Estimating the impact of antenatal care visits on institutional delivery in India: A propensity score matching analysis ()

1. INTRODUCTION

Despite an increase in budget collocation for health during the past decade, India is unlikely to reach the health related 2015 Millennium Development Goals (MDG) (MDG 2010). The pace of decline is considerably slower than what would be required to meet India’s MDG target of reducing the maternal mortality ratio (MMR) 109 per 100,000 live births and the infant mortality rate (IMR) to 27 per 1000 live births.

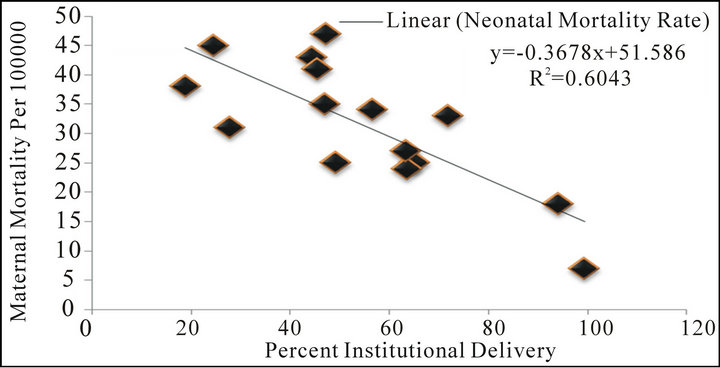

As a result of the continuing efforts made by the Government of India through various programs and also endeavors of other national, international and voluntary organizations, considerable progress has been made in attaining the MDG goals. The Government is still attempting to search for the best possible strategies so that improvement in maternal health could be accelerated further. One way could be to improve maternal and neonatal health by promoting institutional delivery [1,2]. Studies have documented an inverse relationship between the use of maternal health care and maternal and neonatal mortality [3-5]. The indicators of health care (institutional delivery) and health outcomes (maternal mortality ratio and infant mortality rate) substantiate a similar association in the case of India as well (Figures 1(a) and (b).

Further, given the slow decline in the risk of maternal

(a)

(a) (b)

(b)

Figure 1. (a) Association between percent institutional delivery (DLHS-III) and maternal mortality ratio across 15 major states, India (Office of the Registrar General, 2009). A. X axis = institutional delivery (%). Y axis = maternal mortality ratio (MMR) per 100000 live births; (b) Association between percent institutional delivery (DLHS-III) and neonatal mortality rate across 15 major states, India (Office of Registrar General and Census Commissioner, India, 2011). A. X axis = institutional delivery (%). Y axis = neonatal mortality rate per 1000.

and child death in India, it is necessary to develop an understanding of the influencing factors associated with the utilization of process indicators like institutional delivery. Though there have been some improvements in the maternal and child health indicators, the pace of rise of the institutional delivery in India has been slower than for the rest of other maternal and child health indicators [6]. The National Family Health Survey-III found that the coverage of institutional delivery is low at the national level and two out of five of all births took place at home [6].

The issue of socioeconomic and demographic factors and determinants of institutional delivery in a developing country like India has evoked considerable interest among researchers [6-8]. A few have tried to show that antenatal care (ANC) is an important independent factor in determining the choice of delivery place [9-14]. The extant literature review of studies has concluded that the use of antenatal care services during pregnancy serves dual functions.

First, antenatal care provides a preventive service that monitors signs of pregnancy complications, detects and treats preexisting and concurrent problems which helps pregnant women in lowering down their risk. Secondly, the ANC visits during pregnancy could be considered the entry point for women into the health care systems. Women who make ANC visits are exposed to the health facilities and there is an opportunity to encourage them to seek subsequent health care for themselves and their newborns.

According to studies, subsequent utilization of health care facilities might be increased because of learning by-doing, that is, subsequent participation in the systems may be greatly influenced by the earlier experience [15]. Further, several visits to the health centre may develop a familiarity with health care systems, increasing the likelihood that mothers will later rely on these systems for the benefit of their children. Moreover, it may be that women who participate in antenatal care programs receive counseling regarding the significance of subsequent health care utilization, such as delivery care and child immunization. It is envisaged that ANC visits would allow a woman to have frequent contact with the health systems/workers during the pregnancy, thereby enabling her to learn more about possible complications of pregnancy and the benefits that can be gained from institutional delivery.

At the national level the coverage of at least one antenatal care visit is around 76 percent and is comparatively higher than any other ANC component [6]. It could be argued that if all women who come for ANC visit would turn up for institutional delivery, maternal and infant death could be reduced considerably.

On the contrary, another argument put forward is that a mother who uses prenatal care may also utilize subsequent health care services, not because of the role of prenatal care but as a consequence of the mother’s inherent attitudes, beliefs and motivations. Many researchers demonstrate that a woman’s beliefs, about the risk and effectiveness of health care affect the likelihood that she delivers her birth in an institution [7,11,15]. Therefore, literature also negates the positive impact of ANC visit on institutional delivery. Moreover, the bias always arises in a cross sectional study because one could not observe the outcomes of interest at the same time for a woman when she visits and does not visit the health centre for ANC [16].

All the pooled evidence suggests there are substantial grounds to doubt the effectiveness of antenatal visits on subsequent institutional delivery. In promoting institutional delivery care it is essential that the positive effect of ANC visit leaves no room for doubt. However, the existing evidence we do have is not sufficient to quantifying its relative contribution to increase the chance of institutional delivery.

The relationship between ANC and subsequent utilization of institutional delivery in a cross-sectional study might not be strong enough due to the presence of selection bias. It is found that selected characteristics women may have a higher chance to visit ANC and these characteristics might affect the women’s belief and attitudes for subsequent utilization of health care services. As it is evident from Figure 2, a large proportion of women from the top two wealth quintiles, belong to urban areas, residents of southern and western regions, having higher education have visited health centre for receiving ANC.

Therefore this paper aims to examine the net impact of ANC visits on subsequent utilization of institutional delivery after removing the presence of selection bias in the recent round of cross-sectional National Family Health survey data. In particular, an attempt is made to know at what extent the net difference observed in outcome between treated and untreated groups of women could be attributed to ANC visit, given that all possible covariates are matched. Further, we also attempt to assess the sensitivity analysis of the applied procedure. Our paper contributes the present knowledge in several aspects. First, it reduces the possible selection bias with the help of related covariates. Second, rather than using the conventional regression method, we use propensity score matching method with a counterfactuals model that assesses the actual ANC visit effect on treated and untreated groups, and finally with the help of Mantel-Haenszel bounds it tells that whether the result is free from hidden bias or not.

2. DATA

Nationwide data from India’s latest National Family Health Survey-III (NFHS-III) conducted during 2005- 2006 is used for the present study (IIPS & Macro International 2007). This survey is the Indian version of the Demographic Health Survey. The main objective of the survey is to collect reliable up to date information on fertility, mortality, maternal, child health, family planning and other related indicators to provide state level estimates. The sampling method used under NFHS was multistage systematic random sampling.The survey adopted a two-stage sample design in rural areas and a three-stage

Figure 2. Mean of selected background characteristics of mother who did not visited health center for ANC, who make 1 - 2 ANC visits and who make more than two ANC visits.

sample design in urban areas (for details regarding sampling, see IIPS & ORC Macro, 2007). This survey covered a representative sample of 124,385 women in the age group of 15 - 49 years residing in 109,041 households throughout India. The units of analysis in this study are most recent births that took place during the five years period immediately preceding the survey interview.

3. MEASURES

3.1. Outcome Variable

In NFHS-III, mothers who gave birth during the five years preceding the survey were asked about the place of delivery. Information regarding place of delivery is available for all the successive births during five years preceding the survey. Births occurring in health facilities, such as public institutions, NGO trusts and private hospitals are termed ‘institutional delivery’. In this study whether the mother delivered birth in a medical institution (yes/no) is the response variable. Since NFHS-III collected information regarding ANC visits only for the most recent birth, we restrict our analysis only for last birth born during five years preceding the survey.

3.2. Treatment Variable

NFHS-III collected information on ANC visits for the most recent birth that resulted in a live birth during the five years preceding the survey. Mothers were asked about number of antenatal-care visits. In the present paper “frequency of contact with health system/workers” is defined as “number of ante natal care visits (No visit/1 - 2 visits/3 or more visits)”. The logic is that the number of times a woman visited for health centre for ANC represents the frequency of her contact to the health systems/workers. Finally, the analysis has been carried out in two separate models, in the first model ANC visits has been classified as either “1 - 2 visits” or “no visit”. In the second model we compare “three or more antenatal care visits” with “no visit”.

3.3. Matching Variables

On the basis of available literature and for the validity of assumptions, a large number of available pre-intervention characteristics have been included in the model. Matching based on large number of variables ensures a better chance that propensity score matching assumption holds true. Variables that at the same time influence both the participation decision in ANC visits and the outcome and which in turn, are unaffected by treatment have been included in the analysis. The lists of included variables are given below.

3.4. Household Characteristics

Region of residence (central, north, east, northeast, west and south), place of residence (urban and rural), religion (Hindu, Muslim and Other), caste (scheduled caste/scheduled tribe, non-scheduled caste/non-scheduled tribe) and household wealth quintiles (poorest, poorer, middle, richer and richest) variables have been included in the models.

3.5. Demographic Characteristics

Demographic characteristics measured in NFHS-III include current age of mother (in years), age square of mother for linearity (in years), experience of child loss (no and yes), sex composition of living children (no sons and no daughters, number of son greater than daughters, number of son less than daughters and equal number of sons and daughters), ever had a terminated pregnancy (no and yes) and birth interval (first birth, less than 24 months and more than 24 months).

3.6. Individual Characteristics

Respondent’s education (in years), respondent’s education square (in years), frequency of reading newspaper (not at all, less than once a week, at least once a week and almost every day), frequency of listening to radio (not at all, less than once a week, at least once a week and almost every day), frequency of watching television (not at all, less than once a week, at least once a week and almost every day), partner’s education (in years), square of partner’s education (in years), whether woman is allowed go to market, health facility and places outside the village/community (alone, with someone else only and not at all), having saving account in bank (no or yes), respondent’s and her partner’s occupation (not working, primary occupation, secondary occupation, tertiary occupation and quaternary occupation), birth status (wanted, mistimed and unwanted) variables reflect individual characteristics.

The variables which were present in the interval scale have been kept only in that form to capture the wide range of propensity scores while performing the matching. The analysis was carried out using Stata 10 [17].

4. STATISTICAL PROCEDURES

4.1. Description of Propensity Score Matching Analysis

Propensity Score Matching is an innovative class of statistical methods that is useful in evaluating the treatment effects for cross-sectional/observational/non-experimental data, when randomized clinical trials are not available.

4.2. Why Propensity Score Matching?

Basically we want to make comparisons of outcomes (in terms of place of delivery) between those women who have visited health centre 1 - 2 times or more than two times during pregnancy and those who have not. Such comparisons may be relatively straightforward when selection of women who have visited health facility is random and the selection process is not correlated with outcomes of interest. The average outcome for those who have visited a health facility is simply compared with the average outcome for those who have not visited a health facility. Because treated women (those who have visited health centre) and untreated women are expected to be statistically equivalent in all relevant characteristics with any other differences assumed to reflect chance, differences in average outcomes can be more convincingly attributed to the effects of the treatment.

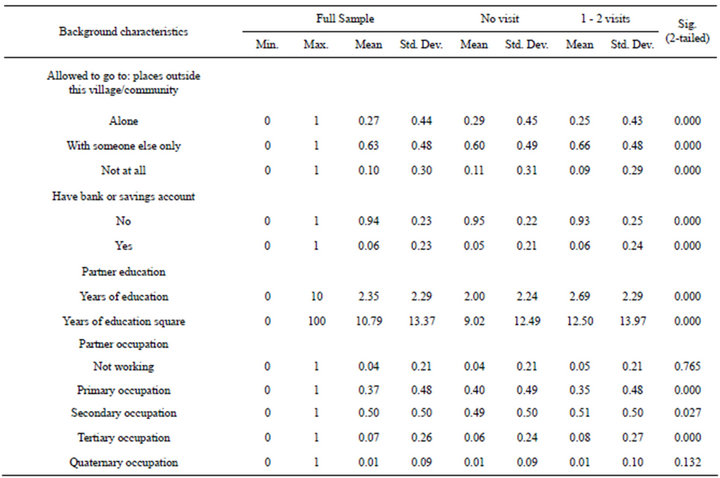

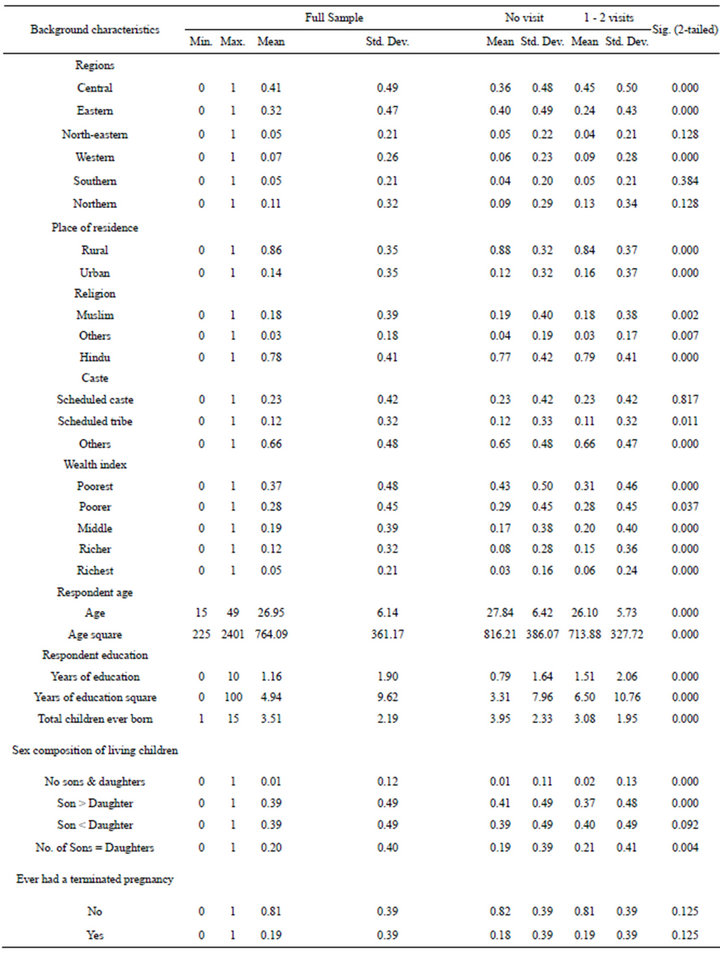

In general practice most of the time, assignment of subjects to the treatment and control groups is not random, and those who were treated may differ from those who were not, in some systematic way. It can be seen from Table 1 that the group of women who have visited 1 - 2 times or more than two times health center for ANC were different from the group of women who did not make any visit. Specifically, ANC visit is a process that permits schools to select only those women who meet certain requirements like geographical selection is a process that select out women who live in rural areas and belongs to central and eastern region where accessibility and availability of health facility is low compared to their counterparts. Also, demographic selection is a process that excludes from the treatment group those women who have higher parity (detailed descriptions of Table 1, is given in result part).

In this situation, the estimation of the effect of ANC visits may be biased by the existence of confounding factors. Finally, the question is whether the difference observed in outcome data between those who have visited health center for ANC is attributable to the ANC visits or to the fact that the women who have visited health center belong to a different population. If the differences are attributable to the ANC visits, the finding suggests that women who make ANC visits were more likely to deliver in an institution. Whereas, if the differences are attributable to the population of treatment group, the finding would show that women who make ANC visits would always have an institutional delivery, regardless of whether they have visited health center for ANC or not.

The common method for evaluating the effects of treatment concerning outcome is to estimate a singleequation multiple regression with a place of delivery outcome regressed on a measure of “frequency of contact with the health system/workers” and a set of control variables that account for all relevant observable differences between those exposed and those not exposed to

Table 1. Descriptive statistics by frequency of antenatal care visits, India, NFHS-2005-2006.

the health system/workers. The measure of treatment impact, controlling for other observable characteristics of individuals and assuming a causal interpretation, is given by the regression coefficient for the exposure variable. The conventional regression model using a dichotomous indicator of treatment does not work, and may give an inconsistent and biased estimate about the ANC visits.

An alternative solution to the multiple regression analysis, is matching methods, which compare outcomes for exposed and unexposed individuals with similar observed characteristics or similar likelihoods of being exposed [18-20]. However, the limitation of this method is that matching treatment and control individuals becomes increasingly difficult as the number of covariates on which matching is intended increases. Propensity score matching helps to overcome this limitation by allowing matching to be based on a score function of observable characteristics [21].

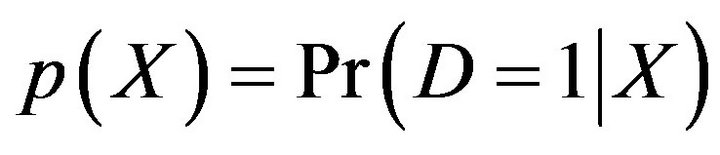

4.3. Calculation of Propensity Score

It is the probability that a woman exposed to health facility, given her various background characteristics [22]

where D = {0, 1} is the indicator of exposure to health facility and X is the multidimensional vector of pre ANC visits characteristics.

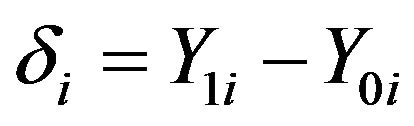

4.4. Defining the Impact of Frequency of ANC Visits

The impact of ANC visits for a woman i, noted δi, is defined as the difference between the potential outcome in the presence of and the potential outcome in the absence of ANC visits

(1)

(1)

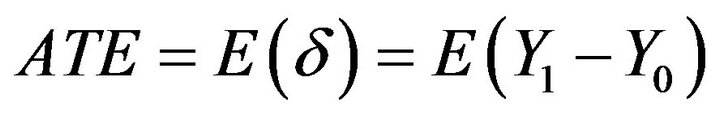

The evaluation seeks to estimate the mean impact of ANC visits, obtained by averaging the impact across all the women in the population. This parameter is known as Average Treatment Effect (ATE)

(2)

(2)

where E(.) represents the average.

4.5. Counterfactual Model

Recently the counterfactual approach which is the part of causal analysis has made important inroads into statistical and econometric work [23,24]. It has then entered sociological research through a number of papers that articulate the major differences between propensity score matching approach and the widely used standard regression approach to causal inference [25].

It is for the calculation of average treatment effect that the counterfactual model has been constructed. Counterfactual is the potential outcome, or the state of affairs that would have happened in the absence of the cause. Counterfactual model guides the estimation of ANC visits effects.

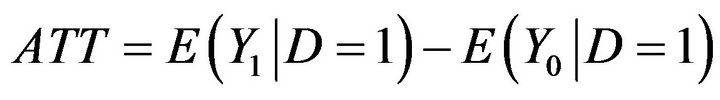

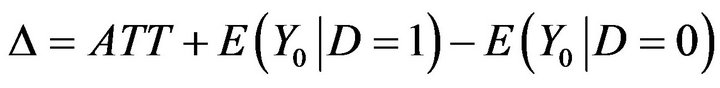

With the help of this model, Average Treatment Effect on the Treated (ATT) has been calculated. This measures the impact of the treatment on treated women

(3)

(3)

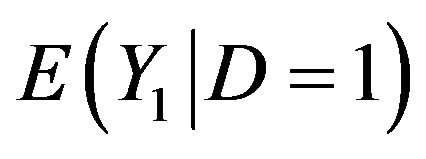

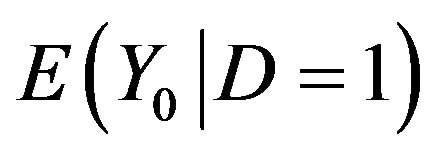

where  is the average outcome of the women who have visited a health centre.

is the average outcome of the women who have visited a health centre.

is the counterfactual, it shows average outcome that the treated individuals would have obtained in absence of ANC visits, which is unobserved.

is the counterfactual, it shows average outcome that the treated individuals would have obtained in absence of ANC visits, which is unobserved.

Finally, the Average Treatment Effect on the untreated women (ATU) has been measured, which shows the impact ANC visits would have had on those who did not make any visit

(4)

(4)

where  is the average observed outcome for those women who did not visit health centre.

is the average observed outcome for those women who did not visit health centre.

is the counterfactual and it shows the average outcome for those women who did not make any visit, if they would have obtained in presence of ANC visits, which is unobserved.

is the counterfactual and it shows the average outcome for those women who did not make any visit, if they would have obtained in presence of ANC visits, which is unobserved.

Our main aim is to calculate the average treatment effect (ATE)

We can write

(5)

(5)

If Eq.5 is true, then the ATT can be estimated by the difference between the mean observed outcomes for treated and untreated women. However, in many cases Eq.5 is not true. The main goal of an evaluation is to ensure that the selection bias is equal to 0 in order to correctly estimate the parameter of interest. Matching is the solution to overcome this problem.

4.6. Matching Correction Method

Different matching methods have been developed, all attempting to match as many treatment individuals with control individuals as possible. We have applied several matching methods and overall measures of imbalance in the covariates (before and after matching) are checked. The result shows that the average standardized bias is reduced maximum through nearest neighbor matching with replacement method. Thus, among all matching methods, we make use of the Nearest Neighbor Matching with Replacement method in the both the models i.e. “no visit” vs. “1 - 2 visits” and “no visit” vs. “at least three visits”.

4.7. Assumptions

Basically matching relies on the assumption of conditional independence of potential outcomes and treatment assignment given observables. This is the so-called Conditional Independence Assumption and is also known as “unconfoundedness” in the program evaluation literature.

4.8. Conditional Independence Assumption

For a given set of observable X which is not affected by treatment, potential outcomes are independent of treatment assignment:

(Un-confoundedness) Y(0), Y(1) ,

,

The practical meaning of this condition for matching is the availability of characteristics observed before the intervention takes place, as the variables observed after the intervention could themselves be influenced by the intervention.

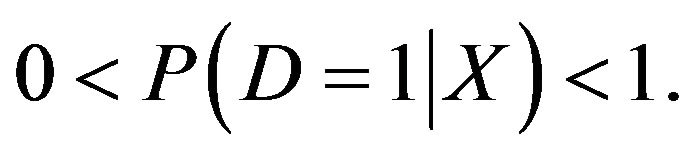

4.9. Common Support

A further requirement besides independence is the common support or overlap condition. It rules out the phenomenon of perfect predictability of D given X:

(Overlap)

It ensures that persons with the same X values have a positive probability of being both participants and nonparticipants. Treated units whose P is larger than the largest P in the non-treated pool are left unmatched.

5. RESULTS

5.1. Descriptive Statistics: Mean and Standard Deviation by Frequency of Antenatal Care Visits

Table 1 presents the unadjusted mean and standard deviation of selected socio-economic and demographic characteristics of mother who did not visited health center for ANC and those who made 1 - 2 ANC visits. The study was based on 7219 (48.6 percent) mothers who do not make any ANC visit and 7641 (51.4 percent) mothers who made 1 - 2 ANC visits for their last pregnancy.

In the absence of randomization, the group of mothers that made 1 - 2 ANC visits were substantially different from the group of mothers who did not visit health canter for ANC. It can be noted from the table that compared to their matching counterparts, mothers who did not make any ANC visit were having significantly less chance to reside in urban areas and they mainly belong to the eastern region followed by the central region, come from the poorest and poorer households and were mainly less educated.

The analysis shows that mother who did not make any ANC visit belong to Muslim religion and scheduled tribes. The data also indicates that the mean total children ever born were relatively higher for these women compared to their counterparts. Compared to their matching counterparts these women have large number of sons than daughters, more chance to report their last birth as unwanted and had experienced child loss. Women who did not make any ANC visit had less chance to get exposed to the mass media, as the table clearly shows that larger proportion of women were not in touch with news paper, radio and television. Lastly, mothers who do not make any antenatal care visit have more chance than their counterparts to be unemployed.

On the other hand, mothers who made 1 - 2 antenatal care visits were having significantly higher chance to reside in western region, belong to urban areas, being Hindus and to non-scheduled caste/tribes. The table clearly shows that they mainly come from the middle to richest class and were having less number of children ever born and have equal number of sons and daughters. Compared to their counterparts, women who had visited health facility for at least 1 - 2 times reported status of last child was wanted, had less experience of child loss and had higher chance of having exposed to mass media i.e. their frequency of reading newspaper, listening radio and watching television was significantly higher compared to women who did not make any antenatal acre visit. These women had significantly higher chance of having savings account in bank.

In the case of no visit vs. more than two visits, the study is based on 7219 (31.2 percent) mothers who did not make any antenatal care visit and 21,990 (68.8 percent) mothers who received more than two antenatal care visits for their youngest child. It can be noted (table not shown) that compared to their matching counterparts, mothers who made at least three ANC visits were having significantly higher chance to reside in urban areas and they mainly belong to southern and eastern regions come from the richer and richest households and were highly educated. The caste profile of these women closely resembled that of women who made more than two visits for ANC belonging to non Scheduled Caste/Scheduled Tribes. They have less number of children ever born and have not had any child loss. Their frequency of reading newspaper, listening radio and watching television was significantly higher compared to their counterparts. Husband’s of women who made more than two antenatal care visits are mainly involve in tertiary and quaternary occupations, they allowed women to go to market, health facility and outside the village/community alone compare to their counterparts.

The finding reveals that socioeconomic and demographic characteristics of women who make 1 - 2 or more than two ANC visits were significantly different from those who did not make any ANC visit during pregnancy. Also it clearly shows that selection bias was present in the study population, which could be solved by the matching process. Multiple regressions analysis cannot address bias problem and this needs balancing of two groups in terms of all possible covariates.

5.2. Choice of Variables and Algorithm for Matching

Only those variables which show that the means difference, between treated and untreated groups were significant has been included for matching purpose. Further, “hit or miss” method has been applied to satisfy the balancing property, and finally to achieve the quality of matching, probit model has been applied.

Region of residence, place of residence, household wealth quintiles, religion, caste women age, women age square, respondent education, respondent education square, frequency of reading news paper, sex composition of living child, partner education, partner education square, whether a woman is allowed go to: place outside the village/community, having saving account in bank, previous birth interval, experience of child loss and number of children, have satisfied the balancing processes between women who had 1 - 2 visit health center for ANC and those who did not make any visit.

when women who have visited a health center more than twice for ANC and those who did not make any visit for ANC are considered, woman’s age, women age square, place of residence, household wealth quintile, respondent’s education, respondent’s education square, women’s religion, frequency of reading news paper, partner’s education, partner’s education square, caste of women, having a savings account in bank, experience of child loss, whether women is allowed go to market and health facility, respondent’s occupation and birth status have satisfied the balancing processes.

5.3. Description of the Estimated Propensity Scores

Table 2 Model A presents a description of the estimated propensity scores that is, probability of receiving 1 - 2 ANC visit vs. no ANC visit women. The mean propensity score is 0.51, with little variability (standard deviation is 0.15) between treatment and control groups.