Current Account & Real Exchange Rate Dynamics in the Caribbean and Latin America Compared to the G7 Countries ()

1. Introduction

Empirical analyses of the impact of temporary and permanent shocks on the real effective exchange rate and the current account testing the colloquial predictions of the intertemporal model of Obstfeld and Rogoff [2] have mainly been concentrated on the G7 and Asian countries, see Chinn and Lee [3] [4] ; Lee and Chinn [1] ; Shibamoto and Kitano [5] ; Affandi and Mochtar [6] among others. Little empirical evidence has been gathered from the Caribbean and Latin American emerging market economies. Here the dynamics of real exchange rate and current account movement remains relevant as countries experiment with exchange rate strategies to get a better understanding of the policy framework needed to stimulating aggregate output and increasing international trade.

In theory, the sticky price model of Obstfeld and Rogoff [2] proposes that temporary monetary shocks should have a greater effect on the current account in the short run, but no effect in the long run while permanent shocks to productivity should have little effect on current account, but a positive real permanent shock interpreted as technological advancement, should induce a permanent appreciation of the real exchange rate. A temporary shock interpreted as a monetary innovation should induce a temporary depreciation of the real exchange rate and an improvement of the current account. Evidence of this has been found with minor differences in the G7 and Asian countries. See for example, Lee and Chinn [1] and Affandi and Mochtar [6] .

The Global Financial Crisis in 2008 was associated with sharp appreciation of the real effective exchange rate (REER) for Caribbean and Latin American countries1 see panel B on Figure 1 illustrating quarterly real effective exchange rate for Argentina (AREER), Bolivia (BOREER), Chile (CHREER), Costa Rica (COREER), Columbia (COLREER), Jamaica (JREER), Mexico (MREER), Paraguay (PARAREER) and Peru (PERUREER). Notice the REER for these countries appeared to be converging just before the Global Financial Crisis of 2008, see panel A on Figure 1. Prior to the Crisis, between 2005 and

![]()

Figure 1. Quarterly Real Effective Exchange Rate (REER) for selective Caribbean and Latin American Countries.

2008, the REER for Argentina, Chile, Jamaica and Mexico Chile were higher than the other countries, however, appeared to be meandering downwards, showing signs of appreciation. While the REER for Bolivia, Columbia, Costa Rica, Paraguay and Peru were the lower than the others but appeared to be meandering upwards showing signs of depreciation. They all remained relatively stable just up to the Global Financial Crisis of 2008, where there is a significant declining shock (appreciation) of the REER for all the countries in the Sample followed by a small sharp upturn (depreciation) in 2009, see panel B on Figure 1. After which, the REER for these selected group of Caribbean and Latin American countries gradually diverged from each other from 2010 onwards as each country administered its own policy in response to the after math of the Global Financial Crisis in 2008, see panel C on Figure 1. The REER for Argentina, Chile, Columbia, Mexico, Peru has been meandering with a downward trend showing signs of appreciation while the REER for Bolivia, Costa Rica, Jamaica and Paraguay have been meandering with an upward trend showing signs of depreciation, see panel C on Figure 1.

Figure 2 illustrates the quarterly current account to GDP ratios for Argentina (ARCGDP), Bolivia (BOCGDP), Chile (CHCGDP), Costa Rica (COCGDP), Columbia (COLCGDP), Jamaica (JCGDP), Mexico (MCGDP), Paraguay (PARACGDP) and Peru (PERUCGDP) from 2005 to 2014. Notice that a larger variation is present in the current account to GDP ratios for the selected countries before the Global Financial Crisis of 2008, see panel D on Figure 2. Subsequently, the data become denser with less variation and a minor downward trend after the Global Financial Crisis of 2008, see panel E on Figure 2. The current account to GDP ratios for all these countries have been trending towards zero, displaying less variability after the shock from the Global Financial Crisis gradually disappears. The current account balance for these countries meandered between −2.8% and +3.2% of GDP per quarter prior to 2008. After which, the gap narrowed as variations meandered between −2% and +1%.

![]()

Figure 2. Quarterly current account to GDP ratios for selective Caribbean and Latin American Countries.

Of all the countries in the sample, Jamaica has the worst current account to GDP ratio averaging as low as −3% of GDP in the third quarter of 2008, Jamaica’s current account to GDP balance has remained consistently negative; annual current account to GDP deficit was less than −13% in 2013. The deficit however, has been improving under the supervision of the International Monetary Fund IMF as a part of the latest Extended Fund Facility. The Bank of Jamaica has allowed the market to predominantly determine the value of its currency, by practicing less sterilization policies. As it relates to the Latin American countries, the current account as a percentage of GDP for Costa Rica and Columbia averaged below zero. Argentina has the highest current account balance as a percentage of GDP; their current account to GDP ratio displays sharp increases and decreases, maintaining an average above 2.0 percent per quarter up to 2010. Afterwards, the average per quarter fell marginally below zero.

An analysis of the impact of temporary and permanent shocks on the exchange rate and current account of these Latin American and Caribbean countries is necessary to get a more holistic understanding of the similarities or cross country differences that might exists. These economies remain susceptible to external shock including temporary monetary shocks and permanent productivity shocks, however little research exists to analyse the impact of shocks on the viability these lesser developed and emerging market economies.

Our objective is to analyse the interrelationship between the real exchange rate and current account in Jamaica, Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Columbia, Costa Rica and Mexico, Paraguay and Peru in a structural VAR framework. The research employs the methodology proposed by Lee and Chinn [1] 2 who examined the same issue for G7 countries. We identify our model by imposing the Blanchard and Quah [7] long run restriction that temporary shocks have no long run impact on the real exchange rate, consistent with the open economy macroeconomic models of Obstfeld and Rogoff [2] and the intertemporal approach to the current account. Additionally, the assumption is made that global shocks have no effect on the current account and the exchange rate. Country specific shocks however, can impact both variables.

The rest of the paper is organised as follows; the next section provides a brief background into each of our Caribbean and Latin American Country’s economy. Section 3 provides literature review, Section 4 outlines the model and data employed, Section 5 provides analysis of the impulse response and variance decomposition, while Section 6 concludes and provides policy recommendations.

2. Country Profiles

As global commodity prices remain low and China’s economy loses momentum, economic growth among Caribbean and Latin American countries continues to be anemic in a stressed global economic environment. The IMF has reduced its growth projections for the region, forecasting an average growth of 0.5% in 2016. This would be the second year consecutive negative average output after materializing negative growth in 2015. Even though the forecasted average growth rate is negative, some countries have been doing better than others, and the IMF has recommended that in order for these countries to improve their growth potential, they should improve the management of transitional phases and take measures to address their structural weaknesses3.

To fully put into perspective the impact of temporary and permanent shocks on the current and account and the exchange rate, it is important to understand the political economy of each country in the analysis. Argentina’s economy is endowed with natural resources, balance by a strong export oriented agricultural sector. However, negatively affected by recurrent home grown financial crisis, capital flight and high public debt, Argentina’s real GDP growth has averaged close to 2 percent over the last couple of years, 6 percent below the pre 2008 average. Unemployment is currently 7.7% and gross national savings 17% of GDP. Inflation is consistently high and the country has constant fiscal and current account deficit; see Figure 2 and Figure 3.

Bolivia is one of the least developed countries in Latin America, though endowed with natural resources and has maintained a strong natural gas export sector. Recovering from political and racial instability prior to the Global Financial Crisis, average annual GDP growth rate is currently 6%. The country has low stable inflation and Unemployment 7.4%. Benefiting from high commodity prices after 2010, Bolivia has large trade surplus and gross national savings averaged more than 24% of GDP over the last few years.

Foreign trade forms a large portion of Chile’s exports-approximately 1/3 of GDP. GDP growth recovered quickly from the financial crisis of 2009 and had average roughly

![]()

Figure 3. Argentina’s impulse response function.

4 percent per annum since. They have fairly good monetary and fiscal policy. Over the last decade, Chile has accumulated surpluses in sovereign wealth funds of more than 20 billion dollars, different from their net international reserves held by the central bank. Chile signed the OECD convention in 2010 becoming the first Central American country to become a part of the OECD. National savings average 20.8 percent of GDP per annum and unemployment about 6 percent per annum. See Figure 2 for Chile’s current account to GDP ratio.

Sound economic policies including those direct towards free trade has helped Columbia maintain an average real GDP growth rate of more than 4.5% over the last couple of years. With an improved rating on government debt instruments Columbia has been able to attract record amounts of foreign direct investment in 2013 and 2014. Columbia has a strong energy and mining based export sector; the fourth largest coal exporter in the world and the fourth largest oil producer in Latin America. Gross national savings average 21% over the past few years and the unemployment rate is little over 9%.

GDP growth in Costa Rica has also averaged close to 4 percent post global financial crisis of 2008. Costa Rica’s current account to GDP ratio fell sharply by more than 16% during the Global financial Crisis of 2008 but recovered quickly, increasing by about 12 percent in 2009. The country has one of the highest levels of foreign investment and the highest level of foreign direct investment per capita in Latin America. They have high education levels and are fairly politically stable. Costa Rica moved into the production of high value-added goods such as microchips. National savings is about 16.3 percent of GDP and unemployment 17.9 percent. This is higher than the other countries in the region.

Jamaica’s debt to GDP ratio is almost 140%. The recent Extended Fund Facility offered by the IMF helps to provide support for their budget and NIR. Limited fiscal space has resulted in poor infrastructural development and capital expansion. Gross national savings of 10.8 percent is low per annum and the unemployment rate of 16.3 percent is high. Recommendations here imply that Jamaica can improve its current account situation and the competitiveness of its goods in the international market place by facilitating a depreciation of the exchange rate relative to the bench mark US dollar.

Jamaica’s high propensity for consuming foreign goods and services with little to supply to the rest of the world has resulted in a continuous negative current account balances. Based on the Mundell-Fleming model; government policy directed at correcting such weak current account position should allow the exchange rate to depreciate to increase a country’s competitiveness. In so doing, the country’s exports will appear cheaper to foreigners and imports appear more expensive to domestic citizens. The increase in external prices should reduce the country’s demand for foreign currency given that the demand for goods with higher prices will fall, while at the same time exports should increase as Jamaica’s goods and services are cheaper to the rest of the world. This should gradually eliminate any discrepancy between a country’s imports and exports, narrowing the current account deficit.

This approach can only be successful if a country has inelastic demand for imports (oil etc), if the country has high volume of imported inputs in its production process, or if a country has high volume of debt denominated in foreign currency; Saibene and Sicouri [8] and Van Wijnbergen [9] . Krugman and Taylor [10] also found evidence to suggest that devaluation might have negative effect on output growth. The final price of domestic goods is a function of the exchange rate depreciation. Given that the country has a high proportion of imported inputs with little value added, the cost of the finished goods increase as the exchange rate depreciates thereby mitigating any favorable price advantage it might have received from currency depreciation.

Mexico’s current account to GDP ratio displays a meandering trend over the last decade; falling to its lowest point in the Global Financial Crisis similar to other countries. GDP growth rate fell to −0.4 percent during this time as well. Their economy bounced back quickly and GDP growth has averaged more than one percent since. Mexico has gradually been balancing their service economy with manufacturing. National savings is 21 percent of GDP and the unemployment rate 4.9 percent. The next section provides a review of the literature on current account and exchange rate dynamics.

Paraguay’s economy has a large informal sector consisting of re-export of consumer goods and a contingent of micro-entrepreneurs and street vending in the urban areas. This balanced by subsistence agriculture farming in the rural areas has helped to maintain unemployment just below 8% on average. Strong stimulus fiscal and monetary policies in recent years boosted GDP growth from little over 4% in 2012 to more than 13% in 2013, the economy reverted to negative growth since and is gradually recovering. Gross national savings is roughly 15% and the country maintains a relatively stable current account to GDP deficit.

Peru is the world’s second largest producer of silver and the world’s third largest producer of copper. Fetching high international prices for these metals, Peru’s GDP growth rate averaged little over 5% percent 2010 to 2014 years increasing from a low of 1% during 2009 after the Global Financial Crisis. Growth has slowed since due to weaker global commodity prices. The Peruvian economy has stable interest rates, exchange rates and inflation is maintained within a minimum bound of 1 to 3 percent. Gross national savings has averaged more than 23% of GDP and the unemployment rate is little over 7 percent. A review of the literature on the impact of temporary and permanent shocks on the current account and real exchange rates follows in the next section.

3. Literature Review

The literature proposes several different methods of analyzing the current account and real exchange rate phenomenon. Traditionally, the analysis of current account and real exchange rate has been carried out on largely separate tangents. Edison and Pauls [11] in their assessment of the relationship between real exchange rate and real interest rate posits that real exchange rate movements relies upon either interest rate and purchasing power parity conditions, as proposed by De Gregorio and Wolf [12] and Chinn [4] .

Franklin [13] examined the issue for Jamaica using quarterly data from 1997 to 2009. The results of the paper show that permanent shocks are marginally more effective than temporary shocks in explaining exchange rate and current account movement. Unit root tests employed in Franklin [13] found the REER to be stationary while current account to GDP ratio is nonstationary, contrary to the existing literature where the REER is nonstationary and the current account to GDP ratio is stationary. In such a case it is quite easy to misinterpret the VAR output and the shocks correspondingly. Our research is in keeping with the existing literature as we find the REER to be nonstationary and the current account to GDP stationary in the case of Jamaica. By so doing we can better identify and distinguish permanent shocks to productivity and temporary monetary shocks. This will facilitate comparisons with the results of Lee and Chinn [1] for the G7 countries without loss of generality or misunderstanding of the shocks to be identified from the model.

Several studies [1] [3] ; Affandi and Mochtar [6] decompose the current account and the real exchange rate into temporary and permanent shocks and argue that a temporary shock creates the combination of a current account surplus (deficit) and real exchange rate depreciation (appreciation). According to Affandi and Mochtar [6] , permanent factors are those that structurally affect current accounts in the long run such as supply side, productivity, as well as changes in preference. They define temporary factors on the other hand, as those that account affect current account only in the short run, such as nominal variables like price, money supply, and nominal exchange rate.

Chinn and Lee [3] in their study on The Current Account and The Real Exchange Rates developed their methodology through the IS-LM model. Through this framework Chinn and Lee [3] showed that under flexible prices, the neutrality of normal shocks will hold on real exchange rate in the long run. Consequently, contribution of nominal shocks in explaining current account is abolished in the long run. On the other hand according to Affandi and Mochtar [6] , in the short run where the price is not flexible, their results show that money supply increases will depreciate the currency and increases in nominal shocks will revamp the current account.

Lee and Chinn [1] make two assumptions in their analysis. First they assume that temporary shocks have no long run effect on the real exchange rate. This assumption is consistent not only with earlier intertemporal models (such as Obstfeld and Rogoff [2] who hold real exchange rate constant in their model using the assumption of purchasing power parity of the current account) but also with recent intertemporal models of open economy (such as Betts and Devereux and Betts [14] and Chari et al. [15] where monetary shocks induce short-run fluctuations in the real exchange rate, via the pricing-to-market effect; however, such effects dissipate in the long run). Second, they make the assumption that global shocks have no effects on either of these variables; only country-specific ones have an effect. Both assumptions made are consistent with a broad spectrum of open-macro models.

Lee and Chinn [1] examine the exchange rate and current account dynamics of the US, Canada, the UK, Japan, Germany, France, and Italy using the Structural Vector Autoregressive (VAR) method of estimation over the period 1979/1980 to 20004. For real exchange rate, they employed the CPI-deflated real exchange rate series which is a multilateral, trade-weighted index, available at the monthly or quarterly frequency. Under the minimal identifying assumptions that apply to most intertemporal open- macro models, Lee and Chinn [1] results are concurrent with the literature. From their analysis they found that, with the exception of the US, temporary shocks play a larger role in explaining the variation in the current account, while permanent shocks play a larger role in explaining the variation in the real exchange rate.

They also found that temporary shocks depreciate the real exchange rate and improve the current account balance. Permanent shocks appreciate the real exchange rate, and in some countries, improve the current account balance in contradiction to many extant models (with the exception of the UK). Lee and Chinn [1] went on to further state that while their results lend support to two-sector models, the empirical and theoretical analysis of this approach is left for future research.

Shibamoto and Kitano [5] in their analysis of structural change in current account and real exchange rate dynamics in the G7 countries extend the framework of previous literature that isolate temporary and permanent shock by examining a possible structural break in current account and real exchange rate dynamics. Their research covers the period 1980?2007. From their analysis they found structural changes in two-vari- able dynamics for all G7 countries during the 1990s. Their results showed that temporary shocks have not been the main source of fluctuation in the current account

since the 1990s and imply that the conventional mechanism has played a limited role in explaining the dynamics of the two variables.

Affandi and Mochtar [6] investigated the relationship between structural changes in Indonesia and shifts in current account patterns in the periods before and after the Asian crisis. They adopted the approach of Lee and Chinn [1] [3] that was based on the framework of Clarida and Gali [16] with two variables namely the current account and the real exchange rate that are approximated by permanent and temporary variables. Shocks at each variable were classified as real and nominal shocks respectively.

Affandi and Mochtar [6] estimated a bivariate VAR of real exchange rate and ratio of current account to GDP by imposing long run Blanchard?Quah [7] restrictions to distinguish nominal and real shocks. They estimated the relationship using data from 1990: 01 to 2012:02 capturing the impact of structural changes by first empirically testing sample from 1990 to 2012 after which they divided the sample into two sub samples covering pre 2000 (1990-1999) and post 2000 (2000-2012). This was similar to the approach of Shibamoto and Kitano [5] . Their results were concurrent with the those of Lee and Chinn [1] [3] and Chinn et al. [17] showing that permanent shocks (as a reflection of real or productivity shocks) create current account surplus coupled with real exchange rate improvements. On the other hand decreases in productivity will suppress the current account and deteriorate the real exchange rate. Affandi and Mochtar [6] also found that temporary shocks (as reflected by nominal shocks) drive the current account surplus while concurrently worsening the real exchange rate.

4. Empirical Analysis

To analyze current account and exchange rate dynamics in the selected Caribbean and Latin American Countries; Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Columbia, Costa Rica, Mexico, Paraguay and Peru, we employ a bivariate Vector Autoregressive model proposed by Lee and Chinn [1] , who analyzed the same for the G7 countries.

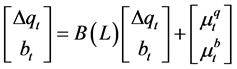

Consider the following:

(1)

(1)

where  is the first difference of the real effective exchange rate and

is the first difference of the real effective exchange rate and  is the current account to GDP ratio and

is the current account to GDP ratio and

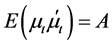

(2)

(2)

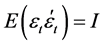

is the vector of exchange rate and current account innovations. With

,

,  and

and

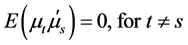

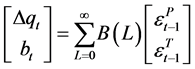

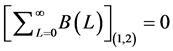

The VAR can be represented by the following moving average process,

(3)

(3)

where  is a vector of permanent and temporary shocks respectively, the moving average representation of the model is given by

is a vector of permanent and temporary shocks respectively, the moving average representation of the model is given by

with ,

,  and

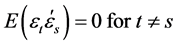

and  we impose the Blanchard and Quah [7] restriction that temporary shocks do not have a long run effect on the real exchange rate such that

we impose the Blanchard and Quah [7] restriction that temporary shocks do not have a long run effect on the real exchange rate such that

(4)

(4)

The MA representation can be written as

(5)

(5)

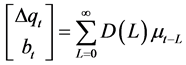

Given that the variance covariance matrix

![]() (6)

(6)

Using the fact that ![]() Equation (3) above can be re-written as

Equation (3) above can be re-written as

![]() (7)

(7)

Such that

![]() (8)

(8)

Equations (4) and (5) allows us to find the matrix ![]() such that from the permanent and temporary shocks can be identified where

such that from the permanent and temporary shocks can be identified where

![]() (9)

(9)

The stochastic component of the real effective exchange rate and the current account variables is decomposed into temporary and permanent shocks. The impact of temporary shocks is attributed only to temporary variables and that of permanent shocks is attributed only to permanent variables. The permanent current account movements are attributed to structural factors, while the permanent impact on the exchange rate is attributed to structural factors that can impact the exchange rate. The next section outlines and summarizes the data employed. All analysis for this research is done in E- views 9.

Data

Quarterly data from 2005:Q1 to 2014:Q3 on the real effective exchange rate, GDP, and the current account balance are collected from the IMF International Financial Statistics IFS for Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Columbia, Costa Rica, Jamaica, Mexico, Paraguay and Peru. Current account originally denominated in USD has been converted to local currency for all ten countries using the USD exchange rate for each respective quarter. Similar to Lee and Chinn [1] we create a variable which expresses the current account as a percentage of GDP for each country respectively. Summary Statistics are provided in Table 1, while the summary statistics for the REER is given in Table 2.

The Augmented Dickey Fuller [18] unit root test and the Phillips Perron [19] unit root test are employed to examine the stationarity properties of our variables, which is a necessary condition to ensure that the MA representation of our model converges. For each country, the null of a unit root for the REER in levels could not be rejected. The

![]()

Table 1. Summary statisticsfor the current account to gdp ratios.

![]()

Table 2. Summary statisticsfor the real effective exchange rate (REER).

results of the unit root tests indicate that the REER is difference stationary while the current account to GDP ratio is stationary in levels for 9 out the 10 countries in the study. The null hypothesis of a unit root is rejected for every country except Brazil, see Table 3. For the most part, the stationarity properties of our data are similar to those of the G7 countries analyzed by Lee and Chinn [1] . Diagnostic tests indicate no autocorrelation and heteroskedasticity among the variables in the model.

5. Empirical Analysis Country Profiles

5.1. VAR Analysis

Ascertaining the roots of each variable for each country has enabled the decomposition of shocks into temporary and permanent. The results indicate that REER and current account to GDP balance in each country respond differently to temporary and permanent shocks. The REER appreciates in Argentina, Bolivia, Columbia, Costa Rica, Jamaica, Mexico, Paraguay and Peru depreciating only in Chile in response to a one standard deviation temporary monetary shock. The current account to GDP ratio improves in Argentina, Columbia, Jamaica, Mexico and Peru, while worsening in Bolivia, Chile, Costa Rica, Paraguay, in response to a one standard deviation temporary monetary shock.

The REER appreciates in Argentina, Chile, Columbia, Jamaica, Mexico, Paraguay and Peru, while depreciating only in Bolivia and Costa Rica in response to a one unit standard deviation permanent productivity shock. The current account to GDP worsens in Argentina, Chile, Columbia, Costa Rica, Jamaica, Mexico, Paraguay and Peru, improving only in Bolivia in response to a one unit standard deviation permanent productivity shock.

In more detail, Argentina’s REER appreciates in the first two periods after which the effect disappears to zero in response to a one standard deviation temporary monetary shock. The current account balance improves slightly in the first period meandering to

a. ADF is the Augmented Dickey Fuller unit root test and PP Phillips Perron unit root test

zero afterwards. The exchange rate shows great appreciation in response to a permanent productivity shock, in this case the current account worsens in the first period, improving in the second the effect gradually disappears This result is congruent with prediction of single sector open economy models. Including the theoretical motivation presented in Lee and Chinn [1] , where an appreciation of the real exchange rate reduces a country’s relative price competitiveness as a result the current account balance worsens, see Figure 3.

Bolivia’s REER is unresponsive to a temporary monetary shock, displaying marginal appreciation, nevertheless the current account worsens in the first two periods, improving in the third, after which the effect disappears to zero. The exchange rate depreciates in response to a permanent productivity shock in the first period, the effect gradually disappears. The current account balance improves slightly in the first period meandering to zero afterwards in response to a permanent productivity shock, see Figure 4. The results for Bolivia, along with Argentina are congruent with prediction of single sector open economy models. Including the theoretical motivation presented in Lee and Chinn [1] , where an appreciation of the currency reduces a country’s relative price competitiveness as a result the current account balance worsens.

Chile’s REER is irresponsive in the first period but appreciates in the second and third periods in response to a temporary monetary shock. The current account to GDP ratio worsens as a result in the first two periods, improving in third period, after which the effect disappears to zero. The exchange rate appreciates significantly in response to a permanent productivity shock, in the first two periods, no effect thereafter, the current account is irresponsive in the first period, declining in the second and improving in the third, in response to a permanent productivity shock, see Figure 5.

Columbia’s REER appreciates in the first period in response to a temporary monetary shock, while the results pose a puzzle, where an appreciation of the exchange rate is associated with the current account improvement slightly overtime, Figure 6. This re-

![]()

Figure 4. Bolivia’s impulse response function.

![]()

Figure 5. Chile’s impulse response function.

sult coincides with the findings of Saibene and Sicouri [8] , Van Wijnbergen [9] , and Krugman and Taylor [10] . As it relates to a one unit standard deviation permanent productivity shock, the exchange rate appreciates significantly after the first two pe-

![]()

![]()

Figure 6. Columbia’s impulse response function.

riods as the effect gradually tapers off to zero. The exchange rate appreciation is associated with a decline in the current account balance in response to a permanent productivity shock in the first two periods, the effect gradually disappears. Congruent with prediction of single sector open economy models and the theoretical motivation presented in Lee and Chinn [1] , once more.

Costa Rica’s REER appreciates in the first two periods in response to a temporary monetary shock. As a result, the current account worsens in the first three periods, improving in the fourth, after which the effect disappears to zero. As it relates to a one unit standard permanent productivity shock, the exchange rate depreciates in the first two periods and is associated with a fall in the current account balance in response to a permanent productivity shock in the first period, which pose a puzzle again, the effect gradually disappears, see Figure 7. The results here once more coincide with the results of Saibene and Sicouri [8] , Van Wijnbergen [9] , and Krugman and Taylor [10] .

For Jamaica, the real exchange rate immediately appreciates in the first two quarters after which it depreciates and the effect gradually disappears in response to a temporary one standard deviation monetary shock, see Figure 8. The puzzle exists here as well, where the current account improves marginally as the exchange rate appreciates congruent with the results of Saibene and Sicouri [8] , Van Wijnbergen [9] , and Krugman and Taylor [10] , the effect quickly fades. The real exchange rate for Jamaica appreciates immediately in response to a one standard deviation standardized permanent productivity shock, while the current account slightly worsens initially as the effects disappears to zero after the first three quarters. This result is congruent with prediction of single sector open economy models. Including the theoretical motivation presented in Lee and Chinn [1] as well.

![]()

Figure 7. Costa’s impulse response function.

![]()

Figure 8. Jamaica’s impulse response function.

For Mexico, the real exchange rate immediately appreciates in the first two quarters after which it depreciates and the effect gradually disappears to zero in response to a temporary one standard deviation temporary monetary shock, Figure 9. The current

![]()

Figure 9. Mexico’s impulse response function.

account improves gradually as a result. The result is supported by Saibene and Sicouri [8] , Van Wijnbergen [9] , and Krugman and Taylor [10] . The real exchange rate for Mexico appreciates immediately in response to a one standard deviation permanent productivity shock, while the current account slightly worsens initially as the effects disappears to zero after the first three quarters. Congruent with prediction of single sector open economy models, and the theoretical motivation presented in Lee and Chinn [1] as well.

The real exchange rate for Paraguay immediately appreciates in response to a one standard deviation permanent productivity shock in the first two periods, while the current account worsens initially and improves after the first two quarters as the effects disappears to zero, see Figure 10. As it relates to a permanent productivity shock, the REER appreciates in the first two quarters depreciating in the third and the effect disappears to zero. As the exchange rate depreciates (appreciates) the current account balance worsens (improves). The results congruent with prediction of single sector open economy models

For Peru, the real exchange rate immediately appreciates in the first period after which it depreciates and the effect gradually disappears to zero in response to a temporary one standard deviation monetary shock. As a result, the current account improves gradually to zero over a couple of periods. This result is also supported by the results of Saibene and Sicouri [8] , Van Wijnbergen [9] , and Krugman and Taylor [10] . The real exchange rate for Peru appreciates immediately in response to a one standard deviation permanent productivity shock, while the current account slightly worsens initially as the effects disappears to zero after the first three quarters, see Figure 11. The results

![]()

Figure 10. Paraguay’s impulse response function.

here are Congruent with prediction of single sector open economy models, and the theoretical motivation presented in Lee and Chinn [1] as well. A summary of the findings is provided in Table 4.

![]()

Table 4. Summary of responses to temporary and permanent shocks.

5.2. Variance Decomposition

Variation in the results for the impulse response functions are not uncommon to exchange rate and current account analyses and pose no threat to robustness. Of equal or greater importance is to verify the existence of any empirical evidence to support the theory postulated by open economic models; where temporary shocks play a larger role in explaining current account movements, while permanent shocks play a larger role in explaining exchange rate movements. Variance decomposition for the REER and current account to GDP ratio in the sample of Caribbean and Latin America countries is provided in Figures 12-20.

As expected permanent productivity shock play a bigger role in explaining variation in the REER for all of the countries in the sample; Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Costa Rica, Jamaica and Mexico, Paraguay and Peru. Similar to the results found in Lee and Chinn [1] for most of the countries in the G7. In Argentina, more than 95% of the variation in the REER is as a result of permanent productivity shock. In Bolivia 99% of the variation in the REER is as a result permanent shocks. In Chile, more than 90 percent and in Columbia more than 95% of the variation in the REER is as a result of permanent productivity shock. More than 80 percent of the variation in the REER is due to permanent productivity shock for Costa Rica, between 76 and 82 percent in Jamaica and between 68 to 89 percent in Mexico.

As it regards the current account, temporary productivity shocks play a bigger role in explaining variation in the current account for Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Columbia, Costa Rica, Jamaica and Mexico, Paraguay and Peru. Temporary monetary shocks account for more than 97 percent of the variation in the current account for Chile. More than 90 percent of the variation in the current account is due to temporary monetary shock in Bolivia, Columbia and Costa Rica. 99 percent of the variation in the current account for is as a result of temporary monetary shock in Jamaica. 65 to 75 percent of the variation in the current account is due to temporary monetary shock in Mexico. More than 90 percent of the variation of the current account in Paraguay and more

![]()

Figure 12. Argentina’s varinace decomposition.

![]()

Figure 13. Bolivia’s impulse response function.

![]()

Figure 14. Chile’s impulse response function.

![]()

Figure 15. Columbia’s impulse response function.

![]()

Figure 16. Costa Rica’s impulse response function.

![]()

Figure 17. Jamaica’s impulse response function.

![]()

Figure 18. Mexico ’s impulse response function.

![]()

Figure 19. Paraguay’s impulse response function.

![]()

Figure 20. Bolivia’s impulse response function.

than 80 percent in Peru are as a result of temporary monetary shocks. The results here are broadly consistent with that of the G7 countries found in of Lee and Chinn [1] and the sticky price model of Obstfeld and Rogoff [2] . Permanent shocks to productivity have little effect on current account and a real long term effect the exchange rate, while monetary shocks have a greater effect on the current account in the short run, but no effect in the long run. The only exceptions are US in Lee and Chinn [1] . Lee and Chinn [1] postulate that, the greater impact of a permanent productivity shock in the US economy may be due to a substantial swing in the US foreign currency policy relative to other G7 countries. There is no evidence to suggest that exchange rate overshooting has been occurring from the effects of a temporary monetary shock.

6. Conclusions

This paper analyses the impact of temporary monetary shocks and permanent productivity shocks on the real effective exchange rate (REER) and the current account in selected Caribbean and Latin American countries; Jamaica, Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Costa Rica, Mexico, Paraguay and Peru using quarterly data from 2005Q1 to 2014Q4. The results show that permanent shocks interpreted as a positive shock to productivity improve the REER and worsens the current account for Jamaica, Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Mexico, Paraguay and Peru. The opposite is observed for Bolivia where a permanent productivity shock improves the current account through a depreciation of the REER. While for Costa Rica, a permanent productivity depreciated the REER and worsens the Current Account. This result, outside of Costa Rica is congruent with prediction of single sector open economy models, including the theoretical motivation presented in Lee and Chinn [1] , where an appreciation of the real exchange rate reduces a country’s relative price competitiveness, as a result, the current account balance worsens and vice versa.

A temporary shock interpreted as shock to nominal variables including prices improves the REER in all the countries examined. The response of the current account is however different across countries. An appreciation of the REER improves the current account in Argentina, Columbia, Jamaica, Mexico and Peru but worsens the current account balance in Bolivia, Chile, Costa Rica and Paraguay. These results infer that different economies respond differently to temporary shocks which must be taken into consideration whenever policy is being prescribed. This supports the IMF’s view that each county should address their structural issues and better manage how they transition.

The findings further indicate that permanent productivity shocks play a bigger role in explaining variations in the real exchange rate and temporary monetary shocks play a bigger role in explaining variation in the current account to GDP ratio for all countries Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Costa Rica, Columbia, Jamaica, Mexico, Peru and Paraguay.

Our results, overall are consistent with the results of Lee and Chinn [1] except the US and the sticky price model of Obstfeld and Rogoff [2] , where permanent shocks to productivity have little effect on current account and a real long term effect on the exchange rate, while monetary shocks have great effect on the current account in the short run, but no effect in the long run. Lee and Chinn [1] postulate that, the greater impact of a permanent productivity shock in the US economy may be due to a substantial swing in the US foreign currency policy relative to other G7 countries. The stronger impact of temporary shocks on the current account in the Caribbean and Latin American Countries might be as a result of nominal price movements that alter the relative price structure between countries. There is no evidence of exchange rate overshooting.

NOTES

![]()

1Jamaica, Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Columbia, Costa Rica, Mexico, Paraguay and Peru.

![]()

2The full identification strategy is outlined here.

![]()

3https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2015/09/28/04/53/socar042716a

![]()

4This was because real exchange rate data are only available for the period after 1979 or 1980.