The Impact of Microfinance on Grassroot Development: Evidence from Smes in Kwabre East District of Ashanti Region of Ghana ()

1. Introduction

Scholarly articles on the perspective of people and groups in the grassroots averred that they are the common or ordinary people in the society with less power and resources. They are highly vulnerable for exploitation by the elite in the society and are dominant in rural and peri-urban communities. It is perceived that people in the grassroots are deeply in the poverty net and most often lack the basic necessities for shelter, jobs, food, health, education and sound environment. Some writers [1] described people at the grassroots as those who most often lack the most basic of human necessities for housing, employment, food, health-care, education, and a clean and safe environment.

Any development intervention of people at the grassroots is poverty alleviation focused. Grassroots development do not only champion the elevation of the well-being and empowerment of people and groups but also broaden their horizons in making choices and taking investment opportunities thereby bringing about positive change in their standard of living. Anchored in grassroots development is the development of enterprises. This is because the grassroots are dominant in these enterprises. At the grass root, the active poor are those at the grassroots who run enterprises known as micro, small or medium enterprises [2] .

Microfinance has since been recognized as the main vehicle for poverty alleviation. This recognition of microfinance especially the micro-credit component has received global attention as echoed by the UN General Assembly [3] and Ehali and Danopoulos [4] . Generally, microfinance is the provision of financial and non-financial services to the poor on sustainable basis. These services of microfinance include microcredit, savings, micro insurance, money transfer services and business advisory services.

Empirical evidence attests to the overwhelming role of microfinance and in particular microcredit in poverty alleviation, improvement in the standard of living of the poor, financial inclusion and the achievement of the Millennium Development Goals [5] [6] [7] [8] [9] . Irrespective of the red flag and cautions raised about the efficacy of microfinance and in particular microcredit in poverty reduction [10] [11] ; microfinance has been proven to be effective tool in poverty reduction with potentials for raising the standard of living of the poor and the vulnerable.

Since poverty reduction is rooted in grassroots development, the positive impact of microfinance on grassroots development cannot be gainsaid. Equally important in this regard is the recognition of the development of SMEs as a sine quo non for grassroots development, poverty alleviation and empowerment. This empirical study on the impact of microfinance on SMEs at Kwabre East District of Ashanti Region of Ghana would not only underpin the far-reaching impact of microfinance on grassroots development but would lay bare the increasing recognition of micro enterprise development as pivotal for grassroots development agenda, poverty alleviation and empowerment.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Review

2.1.1. Grassroots and Grassroots Development

Grassroots are mostly ordinary men at the lowest class of the social ladder who are deeply in the poverty net and lack the basic necessities of life. They are vulnerable, the poor working class and predominantly domicile in rural communities or urban neighborhoods [12] . Development can be defined as growth in production and changes in the quality of life of people. Grassroots development is therefore the sustained strategies geared toward growth in the economy of nations and positive changes in the standard of living of people at the grassroots. From the perspective of the Inter-American Foundation of Virginia-USA, grassroots development is a community-based change through participatory, self- initiatives [13] . The primary objective is to improve the quality of life for the poor and disadvantaged.

In 1994, the Inter-American Foundation developed a framework called the Grassroots Development Framework (GDF) to evaluate the impact of its own projects on grassroots development. As shown in Figure 1 below, the GDF looked at three broad areas in impact assessment namely: direct benefits, strengthening organizations and broader impact. The Framework considers both tangible and intangible results from these areas. The detailed version of the GDF as indicated in Figure 2 defined the three broad areas of direct benefits, strengthening organizations and broader impact to be individual families, organizations and society (local, regional, national) in that order. The key indicators of both tangible and intangible results underpinning the framework are shown in Figure 2.

![]()

Figure 1. The Grassroots Development Framework (GDF)― [Credit: Inter-American Foundation].

![]()

Figure 2. The Grassroots Development Framework (GDF)-Detailed Version. [Credit: Inter-American Foundation].

2.1.2. Microfinance

Microfinance is generally defined as the provision of financial and non-financial services to the poor on sustainable basis. These services of microfinance include microcredit, savings, micro insurance, money transfer services, pension remittances and business advisory services targeted at low-income groups and enterprises [14] . The activities of microfinance include practical services provided on how the loan acquired is invested and the means to save the revenue generated from the business. Training and development, education, small enterprise management, trust building and among others are some activities of microfinance institutions. The provision of loans is therefore not the only activity of microfinance operations.

Many approaches and models of microfinance have been utilized in microfinance operations. The approaches include Welfarist and Institutional [15] [16] [17] [18] whilst the models of microfinance delivery encapsulate Individual Lending, Group or Peer Lending, Grameen Bank, Village Banking and Rotating Savings and Credit Associations [19] [20] [21] [22] .

According to Asiama [23] microfinance started as a self-help group among the rural poor and in Africa microfinance was first established in the Northern region of Ghana by Canadian Catholic missionaries in the year 1955. He averred that successive government in Ghana has developed varying strategic programmes aimed at reducing poverty and ensuring that the standards of living of the low income earners are enhanced [23] . This culminated into three main operators of microfinance in the formal, semi-formal and informal sectors of the financial service industry in Ghana. The formal sector players of microfinance are Savings and Loans Companies, Rural and Community Banks and Commercial Banks; and the semi-formal sector comprise of the Credit Union Associations, Financial Non-Governmental Organizations (FNGOs), and Cooperatives. The informal sector operators of microfinance in Ghana are made up of Susu Collectors and Clubs, Rotating and Accumulating Savings and Credit Associations, Traders and Moneylenders.

2.1.3. The Concept of Smes

SMEs are generally deemed to be formal economic entities. They are dominant in the private sector of economies and comprise of individuals and entrepreneurs with the potential for creativity, innovation and skills development. Attempts to define SMEs have made use of quantitative variables of number of employees, assets and turnover [24] [25] [26] [27] . The use of these variables in the definition of SMEs has attracted criticisms making the definition debatable in the development arena. Many jurisdictions make use of the number of employees in the concept of SMEs. In Ghana, the National Board for Small Scale Industries (NBSSI) classify enterprises as:

1. Micro Enterprise: less than 6 employees;

2. Small Enterprise (6 - 29) employees;

3. Medium Enterprise (30 - 99) employees and;

4. Large Enterprise (100 and more) employees.

2.2. Empirical Review

Berguiga [18] raised a question to find out if the positive of microfinance depends on a specific characteristics of SMEs. He answered the question through the examination of the population benefitting from microloan. It was concluded that microloan best suit particular types of individuals, namely micro entrepreneurs belonging to the higher sub group of petty traders with potentials for ($2 dollars a day per capita) who are endowed with entrepreneurial capacities which are reinforced by professional experience, training and education [28] [29] .

Hulme and Mosley [10] conducted impact studies on thirteen MFIs located in seven countries which operated between 1989 and 1993. Their findings revealed that extension of loans had a positive effect on the income of small and medium enterprises borrowers. They also indicated that very poor micro and small enterprise aim at subsistence credit to weak or low interest loan.

Other impact studies are consistent to the impact of microfinance on small and medium enterprises. Doligez [30] showed a comparative analysis done in Guinea, Nicaragua, Benin and Burkina Faso of the situation of recipients versus non-recipients of micro loan. It was established that recipients undertake productive ventures and broaden their sources of income, which they also improve and stabilize the average income drawn from their business activities [31] .

It has also been stressed that if MFIs are to fully fulfill their missions of deepening financial intermediation among petty traders then it is for them to evaluate the impact of microfinance in reducing poverty and improving the living condition of their beneficiaries [32] . A study conducted on cross section of Microfinance institutions confirmed the positive impact of accessibility of microfinance services on beneficiary clients. These were improvement in the quality of life, increased income levels, enhanced self-confidence and livelihood security [14] . Littlefield, Murduch and Hashemi [7] also indicated that microfinance interventions have shown a positive impact on the education of their clients’ children.

A cursory look at the above assertions showed that microfinance has led to grassroots development. Microfinance has brought direct benefits to individual families. These benefits are both tangible and intangible results posited by the GDF of the Inter-American Foundation as shown in Figure 2. Microfinance interventions provide people with monetary capital to boost their occupation or business and also enhance their sense of dignity, thus empowering them to participate in the economy [33] . Microloan best suit micro entrepreneurs belonging to the higher sub group of petty traders with potentials for skills development [28] [29] . Microfinance has impacted positively on SMEs income or profitability [34] . The provision of microfinance services assists small and medium enterprises to enhance their livelihood activities and security [35] . Accessibility to microfinance do not only results in the improvement in the quality of life, increased income levels, enhanced self-confidence and livelihood security of benefiaciaries but also impact positively on the education of their clients’ children [7] [14] .

The impact of microfinance on grassroots development manifests in direct benefits to individual families, strengthening of organizations and broader impact on society as pronounced the GDF of the Inter-American Foundation. This is because of the overwhelming positive impact of microfinance on SMEs development thereby enabling the SME subsector to build institutions and have broader impact.

Poverty reduction is a key role played by SMEs in developing economies [36] [37] . Snodgrass and Biggs [38] argue that, SMEs create employment opportunities than large firms because SMEs are more labour intensive. Okpukpara [39] also argues that SMEs in most African countries, contribute significantly

towards poverty alleviation through production and employment creation. Other functions of SMEs include training and capacity building. They contribute to the total revenue generation of government through the payment of taxes and other income levies. SMEs also help increase the standard of living of individuals since they realized some income from their work.

2.3. Profile of the Case Study Adopted [Kwabre East District of Ashanti]

According to the District Analytical Report released by the Ghana statistical Service in 2014, the Kwabre East District is one of the thirty Administrative Districts of the Ashanti Region of Ghana [40] . It was historically part of Kwabre Sekyere District until it was carved out in 1988. It became Kwabre East District after Afigya Kwabre District was carved out of the Kwabre District in 2007. The District was established by Legislative Instrument (L.I) 1894. Its capital, Mamponteng, is approximately 14.5 kilometers from Kumasi. According to the 2010 Population and Housing Census the District’s population stands at 115,556, with 47.7 percent of males while the remaining proportion is females [40] .

The report also stated that the District is the home of kente, the traditional Akan cloth with different varieties. Also, other traditional cloths are made within the District. There is a weaving industry at Adanwomase. Other kente weaving settlements include Sakora Wonoo, Abira, Kasaam and Bamang. Ntonso is also noted for its famous Adinkra industry. Every year many tourists visit these settlements to acquaint themselves with information about the industry. Ahwiaa is also noted for wood carvings and attracts a lot of tourists [40] . Figure 3 shows the map of the study area.

![]()

Figure 3. Map of kwabre east district. Source: Ghana Statistical Service, GIS.

3. Methodology

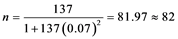

The research was a case study type and descriptive in nature. The focus of the research was on SMEs in Kwabre East District of Ashanti Region of Ghana in analyzing the impact of microfinance on grassroots development. Descriptive statistics were used to illustrate data gathered from the field survey for analysis and discussions. The field survey produced data from 82 sampled SMEs out of the target population of 137 registered SMEs with the Business Advisory Centre of the NBSSI in the District. The sample size was obtained by using the mathematical sample model of Ahiabor [41] stated below:

where:

n = sample size;

N = population;

e = error.

Using a confidence level of 93% and registered population of SMEs with the Business Advisory Centre of NBSSI in Kwabre East District, the sample size of the study was 82 as calculated below.

The field survey produced data from 82 SMEs. The survey was done through the administration of structured questionnaires. The questionnaires produced data on demographic characteristics of respondents and impact of microfinance on business operations and standard of living.

The sampling techniques used included the non-probability methods of purposive and convenience. The sampled 82 SMEs were purposely selected from the registered database of the Business Advisory Centre of the NBSSI in the District. Convenience sampling was used to identify respondents who were readily available. In all 82 set of structured questionnaires was used to gather data from the SMEs. The response rate from the questionnaire administration was 100%. Both qualitative and quantitative techniques were utilized in the data analysis.

4. Discussion and Results

The actual findings from the survey are analyzed and discussed below.

4.1. Demographic Characteristics

As indicated in Table 1 below, 59% of the respondents interviewed in the survey were males whilst the females constituted 41%. About 57% of the respondents were in the age bracket of 31 - 50 years whilst 33% were in the 51 - 61 age brackets. Also 41% of the respondents were married and 44% divorced. About 10% of the respondents were single and 4% widowed.

About 95% of the respondents have had some form of basic education indicating relatively literate SMEs. This may be attributed to the fact that the research focused on registered SMEs. Registration connotes formality attesting to the relative literate nature of the respondents. However, only 21% of the respondents had tertiary level of education. The fact that 5% had no formal education depicts the generally held view that the SMEs sub-sector in Ghana is devoid of illiteracy. It also underscored the grassroots focused nature of the study consistent to Pilisuk et al. [1] description of people in the grassroots as those who most often lack the basic of human necessities like education.

![]()

Table 1. Demographic characteristics.

Source: Field Survey, (2017).

Of the SMEs interviewed, about 98% employed below 29 workers and only 2% had employment numbers in the range of 29 - 99. This is consistent to the National Board for Small Scale Industries (NBSSI)’s classification of SMEs in Ghana. About 56% of the SMEs interviewed had been in operation for over 5years; 17% in the range of 2 - 5 years; and 27% up to 1 year.

4.2. Impact of Microfinance on SMES

As shown in Table 2, 40% and 38% of SMEs interviewed said that microfinance has increased their business capital and stock level respectively. This is consistent to the findings of Berguiga [18] who posited that the inception of microfinance has made it possible and easier for SMEs that could not access services from the traditional banks to obtain capital as start-ups and to widen their capital base. It also confirmed the stance of Ferka [33] that microfinance interventions have helped a lot of people by granting them monetary capital for their occupation or business. However, 60% and 62% of the respondents answered to the contrary when asked whether microfinance has increased their capital and stock levels respectively. Whilst 46% of the respondents answered in the affirmative that microfinance has enabled them to meet customers’ demands, 54% answered in the negative.

![]()

Table 2. Impact of microfinance on SMEs.

Source: Field Survey, (2017).

In relation to business profit, 40% of the respondents said that microfinance has increased their profit whilst 38% averred that it has increased their volume of sales. This attested to the real impact of microfinance institutions on SMEs income or profitability pronounced by Montalieu [34] ; Robinson [14] ; and Hulme and Mosley [10] . However, 60% and 62% of the respondents said that microfinance has not increase their profit and volume of sales respectively.

On the impact of microfinance on their living conditions 46%, 44% and 54% of the respondents said that microfinance has enabled them met household expenses; paid school fees; and acquired properties respectively. This is consistent to the assertion of Johnson and Rogaly [35] that the provision of microfinance services assists small and medium enterprises to enhance their livelihood activities and security. It also corroborates the position of Littlefield et al. [7] that microfinance interventions have shown positive effects on the education of beneficiary clients’ childred. However, 54%; 56%; and 44% of the respondents answered in the negative when asked whether microfinance has enabled them met household expenses; paid school fees; and acquired properties in that order. Whilst 46% of the respondents said that microfinance has increased their savings level, 54% of them indicated no.

Respondents confirmed the positive impact of microfinance on their capacity. This was in terms of financial security; confidence; skills; operational efficiency; and assess to business advisory services. As shown in Table 2, 56% of the respondents said that microfinance has enhanced their financial security but 44% answered to the contrary. Whilst 54% of the SME operators indicated that microfinance has boosted their confidence in business management, 46% answered in the negative. In an answer to the question whether microfinance has improved their skills in record keeping, 54% of the respondents said Yes and 44% responded No. Also 46% of the respondents answered Yes to the assertion that microfinance has increased their operational efficiency but 54% of them said No. Whilst 76% of the respondents confirmed that microfinance has ensured access to business advisory services, 24% rejected that proposition.

It can be inferred from the above results that microfinance has some level of impact on grassroots development. The impact is of direct benefits to individual operators of SMEs and their families. Both tangible impact on standard of living and personal capacity easily come to the fore. Ingredients of tangible impact on standard of living include basic needs; knowledge and skills; employment and income; and assets [Figure 2]. Indicators of self-esteem, creativity and critical reflection can be said of personal capacity [Figure 2]. This is consistent to the Grassroots Development Framework for impact assessment of grassroots development champion by the Inter-American Foundation [Figure 2].

However, evidence from the survey was not explicit on the impact of microfinance on strengthening organizations and broader impact on society in relation to local, regional and national as demanded by the Grassroots Development Framework [Figure 2]. Irrespective of the assertion by Ferka [33] that microfinance interventions have helped a lot of people by granting them monetary capital to boost their occupation or business and also enhance their sense of dignity, thus empowering them to participate in the economy-depicting a seemingly broader impact, the expected impact of microfinance on grassroots development according to the Grassroots Development Framework (GDF) on all levels of organizations and society was not evidenced from the survey [Figure 2]. The desired of GDF that grassroots development should produces results at different levels cannot be said to have been well articulated from the survey. The impact of microfinance on organizations relative to organizational capacity and culture; and on society with regards to policy environment and community norms called for further research.

5. Conclusions

Microfinance has proven to be the effective vehicle for poverty reduction with potential for transformation of the standard of living of low income households and the vulnerable. Since poverty alleviation is rooted in grassroots development, the positive impact of microfinance on grassroots development cannot be overemphasized. Equally significant in this regard is the recognition of the development of SMEs as sine quo non for grassroots development, poverty alleviation and empowerment. The study adopted the Grassroots Development Framework (GDF) pioneered by the Inter-American Foundation for impact assessment of development interventions on grassroots development.

It was evidenced that microfinance as a development intervention has some level of impact on grassroots development. The impact is of direct benefits to individual operators of SMEs and their families. These included positive impact on basic needs; knowledge and skills; employment and income; and assets. Other positive effects of microfinance on grassroots development in the case of SMEs operators were self-esteem, creativity and critical reflection.

However, findings from the survey are not explicit on the impact of microfinance on strengthening organizations and broader impact on society in relation to local, regional and national as demanded by the Grassroots Development Framework (GDF). The researcher therefore recommends for further studies the impact of microfinance on organizations in respect of organizational capacity and culture, and on society with regards to policy environment and community norms.

It was revealed that microcredit remained the dominant feature of microfinance in making significant impact. The hurdle of accessibility to credit by SMEs has not been completely cleared. Over 60% of the respondents posited that microfinance has not increased their business capital and stock levels. The researcher makes far-reaching recommendations for accessibility to credit by SMEs and the strengthening of MFIs to enable them resilient in financial intermediation and provision of non-financial services.

Amongst others, there should be sustained relationship of MFIs and microfinance clients geared toward improved service delivery and customer satisfaction. This should lead to continued dialogue aimed at removing obstacles in credit delivery. Additionally, capacity building and business advisory services for SMEs embarked upon by the Business Advisory Centre of NBSSI should not only be vigorous but also monitored and evaluated to ensure the desired impact. There should be periodic impact assessment of such programmes targeted on SMEs to get the needed feedback for effective implementation and achievement of objectives.

Also the District Assembly should factor in its development plans activities for the development of SMEs including supporting the entrepreneurial development programmes of the Business Advisory Centre of NBSSI in the district. Further, the central government should create the enabling environment for private sector development. These include policies aimed at reinvigorating sound macroeconomic fundamentals. Additionally, there should be sustainable energy supply and infrastructure development.

Towards robust MFIs, the Bank of Ghana should amongst others strengthen its regulatory and supervisory functions with the aim of improving capital adequacy, liquidity, assets quality and profitability of MFIs. In addition, corporate governance systems of MFIs should be built on the premises of clear corporate governance principles, guidelines and best practices. These would not only make the MFIs sustainable but also viable channels in financial intermediation.