbińska, 2012a; 6author’s calculation after: Piasecki, 1990. ska, 2012a), while in the Catholic Bejsce the average age of women at the last child birth was reduced by three years, sug- gesting that at the beginning of the 20th century the Bejsce women gave birth to the last child earlier than in the 19th cen- tury (Piasecki, 1983, 1990) (Table 3). Statistically significant differences between the Catholics and the Protestants were not recorded in the number of children born to a woman during her reproductive cycle (Table 4). In the 19th century, the average number of children per woman with the completed reproductive cycle ranged from 5.4 (the Catholic parish of Szczepanowo; Henneberg, 1977b) to 6.6 children (the Catholic parish of Krasne; Rejman, 2006). The Lutheran parish of Trzebosz is placed between them. Here, in the second half of the 19th century a woman bore on average 6.4 children. The same is true in the second period (the second half of the 19th and early 20th century): in Trzebosz the Lu- theran woman gave birth to on average 6.7 children (Liczbińska, 2012a), and in Bejsce a Catholic woman bore an average of 6 children (Piasecki, 1983, 1990) (Table 4). Knowing the age at the first and the last birth among the women with completed reproductive cycle, allows calculation of how much time from the whole reproductive period amounting to 34 years was de- voted to reproductive functions. In the case of the Lutheran women from Trzebosz the reproduction period in the 19th cen- tury amounted to 14 years, which corresponds to 43% of their reproductive capacity. In the Catholic parishes of Krasne and Bejsce women devoted to reproductive functions 47% of the entire reproductive period (Piasecki, 1990; Rejman, 2006) (Ta- ble 5). Table 5. Length of reproductive span and percentage of reproductive capacity in the Catholic and Lutheran populations from historical Poland. Period PopulationReligionReproductive span (in years) Reproductive capacity (in %) Trzebosz1Lutheran14 43 Krasne2 Catholic16 47* I Bejsce3 Catholic16 47* Trzebosz4Lutheran14 43 II Bejsce3 Catholic13 38* I: 19th century; II: the second half of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century; 1after: Liczbińska unpublished data; 2after: Rejman, 2006; 3after: Piasecki, 1990; 4after: Liczbińska, 20012a; *author’s calculation based on repro- ductive span in years. In Trzebosz similar values were obtained for the second half of the 19th and early 20th century, which confirms that at the beginning of the 20th century, the age at birth of the first and the last child did not change in comparison to the 19th century (see Table 3) and nor did the related length of the repro- duc- tion period (Liczbińska, 2012a). In Bejsce the reproduction capacity calculated for the second half of the 19th and early 20th century was lower than that in the 19th century, which confirms that at the beginning of the 20th century the length of the reproductive period of women was reduced (Piasecki, 1990; Rejman, 2006) (Table 5). Figure 2 shows the length of intergenetic intervals by age of women. As can be seen the shortest intervals characterized women in the age category 20 - 24 years and amounted to 26 months (the Catholic parishes of Płużnica Wielka and Wielkie Drogi; Puch, 1993), and 20 - 29 years (the Lutheran parish of Trzebosz and the Catholic parish of Szczepanowo; Henneberg, 1977b; Liczbińska, 2012a). The high fertility of women by the end of 29 years was confirmed by the value of the partial fertil- ity rates fx presented in this paper in the form of fertility curves (Figure 3). In Płużnica Wielka and Wielkie Drogi the highest values of fx rates were noted in the category of 20 - 24 years, after which the values of fx decreased (Puch, 1993). In the Lu- theran parish of Trzebosz and the Catholic parishes of Szcze- panowo and Bejsce the fx values were the highest in women aged 20 - 29 years, and from this age category they show a slow decrease (Henneberg, 1977b; Liczbińska, 2012a). All fertility curves presented in Figure 3 have the shape of a parabola, which indicates that the analyzed populations represent a model of fertility characteristic of non-Malthusian populations. The presented high fertility parameters among the Lutherans and the Catholics were finally confirmed by an analysis of the relative cumulative number of births (Ux/Uc). In all cases women prior to reaching the age of 25 years gave birth to more than 30% of the total number of children possible to achieve in their parishes, and by the end of age 29 years—to more than a half of off- spring in the total number of children possible to achieve in their populations (Figure 4). Although the populations discussed in the above-mentioned paper differed in their cultural and social traditions and were influenced by various partition legalities, their fertility figures confirmed a rather high fertility potential. High mortality rates of infants and young children may be one of the reasons of high reproduction capacity in the studied populations. Fertility after a child’s death may have increased in order to replace a lost Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 152  G. LICZBIŃSKA Figure 2. Length of successive intergenetic intervals (in months) by age of women at the moment of birth in the parishes from historical Poland. Trzebosz—after: Liczbińska, 2012a; Szczepanowo—after: Henneberg, 1977b; Płużnica Wielka and Wielkie Drogi—after: Puch, 1993. 0 100 200 300 400 500 600 15-19 20-24 25-29 30-34 35-3940-x years f x (per 1,000 birth Trzebosz-Lutherans Szczepanowo-Catholics Płużnica Wielka-Catholics Wielkie Drogi-CatholicsBejsce- C atholics Figure 3. Partial fertility rates in the parishes from historical Poland Trzebosz— after: Liczbińska, 2012a; Szczepanowo—after: Henneberg, 1977b; Bejsce—after: Piasecki, 1990; Płużnica Wielka and Wielkie Drogi— after: Puch, 1993. child. This fact has already been pointed to by many research- ers (e.g.: Gallowey et al., 1994; Knodel, 1979; Lesthaeghe & Wilson, 1979; Livi-Bacci, 1979; McQuillan, 1999; Piasecki, 1990). Despite the differences in the level of medical care and the standards of living conditions in the Polish territories in the Prussian, Austrian and Russian sectors, the studied populations were characterized by high infant and young children mortality rates (Henneberg, 1977a; Liczbińska, 2010; Piasecki, 1990; Puch, 1993; Rejman, 2006). It also seems evident that the high fertility in the presented parishes resulted from prevailing ecological and cultural condi- tions. Analysis of the annual rhythm of births (Figure 5) and the annual rhythm of conceptions as reconstructed from the former (Figure 6) shows that the pace and the time of repro- duction was regulated by religious norms governing sexual intercourse. Spouses abstained from sexual intercourse during Figure 4. Relative cumulative number of births in the parishes from historical Poland. Trzebosz—after: Liczbińska, 2012a; Szczepanowo—after: Henneberg, 1977b; Bejsce—author’s calculations after: Piasecki, 1990; Płużnica Wielka and Wielkie Drogi—author’s calculations after: Puch, 1993. Figure 5. Seasonality of births in the parishes from historical Poland. Trzebosz— after: Liczbińska, 2012a; Szczepanowo—after: Henneberg & Kozak, 1976; Bejsce—author’s calculations after: Piasecki, 1990; Płużnica Wielka and Wielkie Drogi—after: Puch,1993. Lent and Advent, and additionally—in rural agricultural popu- lations—in the period of intensive field works (Borowski, 1976; Budnik, 2005; Górna, 1984; Gralla, 1974; Henneberg & Kozak, 1976; Kuklo, 2009; Liczbińska, 2012a; Piasecki, 1990; Puch, 1993; Rejman, 2006). In the studied parishes the highest num- ber of conceptions was observed in the spring months (April- June) and in late autumn and winter (Figure 6). Therefore in spring, summer and early autumn, during the intensive field activities such as mowing, harvesting, lifting, ploughing and sowing, the smallest number of births was noted (Figure 5). In regard to the historical Polish territories, many researchers have pointed to coitus interruptus and sexual abstinence as the methods employed to prevent pregnancy. The inhibition of Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 153  G. LICZBIŃSKA Figure 6. Seasonality of conceptions in the parishes from historical Poland. Trzebosz-author’s calculations after: Liczbińska, 2012a; Szczepanowo —author’s calculations after: Henneberg & Kozak, 1976; Bejsce— author’s calculations after: Piasecki, 1990; Płużnica Wielka and Wiel- kie Drogi—author’s calculations after: Puch, 1993. ovulation and therefore postponement of the next pregnancy could also have been the result of prolonged breast-feeding. Induced abortion or even infanticides have also been stressed in the literature (Kuklo, 2009; Liczbińska, 2012a; Makowski, 1992; Piasecki, 1990). However, as the pace of reproduction of women in the 19th and the turn of the 19th and early 20th cen- tury was regulated, it remains doubtful that the rural communi- ties analyzed in this paper planned the number of children in their families in advance. Fertility Figures Based on Mortality Figures and Population Growth Rate The values of fertility measures based on the life table para- meters are presented in Tables 6-9. A picture of a population with a high potential of development emerges from them. In the second half of the 19th century the number of children per woman ranged from 4.5 to 5.5 (Table 6).The highest values of partial fertility rates (f) were recorded in the Lutheran parishes from Poznań and Bielsko, in the Catholic parish of St. Joseph in Kalisz and the rural parish of Jastrzębsko Stare. The conse- quences of the high value of TFR in the above-mentioned populations were the shortest intergenetic intervals obtained. The values of crude birth rate CBR were also very high (Table 6). The high fertility of women from the Lutheran parishes from Poznań and Bielsko, and from the Catholic parish of St. Joseph in Kalisz could have resulted of the fact that these par- ishes encompassed not only the city centre but also the subur- ban settlements and villages (Liczbińska, 2009a, 2009b, 2010, 2011; Rynkowska, 1979). The rural populations, likely more than the urban ones, adhered to the tradition of having a large number of children in the family (Liczbińska, 2009a), which is typical also for modern times (Budnik et al., 2003). The high reproductive potential of the Lutherans from the rural parish of Jastrzębsko Stare is not surprising (Table 6). After the introduction of the rate of natural increase to the sta- tionary population model, the fertility figures estimated on the basis of the biometric life table functions continue to indicate a Table 6. Fertility figures in the Catholic and Lutheran populations from histori- cal Poland in the second half of the 19th century (stationary population model). Population Religionf A MFS TFRCBR Poznań1 Catholic 0.2547.15 3.61 4.4937.72 Poznań1 Lutheran0.4129.55 4.63 5.6744.07 Kalisz1 Catholic 0.3831.66 4.35 5.5943.18 Leszno1 Lutheran0.2842.73 4.01 4.6435.34 Bielsko2 Lutheran0.3831.80 4.57 5.50- Trzebosz1 Lutheran0.2743.78 4.05 4.5633.95 Jastrzębsko1Lutheran0.4029.94 4.84 5.5640.21 1author’s calculation; 2after: Wrębiak, 2011. Table 7. Fertility figures in the Catholic and Lutheran populations from histori- cal Poland in the second half of the 19th century (stable population model). Population Religionf A MFS TFR CBRR0 Poznań1 Catholic0.2547.73 3.21 4.09 33.991.02 Poznań1 Lutheran0.3435.69 4.84 5.72 43.381.26 Kalisz1 Catholic0.3435.29 4.53 5.65 42.921.00 Leszno1 Lutheran0.2548.85 4.18 4.72 35.991.20 Bielsko2 Lutheran0.3831.47 4.57 5.50 - - Trzebosz1 Lutheran0.2548.68 4.14 4.60 34.431.14 Jastrzębsko1Lutheran0.2734.67 5.08 5.54 40.551.54 1author’s calculation; 2after: Wrębiak, 2011. high reproductive potential in the studied groups. The only difference observed is the decrease in the value of fertility rates f and the increase of the length of intergenetic intervals A (Ta- ble 7). These changes probably resulted from the fact that the introduction of the rate of natural increase into the stationary population model changed the distribution of the fraction of the deceases in various age categories. In each of the analyzed parishes, however, the net reproduction rate (R0) exceeded the value of 1, which indicates that in the future the mothers’ gen- eration would be replaced by the daughters’ generation. In other words, there was more than one daughter per a statistical woman (Tables 6 and 7). The second half of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century is represented in this study by the Kashubian populations (the Catholics from the Sierakowice County; Bud- nik, 2005) and Lutheran parishes from Trzebosz and Bielsko (Wrębiak, 2011). A high reproductive potential, reflected by high values of the crude birth rates CBR and fertility rates f, and short intervals between successive births A, was noted in the villages of the Sierakowice county (Budnik, 2005) (Tables 8 and 9). Only in the Lutheran community of the Bielitzer Zion (Wrębiak, 2011) and in the Lutheran parish of Trzebosz was an increase noted in length of intergenetic intervals compared to that in the second half of the 19th century. Longer intervals between successive pregnancies in these regions were a result of the decrease of the number of children in families in the early 20th century. Wrębiak (2011) in examining the Bielitzer Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 154  G. LICZBIŃSKA Table 8. Fertility figures in the Catholic and Lutheran populations from histori- cal Poland in the second half of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century (stationary population model). Population Religion f A MFS TFRCBR Sierakowice1 Catholic 0.49 24.56 5.20 6.2643.50 Jastarnia1 Catholic 0.31 39.21 4.21 4.9432.53 Kuźnica1 Catholic 0.37 32.23 4.41 5.5738.46 Trzebosz2 Lutheran 0.29 41.14 4.26 4.6633.66 Bielsko3 Lutheran 0.23 60.11 3.45 4.12- 1after: Budnik, 2005; 2author’s calculation; 3author’s calculation based on: Wrę- biak, 2011. Table 9. Fertility figures in the Catholic and Lutheran populations from histori- cal Poland in the second half of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century (stable population model). Population Religion f A MFS TFR CBRR0 Sierakowice1 Catholic 0.31 38.12 5.34 6.00 41.831.51 Jastarnia1 Catholic 0.22 55.32 4.50 4.94 35.131.49 Kuźnica1 Catholic 0.25 47.20 4.93 5.63 40.601.62 Trzebosz2 Lutheran 0.24 50.62 4.38 4.68 34.451.26 Bielsko3 Lutheran 0.21 61.15 3.51 4.10 - - 1after: Budnik, 2005; 2author’s calculation; 3author’s calculation based on: Wrę- biak, 2011. Zion has pointed out that the explanation for this be sought “in the ageing structure of the population and in the decline in the number of young women” (p. 301) rather than from conscious efforts for family planning in advance. A slow pace of ageing of the Lutheran populations was also observed in the parish of Trzebosz in the borderland between Greater Poland and Silesia. The landed estates belonging to the Lutheran parish fell in the early 20th century into Polish hands, which resulted in an out- flow of certain groups of parishioners, especially young people (Liczbińska, 2012b). In Trzebosz the elderly parishioners, set- tled here for a generation, were the only people remaining in the parish (Evangelishes Konsistorium, Position Number 6782; Liczbińska, 2012b). Thus, as in Bielsko, the fertility figures obtained are the result of the cultural context of this community rather than from the conscious planning of the number of chil- dren in relation to the religious factor. Conclusion 1) The analyzed Catholic and Protestant populations of Po- lish historical territories were characterized by a high reproduc- tion potential. This was confirmed by the high values of fertility figures calculated from the reconstructed individual histories of women and on the basis of the life table biometrics functions. 2) Even if the pace of reproduction of women from the stu- died populations was regulated, it remains doubtful that the number of children in their families was consciously planned in advance. It seems most likely that fertility in the analyzed groups was a result of environmental and cultural conditions, and not nec- essarily associated with the parents’ conscious needs of having the number of offspring planned in advance. Acknowledgements Special thanks are accorded to Barbara Zuber Goldstein, Siegfried Gruber, Sebastian Klűsener and Mikołaj Szołtysek, for many helpful comments, suggestions and discussions. Thanks are also extended to the Dean of the Faculty of Biology of the Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań for the financing of the article processing charges. REFERENCES Becker, S. O. (2008). Luther and girls: Religious denomination and the female education gap in nineteenth-century Prussia. Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 110, 777-805. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9442.2008.00561.x Becker, S. O., Cinnirella, F., & Woessmann, L. (2010). The trade-off between fertility and education: Evidence from before the demo- graphic Transition. Journal of Economic Growth, 15, 177-204. doi:10.1007/s10887-010-9054-x Borowski, S. (1976). Procesy demograficzne w mikroregionie Czacz w latach 1598-1975. Przeszłość Demograficzna Polski, 9, 95-156. Budnik, A. (2005). Uwarunkowania stanu i dynamiki biologicznej populacji kaszubskich w Polsce. Studium antropologiczne. Poznań: Wydawnictwo Naukowe UAM. Budnik, A., & Liczbińska G. (2013). Biological and cultural causes of seasonality of deaths in historical populations from Poland. Col- legium Antropologicum. Budnik, A., Liczbińska, G., & Gumna, I. (2004). Demographic Trends and Biological Status of Historic Populations From Central Poland: The Ostrów Lednicki Microregion. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 125, 369-381. doi:10.1002/ajpa.10272 Budnik, A., Mrowicka, B., & Baran, S. (2003). The fertility of women in Poland in the period of transformation of the political and eco- nomic system (80’s and 90’s). Human Evolution, 18, 243-250. doi:10.1007/BF02436290 Dąbrowski, R. (2002). Ocena stopnia wewnątrzgrupowego spokrewnienia ludności z mikroregionu Ostrowa Lednickiego w XIX i początkach XX wieku—Analiza izonomii. Studia Lednickie, 6, 111-126 Domżol, M. (2002). Ocena stanu puli genów na podstawie analizy odległości małżeńskich w populacjach wiejskich z mikroregionu Ostrowa Lednickiego na przełomie XIX i XX wieku. Studia Led- nickie, 6, 127-141. Ferngren, G. B. (1986). The evangelical-fundamentalist tradition. In: R. L. Numbers, & D. W. Amundsen (Eds.), Caring and curing: Health and medicine in the western religious traditions (pp. 486-451). New York: Macmillan Publishing Company. Galloway, P., Hammel, E. A., & Lee, R. D. (1994). Fertility decline in Prussia, 1875-1910: A pooled cross-section time series analysis. Population Studies, 48, 135-158. doi:10.1080/0032472031000147516 Golde, G. (1975). Catholics and protestants. Agricultural moderni- zation in two German villages. London: Academic Press. Górna, K. (1984). Sezonowość ruchu naturalnego ludności ewange- likiej w parafii Rząśnik w latach 1794-1874. Sobótka, 4, 563-571. Gralla, G. (1974). Urodzenia i zgony w parafii Ziemięcice w powiecie gliwickim w latach 1651-1888. Przegląd Antropologiczny, 40, 369- 374. Gugerli, D. (1992). Protestant pastors in late eighteenth-century Zu- rich: Their families and society. Journal of Interdisciplinary History, 22, 369-385. doi:10.2307/204985 Evangeliches Konsistorium, Position Number 6782. Henneberg, M. (1977a). Ocena dynamiki biologicznej wielkopolskiej dziewiętnastowiecznej populacji wiejskiej. I. Ogólna charakterystyka demograficzna. Przegląd Antropologiczny, 43, 67-89. Henneberg, M. (1977b). Ocena dynamiki biologicznej wielkopolskiej dziewiętnastowiecznej populacji wiejskiej. II. System kojarzeń i płodność. Przegląd Antropologiczny, 43, 245-272. Henneberg, M. (1978). Ocena dynamiki biologicznej wielkopolskiej dziewiętnastowiecznej populacji wiejskiej. III. Opis stanu puli genów Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 155  G. LICZBIŃSKA Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 156 na podstawie danych demograficznych. Przegląd Antropologiczny, 44, 33-52. Henneberg, M., & Kozak, J. (1976). Sezonowość urodzeń w wiejskiej populacji dziewiętnastowiecznej: parafia Szczepanowo (woj. Bydgo- skie. Pałuki). Przegląd Antropologiczny, 42, 19-31. Kemkes-Grottenthaler, A. (2003a). More than a leap of faith: The im- pact of biological and religious correlates on reproductive behaviour. Human Biology, 75, 705-727. doi:10.1353/hub.2003.0076 Kemkes-Grottenthaler, A. (2003b). God, faith and death: The impact of biological and religious correlates on mortality. Human Biology, 75, 897-915. doi:10.1353/hub.2004.0006 Klűsener, S., Szołtysek, M., & Goldstein, J. R. (2012). Towards an integrated understanding of demographic change and its spatio- temporal dimensions: Concepts, data needs and case studies. Die Erde, 143, 75-104. Knodel, J. E. (1988). Demographic behaviour in the past. A study of fourteen villages’ populations in the eighteenth and nineteenth cen- turies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511523403 Knodel, J. (1979). Demographic transitions in German villages. In A. J. Coale, & S. C. Watkins (Eds.), The decline of fertility in Europe (pp. 337-389). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Knodel, J., & Van de Walle, E. (1979). Lessons from the past: Policy implications of historical fertility studies. In A. J. Coale, & S. C. Watkins (Eds.), The decline of fertility in Europe (pp. 390-419). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Kuklo, C. (2009). Demografia Rzeczypospolitej przedrozbiorowej. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo D i G. Lesthaeghe, R., & Wilson, C. (1979). Models of production, seculariza- tion, and pace of the fertility decline in Western Europe, 1870-1930. In A. J. Coale, & S. C. Watkins (Eds.), The decline of fertility in Europe (pp. 261-292). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Liczbińska, G. (2009a). Infant and child mortality among Catholics and Lutherans in nineteenth century Poznań. Journal of Biosocial Science, 41, 661-683. doi:10.1017/S0021932009990101 Liczbińska, G. (2009b). Umieralność wśród katolickiej i ewangelickiej ludności historycznego Poznania. Poznań: Biblioteka Telgte. Liczbińska, G. (2010). Diseases, health status, and mortality in urban and rural environments: The case of Catholics and Lutherans in 19th-century Greater Poland. Anthropological Review, 73, 21-36. doi:10.2478/v10044-008-0019-z Liczbińska, G. (2011). Ecological conditions vs. religious denomination. Mortality among Catholics and Lutherans in nineteenth-century Poznań. Human Ecology, 39, 795-806. doi:10.1007/s10745-011-9428-5 Liczbińska, G. (2012a). Fertility and family structure in the Lutheran population of the Parish of Trzebosz in the second half of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century. The History of the Family, 17, 142-156. doi:10.1080/1081602X.2012.669120 Liczbińska, G. (2012b). Marriage patterns among Lutherans from the Parish of Trzebosz in the second half of the 19th century and the be- ginning of the 20th century. The History of Family, 17, 236-255. doi:10.1080/1081602X.2012.713557 Lindberg, C. (1986). The Lutheran tradition. In R. L. Numbers, & D. W. Amundsen (Eds.), Caring and curing: Health and medicine in the western religious traditions (pp. 173-203). New York: Macmillan Publishing Company. Livi-Bacci, M. (1979). Social-group forerunners of fertility control in Europe. In A. J. Coale, & S. C. Watkins (Eds.), The Decline of fertil- ity in Europe (pp. 182-200). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Makowski, K. (1992). Rodzina poznańska w I połowie XIX wieku. Poznań: Wydawnictwo UAM. McQuillan, K. (1999). Culture, religion, and demographic behaviour: Catholics and Lutherans in Alsace, 1750-1970. Montreal & Kingston: Liverpool University Press and Mc Gill-Queen’s University Press. McQuillan, K. (2004). When does religion influence fertility? Popula- tion and Development Review, 30, 25-56. doi:10.1111/j.1728-4457.2004.00002.x Modrzewska, K. (1948). Parafia Mełgiew jako biologiczny krąg izolacyjny. Annales Universitatis Mariae Curie—Skłodowska, 3, 79- 140; O’Connell, M. R. (1986). The Roman Catholic traditions since 1545. In R. L. Numbers, & D. W. Amundsen (Eds.), Caring and curing: Health and medicine in the western religious traditions (pp. 108- 145). New York: Macmillan Publishing Company. Piasecki, E. (1983). Charakterystyka demograficzna dawnej rodziny polskiej. Przeszłość Demograficzna Polski, 14, 100-121. Piasecki, E. (1990). Ludność parafii bejskiej (woj. kieleckie) w świetle ksiąg metrykalnych z XVIII-XX w. Warszawa-Wrocław: Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe. Praz, A-F. (2003). Politique conservatrice et retard Catolique dans la baisse de la fécondité: l’Example du canton de Fribourg en Suisse. Annales de Demographie Historique, 2, 33-55. Praz, A.-F. (2009). Religion, masculinity and fertility decline. A com- parative analysis of Protestant and Catholics culture (Switzerland 1890-1930). The History of Family, 14, 88-106. doi:10.1016/j.hisfam.2009.01.001 Puch, E. A. (1993). Dynamika biologiczna polskich społeczności wiejskich z różnych systemów społeczno-kulturowych w XVIII i XIX wieku. Przegląd Antropologiczny, 56, 5-36. Rejman, S. (2006). Ludność podmiejska Rzeszowa w latach 1784-1880. Studium demograficzno-historyczne. Rzeszów: Wydawnictwo Uni- wersytetu Rzeszowskiego. Rynkowska, A. (1979). Sytuacja ekonomiczna i społeczna robotników kaliskich w XIX wieku. In A. Gieysztor, & K. Dąbrowski (Eds.), Osiemnaście wieków Kalisza (pp. 271-318). Poznań: Wydawnictwo Poznańskie. Schellekens, J., & Van Poppel, F. (2006). Religious differentials in marital fertility in The Hague (Netherlands) 1860-1909. Population Studies, 60, 23-38. doi:10.1080/00324720500430758 Somers, A., & Van Poppel, F. (2003). Catholic priests and the fertility transition among Dutch Catholics, 1935-1970. Annales de Dé- mographie Historique, 2, 57-88. Tymicki, K. (2004a). Reproductive behaviour in historical population of Bejsce parish. The demographic analysis of parish registers re- construction data from Bejsce, 18th-19th century, Poland. PhD Dis- sertation. Warsaw: Warsaw School of Economics. Tymicki, K. (2004b). Kin influence on female reproductive behavior: The evidence from reconstruction of the Bejsce Parish rgisters, 18th to 20th Centuries, Poland. American Journal of Human Biology, 16, 508-522. doi:10.1002/ajhb.20059 Van Poppel, F. (1992). Religion and health: Catholicism and regional mortality differences in nineteenth-century Netherlands. Social His- tory and Medicine, 5, 229-253. doi:10.1093/shm/5.2.229 Van Poppel, F., & Rőling, H. (2003). Physicians and fertility control in the Netherlands. Journal of Interdisciplinary History, 34, 155-185. doi:10.1162/002219503322649462 Van Poppel, F., Schellekens, J., & Liefbroer, A. (2002). Religious differentials in infant and child mortality in Holland, 1855-1912. Population Studies, 56, 277-289. doi:10.1080/00324720215932 Weiss, K. M. (1973). A method for approximating age—Specific fertil- ity in the construction of life tables for anthropological populations. Human Biology, 45, 195-210. Wolleswinkel-van den Bosch, J. H., Van Poppel, F. W. A., Looman, C. W. N., & Mackenbach, J. P. (2000). Determinants of infant and early childhood mortality levels and their decline in The Netherlands in the late nineteenth century. International Journal of Epidemiology, 29, 1031-1040. doi:10.1093/ije/29.6.1031 Wolleswinkel-van den Bosch, J. H., Van Poppel, F. W. A., Tabeau, E., & Mackenbach J. P. (1998). Mortality decline in the Netherlands in the period 1850-1992: A turning point analysis. Social Science & Medicine, 47, 429-443. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(98)00060-4 Wrębiak, K. A. (2011). Zjawiska biodemograficzne i stan biologiczny XIX-wiecznego Bielskiego Syjonu. PhD Dissertation. Kraków: Jagiellonian University.

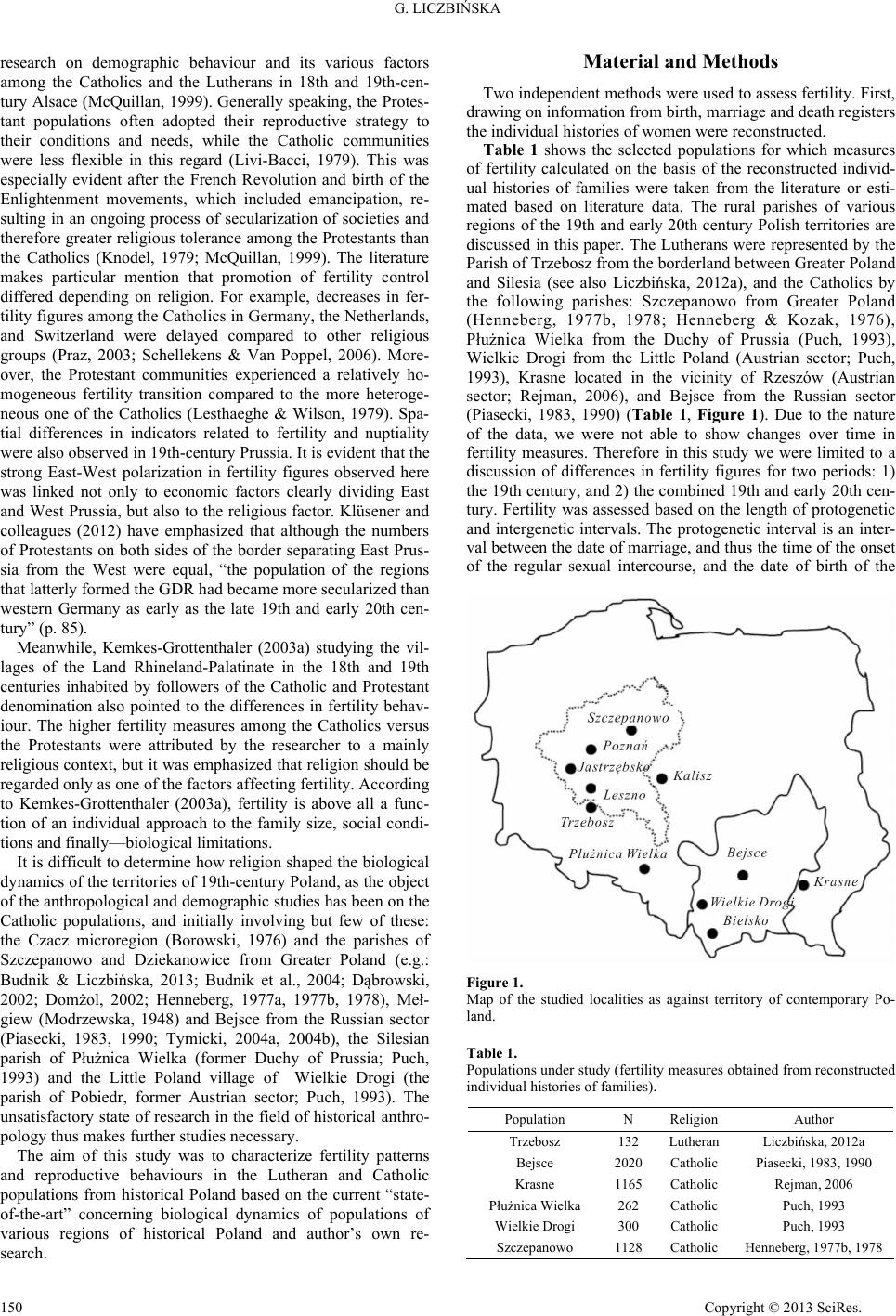

|