Early Quality Life Impairment in Alzheimer Disease’s Patients in Geriatric Department: About 214 Cases in Pitié Salpêtrière Hospital of Paris (France) ()

1. Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is characterized by a progressive decline in memory and other cognitive abilities that stems from atrophy, synapse loss, accumulation of amyloid plaques and tangles neurofibrillary on hippocampic then neocortical regions of the brain. AD is a neurocognitive disorder (NCD) decline often associated with behavioral changes such as depression, apathy, agitation, or disinhibition [1] , and in some combination, these factors lead to functional decline with a gradual loss of autonomy in performing activities of daily living (ADL) [2] . Although cognitive impairment is usually considered the primary determinant of functional decline in AD, several studies have linked behavioral deficits to inability in physical self-care like in activities of daily living activity [3] and particularly rapid loss of functional autonomy [3] [4] . In some cases, the relationship between behavioral deficits and ADL decline is independent of cognitive deficiency [4] [5] [6] . The early identification and assessment of these disorders can help to establish a diagnosis, propose a treatment and predict the prognosis of Alzheimer’s disease [7] .

2. Materials and Methods

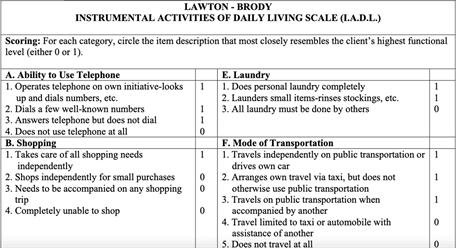

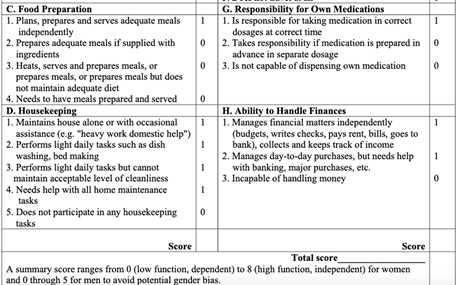

This is a retrospective observational study over 14 years (2005-2019) on data from the CHU Pitié Salpêtrière Geriatric Department which concerned: All patients followed or consulting a geriatrician, nurse, neuropsychologist for neuro-cognitive disorders with MA according to diagnosis criteria and having a first neuropsychological assessment at a day hospital, a completed IADL and NPI form (see Figure A in Appendix).

The means of collection were: the data of the entered service filled in Excel, the NAS 56 server, Orbis software, the paper files in the archiving room to collect the different points of each item of the IADL and NPI scores.

We used IADL form of Lawton including the attitude or aptitude to do 14 forms of special and daily living activities: using the phone, going shopping, using transport, responsibility for taking medication and managing money, cleanliness, ability to eat food and dress, personal care, displacement or shift and take bath. NB: We have by convention defined a sheet of instrumental activities of daily life IADL adapted on 11 points by concealing 3 items (Housekeeping, Food preparation, Laundry) allowing a homogeneous analysis and interpretation of the data. Indeed, it was difficult to differentiate between aptitude = possibility of carrying out an activity and attitude = objective realization of the activity. These activities were frequently listed as not applicable because of the presence of a third party doing it long before, but sometimes there is the problem of their attribution to gender depending on the culture.

Housekeeping, laundry and food preparation place greater demands on both executive and motor skills.

For the NPI score, we used the 12 points. Delusional ideas, hallucinations, agitation, depression, anxiety, exaltation, disinhibition, apathy, behavior Disorder, irritability sleep and appetite. The total point result of crossing the frequency and gravity of each point.

The information about IADL and NPI items was collected by caregivers’ interviews.

Non-inclusion criteria: other related diagnoses (vascular dementia, Body Lewy disease, mixed dementia, frontotemporal dementia (DFT), Inoperable file: IADL, NPI and YH files not fulfilled, file empty or not found. The initial hypothesis is null.

Variables study:

Global Profile of Adapted IADL and NPI in MA Disease

• Adjustment according to age groups

• Adjustments by gender

• Adjustment according to the presence or absence of a motor disorder

• Adjustment according to comorbidities

• Adjustment according to MMSE-BREF

The probability of having impairment in Activity daily living or instrumental activity daily living was the same. For the statistical analysis, we used the Chi2 test with a significative P value < 0.05.

3. Results

The mean age was 82.1 years old with women predominance (63%) without polypathology (CIRS-52 ≤ 4 57%). At the early stage of MA, the major patient had moderate neurocognitive disorder according by the means to MMSE, IADL, NPI scale and conserved abilities according to Hoen Yahr scale.

Achievement of basic ADL quality of life (cleanliness, food, dressing) is significantly more impaired compared to specialized life activities in patients aged 68-80 at the time of diagnosis.

Impairment of basic and specialized quality of life (responsibility for treatment = 25, Dressing = 66%, Cleanliness = 66%) is more frequent in men than in women at the time of diagnosis. Polypathology statically influences basic and specialized quality of life (cognitive and motor in AD at the time of diagnosis.)

4. Discussions and Comments

In our study, the means sociodemographic variables, cognitive status, IADL and NPI profiles were shown in Figure 1.

The early overall profile of IADL mentioned in Figure 2 functional impairment of AD diagnosis, independently of the variables, affected specialized cognitive activities much more (55.6%), mainly (management of medications = 33.6%,

![]()

Figure 1. Chart flow of files and means of variables studied. IADL = instrumental Activity Daily living, NPI = Inventaire Neuropschiatrique, Cirs = cumulating Illness rating scale, BREF = Batterie Rapide Efficience Facile; MMSE = mini-mental examination statement; HY = Hoen Yahr.

![]()

Figure 2. Activities about course, the responsibility of treatment and management in IADL were reduced in AD at the time of diagnosis.

management of finances = 54.6%) while the overall achievement was 75% for the basic ADL functional activities including movement (51.4%) of AD at early diagnosis. Several studies reported that impaired cognitive functions were associated with a reduction in IADL in the early stage of AD, whereas this impairment is much more frequently associated with basic life activities in advanced forms. Therefore, basic and specialized quality-of-life assessment could help predict the risk of developing cognitive impairment in AD patient [8] [9] [10] . In our study and after adjustment, patient in the age group between 68 and 80 years had a statistically significant higher early achievement (P < 0.05) of ADL functional activities of basic life (Food = 67%, Cleanliness = 68% and Personal Care = 78%) versus IADL specialized activities than in the over 80 age group. IADL impairment of specialized and basic activities was generally more severe in men than women. Polypathology (CIRS-52 > 4) influenced statistically on IADL cognitive functional impairment through treatment management (28%), financial management (41%) and telephone (75%) compared to basic life activities suggesting the need for primary and secondary prevention of comorbidities associated to AD earlier. (Table 1)

The cognitive status influenced the IADL activities (Table 2). When the cognitive and executive level decreases, the cognitive test (MMSE (<20) and BREF (<10) profile of the IADL functional impact is also significantly more affected like in the management of medication (11%) and financial (10%). Also, when the MMSE (≥20) or BREF (≥10) corresponds to a moderate to normal cognitive and executive level, the IADL functional impairment is early in the management of treatments (64%), shopping (74%) and travel (92%) compared to ADL functional impairment of basic activities. This tendency seems classic in AD where the amnesic syndrome is present from the onset of the disease.

![]()

Table 1. Distribution of IADL by age, sex and comorbidities.

![]()

Table 2. Distribution of IADL By MMSE-BREF and HY of AD patients.

When the MMSE-BREF is lower the instrumentals and daily living activities are more affected and vice versa.

In the absence of motor functional disorders according to the Hoen Yahr Scale, the cognitive IADL functional impairment is more affected, particularly in the management of medication (74%) and shopping (82%). Several studies report that impaired cognitive status assessed by the MMSE was associated with NPI disorders and could be used to predict early neuropsychological and behavioral disorders of AD [11] . The severity of these disorders was associated with a low MMSE [7] .

In our study, the overall profile of the quality of life on the NPI score found in Figure 3 was characterized by the predominance of psychological impairment (apathy = 432%), behavioral (irritability = 235%) and psychotic disorders (hallucinations = 147%) and appetite (419%).

Beyond the age of 80, the disorders of the NPI were more significant, in particular psychological (Apathy = 611%; depression = 325%), then behavioral (behavioral disorders = 337%, irritability = 307%, appetite 301%) and psychotic (delusions = 216% and agitation = 247%) compared to patients in the 68 - 80 age group in which the same pattern of damage was found with less severity. This profile of severity seems more frequent in women over 80 years old with apathy-depression, irritability and delusions in a statistically significant way, although AD is more frequent in women in our study (Table 3). In Natalia and al study, apathy, agitation, depression, hallucinations, anxiety, disinhibition, and eating disorders were significantly higher in the early stage of patients with AD due likely to the multifactorial and includes both social and biological factors at the receiving of diagnostic [12] [13] .

In a review of the literature, executive and neuropsychiatric disorders such as apathy and depression are generally associated and interdependent in the moderate form associated with a decline in basic and specialized life activities and found in women [8] [11] [14] [15] .

![]()

Figure 3. There was a predominance of apathy, irritability, depression, and anxiety in AD at early diagnosis.

![]()

Table 3. Distribution of NPI by aged-sex and comorbidities in AD patient.

NPI symptoms were more severe beyond the age of 80 years in women.

In the absence of poly pathology, the NPI disorders seem statistically more important, in particular, depression = 278%; Aberrant motor behavior = 276%, sleep disorder = 125% and delusions = 201%. When the cognitive and executive level decreases MMSE (<20) -BREF (<10) the profile of psycho-behavioral disorders was severe in apathy (308%) and aberrant behavior (178%). If the MMSE-BREF increases, the psychological disorders, motor behavior and appetite were more severe respectively affected (apathy = 616%, 272 = % and 282%).

The low cognitive level does not seem to influence too much on the types of NPI disorders. We found the same profile of the severity of psychological disorders (Apathy = 919%; depression = 491%, Anxiety = 466%), behavioral (Irritability = 504%; aberrant motor behavior = 469% and appetite = 407%) and psychotics (delirium = 320% and agitation = 377%) in the absence of a functional gene according to the HY scale (HY = 0).

Affective disorders displayed the highest prevalence from early AD (52.7%) to severe dementia due to AD (98.2%). Also, aberrant motor behavior displayed a higher prevalence between early AD group to severe dementia due to AD with statistical significance respectively. In patients with dementia due to AD, hallucination and depression were more prevalent in females (P = 0.001) [16] .

5. Conclusion

At early diagnostic of AD, the IADL activities that were most affected in young elderly increased with poly pathology. the neuropsychological and behavior disorders was frequent in the oldest elderly women.

Appendix

Annexe 8: Neuropsychiatric-Inventory

Idées délirantes

Le patient/la patiente croit-il/elle des choses dont vous savez qu’elles ne sont pas vraies? Par exemple, il/elle insiste sur le fait que des gens essaient de lui faire du mal ou de le/la voler. A-t-il/elle dit que des membres de sa famille ne sont pas les personnes qu’ils prétendent être ou qu’ils ne sont pas chez eux dans sa maison? Est-il/elle vraiment convaincu(e) de la réalité de ces choses?

□ Oui □ Non

Si Oui

A quelle fréquence cela se produit t-il? Par semaine

□ Moins d’une fois □ environ une fois □ plusieurs fois □ presque tous les jours

Quel est le degré de gravité (degré de perturbation pour le patient)

□ Léger □ moyen □ important

Hallucinations

Le patient/la patiente a-t-il/elle des hallucinations? Par exemple, a-t-il/elle des visions ou entend-il/elle des voix? Semble-t-il/elle voir, entendre ou percevoir des choses qui n’existent pas?

□ Oui □ Non

Si Oui

A quelle fréquence cela se produit t-il? Par semaine

□ Moins d’une fois □ environ une fois □ plusieurs fois □ presque tous les jours

Quel est le degré de gravité (degré de perturbation pour le patient)

□ Léger □ moyen □ important

Agitation / Agressivité

Y-a-t-il des périodes pendant lesquelles le patient/la patiente refuse de coopérer ou ne laisse pas les gens l’aider? Est-il difficile de l’amener à faire ce qu’on lui demande?

□ Oui □ Non

Si Oui

A quelle fréquence cela se produit t-il? Par semaine

□ Moins d’une fois □ environ une fois □ plusieurs fois □ presque tous les jours

Quel est le degré de gravité (degré de perturbation pour le patient)

□ Léger □ moyen □ important

Dépression / Dysphorie

Le patient/la patiente semble-t-il/elle triste ou déprimé(e)? Dit-il/elle qu’il/elle se sent triste ou déprimé(e)?

□ Oui □ Non

Si Oui

A quelle fréquence cela se produit t-il? Par semaine

□ Moins d’une fois □ environ une fois □ plusieurs fois □ presque tous les jours

Quel est le degré de gravité (degré de perturbation pour le patient)

□ Léger □ moyen □ important

Anxiété

Le patient/la patiente est-il/elle très nerveux(se), inquiet(ète) ou effrayé(e) sans raison apparente? Semble-t-il/elle très tendu(e) ou a-t-il/elle du mal à rester en place? Le patient/la patiente a-t-il/elle peur d’être séparé(e) de vous?

□ Oui □ Non

Si Oui

A quelle fréquence cela se produit t-il? Par semaine

□ Moins d’une fois □ environ une fois □ plusieurs fois □ presque tous les jours

Quel est le degré de gravité (degré de perturbation pour le patient)

□ Léger □ moyen □ important

Exaltation de l’humeur / Euphorie

Le patient/la patiente semble-t-il/elle trop joyeux(se) ou heureux(se) sans aucune raison? Je ne parle pas de la joie tout à fait normale que l’on éprouve lorsque l’on voit des amis, reçoit des cadeaux ou passe du temps en famille. Il s’agit plutôt de savoir si le patient/la patiente présente une bonne humeur anormale et constante, ou s’il/elle trouve drôle ce qui ne fait pas rire les autres?

□ Oui □ Non

Si Oui

A quelle fréquence cela se produit t-il? Par semaine

□ Moins d’une fois □ environ une fois □ plusieurs fois □ presque tous les jours

Quel est le degré de gravité (degré de perturbation pour le patient)

□ Léger □ moyen □ important

Apathie / Indifférence

Le patient/la patiente a-t-il (elle perdu tout intérêt pour le monde qui l’entoure?

N’a-t-il/elle plus envie de faire des choses ou manque-t-il/elle de motivation pour entreprendre de nouvelles activités?

□ Oui □ Non

Si Oui

A quelle fréquence cela se produit t-il? Par semaine

□ Moins d’une fois □ environ une fois □ plusieurs fois □ presque tous les jours

Quel est le degré de gravité (degré de perturbation pour le patient)

□ Léger □ moyen □ important

Désinhibition

Le patient/la patiente semble-t-il/elle agir de manière impulsive, sans réfléchir? Dit-il/elle ou fait-il/elle des choses qui, en général, ne se font pas ou ne se disent pas en public?

□ Oui □ Non

Si Oui

A quelle fréquence cela se produit t-il? Par semaine

□ Moins d’une fois □ environ une fois □ plusieurs fois □ presque tous les jours

Quel est le degré de gravité (degré de perturbation pour le patient)

□ Léger □ moyen □ important

Irritabilité / Instabilité de l’humeur

Le patient/la patiente est-il/elle irritable, faut-il peu de choses pour le/la perturber? Est-il/elle d’humeur très changeante? Se montre-t-il/elle anormalement impatient(e)?

□ Oui □ Non

Si Oui

A quelle fréquence cela se produit t-il? Par semaine

□ Moins d’une fois □ environ une fois □ plusieurs fois □ presque tous les jours

Quel est le degré de gravité (degré de perturbation pour le patient)

□ Léger □ moyen □ important

Comportement moteur aberrant

Le patient/la patiente fait-il/elle les cent pas, refait-il/elle sans cesse les mêmes choses comme par exemple ouvrir les placards ou les tiroirs, ou tripoter sans arrêt des objets?

□ Oui □ Non

Si Oui

A quelle fréquence cela se produit t-il? Par semaine

□ Moins d’une fois □ environ une fois □ plusieurs fois □ presque tous les jours

Quel est le degré de gravité (degré de perturbation pour le patient)

□ Léger □ moyen □ important

Sommeil

Est-ce que le patient/la patiente a des problèmes de sommeil (ne pas tenir compte du fait qu’il/elle se lève uniquement une fois ou deux par nuit seulement pour se rendre aux toilettes et se rendort ensuite immédiatement)? Est-il/elle debout la nuit? Est-ce qu’il/elle erre la nuit, s’habille ou dérange votre sommeil?

□ Oui □ Non

Si Oui

A quelle fréquence cela se produit t-il? Par semaine

□ Moins d’une fois □ environ une fois □ plusieurs fois □ presque tous les jours

Quel est le degré de gravité (degré de perturbation pour le patient)

□ Léger □ moyen □ important

Appétit/Troubles de l’appétit

Est-ce qu’il y a eu des changements dans son appétit, son poids ou ses habitudes alimentaires? Est-ce qu’il y a eu des changements dans le type de nourriture qu’il/elle préfère?

□ Oui □ Non

Si Oui

A quelle fréquence cela se produit t-il? Par semaine

□ Moins d’une fois □ environ une fois □ plusieurs fois □ presque tous les jours

Quel est le degré de gravité (degré de perturbation pour le patient)

□ Léger □ moyen □ important