Synthesis and Characterization of Poly(D,L-Lactide-co-Glycolide) Copolymer ()

1. Introduction

The most important components of a living cell (proteins, carbohydrates and nucleic acids) are all polymers. Nature uses polymers for construction and as part of the complicated cellular mechanisms [1]. Polymers are a very versatile class of materials and have been changing our daily lives for decades [2] with important applications in the areas of medicine [3,4], agriculture [5,6], and engineering [7].

There has been a rapid growth in the medical use of polymeric materials in many fields including tissue engineering, implant of medical devices and artificial organs, prostheses, ophthalmology, dentistry, and bone repair [8-11].

The polyesters poly(lactic acid) (PLA) and poly(glycolic acid) (PGA) were the two first materials to be successfully used as sutures, and these polymers have extensively been used over the past two decades [12]. These polymers have widespread pharmaceutical use. They belong to a group of polymers that carry hydrolysable groups within their [5], which are susceptible to biodegradation [13]. An interesting alternative to the use of these materials is the copolymer poly(D,L-lactide-co-glycolide) (PLGA), which contains alternate unities of lactic acid and glycolic acid monomers. The structures of PGA, PLA and PLGA are presented in Figure 1.

(a)

(a)  (b)

(b)  (c)

(c)

Figure 1. Polymers with hydrolysable chains: (a) poly(glycolic acid); (b) poly(lactic acid) and (c) poly(D,L-lactide-coglycolide) copolymer.

PLA and PLGA are relatively hydrophobic polyesters, unstable in damp conditions and biodegradable to nontoxic by-products (lactic acid, glycolic acid, carbon dioxide, and water).

The polymers derived from lactic and glycolic acids have received a great deal of attention in research on alternative biodegradable polymers. Various studies demonstrating their low toxicity, including their approval by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use as drug delivery systems (DDS) can be found in the literature [14,15]. PLGA copolymers have desirable properties, such as a constant biodegradation rate, mechanical resistance, and regular individual chain geometry [10,16,17].

The copolymerization of PLGA can basically be done in two ways: 1) Through a direct polycondensation reaction of lactic acid and glycolic acid, resulting in copolymers of low molecular weight [18,19]; 2) Through an opening polymerization of cyclic dimers of lactic acid (lactide) and glycolic acid (glycolide), resulting in copolymers with high molecular weight and therefore with better mechanical properties [20-23]. The bulk polymerization generally takes from two to six hours for temperatures around 175˚C and in the presence of initiator. Lauryl alcohol can be added during the process in order to control the molecular weight [8].

Lactide is more hydrophobic than glycolide, therefore PLGA copolymers rich in lactide are less hydrophilic and absorb less water, leading to a slower degradation of the polymer chains [10]. It is important to stress that the ratio glycolide to lactide and the physical-chemical properties of the corresponding copolymer are not linear. While PGA is highly crystalline, the crystallinity rapidly disappears in copolymers of lactide and glycolide. This morphological change leads to an increase in the rate of hydration and hydrolysis [24]. According to GILDING and REED (1979) [20], the greater reactivity of glycolide compared to lactide means that glycolide is usually found in the final polymer in a greater proportion compared to its portion in the initial mixture of monomers.

The mechanical properties, the capacity for hydrolysis and the degradation velocity of these polymers may be all influenced by the molecular mass and the degree of crystallinity [25,26]. The degradation period of biodegradable polymers is most significantly affected by: the chemical structure and composition of the system; the molecular mass distribution of the polymers; the presence of monomers and oligomers; the size and shape of the system surface; the morphology of the system components and the hydrolysis mechanism [27].

Lactide has asymmetric carbons, which means that the levorotatory (L-PLA), dextrorotatory (D-PLA) and racemic (D,L-PLA) polymeric forms may be obtained. The levorotatory and dextrorotatory forms are semi-crystalline, while the racemic form is amorphous due to the irregularities in the polymer chain [28]. The use of (D,LPLA) is preferred in a DDS system, as the drug can be more homogeneously distributed through the polymer matrix [29]. When polymers are produced for medical applications, two tin salts, tin (II) chloride and tin (II) 2- ethylhexanoate, abbreviated to Stannous Octoate [Sn(Oct)2], may be used as polymerization catalysts [21].

The main objective of this study regards the synthesis of one of the most widely used biopolymers in the medical area, the copolymer poly(D,L-lactide-co-glycolide). New conditions suitable for its synthesis are explored. The obtained biopolymers were characterised by using a variety of analytical techniques in order to identify their chemical composition, as well as the final ratio between monomers within the polymeric structure. Analytical techniques have also been employed in order to investigate the biopolymers thermal behaviour as well as to verify the presence or absence of unreacted monomers in the final reaction mixture.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. PLGA Copolymer Synthesis

PLGA was synthesised by opening the rings of D,L-lactide and glycolide in a mass polymerization. Variables such as the proportion of the stannous octoate initiator (0.02% of the total monomer mass) and the lauryl alcohol co-initiator (0.01% of the total monomer mass) were chosen based on the study conducted by KIREMITÇIGÜMÜSDERELIOGLU and DENIZ (1999) [30]. Other process variable reference values, such as the reaction time (2h) and temperature (175˚C) were chosen according to a previous study by BENDIX (1998) [21]. The copolymerization reaction is illustrated in Figure 2 [30].

Figure 2. Chemical structure of the dimers and polymers, and the copolymerization reaction.

Monomer ratios of 70/30 and 50/50 (D,L-lactide/glycolide) have been used in the syntheses. These proportions have been chosen by considering the degradation time of these copolymers [8]. These are the most commonly used ratios in controlled drug delivery systems.

A total of eight syntheses have been performed, with four of these using the 70/30 ratio and the other four with the 50/50 ratio. The synthesis methodology has been modified in order to optimize the process. In the first two syntheses (syntheses 1 and 2) a round-bottomed flask without a stopper has been used. The reagents were added to the flask, which was immersed in a thermostatic bath (Haake/B12) and stirred during the first 10min of the synthesis. In synthesis 3 a rotary evaporator (Technical/TE-210) was employed. The only difference between this and preceding reaction was the injection of nitrogen into the reaction medium. In synthesis 4, the round-bottomed flask was replaced by vacuometer-type glass flask (Protec), allowing a high vacuum (–60 cmHg) to be applied and controlled. Mechanical stirring was used throughout the synthesis. From this synthesis onwards, nitrogen was no longer injected into the reaction medium. Hence, in the last four syntheses (syntheses 5 to 8), a glass flask with a rubber stopper was used instead of the vacuometer flask and the vacuum was achieved after all of the synthesis reagents had been added. Magnetic stirring was continued until the magnetic bar ceased to move due to the increased viscosity of the solution. Table 1 summarises the syntheses carried out. They are allocated to groups characterising the 4 different routes (group), as described above.

At the end of the syntheses, the PLGA copolymer was dissolved in anhydrous methylene chloride and precipitated in excess anhydrous methanol. The obtained material was dried at between 60˚C and 70˚C under vacuum (–60cmHg) in an oven (Vacuoterm/6030A) for a minimum of 48h to remove residual solvents. The copolymer was then ground using a ball mill (Stoneware) at 100 rpm for at least 24 h. The ground PLGA was sieved in a 24- mesh sieve.

2.2. PLGA Copolymer Characterization

2.2.1. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

The DSC equipment used, a Shimadzu model DSC-50, was programmed to first heat the samples from room temperature (±20˚C) to 120˚C at a rate of 10˚C·min–1(1st run). All PLGA samples were subjected to this first run to eliminate the material’s thermal history. An unsealed aluminium sample vessel was used with nitrogen as the carrier gas at a flow rate of 20 mL·min–1. The mass of the analysed sample varied from 5 to 10 mg. At the end of the first run, the oven was cooled with liquid nitrogen until it reached a temperature of between –20˚C and –30˚C. The equipment was then programmed for another run up to 300˚C, at a heating rate of 10˚C·min–1 for the monomers and 5˚C·min–1 for the copolymers. The second-run DSC curve was the reference for determining the glass transition temperature (Tg), phase transition temperature (Tm), and degradation temperature (Td).

2.2.2. Thermogravimetry (TG)

TG analysis was carried out to measure change in mass with increase in temperature, thermal stability, and maximum degradation temperature for the samples. The test was conducted at a heating rate of 10˚C·min–1 from room temperature (±20˚C) to 400˚C in an unsealed platinum sample vessel under nitrogen atmosphere with a flow rate of 20 mL·min–1. The equipment used was a Shimadzu model TGA-50. The mass of the analysed samples varied between 5 and 10mg. This technique allowed us to determine the temperature at which thermal degradation commenced (Tonset) and the change in mass as a function of temperature increase. Derived thermogravimetric curves (DrTG) were used to identify the maximum degradation temperature (Tdeg.max.).

2.2.3. Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR)

The infrared absorption spectra were collected at 20˚C from 4000 - 650 cm–1 for monomers and copolymers samples. The spectra were recorded on a Perkin Elmer spectrometer operating in the ATR (Attenuated Total Reflectance) mode. 4 scans have been performed for a resolution of 4 cm–1. The FTIR analyses of several samples containing mixtures of PLGA and monomers have also been carried out to investigate the presence of residual monomers in the PLGA copolymers.

2.2.4. Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR)

NMR samples have been prepared by dissolving the copolymers in CDCl3 from Aldrich containing TMS at 0.05%. 1H and 13C NMR spectra were obtained at, respectively, 400 MHz and 100 MHz. Measurements have been performed at 300 K on a Bruker AVANCE DRX 400 spectrometer equipped with a 1H-13C 5 mm dual probe. The 1H NMR spectra were used to determine the ratio of the monomers in the analysed copolymers. In some cases quantitative 13C spectra have been obtained by using inverse-gated decoupling, in order to confirm the results obtained from 1H NMR spectroscopy. TMS was used as internal reference.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Synthesis of the PLGA Copolymers

During the first two syntheses (1 and 2) it was noted that vapour formed, partially condensed on the wall of the reaction flask, and then crystallised after cooling naturally. In seeking the most favourable copolymerization conditions, rotary vapour equipment was used in synthesis 3. This also enabled nitrogen to be injected, with a vacuum pump providing suction. However, the formation of vapour became more pronounced and intense. Some of the crystals were removed for analysis to identify their composition and, consequently, to define a more appropriate synthesis route.

It is possible to conclude from DSC, TG, and FTIR analyses of the crystals obtained in synthesis 3 that they were produced from the evaporation and crystallisation of the D,L-lactide monomer. Because of this, vacuum was applied in the subsequent syntheses without injection of nitrogen, by using sealed glass flasks.

Glycolide melted during the first minutes of the reaction and occupied the lower part of the reaction flask, while the other monomer, D,L-lactide, needed more time to melt and was suspended in the molten glycolide until its complete melt. Accordingly, efficient stirring was required to avoid preferential polymerization of the glycolide or the formation of a block of copolymer, as favoured by the following conditions: the temperature, the greater reactivity of glycolide compared with D,L-lactide, and the presence of the initiator. Another important synthesis variable is the application of vacuum, since it avoids the presence of moisture—which is extremely harmful to the copolymerization process [8,31,21]—and high pressure in the system due to evaporation of D, L-lactide monomer. With the evaporation of D,L-lactide the pressure inside the reaction flask (closed system) increases, favouring its condensation back to the reaction flask.

It was noted that copolymers with a greater proportion of glycolide are less soluble, requiring a greater volume of solvent (anhydrous methylene chloride) and more time for complete dissolution.

3.2. Characterization of the Monomers and PLGA Copolymers

3.2.1. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

Figure 3 shows the DSC curves for the second heating in the thermal study of the analysed monomers. The DSC curves show how heat (mW) varies as a function of temperature. Both curves show two sharp endothermic events.

It can be seen from Figure 3 that the first thermal event on the DSC curves represents the melting of the monomers (81˚C for glycolide and 125˚C for D,L-lactide). For D,L-lactide, the second endothermic peak (at 183˚C) characterises the evaporation of this monomer, also identified in the monomer characterization conducted by JABBARI and XUEZHONG (2008) [32]. In the case of glycolide, the second peak (at 206˚C) relates to the degradation of the monomer, since glycolide does not have a boiling point.

Figures 4 and 5 give DSC curves for the synthesised copolymers, grouped in accordance with the ratio of monomers. It can be seen that the thermal behaviour of the biopolymers is very similar, which means that all of them have a glass transition phase between 31˚C and 53˚C

Figure 3. DSC curves of D,L-lactide and glycolide monomers (2nd heating). Heating rate of 10˚C·min–1 and heating to 300˚C.

Figure 4. DSC curves of PLGA 70/30 copolymers (syntheses 1, 3, 7, and 8), 2nd heating. Heating rate of 5˚C·min–1 from –25˚C to 300˚C.

Figure 5. DSC curves of PLGA 50/50 copolymers (syntheses 2, 4, 5, and 6), 2nd heating. Heating rate of 5˚C·min–1 from –25˚C to 300˚C.

and degrade above 200˚C. From these DSC curves, it is possible to see the thermal transitions related to the glass transition (change in the angle of the DSC curves to the baseline) and the degradation of the polymeric chains (endothermic peak of the DSC curves).

The absence of a melting transition phase event can also be seen from the analysis of these curves. It can be inferred that all of the analysed copolymers are amorphous, which is in agreement with the literature. PLGAs containing less than 85% glycolide are amorphous [33]. Comparing the DSC curves in Figures 4 and 5 with that of Figure 3, it can be seen that there is no indication of residual monomers in the synthesised copolymers, since no endothermic event characteristic of theses monomers melting is observed on the respective DSC curves.

The results of the DSC analyses are summarised in Table 2. This table gives the glass transition (Tg) and degradation (Td) temperatures for the PLGA copolymers. The melting (Tm), boiling and/or degradation tempera-

Table 2. Thermal properties of the monomers and copolymers obtained by DSC.

tures are given for the monomers. All of the values were determined by the equipment software. The Td and Tm values relate to the endothermic peaks of the DSC curves.

After the synthesis variables were standardised, syntheses 5 and 6 for the PLGA 50/50 and 7 and 8 for PLGA 70/30 had very good repeatability for the polymerization product. The Tg and Td values for these biopolymers, obtained from duplicate syntheses, are identical or very close. This indicates the same thermal behaviour and, therefore, similar structures and morphologies for the two biopolymers synthesised in different batches.

The degradation temperature of PLGA 70/30 (261.5˚C ± 0.5˚C; related to the syntheses 7 and 8) is lower than that of PLGA 50/50 (270˚C; related to the syntheses 5 and 6). A greater quantity of the D,L-lactide monomer in the PLGA induces a greater branching in the structure due to the presence of the methyl group, making it stereochemically less thermostable. This means that the structure of PLGA 70/30 is more susceptible to thermal degradation than that of PLGA 50/50, thus giving a lower Td. When the curves obtained in the present study (Figure 5) are compared with the DSC curves for the D,L-PLGA copolymer published by SILVA JUNIOR and collaborators (2009) [34] the same behaviour regarding the glass transition and degradation of the biopolymers is observed. The values found for these temperatures are lower than the respective values found in the literature [34], possibly due to the fact that the obtained polymers have lower molecular masses, something that was not determined experimentally. Polymers with lower molecular masses degrade more easily than those with higher molecular masses [35].

3.2.2. Thermogravimetry (TG)

Figures 6 to 8 show the thermogravimetry curves (TG or TGA) and their derivatives obtained for the D,L-lactide

Figure 6. TG and DrTG curves of glycolide and D,L-lactide monomers. Heating rate of 10˚C·min–1 from room temperature to 400˚C.

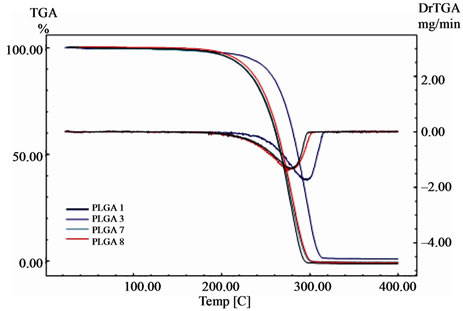

Figure 7. TG and DrTG curves of PLGA 70/30 copolymers (syntheses 1, 3, 7, and 8). Heating rate of 10˚C·min–1 from room temperature to 400˚C.

Figure 8. TG and DrTG curves of PLGA 50/50 copolymers (syntheses 2, 4, 5, and 6). Heating rate of 10˚C·min–1 from room temperature to 400˚C.

and glycolide monomers and for the synthesised copolymers. These curves show the variation of mass (%) and the derivative of the mass loss (DrTG or DrTGA) as a function of temperature (˚C). All of the TG curves presented in these figures show a single mass loss event related to the degradation process, except for the D,Llactide monomer, in which this thermal event related to its evaporation is observed.

The results from the TG analyses for the monomers and copolymers are presented in Table 3. The Tonset and Tendset values (respectively, the temperatures at which mass loss begins and ends) were obtained from the TG curves, along with the results for Tdeg.max. (temperature of maximum mass loss) for the DrTG curves of the respecttive monomers and copolymers.

The existence of only one mass loss stage for the copolymers is confirmed by the single peak observed in the DrTG curves. The copolymers fully degraded (100% mass loss), except PLGA 50/50 obtained from synthesis 4, which was 99%, and for PLGA 50/50 obtained by synthesis 2, which was 97%. This same mass loss value was observed for the degradation of the glycolide monomer. The thermogravimetry results presented above indicate that the degradation onset temperatures (Tonset) of the synthesised copolymers are higher than 240˚C.

The closeness between the respective values of Tonset and Tdeg.max. for PLGA 50/50 obtained from syntheses 5 and 6, and for PLGA 70/30 obtained from syntheses 7 and 8, also indicates the good repeatability of these methodologies. This was achieved through the standardisation of variables carried out during the copolymer synthesis stage. In addition, it can be seen that these temperatures were lower for PLGA 70/30 than for PLGA 50/50, similar to the Td values observed for these copolymers using DSC. By comparing the Tdeg.max. values

Table 3. Thermal properties of monomers and copolymers obtained by TG.

obtained from the DrTG curves of the copolymers with the Td values determined from the DSC curves (Table 2), it can be seen that they are between 261˚C and 299˚C. The Tdeg.max. values are, in general, greater than the Td values for each copolymer, which is as expected since the rate of heating in the TG tests (10˚C·min–1) was greater than that used in the DSC tests (5˚C·min–1, 2nd run).

When compared with the thermogravimetry results published by SILVA JUNIOR and co-authors (2009) [34], the polymers synthesised in this study show similar mass loss behaviour (weight loss near 100% and in a single stage), though with lower thermal degradation temperatures. It is attributed to the different molecular masses of the copolymers, as discussed earlier with regard to the DSC results.

Figure 9 shows the TG curves for all of the copolymers synthesised in this study, together with the curves for the respective monomers. These curves show that there is no residual monomer in the copolymers, since no mass loss events characteristic of theses monomers are observed. The TG curves for the copolymers show no mass loss over the temperature range in which the evaporation and degradation of D,L-lactide and glycolide occur. This observation is in agreement with the DSC curves shown in Figures 4 to 6 (see text for details).